How a New App Could Help Prevent Opioid Overdoses in Philadelphia

Researchers at Drexel University, who put the UnityPhilly app to the test in Kensington, now have plans to introduce the program citywide.

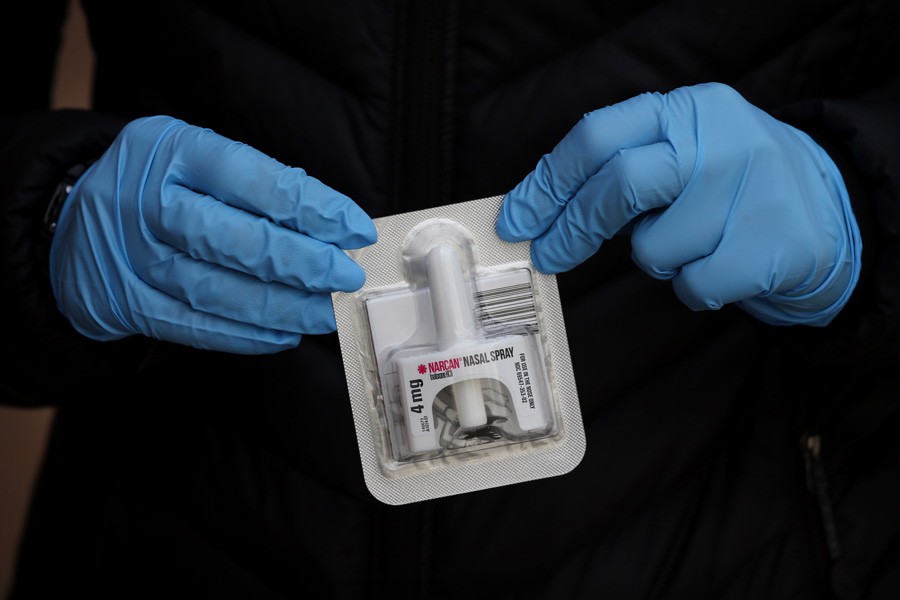

The UnityPhilly app is working to get noxolone more quickly to those who need it. Photograph by Boston Globe/Contributor/Getty Images

When the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in the region, Philadelphia was already grappling with a public health crisis: the opioid epidemic. In 2019 alone, there were 1,150 drug overdose deaths in Philadelphia, and 84 percent of those overdose deaths were caused by opioid use. Philadelphia still has the highest per capita overdose mortality rate among large U.S. cities and growing reports suggest drug overdoses in the region have not slowed.

A team of researchers at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health has developed an app that they believe will help address the opioid crisis in Philly, even while most resources are being deployed to address COVID-19. The researchers worked with a team of developers to create an app called UnityPhilly that helps community members signal overdoses in progress in real-time to nearby volunteers who can administer naloxone, an opioid overdose-reversing medication.

Last year, the researchers put the concept to the test by launching a study using the app in the Kensington community, the Philly neighborhood that accounted for the highest number of overdose deaths in 2019.

Stephen Lankenau, the associate dean for research and a professor in the department of Community Health and Prevention at Drexel, led the study in which his team recruited 112 participants from the Kensington community, half of whom were active opioid users and the other half of whom were in recovery from opioid use or had experience working with opioid users and were willing to respond to an overdose. All participants in the study received the app on their phone and were trained on how to use it. And then, as Lankenau explained, “They just kind of went on their way.”

