Will Philly End Its Rape Kit Backlog?

Natasha Alexenko was a sophomore in college, majoring in film, living in New York City. She’d grown up in a small town in Ontario, raised by a single mom, and all she wanted, all her life, was to move to Manhattan, the place where she’d been born. It had a mythical appeal to her, and when she moved there in the early ’90s, it did not disappoint: she loved every inch of it, and she felt no fear. “I was going to be the next Steven Spielberg,” she says now, riding in a car with her mother after an appearance on the cable news network HLN. Back home, people worried about her, but when she found the perfect apartment with the perfect roommates — a place where she could have a dog, another dream realized — it seemed things couldn’t get much better. It was all going according to plan.

Until the day a man, a stranger, accosted her in the stairwell of her perfect apartment building, jamming the metal of a 9mm semiautomatic into her back and bending her over a railing. He raped her there, he sodomized her, then he fled. Now Natasha, dirty with his fluids, shocked, traumatized, made her way back to her apartment, where a roommate persuaded her to wait for an ambulance. All she wanted was to shower, to get rid of him. But she waited — so close to her soaps and shampoo, so close to clean clothes! — because she’d been raised to respect law enforcement, to cooperate. She wanted to help them do their job, and, well, “my body was a crime scene,” is how she puts it now.

At the hospital, she was asked many questions so they would know what part of the crime scene to investigate. She also consented to have a Sexual Assault Kit — familiarly known as a rape kit — taken. She relinquished her clothing because it was evidence. Strangers were touching her: they swabbed the inside of her mouth, her vagina, her anus. They scraped under her fingernails, and pulled and combed her pubic hair, and the hair on her head. The whole process took four hours. She just wanted a shower, but she had to spread her legs, to be penetrated. She knew it was necessary and would eventually lead to justice. She doesn’t regret it. But it was hard.

The police didn’t find her assailant. She tried to go on like everything was normal, and then her mother came with a U-Haul and said she was coming home. And that was the right thing, going home to heal, away from where it all happened. Heal partway, anyhow.

Funny thing, when she got the phone call 10 years later telling her that her rape kit had never been tested, she wasn’t even angry. The semen that coated her vagina and buttocks; the scrapings from underneath her fingernails; her own fluids; her hair; parts of her that mingled with this monster — they’d all just been sitting, forgotten, on a shelf, for a decade. During which time her assailant was free and committed other crimes, unaccountable for the way he derailed her life.

Sixteen years after the attack on Natasha, her DNA led to her attacker’s arrest and sentencing. He’ll be eligible for parole in 2057. Natasha is now head of Natasha’s Justice Project, a foundation that lobbies for the testing old rape kits, each of which represents a person like herself. It’s a woman or a man or a child with a story. And when a city has rape kits that sit on shelves, untested, it’s an affront to those people, and can have other implications for the criminal justice system. Rape kit DNA can identify unknown perpetrators or confirm known suspect; validate a victim’s narrative; link suspects to unsolved crimes; and exonerate the innocent. The information can be important to probation and parole.

Consider this:

- In Houston, testing of more than 6,000 old kits — some going back 30 years — resulted in charges filed against 29 people so far, and 850 hits in the national DNA database.

- In Memphis, a backlog of more than 12,000 untested kits, some from the 1970s, has so far yielded 459 investigations and secured 76 indictments.

- In Detroit, which is seen as the model city for clearing the backlog, testing the more than 8,500 kits has led, so far, to 10 convictions and the identification of 255 potential serial rapists. Evidence from the kits connected to crimes committed in 30 states and in Washington, D.C.

- In New York, the resolution of a 17,000-case backlog starting in the 1990s spurred more than 200 prosecutions citywide.

- In Cleveland, where there’s a backlog of almost 4,000 kits dating back to 1993, partial testing has resulted in 209 criminal indictments. Thirty-two percent of those indictments are against perpetrators identified as serial rapists.

The effort to clear rape kit backlogs has gained stunning momentum in the past couple years, in large part because of the advocacy efforts spearheaded by the Joyful Heart Foundation, which runs the End the Backlog program. Yesterday the Foundation released a statement praising the House Committee on Appropriations for its inclusion “of $41 million in funding for the Justice Department’s community-based sexual assault response initiative in their FY16 Commerce, Justice and Science funding bill.” The organization’s CEO stated: “The federal government’s investment in rape kit reform continues to send the message to survivors that they – and their experience – matter.”

