Marijuana is Legal In Colorado. So When Will America’s Super-Racist Drug War End?

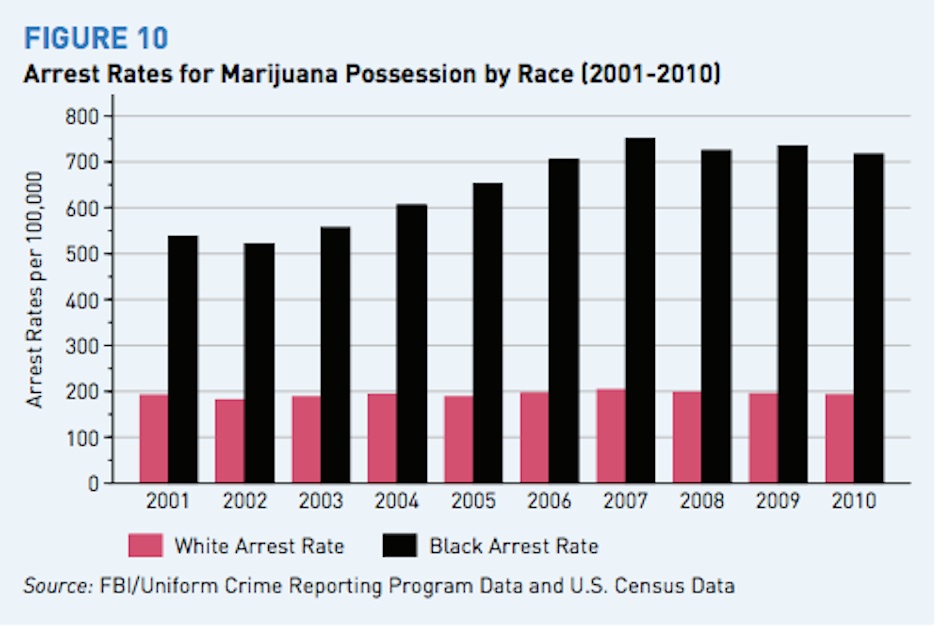

As consenting adults line up to purchase legal recreational weed in Denver, elsewhere blacks are four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana than whites.

According to a 2013 report by the ACLU, blacks are almost four times more likely than whites to be arrested for marijuana possession. It’s a sobering contrast to Colorado’s first week with legalized weed (it began on Jan. 1), following the passage of Colorado’s Amendment 64, passed with 55 percent of the vote in November 2012. The rollout has been largely successful (businesses banked about $1 million in sales that day) with long lines of consenting adults waiting to get their hands on the good stuff.

Chart from the ACLU’s “The War on Marijuana in Black and White”

In some areas, local governments are loosening their grip in response to the electorate, which may prove to be a good thing, though it remains to be seen if stakeholders in other parts of the country will be willing to concede. Profit will be the main incentive, as it has been.

Profit is the driving factor behind the war on drugs; the statistics only bolster the point that the public face of the menacing drug pusher and the violent drug abuser (irrespective of the drug itself) in America is a poor and/or brown one — this despite the fact that drugs push far beyond the concrete jungles of the inner cities, and dust the dwelling spaces of America’s elite and privileged. Still, the War On Drugs was not fought in the boardrooms of Wall Street, in the hushed bathrooms of Hollywood celebrity, nor on the pristine campuses of prep school academies and the lush greeneries of country clubs.

President Reagan’s war started in 1982 to reduce the trade of illicit drugs. Before him, President Nixon had already established two government agencies (The Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement and The Drug Enforcement Administration) to handle the drug trade at both the street and international levels. In August 1996, the San Jose Mercury News published the first in a three-part series called “Dark Alliance: The Story Behind the Crack Explosion” linking crack cocaine, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Nicaraguan Contra army.

The series, which has lead to intense speculation and conspiracy theorizing about the government’s role in the proliferation of drugs in urban city centers, read:

“For the better part of a decade, a San Francisco Bay Area drug ring sold tons of cocaine to the Crips and Bloods street gangs of Los Angeles and funneled millions in drug profits to a Latin American guerrilla army run by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency… This drug network opened the first pipeline between Colombia’s cocaine cartels and the black neighborhoods of Los Angeles, a city now known as the ‘crack’ capital of the world. The cocaine that flooded in helped spark a crack explosion in urban America… and provided the cash and connections needed for L.A.’s gangs to buy automatic weapons.”

As the Reagan Administration focused on its war, drug abuse was criminalized and the police state grew within urban communities while Nancy Reagan offered pithy advice to kids to “Just Say No.” Following the overdose death of Len Bias, a promising young basketball star, in 1986, both drug sales and drug abuse became criminal and political thanks to (not-so-subtle) fear baiting that correlated drugs with race, poverty and violent crime.

Since Reagan’s ’80s, there’s been a drastic expansion of the prison population and number of prisons built in the United States, thanks, in part, to the sentencing disparities for crack and cocaine that disproportionately jailed people of color with tougher sentencing requirements. (In 2011, President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act into law, reducing the disparity.) Still, America has the highest incarceration rate in the world.

Prisons are profitable business for private companies as well as the state, particularly in areas in need of economic revitalization. Criminalizing drug use and broken drug policies have kept business booming with prisoners as a new labor force for private contractors. Here in Philadelphia, a shiny new $400 million dollar jail was built, even as many of the city’s public schools closed their doors.

Both misdemeanor and felony marijuana possession convictions have devastating effects for both the individual and his or her community through disenfranchisement, including drivers license suspension, loss of voting rights, revocation of professional licenses, denial of educational financial aid, and restricted access to food stamps. One out of 100 American adults is behind bars, according to a CNBC.com report; one out of 32 maintains a relationship with the Prison Industrial Complex through probation, parole or prison. Punishments continue well after criminal sentencing and time served, crippling members of the re-entry population, and gravely impacting their abilities to contribute their local community or society at large. With few options to move forward, it practically invites recidivism, which is as mindless as any drug could be.

Follow @MF_Greatest on Twitter.