Behind the Scenes of the First COVID-19 Vaccination at Einstein Medical Center

An up-close look at what’s hopefully the beginning of the end of the coronavirus pandemic.

On Wednesday, the first COVID-19 vaccination at Einstein Medical Center went to ICU technician Antoine Miller. Photo via Einstein.

Dave Young woke in the middle of the night on Wednesday with a panicked thought: “Oh God, the freezer!” This was the super-cold freezer, the one that was currently holding 1,950 precious doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine at minus-70 degrees Celsius, in advance of the first vaccinations at Einstein Medical Center, set to take place later that day. Young, the hospital’s director of pharmacy services, had a sudden fear that the freezer had gotten too warm and the vaccine was in danger of spoiling. He got up in the middle of the night to check the temperature from his computer. Everything was fine: The super-cold freezer was indeed super-cold.

Divorced from context, there was nothing much to be stressed about. Administering a vaccine is to pharmacology what dribbling is to basketball — the kind of basic action that becomes second nature to the point that you basically can’t screw it up. But it’s hard to escape the context: Young was delivering the very first doses of a vaccine to a hospital staff that had been through a terrible spring — a terrible year, really — confronting PPE shortages and a pandemic that, 10 months in, continues to spread. There were just 1,950 doses to go around — too few to vaccinate the roughly 4,500 employees at the hospital, and thus no room for error. Yes, you could say Young was feeling the pressure. “It’s like when they interview somebody before the Stanley Cup and they say, ‘Oh, it’s just another game,’” he said. “It’s certainly not just another game, and it’s not just another day for us.”

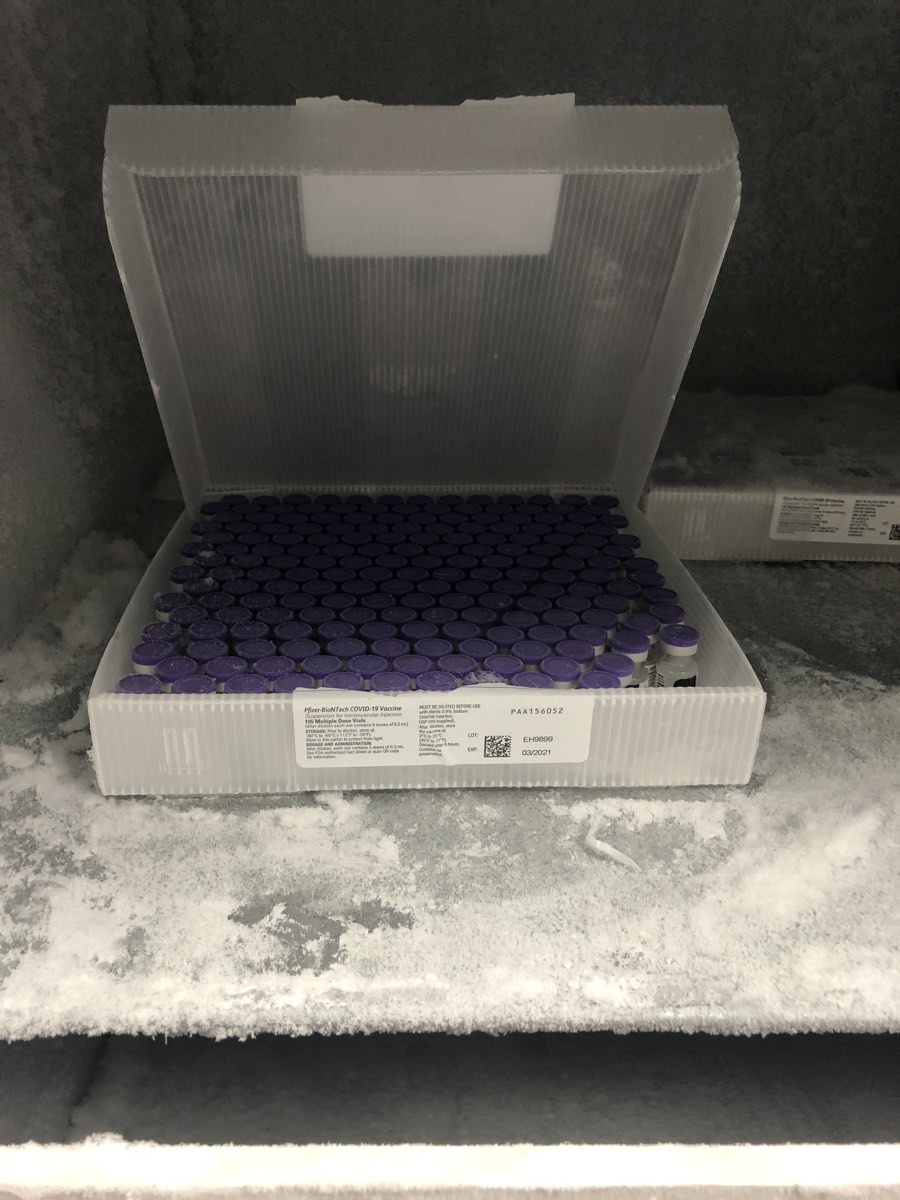

One reason for the anxiety was that the Pfizer vaccine is finicky. “In my 22 years of pharmacy, we’ve never needed to use a super-cold freezer for anything before,” Young said. The vaccine can’t get above minus-60 degrees Celsius, which means the freezer door can only ever be open for three minutes at a time. Young had installed a thermometer that provided temperature readings every five minutes — readings that remained perpetually open on his computer screen.