•

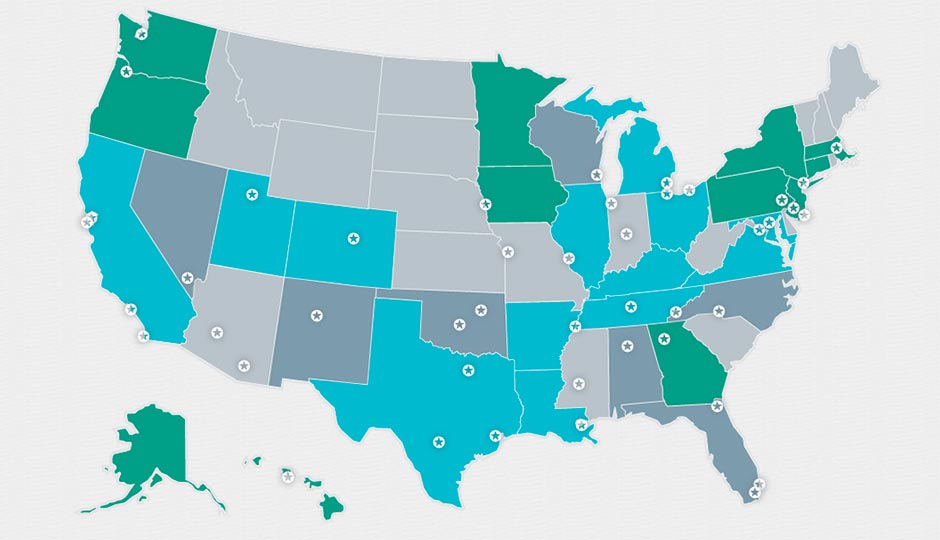

Map of backlog reform efforts via endthebacklog.org

PROGRESS HAS BEEN SPURRED in some cases by state legislation: In Colorado in 2013, for instance, a bill passed that required the testing of rape kits — and included funding to clear the state’s backlog, which numbered more than 6,000. The Joyful Heart Foundation notes:

As of May 2015, Colorado has tested more than 2,500 of its previously untested rape kits, resulting in 738 DNA profiles being uploaded to CODIS and 198 of those profiles matching convicted felons or samples from other cases. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation is prioritizing the testing of backlogged kits on which the 10-year statute of limitations has not yet expired.

Other states that have passed similar legislation are Illinois, Ohio and Texas, while Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana and Virginia have passed bills that require jurisdictions to find out how many untested kits they have.

Pennsylvania has not passed legislation of either kind. And on the municipal level, the foundation notes, “while some jurisdictions are leading the way toward comprehensive rape kit reform…many cities have not counted the untested kits in their custody.” Philadelphia does not know what size its backlog is prior to 2004, despite repeated requests from the Joyful Heart Foundation for those numbers. In fact, the Foundation’s Accountability Project, which tracks backlogs in each city and state, has had the same message on its Philadelphia page for months:

Philadelphia is one of the cities where we are using public records requests to uncover the number of untested rape kits in police storage as part of The Accountability Project. We have not yet received complete data from Philadelphia.

•

THE END THE BACKLOG movement has been met with such active, engaged reception from so many cities. Philadelphia — especially given its history on this subject — should certainly be one of them.

Overall, Philly is generally seen as a leader in its methods of handling sexual assault cases. This vaunted position is the result of a wholesale reinvention of the Philly PD’s Special Victims Unit, which was spurred by a series of Inquirer exposes in the 1990s. Due to sexism, cynicism, and a culture of blame toward victims, more than 2,000 cases between 1995 and 1997 were filed under fake codes or erroneously dismissed. After the exposes, then-Commissioner John Timoney assigned 45 detectives to reinvestigate those cases. He also put other reforms into place. According to a 2013 Guardian article about Philadelphia’s turnaround, “the police department has been transformed from one that a previous chief admitted was ‘god awful’ in its handling of sex crimes into one held up as an example to others.”

