Tom Wolf: Perfect Stranger

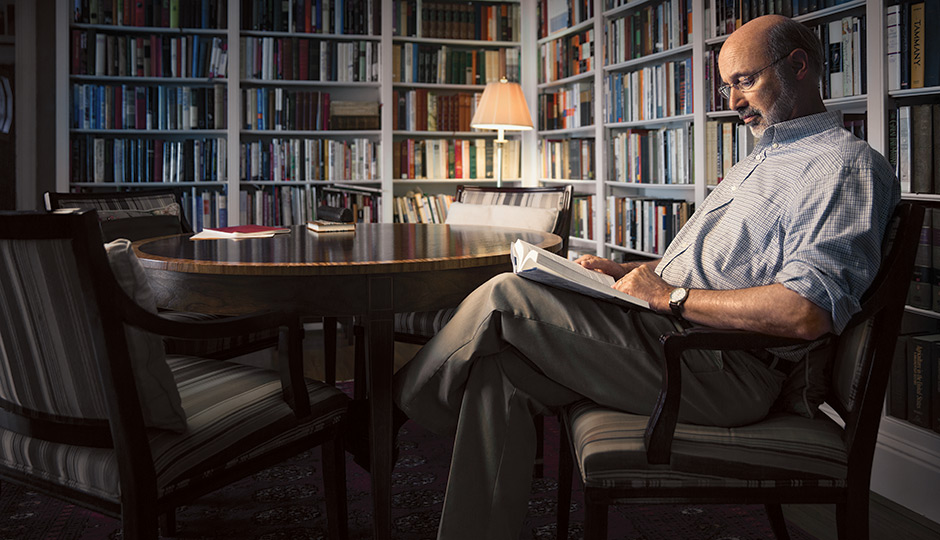

The candidate in his home in Mt. Wolf. Photograph by Colin Lenton

Wolf’s team, the Phillies, faced the St. Louis Cardinals, including Stan Musial, the player who broke Babe Ruth’s extra-base-hits record. The stadium announcer’s voice crackled through the loudspeakers, informing the crowd that anyone from Donora, Pennsylvania, Musial’s hometown, could get the slugger’s autograph when the game ended.

After the last out, Bill Wolf led his son to the visiting locker room.

“What do you think?” his father asked. “You want to go in?”

Fifty-seven years later, Tom Wolf would be the presumptive next governor of Pennsylvania. But that night, he was just an eight-year-old baseball-crazed kid standing mere feet from one of his heroes.

“No,” Tom replied. “We’re not from Donora.”

“They won’t know that,” his father said.

“No,” Tom repeated. “It wouldn’t be right.”

I hear this story from Wolf’s parents, Bill and Cornelia, at their rambling old country house in the borough of Mount Wolf, about eight miles north of York. The couple is in their 90s, dignified-old-money in every way, but the tale feels as though it hails from an even earlier time, reminiscent of apocrypha and legends like the one about George Washington and the cherry tree. There are other family fables about Honest Tom, and the Wolfs eagerly share them, delighted that their son’s virtue outdoes even their own.

The stories also echo Tom Wolf’s campaign narrative. A virtual unknown when the year began, Wolf blitzed the state with ads that declared him “not your ordinary candidate” and defined him in broadly likeable terms: South Central Pennsylvania kid. Highly educated, with a stint in the Peace Corps. Married to the same gal for 38 years. Two daughters. Started off driving a forklift in the family business, then took over, making it America’s largest supplier of kitchen cabinets.

He shared 20 to 30 percent of the profits with his employees, the ads tell us — and yes, that does sound virtuous. In 2006, he and his partners sold their majority stake in the company, and Wolf resigned and accepted a position as secretary of revenue under Governor Ed Rendell. He donated his government salary to charity and refused a state car, driving a dorky Jeep instead. He explored a run for governor in 2009, but he got a call from his old management team telling him the business he’d led for 20 years faced foreclosure. So Wolf tabled his political dream for a time and manned his old post, saving the family business and hundreds of jobs.

“I’m Tom Wolf,” he says, “and I’ll be a different kind of governor.”

