An Inside Look at Penn’s Brain-Zapping Treatment for Essential Tremor

MR-guided focused ultrasound therapy is now covered by Medicare, giving millions of patients access to a minimally invasive treatment for the world’s most common movement disorder.

Ellen Gruebel is one of an estimated 10 million Americans living with essential tremor, a neurological condition that causes uncontrollable shaking in various parts of the body. / Courtesy

For roughly 20 years, Ellen Gruebel has been unable to apply her own make-up, cook and eat her favorite meals or sign her name. Pouring coffee was out of the question. All these daily activities were complicated by the unrelenting involuntary shaking in her hands.

“When I’d flip a burger or an egg in the frying pan, I’d have to use two spatulas; eating certain foods was almost impossible. Eggs would always fall off my fork or half the soup would be off the spoon by the time it would get to my mouth, and putting on eyeliner or mascara, I’d have to use both hands and get right up in front of the mirror to try not to poke myself in the eye,” Gruebel said. “It was very frustrating not being able to do the little things that we sometimes take for granted.”

Gruebel, 69, is one of an estimated 10 million Americans living with essential tremor, a neurological condition that causes shaking in various parts of the body; most often, in the hands. It runs in families; Gruebel’s mother, aunt and brother all had it at some point in their lives. It’s the most common of all movement disorders in adults. Yet, despite its prevalence, there is no specific medication for essential tremor, and until recently, the only treatment option available was deep brain stimulation, an invasive surgery that involves implanting a pacemaker-like device in the chest that sends electrical signals through a wire under the skin and up to brain areas responsible for body movement.

For two decades, Gruebel has maintained a daily routine of taking high-dose beta-blockers and anticonvulsants, medicines that helped tame but not cure her tremor. In July, she became one of the first patients in Pennsylvania to receive MR-guided focus ultrasound therapy, a relatively new treatment for essential tremor, available at Penn Medicine.

Penn is one of only 22 centers in the U.S. and the only hospital in the state that offers the treatment. Gruebel has known about focused ultrasound therapy since 2016, shortly before it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a viable treatment for essential tremor. But the cost of the procedure, estimated between $20,000 and $40,000 depending on insurance coverage, was prohibitive. This meant Gruebel would have to endure yet another long wait until the procedure became more affordable either through decreases in the pricing of the procedure or coverage by government health insurance.

On July 15th, Gruebel’s wait finally came to an end when MR-guided focused ultrasound therapy for essential tremor was approved for Medicare coverage across all 50 states, substantially decreasing out-of-pocket costs of the procedure for Gruebel and as many as 40 million other Medicare recipients. At Penn, the procedure would cost $30,000, but now Medicare would cover 80 to 100 percent of that total.

Though Gruebel was on a long waitlist of over 150 patients who’d previously signed up to receive the treatment at Penn, due to cancellations related to the pandemic, she wound up being one of the first people called in to receive the treatment. Never mind that she’d have to travel over 120 miles to Philadelphia from her home in Maryland or that she’d undergo the procedure in unprecedented pandemic conditions; Gruebel was ready to get rid of her tremor once and for all.

MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound Therapy

Ellen Gruebel and her neurosurgeon, Gordon Baltuch, pose for a photo before her MR-guided focused ultrasound procedure begins. / Courtesy

On July 15th, Gruebel journeyed to Pennsylvania Hospital to receive her treatment. Her procedure would be performed by a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, neurosurgeons and radiologists under the leadership of the director of Penn’s Center for Functional and Restorative Neurosurgery, Gordon Baltuch. Before focused ultrasound became an option for essential tremor, Baltuch performed more than 1,500 deep brain stimulation surgeries. He’s since performed 75 focused ultrasound procedures.

Gruebel had already undergone hours of pre-operative testing days before. Now, came one of the least appealing stipulations of the procedure: Gruebel would have to have her head shaved completely bald.

MR-guided focused ultrasound requires tremendous precision. That begins with doctors shaving the patient’s head to make sure it’s free of hair, scar tissue or anything that might obstruct the ultrasound waves.

“I wasn’t happy about that, but I really wanted this procedure for years,” Gruebel said. “It was one of those things that I just accepted.”

In the ‘operating room,’ Gruebel received local anesthesia before doctors affixed a helmet-like structure to her shaved head using two pins above the edges of her eyebrows to hold her head completely still during the procedure. One false move could result in permanent damage to critical cells in Gruebel’s brain.

Baltuch and his team sit at the console from which the targeting and high frequency focused ultrasound therapy are delivered. / Courtesy

