No, the Cops Aren’t Banning Protesters From Facebook

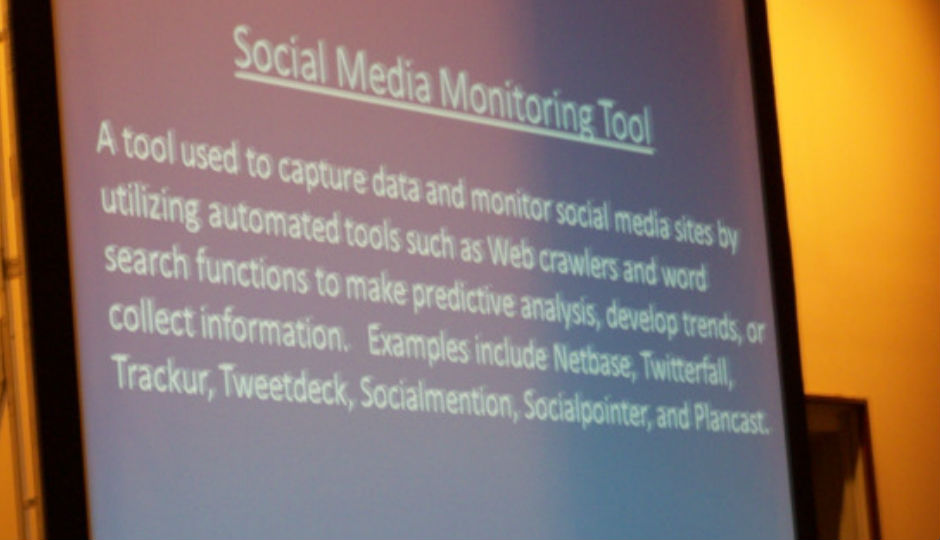

It should come as no surprise that police departments monitor social media. After all, as a speaker revealed during a panel at last week’s International Association of Chiefs of Police conference, roughly 96 percent of law enforcement agencies utilize social media, and more than 86 percent for “investigative purposes.”

At least, that’s according to Kenneth Lipp, the Philadelphia-based investigative journalist at the center of what Chicago Police Department Lt. Steven Sesso calls a “headache.”

Since the IACP conference’s closing, Lipp has been posting photos and videos from the event’s panels and showroom floor, along with blog posts highlighting the available police swag and attending heavy-hitters. It was essentially a who’s who of modern law enforcement, the massive conference having filled every bit of the PA Convention Center’s 679,000 square feet for a solid five days.

The headache to which Lt. Sesso refers, though, comes not from any helicopters or armored personnel carriers that were for sale, but a statement from an unnamed, unscheduled speaker from the Chicago Police Department indicating an apparent relationship between the agency and social media giant Facebook. According to Lipp’s original blog post, the nature of that relationship—allegedly built through Facebook’s chief security officer, Joe Sullivan—was to “block users’ from the site by account [person], IP, and device … if it is determined they have posted what is deemed criminal content.” Additionally, Sullivan was listed as a speaker for that same panel.

In the right light, that’s pretty spooky, but how that statement turned into “Chicago PD wants to block protesters from organizing over social media” is a little more convoluted. Lipp never actually associates Chicago PD’s statement with direct targeting of protesters, that link came pretty much directly from surveillance blog Privacy SOS. An article posted by “sosadmin” reads:

“Is Facebook really working with the police to create a kill switch to stop activists from using the website to mobilize support for political demonstrations? How would such a switch function? Would Facebook, which reportedly hands over our data to government agencies at no cost, block users from posting on its website simply because the police ask them to? The company has been criticized before for blocking environmentalist and anti-GMO activists from posting, but Facebook said those were mistakes. Let’s hope this is a misunderstanding, too.”

So, essentially, wild speculation on their part. Unfortunately, that got picked up by noted propaganda outlet Russia Today, which posted an article last week stating that that apparent agreement could “allow law enforcement to keep anything deemed criminal off the Internet—and even stop people from organizing protests.” And, at that point, it became an international game of whisper down the lane.

