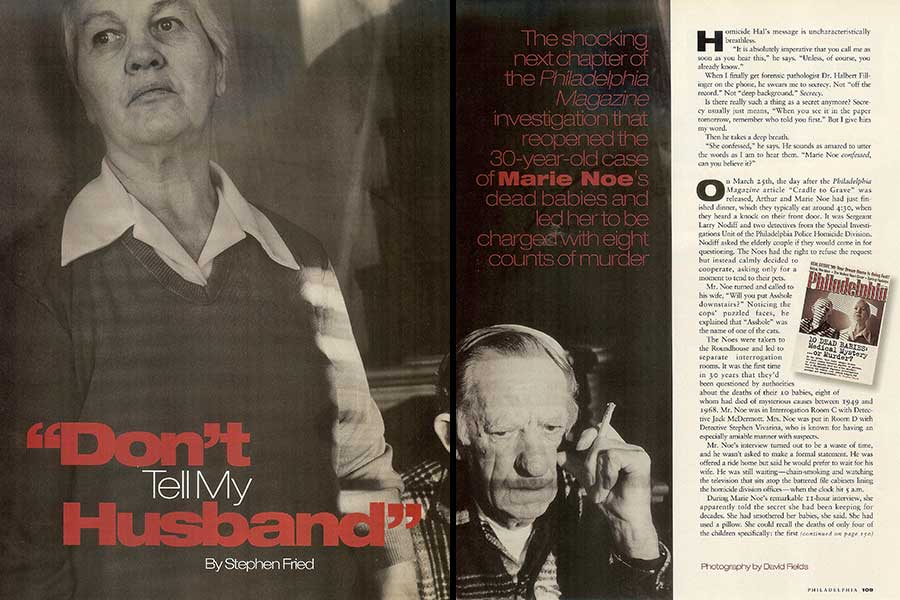

“Don’t Tell My Husband”

The shocking next chapter of the Philadelphia magazine investigation that reopened the 30-year-old case of Marie Noe’s dead babies and led her to be charged with eight counts of murder.

From the September 1998 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

HOMICIDE HAL’S MESSAGE is uncharacteristically breathless.

“It is absolutely imperative that you call me as soon as you hear this,” he says. “Unless, of course, you already know.”

When I finally get forensic pathologist Dr. Halbert Fillinger on the phone, he swears me to secrecy. Not “off the record.” Not “deep background.” Secrecy.

Is there really such a thing as a secret anymore? Secrecy usually just means, “When you see it in the paper tomorrow, remember who told you first.” But I give him my word.

Then he takes a deep breath.

“She confessed,” he says. He sounds as amazed to utter the words as I am to hear them. “Marie Noe confessed, can you believe it?”

ON MARCH 25TH, the day after the Philadelphia Magazine article “Cradle to Grave” was released, Arthur and Marie Noe had just finished dinner, which they typically eat around 4:30, when they heard a knock on their front door. It was Sergeant Larry Nodiff and two detectives from the Special Investigations Unit of the Philadelphia Police Homicide Division. Nodiff asked the elderly couple if they would come in for questioning. The Noes had the right to refuse the request but instead calmly decided to cooperate, asking only for a moment to tend to their pets.

Mr. Noe turned and called to his wife, “Will you put Asshole downstairs?” Noticing the cops’ puzzled faces, he explained that “Asshole” was the name of one of the cats.

The Noes were taken to the Roundhouse and led to separate interrogation rooms. It was the first time in 30 years that they’d been questioned by authorities about the deaths of their 10 babies, eight of whom had died of mysterious causes between 1949 and 1968. Mr. Noe was in Interrogation Room C with Detective Jack McDermott. Mrs. Noe was put in Room D with Detective Stephen Vivarina, who is known for having an especially amiable manner with suspects.

Mr. Noe’s interview turned out to be a waste of time, and he wasn’t asked to make a formal statement. He was offered a ride home but said he would prefer to wait for his wife. He was still waiting — chain-smoking and watching the television that sits atop the battered file cabinets lining the homicide division offices — when the clock hits 5 a.m.

During Marie Noe’s remarkable 11-hour interview, she apparently told the secret she had been keeping for decades. She had smothered her babies, she said. She had used a pillow. She could recall the deaths of only four of the children specifically: the first three, Richard in 1949, Elizabeth in 1951 and Jacqueline in 1952, and the fifth, Constance, in 1958. She said she did not remember what she had done in 1955 to Arthur Jr., the baby born exactly nine months to the day after she claimed to have been raped by a stranger and left bound with her husband’s ties in the bedroom closet. Nor did she remember what she had done to the babies whose deaths received so much national media attention in the 1960s: Mary Lee in 1962, Cathy in 1966 and Little Artie in 1968. But she did not deny causing those later deaths.

