NextUp: The Philly Brain Researcher Working to Eliminate HIV

Temple University professor Kamel Khalili has been researching HIV for more than 20 years and just got one step closer to finding a cure.

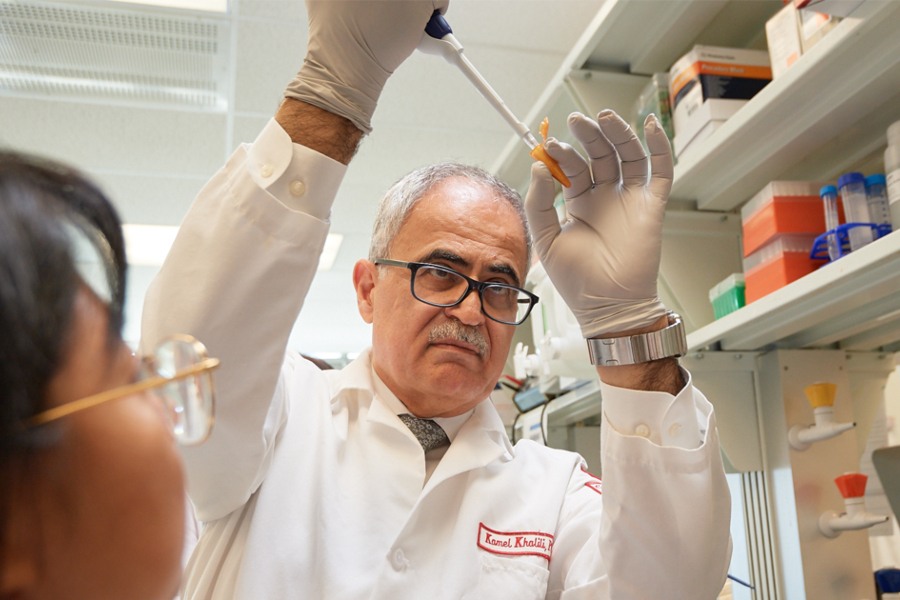

Temple University professor Kamel Khalili working in the lab.

“NextUp” is a weekly NextHealth PHL feature that highlights the local leaders, organizations and research shaping the Greater Philadelphia region’s life sciences ecosystem. Email qmuse@phillymag.com with pitches for NextUp.

Who: Kamel Khalili serves as the Laura H. Carnell professor and chair of the department of neuroscience, director of the Center for Neurovirology, and director of the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University (LKSOM). His medical career began at the University of Pennsylvania where he studied molecular biology. Over the past 40 years, he’s conducted research and taught for several local institutions, including the Wistar Institute, Thomas Jefferson University, Hahnemann Hospital, and for the last 20 years, Temple University. But it was the three years he spent working as a Fogarty Scholar with the National Cancer Institute in the National Institutes of Health that led him to focus on studying the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

“The start of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, as a biologist, it was very fascinating but at the same time it was very depressing to see this widespread infection taking a toll on so many people,” Khalili told NextHealth PHL. “That’s when I knew I wanted to start working on HIV and other viruses that affect the brain.”

What: HIV is a major infectious disease that can lead to spinal cord and brain damage, as well as nerve cell dysfunction. Even though HIV is not a hereditary disease, it does live and replicate in DNA. Khalili believes he and a team of fellow researchers are on the verge of eliminating the virus through the use of genetic-based interventions.

When: In July, Khalili and a team of interdisciplinary researchers released the results of a study that showed the group had successfully removed the HIV virus from the genomes of mice. The researchers used CRISPR-based gene editing technology combined with long-acting slow-effective release antiviral therapy (LASER ART), a new antiretroviral treatment.

“Our study shows that treatment to suppress HIV replication and gene editing therapy, when given sequentially, can eliminate HIV from cells and organs of infected animals,” said Khalili, a senior investigator on the new study.

Khalili’s team is currently working to apply the same method in a study of large animals with hopes of gaining FDA approval to move forward with Phase I clinical trials in humans as early as next summer. Khalili says he founded Excision BioTherapeutics, a Philadelphia-based company that uses gene editing tools to treat infectious diseases, to raise money for future clinical trials and to support the commercialization of this new HIV treatment method.

Why: According to UNAIDS, a global effort to end acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), since the first cases of HIV were reported more than 35 years ago, 78 million people have become infected with HIV. Nearly half of those individuals have since died.

Many of the more than 36 million people living with the disease today are limited to taking one or more of the 24 FDA-approved antiretroviral treatments for life. Khalili says these treatments control the growth of the virus but do not eliminate the disease; anytime the patient stops taking antiretroviral medications the virus can rebound putting the patient at risk of developing AIDS. It’s also worth noting that not all patients can afford antiretroviral treatments, and others may experience unwelcome side-effects.

What It Means: Here in Philadelphia, more than 19,000 people are living with HIV, according to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. The city sees anywhere from 500 to 700 new cases of HIV infections each year. As recent as 2014, Philadelphia’s HIV infection rate was five times the national average.

There is currently no cure or vaccine for the disease.

“Our study is the first proof that HIV can be cured. Altogether, our research showed that out of 23 animals nine of them became completely virus-free,” Khalili explained. “I think it’s a very good milestone considering that nothing on the market right now can make the virus disappear permanently.”