That game, as we know by now, results in pretty much nothing but bunk, a fact to which Lt. Sesso can attest. “As far as we know, the panel conversation concerned gangs and gang crimes,” he says. “It had nothing to do with infringing on First Amendment rights or protest.” Additionally, Sess0 insists that there is no “special relationship” between his department and the world’s largest social media network, and that the speaker at the IACP conference expressed an interest in using “social media outlets like Facebook” to enhance their policing.

Zuckerberg and Co., for their part, note in a brief press release following the conference that “content reported by law enforcement is subject to the same review applied to reports from anyone using Facebook” and also denies any “special relationship” between Facebook and the police. There is, however, a “huge social media component” to Chicago PD’s policing, says Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy in a recent DNAInfo article. What that component is exactly, though, he wouldn’t discuss. Again, though, that that component exists shouldn’t be surprising.

The removal of a user, Sesso says, would only be in connection with an actual criminal act, like offering drugs for sale or promoting evidence of crimes committed in relation to the gang element he had discussed. In that sense, Chicago PD’s policing—and therefore the policing of other departments utilizing social media similarly—would only interact with Facebook where Facebook’s terms of use are concerned. However, that particular area of policing remains largely unregulated, which explains why a vast majority of police departments are seeing an investigative use for social media. A gray area, sure, but certainly not the First Amendment issue Lipp’s initial reporting has spun into.

All that, though, doesn’t explain how Facebook’s CSO ended up on the IACP’s program as a speaker. Facebook also denies that their Joe Sullivan was scheduled to speak, claiming they they’re unsure of how his name appeared on the program. A CSO of Sullivan’s status partnering with a police department for this type of activity is unlikely, but he probably has at least had contact with some of the IACP’s attendees given the uptick in social media-based policing. However, because the Philly PD happens to count a Joe Sullivan among its own ranks, this may just be a simple case of mistaken identity.

The Philadelphia Police Department’s chief inspector Joe Sullivan, notably, is extremely active on Twitter, maintaining a constant social media presence that reveals that he attended this year’s IACP. In fact, Sullivan says he was the detail commander for Philly PD’s part of this year’s conference, meaning that he essentially organized the logistics for many of the week’s events, along with their setup and teardown.

“Someone either has the same name,” he says, “or they transposed mine on there.” That, or there was a massive miscommunication between Chicago PD’s representative—who Lipp says was not a “hacker cop”—and Facebook. Another game of whisper down the lane.

But while it doesn’t seem likely that police departments are developing ways to remove swaths of civil liberties activists from social media to crush their organizing ability, there still is cause for concern—that concern, of course, being that many of us were surprised enough by the IACP announcement to allow it to spiral out of control.

“We’re not talking about a widespread shutout of protesters on social media,” Lipp says. “In fact, there’s more of a benefit not to ban people from participating in social movements online because they’re hashtagging their political preferences.”

In that sense, utilizing social media while participating in something like a protest is most closely akin to strapping on a digital dog collar that informs your master of not only your location, but where you’re planning on going next and how. With a few scripts and some computing power, aggregating all that data can produce a pretty accurate picture of the situation at hand.

Based on a follow-up from Lipp, it’s pretty clear that mostly anyone participating in a large gathering of people—especially in large groups like protests—on any serious level is probably being surveilled. In a year where government organizations have been caught redhanded operating a full-blown surveillance state, that bit of information is hardly news. But with that in mind, police departments doing essentially the same in the largely open-source information bazaar that is social media simply makes sense. Cutting off the population providing that information does not.

As a result, those of us attempting to organize a message en masse via social media don’t seem to be facing any dangers to our First Amendment rights. However, with both City Paper censored from Twitter and Victor Fiorillo temporarily removed from Facebook over a tiff with a publicist, those of us attempting to communicate messages on a large scale seem to be in a little bit of trouble. Only this time, it’s not coming from the police.