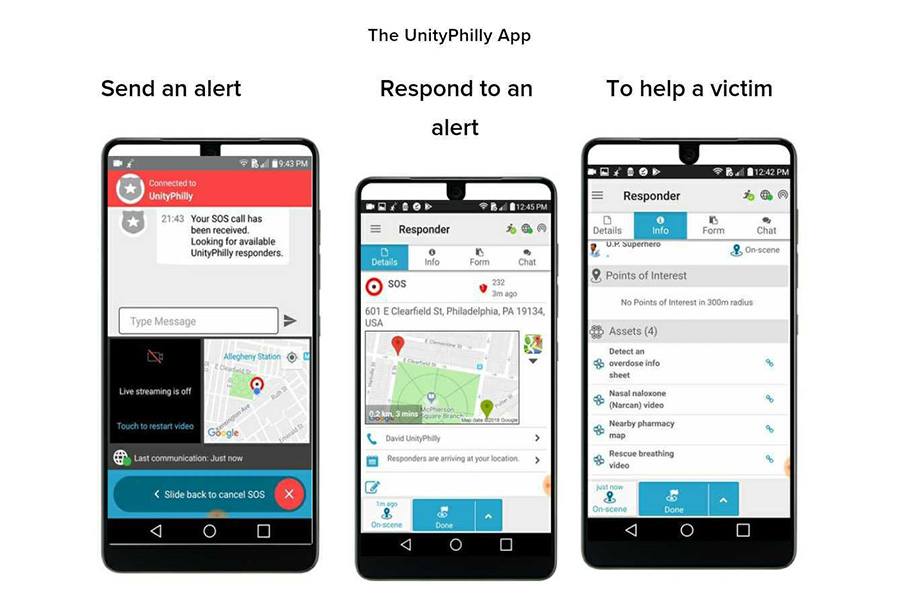

A closer look at the UnityPhilly app. Image courtesy UnityPhilly

The app only prompts action when a participant sees an overdose in progress.

“Once someone has the app on their phone, if they were to see an overdose, they could pull out the app and signal an overdose on their phone,” Lankenau explained.

“That alert would then go out to everybody within a several block radius of where they were in Kensington, and if someone received the alert, they would then indicate whether they were able to respond.”

From there, the app provides the responder with the address and location of the overdose so the responder can walk or drive to that location and provide naloxone to the person who is overdosing.

According to Lankenau, the app addresses the critical issue of informing someone who can help when an overdose is in progress — before it’s too late.

“Overdose prevention training and naloxone distribution have been around now for quite some time, so the idea of responding to an overdose was not novel to most participants; many of them had rescued and saved people previously,” he explained.

“What’s new, that the app helps enable, is the possibility for community members to learn about an overdose and respond to it in real-time. Without the app, there could be an overdose happening around the corner that they couldn’t see. So, the app presents a new way to inform people that there is an overdose in process and to help them get to that location.”

Lankenau’s team found that the app led to a successful reversal of overdose in 95.9 percent or 71 out of 74 cases reported through the app. In over half of these incidents, study participants administered naloxone more than five minutes faster than Emergency Medical Services (EMS) were able to arrive on the scene.

Jeanmarie Perrone, a founding director of the Penn Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, says response time in opioid overdose situations is critical.

Perrone has had her own share of experiences intervening to prevent opioid overdose deaths, including a harrowing incident on a Philadelphia subway train that drove her and other strangers to spring into action, administering Narcan and CPR to save a life when a fellow rider overdosed.

“It was a great lesson for me about carrying Narcan all the time and recognizing that it really is all of our civic responsibility to help in these situations,” Perrone said.

Incidents like these, Perrone says, make a case for the importance of apps like UnityPhilly to be used more broadly in communities that need it most.

“I think it’s an outstanding opportunity to make sure that people who are in the community at risk can get access to Narcan or naloxone if they need it,” she said. “I love the idea of the app and I think it’s likely to work in an area where the prevalence of substance use is high.”

Having seen success in Kensington, Lankenau’s team is now making plans to roll out the program citywide, despite the prevalence of COVID-19 in the region. Lankenau says preliminary surveys with past participants in the program found most responders would be willing to continue participating in the program and responding to overdoses if COVID-related safety precautions were in place.

“We’re in the process of developing another research proposal to try to expand this to multiple neighborhoods across the city to see if we could get, instead of hundreds, thousands of people using the app in communities across the city,” Lankenau said.

If the group is able to secure funding this year, the app could be rolled out to additional Philly neighborhoods before the end of 2021.