NextUp: The Navy Yard-Based Biopharma Company Engineering T-Cell Receptors to Destroy Cancerous Solid Tumors

After promising Phase II data, Adaptimmune is on track to file their drug candidate, afami-cel, for FDA approval next year.

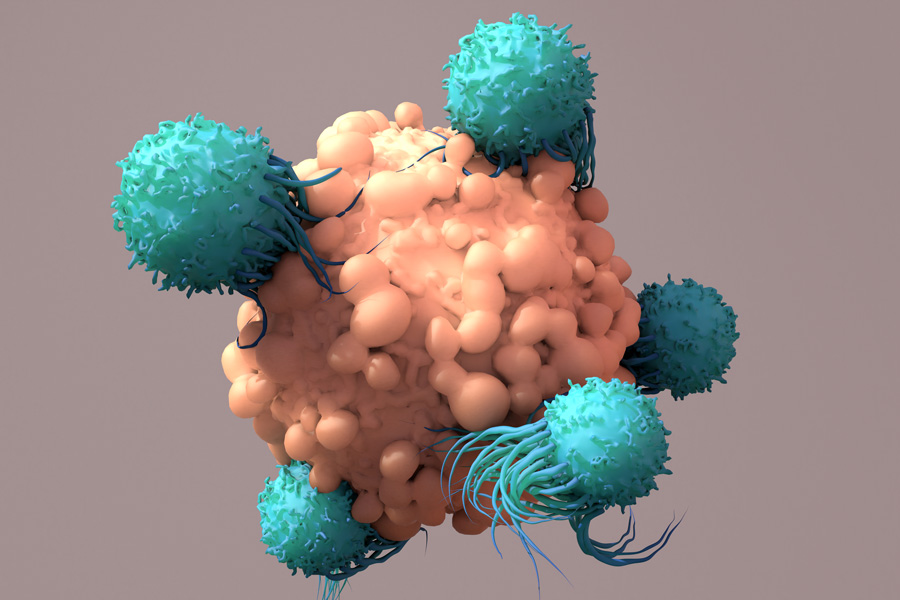

An illustration of T cells attacking a cancer cell. Image by Design Cells/Getty Images

“NextUp” is a weekly NextHealth PHL feature that highlights the local leaders, organizations and research shaping the Greater Philadelphia region’s life sciences ecosystem. Email ccunningham@phillymag.com with pitches for NextUp.

Who: Around the turn of the millennium, Bent Jakobsen, a scientist at the University of Oxford, successfully stabilized T-cell receptors (TCRs) — molecules responsible for finding diseased cells in the immune system — in liquid media. This breakthrough was monumental because TCRs are membrane-bound, held together only by the T-cell itself, meaning they typically fall apart when in liquid media without the T-cell. Their instability made it extremely difficult and nearly impossible to engineer them, but Jakobsen’s discovery opened up new doors in the field of targeting tumors. Rather than engineering antibodies — which are naturally stable in liquid — scientists could now use TCRs to go after proteins expressed inside tumor cells, not just surface proteins.

To develop this novel technology, Jakobsen founded biotechnology company Avidex Limited in 1999, which was acquired by MediGene in 2006. Two years later, MediGene spun out the TCR technology into two sister companies, Adaptimmune and Immunocore — both of which Jakobsen helped co-found. The former originated as a virtual company through a partnership with the University of Pennsylvania, and was led by two former Avidex employees, James Noble and Helen Tayton-Martin, who co-founded the company with Jakobsen. (Jakobsen served as an advisor for Adaptimmune until 2018, Noble currently serves on the board of directors, and Tayton-Martin is the company’s chief business officer.)

What: Based in the Navy Yard, Adaptimmune is a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company focused on using a patient’s immune system to treat cancer in various solid tumors. Their proprietary T-cell engineering platform, SPEAR (Specific Peptide Enhanced Affinity Receptor), is designed to increase the binding and targeting strength of TCRs, so that they can better locate cancer cells and direct the immune system to the tumor for elimination. In other words, Adaptimmune is genetically engineering TCRs to be specific and deadly for cancer, but not harmful to other cells.

According to Bill Bertrand, the company’s chief operating officer, Adaptimmune employs a “2252” strategic plan. This, he says, involves getting two products approved over the next five years and bringing those onto the market, having two other applications filed for product use, initiating testing on another five products, and moving two next-generation products into the clinic. This approach has allowed Adaptimmune to produce and test multiple SPEAR T-cells. Currently, they have ongoing clinical trials for three of them — afami-cel (formerly ADP-A2M4), ADP-A2M4CD8, and ADP-A2AFP — which address multiple solid tumor indications, including synovial sarcoma and liver cancer.

When: In 2014, Adaptimmune entered a strategic collaboration with GlaxoSmithKline for their initial clinical focus, a SPEAR T-cell therapy program targeting the NY-ESO antigen for synovial sarcoma. (This program was transitioned to GlaxoSmithKline in 2018.) Adaptimmune officially went public in 2015, and two years later, opened their flagship facility in the Navy Yard.

Currently, Adaptimmune’s afami-cel is on track to be the company’s first commercial product. Their investigational new drug (IND) application for the drug was accepted by the FDA in 2017, initiating their Phase I clinical trial and later Phase II. Since then, it has demonstrated effectiveness in synovial sarcoma and other solid tumors, with a recent response rate of 41 percent for the soft-tissue cancer. Adaptimmune says they plan to file afami-cel for FDA approval (for marketing) next year.

What it means: In recent years, a lot of buzz has surrounded CAR-T therapy, which like TCR therapy, modifies patients’ immune cells in order to destroy disease. The difference between the two approaches resides in the binding mechanism. “One limitation [of CAR-T] is that the antibody is artificial and therefore lacks the natural signaling mechanisms of the T-cell receptor (TCR) itself,” says Juli Miller, Adaptimmune’s senior director of investor relations and external communications. “Plus, antibodies are limited to cell surface targets, which becomes an issue in most solid tumors because they lack large protein markers. In fact, cloaking themselves from the immune system is one of the main ways solid tumors thrive and survive — they don’t have big flags on their surface to identify them as cancer.”

While TCRs are responsible for finding disease within actual cells, they still have difficulty targeting cancer cells because their proteins often look “normal,” according to Adaptimmune. The company is designing and working to deliver novel cell therapies that aim to overcome this challenge by harnessing T-cells to attack cancer cells and treat solid tumors.

Why it matters now: According to the National Cancer Institute, synovial sarcoma is a fairly uncommon type of cancer, estimating one to two diagnoses for every one million people per year in the United States. Despite this, synovial sarcoma is often misdiagnosed as benign due to the fact that these soft-tissue malignant tumors are slow to grow and tend not to be painful in early stages. The cancer, which typically develops near a joint in the arm or leg, frequently affects people under the age of 30 and can lead to metastasis if left untreated or is not detected early enough. For this reason, Adaptimmune’s therapeutic afami-cel strives to provide a stronger prognosis and overall quality of life for people living with synovial sarcoma.

But Bertrand says Adaptimmune is also looking to transform the lives of people living with other types of cancer. “In 2020, we provided data that showed responses in six types of solid tumor indications,” he says. “This highlights the potential of our products to help treat cancer types beyond synovial sarcoma, and bring more curative therapies to a wider range of patients.”