The mere sight of him established the brand. Wolf dressed casually in a button-down shirt, with an open collar and sometimes an ugly yellow jacket. He even wore a beard. Veteran Pittsburgh Post-Gazette political reporter James O’Toole scanned official gubernatorial portraits till he found the last state governor with a beard: Samuel W. Pennypacker, in 1907.

The ads aired early and often, playing adroitly on the electorate’s distrust of ordinary politicians. It was a remarkably effective assault by a largely self-funded campaign that left Wolf’s better-known primary opponents in the dust before they ever truly got going.

“The race for governor used to be like a heavyweight fight,” says veteran Democratic campaign adman Neil Oxman. “This race was like an undercard. The press corps is decimated. And he had it won by March, with his ads. So of course it feels like he was never really tested.”

Wolf may not be tested this fall, either. Corbett is considered the most-likely-to-lose sitting governor in the nation, and Wolf leads him by wide margins in most polls, though that edge is eroding a bit. The result is that Pennsylvania may be led by a governor we’ve only just met, the electoral equivalent of setting up house after the first dinner date.

In truth, Wolf is much more than the folksy two-dimensional character his ads make him out to be. He is amiable, yes, but he’s also the ambitious and calculating scion of a proud and powerful family, a man who learned from an early age that he has an obligation to work for the good of the people. For most members of the Wolf clan, that’s meant fund-raising dinners and charitable works in and around York. For Tom Wolf, that hasn’t been enough. This kitchen-cabinet supplier convincingly acts the part of the nearly-extinct citizen politician, but his yearning for the most powerful job in Pennsylvania runs much deeper than mere devotion to duty.

AS HIS CAMPAIGN likes to point out, Tom Wolf lives in the same house his parents brought him home to from the hospital. The front door is framed by four white pillars and looks out on a wide yard with tightly trimmed hedges, a shaded street and a solitary train track. A couple of cargo carriers rattle past each day, on the same rail line that carried Lincoln’s funeral car. Mount Wolf — a verdant green enclave near the Susquehanna River — is named after an ancestor four generations removed. Today, the community of 1,393 is a moneyed suburb of struggling York. A century and a half ago, when the town was founded, it was a George H. Wolf who established the post office, and his brother Adam who ran the supply store — the same business that Tom Wolf would acquire, generations later, and lever into his political launching pad.

Wolf meets me, hand extended, in a deep backyard under a vine-covered trellis. Affable enough to make the ritual meeting-of-reporter feel friendly, even warm, Wolf points to a pair of old trees with winding trunks that grew tall before he was born. “My grandfather and great-grandfather planted these,” he says.

A few of Wolf’s friends had advised me to meet him here, at his ancestral home. “You just walk into that front room,” one of those friends told me, “and it’s like walking into his head. Elegant. Understated. Classical music is playing. And the whole place is filled with books.”

No classical music is playing when I arrive. But there are two comfortable couches, each set off by tall reading lamps and three long walls adorned with at least 10,000 books. “I’ve actually read these,” Wolf tells me of the entire library, and judging by the cracked spines, I believe him. “I am pretty much always reading something.” A novel might go down in an evening. Something dense, like Thomas Piketty’s 696-page economics tome Capital in the Twenty-First Century, goes more slowly. “That took about a week,” says Wolf, smiling.

Dressed in gray slacks, a light blue button-down shirt and a matching patterned tie, Wolf walks me through a shelving system grouped by subject: economics, political science, world and American history. “Look here,” he says, pointing to a particular set. I follow his finger to see that books on religion and baseball share the same column. “See?” he says. “That tells you a lot about me.”

We tend to think of self-funded candidates as cranks playing an egoistic game, like Donald Trump, or, in a best-case scenario, businessmen who perceive a vacuum of leadership, like Michael Bloomberg. Wolf belongs to a different category. He’s rich, yes, but he’s no tycoon. His $10 million contribution to his own campaign included $4.5 million acquired through a personal loan. And where Trump is a modern media creation and Bloomberg is a cutting-edge billionaire, Wolf seems to come gliding out of the past. There’s a nostalgic, old-timey quality about the man.

The week before our conclave in Mount Wolf, at an event in Center City, Wolf was meeting with a group of new immigrants. “I’m like you,” he said. “I’m applying for a job. I need you to vote, and you, all of you, will be my boss.” This was standard pabulum for any campaigning politician. But Wolf made every word sound heartfelt and earnest, like Jimmy Stewart in one of those movies where he uses all his aw-shucks integrity to save a small town.

