La Baja Is Chef Dionicio Jiménez’s Best Cooking Yet

Scallops and chorizo meet Thai curry; hibiscus-braised short rib mingles with risotto — the menu at La Baja is a chimera of culinary influences.

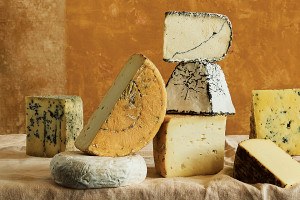

Carnitas de pato and ravioles de aguacate con cangrejo from La Baja / Photography by Breanne Furlong

On a freezing night in Ambler, deep in the post-holiday slump, I slide alone into a two-top table at Dionicio Jiménez’s new restaurant to eat roasted baby beets sprinkled with pistachios in a homemade crema called jocoque — brought to Mexico by Lebanese people fleeing the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century — and a chile relleno stuffed with scallops and chorizo under a blanket of melted queso asadero and swimming in a pool of Thai green curry. On the wall above me, there’s a sculpture that I love. It’s big, garish, weird — an elephant head with blue butterfly wings and an octopus body, arms writhing against the whitewashed brick in the main dining room.

Chef Dionicio Jiménez at La Baja

It’s an alebrije, a mystical creature — dreamy and powerful, heavy with portent. And I like it because it is a thing made from pieces of other things — the wings of a monarch butterfly, strong enough to survive migrating across half the world; the head of a wise elephant; and those squirming, adaptable arms. There’s meaning there. A history encapsulated in dream logic and bright lacquer paint because Jiménez, of course, is his own kind of alebrije — a chimera who came to the States in his 20s from Mexico, crossing the border on foot, then finding his way into the kitchens of Vetri, Solomonov, and Starr. Decades in the industry taught him to be an octopus — to adapt, to do eight things at once. And when the time came for him to go his own way, he opened Cantina La Martina in the heart of Kensington, under the El, and gained national recognition for his Mexican cuisine twined with this hot thread of every other thing he’d learned to cook and eat and love along the way.

La Baja is a further distillation of that impulse — no longer chasing the dragon of “authenticity,” he does a cuisine here born of every shift he’s worked, every post he’s stood in a dozen different kitchens.

Jiménez has a carnitas de pato entrée on his menu — a whole roasted duck with bao buns, jicama salad, and nopales — that I will probably never get to taste because I am a fundamentally chaotic human and can never get my shit together enough to order it three days in advance, as required, but that’s fine. I can comfort myself with bok choy sautéed with salsa macha and elote corn ribs, cut deep into the cob, that accordion open when you bend them, allowing you to strip away the charred kernels dressed in preserved lemon, grated cheese, and tan tan dust (used to amp the heat in spicy ramen).

Prawns with mole verde

Another night, under the calm gaze of La Baja’s bright butterfly octophant, I roll in with friends for the special — big-ass prawns curled in a puddle of unbelievably good and gentle green mole, white rice, and an arugula salad topped with slivered red onion and trout roe. It’s on the board as an entrée, but I have my eye on other things, so I ask the server (alone on the floor on a night that’s worryingly quiet) if we can split it as an app — one plate for the pair of us.

“Sure,” she says. “Honestly, that’s kind of a pro move.” And she’s right, because we load down the table with plates of prawns in mole; ravioles made of fanned avocado and stuffed with blue crab, lardons, and a xnipec salsa that’s all sweet habanero heat and a razor of vinegar brightness; fists of short rib, braised in hibiscus and Mexican chocolate and mounted atop a bowl of creamy Italian risotto; and perfect pork belly, seared crisp and served between two quenelles of sweet potato puree like a remembered taste of Thanksgivings past. We eat for an hour, maybe two. By the time we leave, there are still only two other tables with guests in the dining room.

Braised short rib over risotto

Once upon a time, I said that the best thing about Cantina La Martina was that everything you eat there is something you know — just the best version of it you’ve ever had. But La Baja is not Cantina. It is not Vetri or Xochitl or El Rey, a late-night ramen shop or Chinatown or bland frontera fusion or anything else either. It is its own thing. Its own alebrije — a combination of decades of study and influence, all coming together as a pure expression of singular identity. It’s not like anything you’ve had before.

But it may be the best version of Dionicio Jiménez’s cuisine yet.

Published as “The Alebrije of Ambler” in the March 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.