A so-called “pizza box” filled with the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine. Photo by David Murrell.

Once the vaccine is out of the freezer, a different countdown begins: It has to be diluted with saline solution within two hours of being thawed, and it has to be used within six hours after that. Vaccinating 100 people over a 12-hour window, as Einstein was, presented logistical challenges: When to first take the vaccine out to thaw? When to dilute it with saline? And how many vials to remove at once to make sure you get through them all within the deadline?

This was all going through Young’s head as he tried and failed to sleep on Wednesday morning. By 6:55 a.m., he was in the office, unlocking the two padlocks on the freezer and reaching into a frost-covered white cabinet to grab the “pizza box” — a nine-by-nine-inch plastic box filled with rows of tiny glass vials topped with purple caps. He removed 10 vials, enough for 50 doses, and after they thawed took an elevator down to the pharmacy lab, where at 7:35 a.m. he deputized another pharmacist, Bhaskar Sundaram, to dilute the vaccine. This, too, was routine. Still, Young peered through a glass window to make sure nothing went wrong.

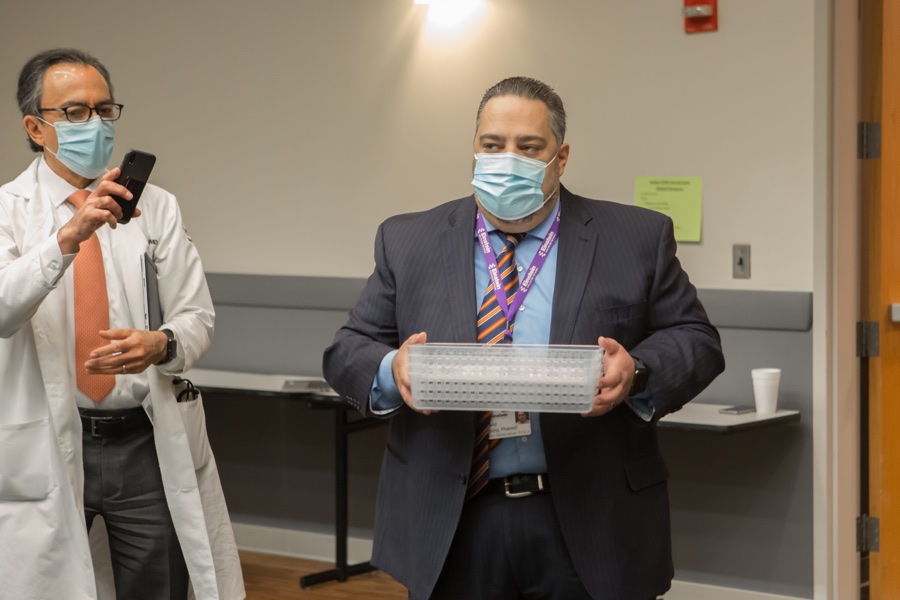

Now the vaccine was ready. Young carried it to the vaccine clinic on the other side of the hospital, the plastic box just below his chest as if he was presenting some kind of sacred offering.

Pharmacist Dave Young carries 50 doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine. Photo courtesy of Einstein.

A few minutes after 8 a.m., Antoine Miller, a soft-spoken 37-year-old ICU technician, rolled up his left sleeve. As a nurse stuck his shoulder with a needle, Miller made a bit of history: He became the first person at Einstein to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, and among the first in all of Philadelphia.

Miller, like some of the other health-care workers who opted to receive the vaccine, still had reservations; he was fearful that it had been approved too soon. Side effects had been exceedingly rare, although two patients in England went into anaphylactic shock after receiving the vaccine just this week, and two more health-care workers in Alaska would end up experiencing allergic reactions that day. A nurse anesthetist was on hand at Einstein with a stretcher, a wheelchair, and a pulse oximeter, just in case.

But Miller felt the benefits outweighed any fears, as did most of Einstein’s staff, 71 percent of whom said they wanted the vaccine. Miller’s job in the ICU, which can involve turning COVID-19 patients onto their stomachs to help them breathe, is particularly risky — all the more so because he has asthma. At the beginning of the pandemic, his doctor recommended he stay home from work. “But I couldn’t afford to, so I had to be here,” Miller explained.

With a prick of the skin and a push of a nurse’s thumb on a syringe, he was vaccinated. A group of doctors and hospital administrators looked on and snapped photos. There was a brief cheer. The whole thing was over in a matter of seconds. For all of the buildup — the billions of dollars invested, the angst and fear of the past 10 months — the moment was something of an anticlimax.

After the shot, Miller stood up and posed for the cameras, making a peace sign, his white N95 mask covering his face. “You’re famous now,” said one of the doctors looking on. “Don’t forget to smile.”