Wolf delights in rejecting cynicism, denying, for instance, that politicians are any more resistant to compromise than anyone else. “Human beings are the same,” he says, back on Mount Wolf. “The distribution of rationality is the same in Harrisburg as it is in any other human city.”

Wolf offers this assessment with an assured, professorial air, as though inviting me to enjoy the view from atop his massive knowledge base. Beside him is his wife, Frances, who speaks in deep NPR-pitched tones and wears a flowing, brightly colored blouse. Together, sitting on one of their long reading couches and staring out benignly from behind stylish glasses, they seem like the kind of people who might overexert themselves while do-gooding.

Mindful of the family’s roots on their namesake mountain, Wolf’s great-grandparents insisted their children stay in town once they had grown. Two Wolf brothers, George and Tom, dutifully built houses on adjoining lots. A generation later, Wolf’s father, his sister and a pair of cousins moved into consecutive houses on the town’s opposite end. What the Wolfs now call, without a trace of irony, “the four families” had a total of 14 children.

The clan oozes noblesse oblige. Wolfs have served on boards and funded charities for more than a century. The William T. Wolf Center for Philanthropy, named after Tom’s father, sits about nine miles away, in downtown York. Bill Wolf actually started the profit-sharing plan featured in his son’s political ads. And each summer, Bill’s father, Earle, hosted dinners for the staff. Cars lined up carrying employees from Wolf Supply. Tom Wolf served as valet.

In Wolf’s living room, I make an observation: “When you grow up with kids whose parents are employed by your family, you must get a sense of how important the business really is.”

Wolf draws his head back, like he just heard a bum note, and gently corrects me. Those old dinner parties didn’t show him how important his family’s business was to its employees. Those dinners showed him how important those employees were to the family business, to their own families, to the community. “You see the value of what they do,” he says. “It’s not just ‘a job.’ They’re doing really important things.”

WOLF’S SENSE OF MORALITY — his acute awareness of his privileged background and the responsibilities that accompany it — seems to have developed early. As a child, he was permitted to be childish. He rode his bike, built forts in the woods, and dreamed of being a professional baseball player. But at age 12, after telling him he was going to baseball camp, his parents pulled a bait-and-switch and packed him off to a rigorous Quaker-affiliated summer camp instead. By day, Wolf learned to swim. By night, he sat under the Pennsylvania stars, discussing big ideas with distinguished camp visitors like civil rights pioneer Ralph Bunche and historical novelist James Michener. “That camp,” he says, “is where I learned that I actually had a brain.”

Wolf went on to an accomplished academic career, gathering a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth, a master’s from the University of London and, in 1981, a doctorate in political science from MIT. Along the way he traveled an important byroad, temporarily leaving Dartmouth after his first year for a stint in the Peace Corps. His assignment: Orissa, India, where the young prince of Central Pennsylvania worked in poor villages, promoting the sowing of a higher-yielding rice. “It taught me self-reliance,” he says. “I couldn’t do anything. So I had to learn.”

He learned the local language. He learned how to work with his hands, fixing farm equipment. His Peace Corps adviser, Richard Williams, remembers that Wolf lived like the natives, wearing sandals made from recycled tires, kneeling on the floor to eat. He stuck around four months beyond his two-year commitment, to see the higher-yielding crops harvested, then returned to the States more confident than ever and ready to resume his academic career.

Wolf chose MIT for his doctoral studies and began working under Jeffrey Pressman, a talented young political scientist. A little over a year later, Pressman, just 33 years old, killed himself. “It was a shattering experience,” says Wolf. He says this with an air of finality, as if he doesn’t want to delve too deeply into the tragedy. Frances adds only, “It became a more serious time.” Pressman’s death, the Wolfs seem to feel, shouldn’t be turned into some biographical benchmark for the candidate.

Wolf pondered the academic life. According to his closest friends from MIT, he could have stayed on there or taken a position at Harvard. He and Frances spent a spring afternoon strolling around Boston’s Copley Square, mulling the possibilities. They looked at the people and the buildings, the Romanesque Trinity Church. He tried to imagine a future there. But some other place still had a hold on his heart.

