The Founding Fathers Would Have Been Protesters at Occupy Wall Street

Last week I drew criticism from some in the state’s business community for daring to suggest that the decision to potentially turn essential public services over to the corporate sector might require a bit more scrutiny than I felt the Governor’s new panel on privatization was apt to provide.

In the wake of the sometimes heated, but more often courteous exchange of written dialogue with members of the panel and others who represent the interests of the private sector, I decided to give my typing fingers (all four of them) a chance to regain some of their strength and focus on a less controversial topic this week.

Then I saw General Electric chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt on CBS’s 60 Minutes on Sunday, and I decided that discretion would have to wait a week.

From the relative safety of my kitchen table I joined Immelt (who in January was named by Barack Obama to chair the President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness) on a 20-minute whirlwind tour of his company’s facilities in the U.S. and Brazil as he expounded on the globalization of capital, the inequity of corporate tax policy and how GE is helping America by giving cutting-edge avionics technology to China so it can better compete with Boeing, another U.S. company.

Then came the coup de maitre; at the end of the segment Immelt was asked point-blank by correspondent Leslie Stahl if corporations have a civic duty to boost American jobs, to which the executive, trying his best to appear contemplative, responded with a shake of his head:

“I work for investors,” he said. “Investors want to see us grow earnings and cash flow, they want to see us be competitive, they want to see us prosper.”

And there it was, plainly spoken from the mouth of one of the most powerful business executives in the world: We are here to make money. Period.

I commend Immelt for his candor. He was asked a difficult question and without a hint of reticence he gave Stahl the straight dope, no punches pulled. In so many words, he said what critics of unrestrained capitalism have been saying for decades: A corporation has no duty except to its shareholders, which is why they can’t be trusted to do right by the rest of us.

But here’s the thing: As President Obama’s “jobs czar,” Immelt the man has the ultimate civic duty to increase American employment, even (it must be said) if the solutions are not always in GE’s best interest. His job (the one the president tasked him with, at least) is to do right by America’s unemployed workers.

Does anyone but me see a problem here?

Immelt doesn’t; nor apparently does Stahl, who didn’t raise the question of a possible conflict of interest. As for me? Well, I just couldn’t help myself. I decided to dig a little further to find out how corporations got so powerful and why they make so many people (myself included) so uncomfortable.

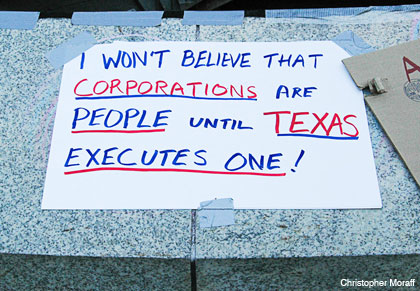

Since the first group of protesters sat down in Zuccotti Park on September 17th (to be joined within weeks by Occupy groups in cities across the nation, including Philadelphia) corporations and their enablers on Wall Street have been singled out for collective rebuke in chants, signs and slogans. But the rhetoric that paints a picture of the corporation as an omnipresent force belies its humble beginnings and the concerted efforts of businessmen, attorneys, lobbyists, judges and lawmakers to elevate it to its current status.

The founders’ lamentations against “monied corporations” established a vehement distrust of such organizations until well into the Civil War, when the rise of the industrial revolution saw the first major expansion of corporate rights. Early corporations were extremely limited in scope and lifespan, prohibited from owning stock in another corporation, and in their earliest iterations, their charters forced shareholders to remain personally liable for a company’s misdeeds. It wasn’t until 1886, after years of effort, that Supreme Court Justice Stephen Field—a shill for the railroad industry—used his power on the bench to hijack the 14th Amendment, which offered former slaves equal protection under the law, to extend human rights to corporations. Two years later Field enshrined the decision in the annals of law, and the rest, as they say, is history. Over the course of the next hundred years, the intertwined interests of commerce and government ensured that the rights of corporations would continue to grow, and today organizations that were once prohibited from owning property can sue and be sued, borrow money, buy stock, influence ballot questions, and contribute unlimited monies to political campaigns.