After her confession was typed up, Marie read it over and signed it. She seemed relieved. But as she left the interrogation room with the three officers, she became skittish.

“Don’t tell my husband what I told youse,” she whispered.

THE MARIE NOE CONFESSION remained secret for almost a week, which seemed an eternity for those in the know but wasn’t nearly as long as the D.A.’s office had hoped to keep the case to itself. A few shards of information leaked out to the Inquirer late Tuesday night, March 31st, and an unconfirmed report of the confession ran the next morning.

A media feeding frenzy ensued, with camera crews camped out on the Noes’ block in West Kensington, waiting for a glimpse of the spent, slow-moving couple: a tiny red-faced man with a habitual cigarette and his broad-shouldered wife, who appeared blank until provoked. Their story made national nightly news, the New York Times, the Washington Post and all the morning shows. Several days later, it led the TV magazine show Dateline NBC. At the height of the coverage, a local defense attorney named David Rudenstein announced that he had been retained by the couple and that Marie Noe’s so-called confession was inadmissible because she had been interrogated for 11 hours without a lawyer present. He contended that her mental condition that evening did not allow her to make an admissible confession.

Seeing Rudenstein on TV in his cream-colored three-piece suit did not thrill some involved with the case. Rudenstein is considered smart, but he’s known for over-the-top courtroom antics, often involving props. He once produced a Pinocchio doll to drive home his point about a witness’s alleged lies, and he has also done bits with a plastic shovel, a toy Liberty Bell and a scarf. Rudenstein did make one other provocative point about Marie Noe. “I’ve never seen anyone confess to five murders and be released from police custody,” he told reporters. And as weeks, then months passed without word from authorities, observers began to wonder what had happened to the case.

THE POLICE and the D.A.’s office were lying low because they knew it would take a great deal of investigation to make a case against Marie Noe, even with her signed confession. Except for what she had told them, much of what they knew about the case came from the magazine article, which included current interviews with experts and an analysis of the ancient investigative files, some going back to 1949. But investigators understood that many of the accusatory statements in those old files might not be available to prosecutors if the case went to trial. Unless those who had been interviewed back then were still alive and could come into court to corroborate what they had said, some powerful past statements might not be admissible as evidence. Many of the statements had been taken by the medical examiner’s lead investigator, Joe McGillen, who was still very much alive. But McGillen’s testimony about what he’d been told could be considered hearsay.

This was ironic because the cause might never have been reopened, and the confession never obtained, if not for McGillen. It was because of the retired investigator’s memory and files that the magazine and later the police could re-examine the case. The investigative file itself was extraordinarily detailed: McGillen and his partner had gone so far as to create a wall-size chart of three generations of the Noes’ families, showing what happened to every kid born to any of them. But as impressive as McGillen’s enterprise had been in the 1960s, what mattered most in the 1990s was that he knew where to find his files.

When McGillen left the M.E.’s office in 1984 to live quietly with his wife in the Northeast, distracted only by his grandchildren and his job scouting high school and college prospects for Major League Baseball, he elected to retain his personal copies of the case files. He kept them in a box in his garage until his youngest daughter moved away and her room was turned into a den. The box sat on the den floor for years.

That’s where it was when I first contacted McGillen in November 1997, at the suggestion of a former member of the M.E.’s staff. By that point, I was frustrated with the Noe case, which I had been investigating for several months. My interest began when my editor at Bantam gave me a new book on sudden infant death syndrome that the house had published, The Death of Innocents. It explained the new science of SIDS and called for the reinvestigation of past multiple child deaths, focusing on the landmark case of Waneta Hoyt, a Syracuse woman who killed her five babies between 1964 and 1971. (Hoyt died in prison four days after Marie Noe’s arrest.) The Noe babies are mentioned several times in the book, but the family is referred to by a pseudonym.

I first asked the husband-and-wife authors, Richard Firstman and Jamie Talan, to cover the Noe case for Philadelphia Magazine. They declined but encouraged me to pursue it, sharing some materials and recounting their attempts to get Philadelphia authorities interested in the case back when they were researching the book. Talan remembered calling D.A. Lynne Abraham several times about the Noes in 1995 but never getting a call back. She did get through to the D.A.’s homicide chief at the time; she recalls him dismissing her plea that he look into the deaths. (This is not current chief Charles Gallagher, who has aggressively pursued the case since March.) Talan, who had nightmares about Marie Noe’s babies, wished me better luck.

After I contacted Dr. Molly Dapena, the SIDS expert who had worked on several of the Noe baby autopsies, and she expressed her suspicions about the deaths, I enlisted the help of two members of the Vidocq Society, the Philadelphia-based sleuthing club that delves into old, unsolved crimes. Dr. James Lewis brought me to a pathologists’ meeting where I was able to buttonhole Dr. Fillinger and secure his crucial support. Private investigator William Fleisher introduced me to Sergeant Larry Nodiff, who supervises the Philadelphia Homicide detectives who look into the “cold” cases. I later learned that Nodiff had quietly reactivated the long-dormant Noe case, after I asked him about the babies.