“I went as far as you could get from Mount Wolf and still be on the face of the Earth when I was in that village in India,” he says, “and I stayed away for a number of years. And it was this place that drew me back.”

WOLF’S RETURN TO small-town life was about more than loyalty and the tug of home. He had reasoned, for instance, that a stellar professorial career might land him a seat on the board of the Boston public library — eventually. Back at Mount Wolf, he could run the local library board within a few years. In this sense, moving back was a way of putting into practice all he had learned — a way of becoming a leader, in business and the wider community, at speed.

Wolf joined the family business, working the forklift for a while before ascending into management. In 1986, about seven years after Wolf returned, his father retired, and the company looked to the son. “There was no passing of the keys,” says his mother, Cornelia. “Tom bought it. That’s the way it always was as the company passed through the family. The new generation paid the older one.”

Wolf and his partners, cousin Bill Zimmerman and a cousin by marriage, George Hodges, took out a loan to get the deal done. All three had president titles in the new Wolf Organization. But in keeping with a tradition of low-key leadership, they planted their desks in the same open room, dubbed the Office of the Presidents: OOPS.

The Wolf Organization was essentially a sophisticated warehousing operation, capable of storing vast numbers of kitchen cabinets and building supplies till sale. Over 20 years, the company’s annual revenue grew to $385 million, and the number of employees tripled, to more than 600.

Meanwhile, Wolf made himself a force in local politics. He rallied the local business community around a cleanup of Codorus Creek. In 2006, Mike Johnson, the newly installed chair of the county Democratic Party, confessed a lack of good candidates. Wolf asked, “What process do you have in place to generate good ones?,” then helped create a pipeline for fresh political talent.

As chair of Better York, a civic organization, Wolf brought in nationally respected cities expert David Rusk to study the troubled city. Rusk concluded York faced the same sorts of problems as Philadelphia — a poor public school system, a weak tax base, generational poverty — and prescribed a turnaround plan that York continues to pursue.

Cleaning the local waterway, building a political party, advancing school reform — these are lofty pursuits for a guy selling kitchen cabinets. They also suggest that one of the most common knocks on Wolf’s candidacy — that he’s a political naïf in over his head — might be unfounded. In fact, it seems likely Wolf has long entertained the end game we’re seeing right now. “Looking back,” says Johnson, “I would expect that Tom was probably taking mental notes on all of this. Figuring out what works and thinking about how he might implement these same ideas as governor.”

Still, compared to most other gubernatorial candidates, Wolf’s political résumé is a bit thin. In the primary, that might actually have worked to his advantage. Wolf didn’t have a lengthy record to attack, and his few brushes with scandal didn’t scare voters.

In 2010, Wolf co-founded a defense fund for Steve Stetler, a former state representative who was ultimately convicted of misusing taxpayer money for campaign purposes. But within the Wolf narrative — he and Stetler were lifelong friends, youth soccer teammates — the whole affair turns into a sepia-toned tale of unflinching loyalty.

His service as the campaign chair for former York mayor Charlie Robertson looks darker. In 2001, Robertson’s reelection run was interrupted by an indictment in the decades-old murder of Lillie Belle Allen. Prosecutors alleged that Robertson, a police officer during the 1969 York Riots, yelled “White power!” and passed out ammunition to white gang members. One of those men, Rick Knouse, told a grand jury decades later that Robertson gave him rifle shells and told him to “kill as many niggers as you can.” Knouse told the grand jury he used the ammunition to fire on a car in which Allen was riding.

Robertson admitted to yelling “White power” but denied the rest. A jury acquitted him of murder charges, but Knouse was convicted of conspiracy in Allen’s homicide. The day after Robertson was arrested, Wolf publicly supported the mayor. “I was his campaign chairman during the primary,” he told the York Dispatch, “and if he wants me to do it in the general, I am willing to.”

Thirteen years later, Wolf primary opponent Rob McCord sharply questioned Wolf’s shielding of Robertson. But voters didn’t seem to care. And they were probably right not to. According to Eugene DePasquale, now auditor general, then York County Democratic Party chairman, while Wolf publicly backed Robertson, he privately worked to coax the 67-year-old out of the race. “Charlie was a particular personality,” DePasquale says. “Tom was concerned, we were all concerned, that if Charlie felt he was being forced out, he would stay in the race just to spite people.”