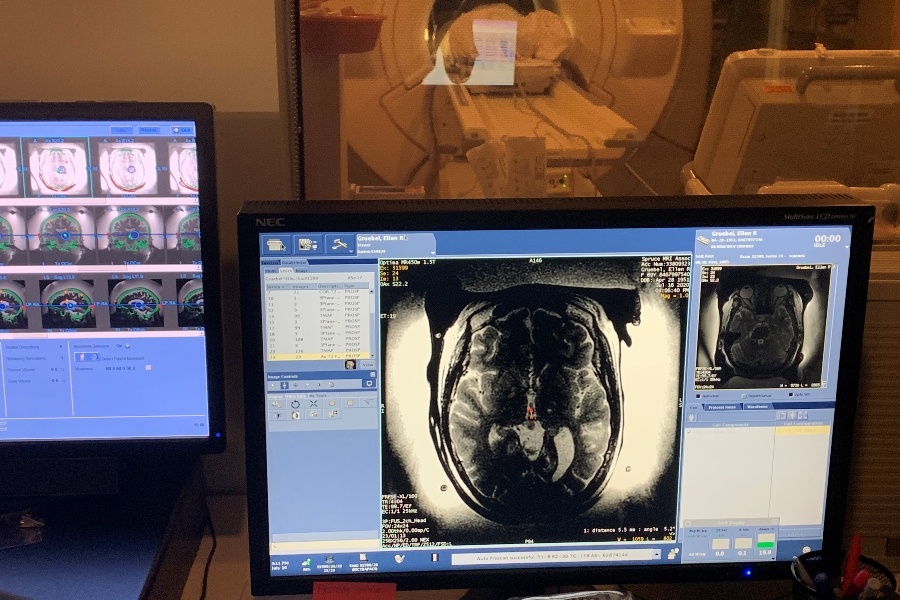

The procedure itself is done in an MRI unit without general anesthesia and sedatives, meaning Gruebel was awake and alert as, over the course of roughly three hours, doctors used real-time MRI imaging to deliver a series of low-power “sonications” to test the accuracy of the targeted location in the brain followed by high-frequency (104–113°F) ultrasound waves to zap target cells in the center of the thalamus, a part of the brain responsible for relaying sensory and motor signals.

Here, Gruebel lies in the MRI machine in a room adjacent the console from which the targeting and high frequency focused ultrasound therapy are delivered. / Courtesy

According to Baltuch, even the shape and density of the skull plays a role in the success of the treatment. Gruebel’s case was unique because she has a low skull density ratio.

“Her having a low skull density ratio (SDR) would technically make her case much more difficult because the skull is going to absorb a lot of the soundwaves, making it hard for those waves to get to the target,” Baltuch explained. “However, we now know that it’s not only SDR but skull shape that is important as well. So, while we used to focus on getting to a certain temperature in order to make a lesion, we’ve now learned that with SDR cases, it can be just as effective, if not even more effective to create a lesion by going to a lower temperature, but for a longer period of time. So, that’s what we did with Ellen.”

At various points in the procedure, Baltuch’s team paused to have Gruebel hold a cup of water. This allowed them to see whether they’d made a big enough lesion in the thalamus to calm her tremor.

At various points in the procedure, after each ultrasound zap, Baltuch’s team paused to have Gruebel hold a cup of water and ask how she was feeling. This allowed them to see whether they’d made a big enough lesion in the thalamus to calm her tremor. In Gruebel’s case, the team had to pause four times to assess her tremor and adjust the temperature of each subsequent zap accordingly.

Before the procedure, Gruebel’s shaky dominant hand produced visibly jagged lines in the spiral. Afterward, her handwriting was almost completely smooth. / Courtesy

The team also did a pre- and post-procedure analysis of Gruebel’s handwriting called the spiral test. Before the procedure, Gruebel’s shaky dominant hand produced visibly jagged lines in the spiral. Afterward, her drawing was almost completely smooth. In the post-op room, she held and drank from a full cup of water. None of it spilled.

“You come out of the procedure and your hand is steady. It’s immediate,” she said. “They sat me up. They took the helmet off my head. I looked at my hand and I started to cry. I was just so ecstatic because it’s life-changing to suddenly be able to do simple things again.”

In the post-op room, Gruebel held and drank from a full cup of water. None of it spilled. / Courtesy

Because the procedure did not require any incisions, Gruebel was able to go home the same day. The next morning, she conquered a long-awaited feat.

“I flipped my grilled cheese sandwich with one spatula for the first time in many, many years. It was a great moment for me.”

Bi-lateral Treatment

Ellen Gruebel is one of an estimated 10 million Americans living with essential tremor, a neurological condition that causes uncontrollable shaking in various parts of the body / Courtesy

Like many people who have essential tremor, Gruebel had a tremor in both hands. Focused ultrasound eliminated the tremor in her dominant right hand but her left hand still shakes. Even though it would mean having her head shaved all over again, Gruebel said she’s open to having the procedure done again to alleviate the tremor in her non-dominant left hand.

Baltuch said he understands why patients often ask to have the procedure done in both hands because, “There are a bunch of things where you actually need two hands to function,” like holding an iPad still with one hand and swiping the screen with the other or, as one of Baltuch’s patients once told him, “You try unbuttoning your shirt with one hand and then ask me why I want to get the other hand done.”

But a few hurdles stand in Gruebel’s way.

MR-guided focused ultrasound is currently only approved by the FDA for treatment in one hand. According to Baltuch, before the first approval, FDA officials were scrutinous of the treatment because they wanted to make sure it “was not some procedure that worked for just a few months and then came back.” It took more than seven years for researchers to gather enough data to demonstrate the good, long term effects of the treatment. An approval for bi-lateral treatment would probably take just as long to attain, not to mention the expected wait for the procedure to be covered by Medicare and major health insurance carriers.

Baltuch says his team is in the process of launching a clinical trial to begin gathering data that might prove it’s safe to have the treatment done in both hands. Gruebel says she’ll be standing by.

“I might want to come back and go through this again,” Gruebel said. “It depends on how old I am when or if Medicare approves it. If I’m still alive, I’d be open to it.”