The city’s record on rape-kit testing is part of its positive reputation. In 2009, CBS News did an investigative report into untested rape kits across the country. Philly came off quite well:

Joseph Szarka, Lab Manager at Philadelphia Police Department’s Forensic Science Center tells CBS News that his department like New York City tests every rape kit, “How could we not?” he asked in a phone interview. Szarka described to CBS a series of cases where even testing acquaintance cases illuminated key evidence. Szarka says there are a few hundred kits waiting to be tested and the turnaround time is 90 to 180 days.

Yet at the end of last year, when Congress approved the $41 million appropriation, Philadelphia was mentioned in a Washington Post report as being one of a handful of cities investigated for a backlog. That kind of media coverage should have prompted a swift response. It would have been terrific to see Mayor Nutter or Commissioner Ramsey or Seth Williams stand at a podium as other cities’ officials have done and commit to ending the backlog here. But that didn’t happen.

Michael Garvey, head of the Office of Forensic Science (OFS) since 2011, says the department’s policy for testing kits has changed over the years. “The previous policy was to test every kit with an active request. All kits were submitted for analysis; however, kits may have been deactivated based on its court status,” he explained. “For example, if the District Attorney’s Office did not proceed with the court proceedings or if there was a conviction, the analysis was stopped due to resource constraints.” In 2013, Garvey updated the policy. “The current policy is that all sexual assault kits shall be tested unless it is determined that no crime has occurred and both the Philadelphia Police Special Victims Unit and District Attorney’s Office confirm this status.”

•

THE QUESTION OF ACTIVE vs. deactivated case is complicated, but important. Cases got deactivated in the past for all kinds of reasons, as Garvey conceded when we spoke in January — a judge or prosecutor felt there wasn’t enough evidence; a person took a plea or there was a conviction; it was determined that no crime was committed; the suspect was unidentified, etc. Some of those cases, Garvey says, “today we would work them without question.” And such deactivated cases may, in fact, have untested rape kits associated with them.

So OFS performed a review of cases from 2009 to the present to reactivate any kits that had been previously deactivated due to court status — about 350, Garvey says. Some of those remain untested now, as do some “new” kits from 2014. Garvey hopes to have all of the reactivated, historical kits as well as the “new” kits analyzed by June 2015. His office recently hired new forensic scientist trainees and initiated an outsourcing contract in order to make that happen.

Aside from those backlogged kits, Garvey says, all Philadelphia rape kits from 2009 to 2013 have been analyzed. “Prior to 2009, all kits that remained in active status were analyzed.”

Any case that is in the possession of the OFS for at least 30 days without a completed report of analysis, Garvey notes, is considered backlogged.

Garvey thinks Philadelphia is fairly unique in its situation in regards to the backlog. “Even prior to the electronic lab tracking, the PPD opted to analyze cases for DNA. So we’re not talking about an agency that simply shelved sexual assault evidence for years. It is expected, and was seen in our 2004 to 2014 review, that the majority of sexual assault kits were processed. It was only when the request for DNA analysis was cancelled that there was no testing.”

One advocate I spoke to said that Garvey was very knowledgable about the importance of testing. “It was a tone we don’t generally hear from law enforcement,” she said. But he is certainly wary about testing old kits, and he puts more conditions around which kits should be tested than end-the-backlog advocates do. What about the deactivated cases before 2009, for instance? What about cases going back decades?

“Rape kit testing sends a message to survivors that they — and their cases — matter,” says Sarah Haacke Byrd, Managing Director of the Joyful Heart Foundation. “It sends a message to perpetrators that they will be held accountable for their crimes. It demonstrates a commitment to survivors to do everything possible to bring healing and justice.”

Commissioner Ramsey says he and Garvey have spoken about “what is reasonable with how far back you go” when it comes to old kits. “We do have a statute of limitations of 12 years,” Ramsey notes. “I certainly think that 2000 to current is reasonable [to test] even though that extends beyond the statute.” That would afford them the opportunity to identify patterns, and see if there are any serial rapists. Ramsey says beyond 2000, they’d go in phases “and see at what point is it no longer productive simply because of the amount of time that has elapsed. These cases are very important, but if there’s no prosecution that’s possible, that weighs into it as well.” Ramsey would prioritize testing kits from so-called stranger rapes over those of known suspects, he says, though grants don’t necessarily allow for that kind of parsing.