But it was still difficult to get even basic information about the case. I was unable to make a complete list of all the children’s names and dates of birth and death until after my first meeting with the Noes, in the late fall. They told me that most of the papers pertaining to their children were destroyed when their basement flooded. A friend had made them a new set of birth and death certificates, which they let me borrow, along with their photo album.

My goal was to gather everything that had ever been known about the deaths and let the experts come to their own conclusions, based on current advances in pediatric pathology. The Noes themselves told me they had always wanted to know more about what had happened, and they also understood that some old SIDS cases were being reopened as murders. Both repeatedly denied having anything to do with their children’s deaths. However, Mrs. Noe did give an interesting answer to a query about the sodium amytral or “truth serum” interview she underwent in 1949 to treat her hysterical blindness after the death of her first child. I asked if she recalled being afraid of saying something under the “truth serum” that she didn’t even know herself relating to her son’s death. She said, “I think that … whatever came out of that session, no matter what was said, I think I would have been relieved … When I asked the young doctor [who conducted the interview], he said, ‘Don’t you worry about it; you said nothing wrong.’“

I asked again, “You were willing to accept anything you would have said?”

“I’da been glad to get it over with,” she replied. “I would have been glad to know, because when you lose something as precious as a child, you lose half your life.”

Even with the information from the birth and death certificates, attempts by police to locate copies of their Noe files so they could respond to my questions proved fruitless. The medical examiner’s office was unable to produce its files or the autopsy reports on most of the children until the original case file numbers were provided to me by McGillen.

It turned out that McGillen was the only one who could locate a full copy of the police and M.E. reports, which also included crucial medical information. As Marie Noe’s obstetric surgeon, Dr. Salvatore Cucinotta, found when he tried to request his own records from St. Joseph’s Hospital, healthcare facilities now are only required to keep records going back seven years. The M.E. had subpoenaed all the hospital records back in the ’60s, and McGillen’s files contained abstracts of many medical records important to the case.

Marie Noe’s confession in late March was the news McGillen and his family had been waiting for since 1968. It almost came too late. When McGillen and I began talking, his wife, Elaine, had just found out that the cancer she had been fighting since 1993 was spreading. The quiet reopening of the Noe case was one of the couple’s only distractions from the pain and the cycles of radiation treatments. In March, when the news of the confession broke, Elaine was still well enough to enjoy the fact that her husband finally felt he had been vindicated. In May, she died at the age of 69.

ON WEDNESDAY, August 5th, a black, unmarked Ford Explorer pulls up in front of Arthur and Marie Noe’s West Kensington home at 6:05 a.m. Sergeant Larry Nodiff hops out, along with the two detectives who have been working the case with him.

Steve Vivarina, who led the interrogation with Marie Noe, chews nervously on his plastic coffee stirrer as he knocks on the door. There’s no answer. He rings the bell. Still no answer. He looks up: An air-conditioner is running loudly in the second-floor bedroom window.

An older Hispanic man sitting on a nearby stoop says something in Spanish, poking the air repeatedly with his finger. They realize he is trying to tell them to ring the bell repeatedly, so Vivarina does.

After nearly 10 minutes of ringing and knocking, Arthur Noe peers through.

“We have an arrest warrant for Marie,” Nodiff replies. She is being charged with eight counts of murder.

The couple gets dressed and puts the dogs and cats in the basement. Marie’s face is blank. Art is cooperative but crabby, especially after he tries to call his lawyer on a phone with oversize buttons and gets a wrong number.

The couple sits together in the backseat of the Ford Explorer as they are driven to the Roundhouse. Marie is not handcuffed, but the doors are safety-locked. Everyone is quiet. The only sound is Detective Vivarina chomping on that coffee stirrer.

“Will you please stop that?” Art snaps. Then he criticizes the other detective’s driving: “Keep your eyes on the road, Jack.”

Marie has been characteristically quiet. Art turns to her. “I guess you won’t be home for your birthday,” he says.

In three weeks, she’ll be 70. If her children had lived, the oldest, Richard, would be 49 and the youngest, Little Artie, would be 31.

The Explorer pulls into a parking bay below the Roundhouse, and Marie is taken away to be processed. Her husband is escorted up to Homicide to use the phone and wait for the lawyer. After calling, he lowers himself into a chair just outside Interrogation Room D, where Marie gave the statement she didn’t want him to hear.

Mr. Noe lights another cigarette and looks up at a detective leaning against a desk. “Do you think she did it?” he croaks.

But he already knows the answer.

© 1998 Stephen Fried