Prominent African-Americans in York have defended Wolf’s role in the Robertson matter so rigorously that he has gotten away with barely addressing the controversy. Wolf’s gambit worked, after all: Robertson did drop out. And political players in York think Wolf endured an uncomfortable public position to speed the exit of a divisive candidate.

TO THIS POINT, Wolf’s biography resembles that of many of his ancestors: an advantaged son who attended the best schools, took over the family business and served his community. But in more recent years, as Wolf attempted to transition from businessman to politician, his story grew more complicated.

By 2006, Wolf was ready to quit the family business. When I ask why, he lamely chalks it up to corporate succession planning. “I know I’m not going to live forever,” he tells me. His actions, however, suggest his true motivation was political ambition.

Wolf and his partners brought in Weston Presidio Fund V — an investment firm from Boston that conducts leveraged buyouts, deals that involve large loans. The transactions are legal and common, but they have a tendency to saddle the bought-out companies with big piles of new debt, often leading to cost-cutting and bankruptcies. Democrats successfully defined Mitt Romney as a self-dealing richie partly by pointing toward his involvement in just these sorts of transactions.

The investment firm put up $32 million, and a team of in-house managers, Wolf’s protégés, contributed another $5 million. But that wasn’t reward enough for Wolf and his two partners. So Weston and the new management team took out a $50 million loan from M&T Bank on behalf of the company. That freed up enough cash to pay Wolf and his partners about $20 million apiece. They also each got to hold onto an 11 percent share of the company.

Ron Anderson, a professor at Temple’s Fox School of Business, looked over the public information on these transactions. “It’s not common to see a family business sell to a leveraged buyout company,” he says, “precisely because LBOs leave the business at greater risk.”

He calls the deal “highly levered,” saying the transaction left Wolf’s old company with “a ton of new debt.” But he also sees how Wolf managed to sleep at night. “It doesn’t look to me like Wolf and his partners were out to screw anybody over,” he says. “He wasn’t reckless. You have to remember, in 2006 … everyone was cashing in home equity loans. This business surely looked healthy.”

AFTER THE DEAL, the pace of Wolf’s life seems to quicken, and holes start to emerge in his official narrative. Wolf likes to say that Governor Ed Rendell approached him about becoming revenue secretary. But when I asked Rendell about this, the former governor told me that Wolf came to him first. “He said he was thinking of running for governor in 2010,” Rendell said, “and he needed the experience.” Rendell also told me that Wolf had wanted the job of state treasurer, not revenue secretary.

Later, Rendell backtracked, writing in an email that Wolf “did not indicate he wanted to run for governor.” Rendell also changed his story on Wolf’s interest in the treasurer job, which is peculiar, since the Wolf campaign acknowledged that the candidate was first interested in the revenue position.

When I asked Wolf about the discrepancies between his campaign narrative and Rendell’s earlier recollection of events, he waved them away, saying, “Uhh, I don’t remember.”

The answer seems like a dodge, as if Wolf would prefer to pretend he was called to duty rather than acknowledge that he methodically built a CV for a future gubernatorial campaign. But there’s a trail suggesting Wolf is a lot more calculating than he lets on. He donated more than $250,000 to Rendell’s campaigns between 2002 and 2006. Rendell has acknowledged in the past that a big donation buys you a meeting (Wolf and his wife have donated more than $1.6 million to various state and county candidates since 1998), so it could be argued that Wolf didn’t just purchase this last primary election; he also sank some cash into his application for a position in Rendell’s cabinet.

One of Wolf’s closest friends debunks the notion that Wolf, all pluck and innocence, Forrest Gumped his way into politics. “I wasn’t shocked when Tom decided to run for office,” says Drew Altman, a health policy expert who served in the Carter administration, and a Wolf friend of 40 years. “We had spoken many times over the years about different offices he might run for. Should he run for Congress? That sort of thing … ”

Wolf served well, if briefly, as revenue secretary before resigning in 2008. He began appearing at statewide political events, like the annual Pennsylvania Society ball, in advance of an increasingly obvious 2010 gubernatorial run. He hired a pollster and finance people. Newspapers across the state covered his nascent campaign. Then, on January 20, 2009, as Wolf and his wife were in D.C. preparing to attend Barack Obama’s historic inauguration, the phone rang.