Garvey says the retroactive testing presents many challenges for a department that is already underresourced. A continual trend of vacancies makes things difficult, he says. People come in, get trained — which takes 18 to 24 months — and then leave to work for a different city that will pay them more. There’s also the problem of space: the OFS facility simply isn’t large enough for everything they do. “We do DNA testing now even on property crimes if we think it’s probative,” he says. So testing rape kits from the 1970s? The breadth of that kind of project just seems immense — and impractical.

Given the realities of the federal database, “if the review were to go back to the 1970s, every case would need to be analyzed, if the evidence still existed. I understand that there may be a few cases that would be useful out of the thousands of cases across the country from these historic cases. However, the potential impact to current cases is being lost in this discussion.”

He says devoting resources to past cases would take away from resources for testing now.

“Analysts, lab space, instruments, and even contractor labs are limited physical resources that cannot be ignored by simply applying more funding,” he says.

•

A FEW MONTHS AGO, New York’s District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. announced a grant program of $35 million that other cities could apply to for help funding their backlog efforts. Garvey is applying for that grant, along with federal monies. Garvey says that if Philadelphia receives money from the Vance grant, the PPD would start with an inventory of pre-2004 evidence. “Once that is complete, cases would be reviewed to determine whether there is the potential for probative forensic DNA analysis,” says Garvey. “From there, a reasonable analysis plan that balances this effort with current investigations would be developed.” He notes that a careful balance must be maintained between the needs of the past and those of today.

It makes sense, but it isn’t exactly the inspiring message that other cities are sending out — and Philly could use the PR. Joe Biden, who introduced the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, spoke in March about the importance of Congress’ appropriation for rape kit testing, and specifically referred to seeing hundreds of untested rape kits on shelves in Philadelphia. Meanwhile, Detroit, Cleveland, Houston, Salt Lake City, Memphis, Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York — these are all cities that have broadcast their commitment in unambiguous ways, with words and deeds that make it clear that prosecuting sexual violence and bringing dignity to victims is an absolute priority. Even with funding as a challenge, cities have gotten creative. In The Marshall Project, Clare Sestanovich writes:

When Houston first confronted its backlog — and the attendant costs — its City Council passed a novel ordinance: a tax on local strip clubs would require venues to pay five dollars per customer toward rape-kit testing. Even more traditional establishments could incur the fee if they hosted adult activities like, say, a “naked sushi contest.”

Memphis officials estimate it’ll take approximately $6.5 million to clear that city’s massive backlog entirely, but they’ve signaled they will find the money to do it. Detroit has a large coalition of stakeholders that have raised funds, including the National Institute of Justice, the state of Michigan, the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, the Michigan Women’s Foundation and the Detroit Crime Commission. The county even hired temps to process untested evidence. In Kentucky, state Sen. Denise Harper Angel just sponsored legislation that would require an audit of untested rape kits by Nov. 1, 2015.

In Philadelphia, despite Michael Garvey’s knowledge and everyone’s good intentions, the message seems to be rather more tepid: Jeez, we’re already swamped. We don’t have time to send all that paperwork to the Joyful Heart Foundation or say we’ll do whatever we can to bring closure to victims. No one seems to know how many untested pre-2004 kits Philly even has in evidence lockers. Not knowing the number of total untested kits is not the same as being free of them.

When Natasha Alexenko hears hesitation or reluctance on the part of city officials, she finds it hard to understand. “The man who raped me was on a nationwide crime spree. He didn’t just rape, he wasn’t a specialist — he committed a variety of crimes. He was a burden on law enforcement, he created other victims. These are really bad people. They escalate in terms of their viciousness.” Clearing a backlog is not, she says, just for survivors — “that unfortunate sorority. It’s a matter of public safety.”

Joyful Heart CEO Maile M. Zambuto said yesterday: “We are so grateful to President Obama, Vice President Biden, and leaders in Congress for recognizing the urgency of this issue, and for offering leadership, resources and research to fix the problem, making the reduction and elimination of the nationwide rape kit backlog a priority.” Philadelphia should do the same.

Follow @lspikol on Twitter.