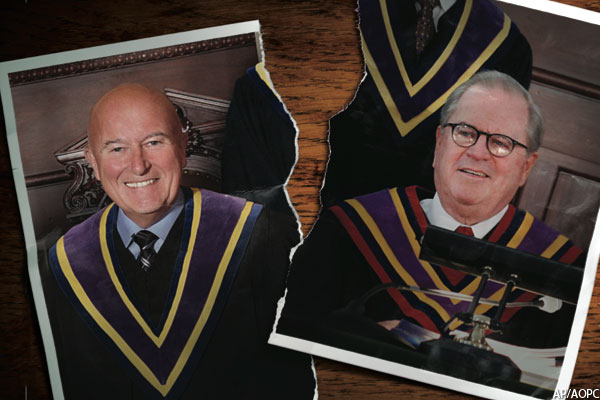

War in the Supreme Court: Ron Castille and Seamus McCaffery Just Can’t Get Along

Late last year, Ron Castille, chief justice of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court, decided he couldn’t take it any longer. Seamus McCaffery—one of seven justices on the court, and the only other one from Philadelphia—had been including a certain tag line on emails he sent from his court account. Courtesy of Ernest Hemingway, the tag line read: “Certainly there is no hunting like the hunting of a man and those who have hunted armed men long enough and liked it, never generally care for anything else thereafter.”

McCaffery, a former Marine, a former Philly cop, a guy who carries a gun and rides a Harley, takes great pride in his toughness. But Castille could no longer abide the bluster, the preening. He himself lost his right leg while serving in Vietnam—on his 23rd birthday, no less—and he was once a hard-ass prosecutor in Philadelphia’s D.A.’s office before becoming D.A. himself. He knew all about toughness.

So last fall, Castille sent McCaffery an email, one on which he cc’d their fellow justices. It read, in part:

Your military service while honorable, did not involve combat action against armed enemy forces as did my service as a Rifle Platoon Commander in the Marines in Vietnam. In fact, I did “hunt” armed men and I can tell you and your email recipients that it is a nasty, dirty business and, while sometimes required by national policy, it is not an activity to be extolled, especially by anyone who does not have the personal experience in the activity.

Castille knew, of course, that sharing his email with the other justices would be highly embarrassing to McCaffery. He didn’t care. His feelings about the man had been building for some time, and their relationship had been deteriorating.

It would soon get worse.

At the end of last year, in a report Castille commissioned about Philadelphia’s corrupt Traffic Court, McCaffery was accused of using his power in an unseemly and perhaps illegal way: He had driven his wife, Lise Rapaport, to Traffic Court on Spring Garden Street for a hearing on a ticket and, while the hearing took place, summoned a top court administrator out to his car for a conversation. Rapaport was found not guilty.

With Ron Castille’s blessing, the Traffic Court report was given to the Inquirer, which did a series of front-page stories on it. Naturally, that didn’t sit well with Seamus McCaffery, who has denied any wrongdoing.

Then a second matter came up. The Inquirer wrote about fees that Rapaport, a Harvard-trained lawyer, received for referring cases to law firms while she was employed by McCaffery as his chief Supreme Court aide. Eleven of the law firms that paid Rapaport—one referral fee was $821,000—have argued cases before the Supreme Court while McCaffery has been on the bench.

When that story broke, Castille—who was first elected to the court in 1993 and has been chief justice since 2008—told reporters he was worried about “conflicts of interest and the appearance of impropriety.” His opinion wasn’t shocking, but it was an unusual slapdown; chief justices of a Supreme Court almost never publicly rebuke a fellow robesman. What’s more, there was the question of how the Inquirer suddenly landed on the Rapaport referral-fee story when those payments, which McCaffery’s lawyer said were routine and proper, had long been a matter of public record. While Castille denies alerting the paper to the story, he probably was not unhappy that McCaffery was being embarrassed.

In mid-June, McCaffery’s trouble seemed to grow worse. The Inquirer reported that the FBI had opened an investigation into those referral fees his wife received. Meanwhile, the Legal Intelligencer wrote that McCaffery had contacted a high-level Philadelphia Common Pleas administrator last year about civil cases—and that in two of the cases, a law firm that had paid a referral fee to Lise Rapaport was involved. McCaffery’s lawyer says there is no FBI investigation, but Ron Castille told WHYY that he has “no reason to believe the allegations of an FBI investigation against Justice McCaffery are not true.” He added, “So I think if I was Justice McCaffery, I’d start rethinking my position on the Supreme Court.”

We still don’t know how Seamus McCaffery’s problems will play out. But one thing is patently clear: This is war, between Ron and Seamus. It is ugly. McCaffery now actively avoids his chief justice, having as little to do with him as possible. Which is fine by Ron Castille, who seems determined to help get “Famous Seamus,” his nickname for McCaffery, into as much trouble as he can.

According to sources close to the court (more than 50 people were interviewed for this story), the feud is, in part, about power. One of the roles the state Supreme Court plays is to oversee Philadelphia’s judiciary—a job handled by a justice who’s appointed by colleagues as liaison to the First Judicial District. Given his two decades as a Philly cop and his decade on the city’s Municipal Court bench, not to mention his natural bent for schmoozing union guys and City Councilmen with equal aplomb, McCaffery has long seen himself as the perfect guy for that job. Indeed, he’s craved it ever since he was elected to the court in 2007, once telling a court insider that he didn’t run for the Supreme Court to sit in an office and write legal opinions; no, he wanted to oversee Philadelphia’s courts.

But Ron Castille kept the role of liaison for himself even when he became chief justice, though the chief was far too busy for the position. The reason he kept it, McCaffery believes, was to block him from getting it. He’s sure it’s personal.

And he may be right about that, because Ron Castille thinks that “Famous Seamus” is a poseur, a phony, a made-up person. What’s more, Castille believes that McCaffery wants to rule a political fiefdom in Philadelphia. A judge, however—by decree of the state’s ethics code—can’t be involved in politics. He must stay above the fray of raising money for elections, and ward meetings and the like. Especially a justice of the Supreme Court, which oversees all the other courts in Pennsylvania. In a way, that issue, too, is personal between the two men, because Castille the war hero believes fervently in a certain bottom line, in playing by the rules.

And then there is the reputation of the court itself. For decades the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has been something of a joke—a place known for petty squabbles and occasional outright corruption. Earlier this year, justice Joan Orie Melvin resigned after being convicted of using taxpayer resources for campaign purposes. Even Castille himself tarnished the court’s reputation with his bungled handling of the construction of a new Family Court building in Philadelphia.

In Castille’s remaining time as chief justice—he’s required by law to retire next year, when he turns 70, though a federal lawsuit has been filed that would allow him to stay on longer—he seems determined to do everything he can to protect the court’s reputation and, by extension, his own legacy. If that means going to war with Seamus McCaffery, then that’s what Ron Castille is quite willing to do.