Members of his old management team, the group that had stayed behind to run the company, were calling to tell him the bank would probably foreclose. And soon.

The 2008 recession and the bursting of the housing bubble devastated the kitchen-cabinet business. The company’s new debt load made the crisis worse. Frances says she spent a couple of hours listening to one side of the conversation as her husband worked two phones, ringing up everyone involved.

They didn’t know, initially, if the business might already be beyond saving. Maybe Wolf would give up on his political run and the business both. “Then there was the possibility,” says Zimmerman, “that maybe Tom would return to the company, and who knows? Down the line he could look again at a run.”

Wolf returned, plowing $11 million of his own money into the operation and raising an additional $3 million-plus from each of his old partners. He used the cash to pay down and restructure the company’s debt and reinvented its mission, nudging his company from middleman toward sourcing and design. On his first day back, he told his employees: “We are now a 170-year-old start-up company.”

Wolf could hardly have mounted a credible run in 2010 against the backdrop of the smoking ruin of the Wolf Organization, a company bankrupted by a loan taken out largely to pay him. But Wolf and his wife point in a more personal direction: “I think he had to face the people who work there,” says Frances, “who … ”

“Who came to dinner,” says Wolf.

A few days after the call, after Wolf had decided he had to return, he sat down with Frances and his campaign managers in Philadelphia and made it official. His run was over before it started. When the words were out, Wolf cried.

“We really cried,” says Frances, “all together.”

“I figured the dream of running for governor,” he says, “was pretty much dead.”

AT ONE POINT during our interview, when Tom Wolf was discussing the details of his rebuilt business, he leaned forward, passionately, from his seat. “Yes,” he said, raising his voice. “I’m an amazing guy!”

Those in the room burst into laughter before catching themselves, like climbers sliding down a mountaintop. Wolf’s wife started making clucking noises, as if her husband shouldn’t have said that. One of the campaign guys shouted, “That’s off the record!” And Wolf himself made sure I knew: He had been joking.

We all soldiered on to another subject, but a certain awkwardness pervaded the exchange — a sense that a real meeting between candidate and voters is impossible. In the case of Tom Wolf, this seems like an opportunity lost. There is a politician in him, but his ad campaign’s conceit that he’s no ordinary politician seems true. There is little frame of reference for him in our politics: a self-funded candidate who came out of nowhere; a perfect stranger who appears to have shaped himself slowly, over decades, to the task.

Before I left, I asked Wolf about his parents’ Honest Tom stories. He acknowledged them almost sheepishly — “Yeah, they keep talking about that.” But as a credulous eight-year-old, Wolf says, he figured the great Stan Musial might actually have known he was crashing the clubhouse. Even in debunking this Honest Tom story, Wolf creates a new one.

Wolf and his wife offered me a brief tour of a few rooms on their first floor. The highlight was a look at some of the painted family portraits, which are a Wolf tradition. Wolf’s parents commissioned one of him at age 12, staring into a studious middle distance, an open book in his hand. In another portrait, painted by his wife, the adult Wolf appears worn, serious, with a melancholy expression in his eyes.

“He looks sad,” I observed.

I thought everyone might rush to disabuse me of this notion. The candidate can’t look sad. But the campaign people were in the other room. Frances merely said, “Yes,” and Wolf, a glint in his eye, played the moment beautifully, doddering his head a bit, as if tossed by the sadness he keeps inside. The instant conveyed a sense of play and seemed to acknowledge that behind the perfect campaign narrative, there is a real man.

After our interview, as he walked me toward my car under darkening skies, Wolf wished me luck at avoiding the rain.

“Good luck to you,” I replied.

He accepted my offer of a handshake but laughed in a way that struck me as odd at the time, as if he thought I’d said something silly. And then it occurred to me: The circumstances that created Tom Wolf and brought him to the threshold of the governorship are like the trees his grandfathers planted out back: deeply rooted, and not a product of chance.

Originally published as “Perfect Stranger” in the September 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.