All this might not be a problem if it weren’t for a variable unique to corporations: the fiduciary duty to create profits for shareholders. This guarantees that nothing, not the environment, American jobs or worker safety, is more important than making money. It is a corporate executive’s duty to do everything legally possible to raise profits. This is why regulations are so important; they offer a legal counterbalance to fiduciary duty. It’s also why so many U.S. jobs wind up in foreign countries where labor and production costs are cheaper.

Corporations currently employ a fifth of all American workers, which means more than 20 million of us owe our livelihoods to the largest business conglomerates the world has ever seen. They also are unthinking, unfeeling and bereft of values, morals and responsibility. These are not the American-as-apple-pie companies of post-war America. This here is a different breed altogether.

Back in 1953, when “Engine” Charlie Wilson found himself in a similar position to Immelt, tapped for government service and facing a round of confirmation hearings for Secretary of Defense, the chief executive of General Motors was asked if, in the course of his government duties, he could make a decision that was adverse to the interests of GM. Wilson responded with the famous and oft-misquoted retort that he could not conceive of such a situation, “because for years I thought what was good for the country was good for General Motors and vice versa.”

As arrogant as it might sound on reflection, the statement had some truth to it. In the 1950s more than half the vehicles on America’s roads were GM-made, and most, if not all, were built in the U.S. In 1955 the company employed 624,000 Americans (today that number is just over 68,000, or roughly 30 percent of its workforce).

Today the largest U.S.-based enterprises are globalized institutions whose customers, employees and profits (thanks to tax loopholes) are concentrated overseas. According to a survey of the leading corporations conducted in April by the Wall Street Journal, U.S.-based multinationals cut domestic employment by nearly three million workers over the last decade, cuts that in almost every case were mirrored by hiring efforts overseas. In 2010 fewer than 13 percent of Coca Cola’s 93,000 employees were America-based.

Where jobs have been cut across the board, in almost every case U.S. workers took the brunt. Take Immelt’s GE as an example. The Journal reports that between 2005 and 2010, the company eliminated 28,000 American jobs compared to just 1,000 cuts made overseas. More than half of GE’s employees are located in foreign countries. (Immelt says the shift has been driven by customer trends, not labor costs, but that argument loses air when you consider how many U.S. products are manufactured in places like India, China and Pakistan.) Similarly, Oracle and Cisco both have more employees overseas than in the U.S. Meanwhile, all three companies use complex tax instruments, such as transfer pricing, to avoid paying much, if anything, in the way of U.S. federal taxes. It begs the question: Do they even qualify as American companies anymore?

In a speech in Philadelphia in 1936, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt warned about the “economic royalists” that were carving out “new dynasties” of power across the country.

These “new kingdoms were built upon concentration of control over material things. Through new uses of corporations, banks and securities, new machinery of industry and agriculture, of labor and capital—all undreamed of by the Fathers—the whole structure of modern life was impressed into this royal service … It was natural and perhaps human that the privileged princes of these new economic dynasties, thirsting for power, reached out for control over government itself. They created a new despotism and wrapped it in the robes of legal sanction. Private enterprise, indeed, became too private. It became privileged enterprise, not free enterprise.”

He could be making that speech today. Make no mistake, the corporation is still the dominant institution in in the world. Like the church and the aristocracy of old, business conglomerates like GE, Chevron, Cisco and Merck have broken the bonds of nationality and embarked on a global agenda—in their case, to create an atmosphere for maximizing profits and then following through on that mission.

Now please excuse me while I do some finger exercises. I have a feeling it’s gonna be a busy weekend.

Writer and photographer Christopher Moraff is a news features correspondent for the Philadelphia Tribune and a contributing writer for the Chicago-based magazines Design Bureau and In These Times, where he serves on the board of editors.