NextUp: Larimar Therapeutics Is Advancing Clinical Trials for Complex Rare Diseases

Amid a widespread freeze of clinical research due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this local company has continued progress toward a potential cure for Friedreich’s ataxia (FA).

Carole Ben-Maimon is the president and chief executive officer of Larimar Therapeutics. / Courtesy

“NextUp” is a weekly NextHealth PHL feature that highlights the local leaders, organizations and research shaping the Greater Philadelphia region’s life sciences ecosystem. Email qmuse@phillymag.com with pitches for NextUp.

Who: Over the past 30 years, Carole Ben-Maimon has worked for several science companies, helping them formalize their clinical research efforts. But Ben-Maimon is a physician first and it was her background as a nephrologist that piqued her interest in leading an effort that could help treat Friedreich’s ataxia (FA), a disease that Ben-Maimon says is nothing short of devastating for the children who inherit it.

“Kids with FA are born looking healthy and by puberty, they are falling and losing their balance and can’t do what they had originally been able to do,” Ben-Maimon explained. “They’re in wheelchairs by their 20s and many of them die in their 30s and 40s or have lost their ability to walk or talk; many of them go blind or deaf. It’s really an incredibly debilitating disease.”

In 2016, Ben-Maimon assumed the role as the chief executive officer of Chondrial Therapeutics, a local biotech company whose pipeline focused exclusively on developing treatments for FA and other mitochondrial disorders that are difficult to treat. Earlier this year, Chondrial merged with the publicly-traded biotech company, Zafgen, and began operating under the name Larimar Therapeutics.

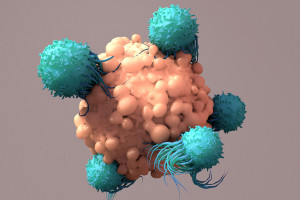

What: Friedreich’s ataxia is the most common form of hereditary ataxia — a genetic disease that disrupts the central nervous system, causing progressive incoordination — in the United States; it affects roughly one in every 50,000 people. There is currently no cure or effective treatment for FA. The disease is caused by a deficiency of the mitochondrial protein, frataxin (FXN), which is found in cells throughout the body. According to Ben-Maimon, that’s what makes FA such a uniquely challenging disease to treat.

“The protein works inside the mitochondria of the cell,” she explained. “To treat it, you have to get the protein across the cell membrane and across the mitochondrial membrane, which is a challenge.”

Using a technology developed by R. Mark Payne at Indiana University School of Medicine, Larimar Therapeutics has launched a Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the safety and tolerability of CTI-1601, a recombinant fusion protein intended to deliver human frataxin to patients with FA.

“There are very few neurodegenerative diseases where you actually know the problem and know what the cause is. With FA, we know what the cause is, and we now have what could potentially be a solution,” Ben-Maimon said.

Because the technology has the ability to cross the cell membrane, in the future, it could also be applied to a host of other rare diseases that require a protein or other curative cargo to be delivered into a cell.

When: Larimar originally launched its double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for FA patients in December 2019 and had dosed two cohorts of participants before the pandemic forced the company to temporarily halt the trial in mid-March.

What it means: Larimar’s trial patients were being housed in an independent research unit in New Jersey. In the early days of the pandemic, many of the participants were coming from all over the country to New Jersey to participate in the trial. At the time, very little was known about how the virus was spreading. Once it became apparent that the trial would be too dangerous to continue while COVID-19 was steadily spreading throughout the country, Ben-Maimon made the tough decision to halt the FA trial while the company worked to identify ways to resume the trial safely.

“Obviously, the safety of the patients is the most important thing for all of us. So, we put it on hold; we followed all the news and information that was coming out of CDC, and we focused on making the experience safe for the patient,” she said.

Larimar started by requiring trial participants to undergo COVID testing at home and to quarantine for two weeks before coming to the research unit. They also made sure patients had limited opportunity for exposure to COVID during their trip to the research site by requiring them to drive to the site themselves or fly in privately and limited contact with other people (once they arrived at the research unit, they were not allowed to leave until dosing was complete). The company’s research site was also outfitted with all the necessary capabilities and protocols, including being able to test participants for COVID-19 and to isolate any presumed positive cases.

Once implemented, these changes combined enabled Larimar to resume the trial and begin dosing its third trial cohort in late July. The company expects to have topline results from the trial in the first half of 2021.

Why it matters now: Larimar is not alone. More than 1,600 clinical trials, worldwide have been discontinued or temporarily stalled due to the pandemic. For the foreseeable future, researchers around the globe will be taking notes from one another on how to overcome new challenges in conducting clinical research in a pandemic.

Ben-Maimon says her company was fortunate to be conducting a cohort study where trial participants are dosed in a confined setting, monitored for a period of time, and then sent back to their homes intermittently. It’s a lot harder for researchers who are giving drug doses to patients every month or every three months, as most clinical trials at large academic medical centers require.

“That’s a lot more challenging,” Ben-Maimon said. “But clinical research is essential. It’s critical to advancing and finding cures and treatments for people of all walks of life with all diseases. So, I think we’re all going to have to make some benefit/risk assessments and do everything we can to protect the people participating in these trials so we can continue to move these cures forward.”