What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About the Michelin Guide

Would Michelin’s presence threaten the spirit of Philadelphia’s dining scene, or help it? Who would really benefit?

The Michelin Man attending the release party for New York City’s Michelin Guide. Should Philadelphia be next? / Photograph by Scott Wintrow/Getty Images For Michelin

Kiki Aranita is a food writer, former Classics scholar, and the owner of Poi Dog Sauces, a company that grew out of her former Center City restaurant, Poi Dog, after it closed during the pandemic.

The question of whether or not we should have a Michelin Guide feels like another battle in the war on what kind of city Philly should become. Do we want to continue nurturing our diverse and spunky dining scene? Or do we invite Michelin to rate Philadelphia’s restaurants and risk creating the world-class “creeping sameness” that has started to blanket other cities?

The Michelin Guide is a series of guidebooks dedicated to a city’s restaurants. It’s published by the French tire company Michelin and obtaining a star rating (1 through 3 — the more stars, the better) is frequently considered the most prestigious honor a restaurant can receive. The term “Michelin” is frequently misused, as stars can only be bestowed on restaurants, not chefs. Its newer Bib Gourmand category identifies restaurants that are of good value, but aren’t necessarily serving “boundary-pushing cuisine.”

The only reason we’re even having this conversation is because of the independent chefs and restaurateurs who make Philadelphia’s dining scene what it is. We’re bold, ambitious, incredibly talented and wildly creative, and it shows with all of the national accolades and splashy coverage. (The New York Times’ 2024 food trend predictions says Philadelphia will be seen “as a food town.”)

But Michelin’s presence could perpetuate an endless cycle in Philly: Fancier restaurants would get fancier while smaller spots wouldn’t be able to compete … because they can’t afford the liquor licenses … which would help them make more money … which would give them a leg up with Michelin inspectors … which may earn them some stars … which may help them make more money.

Philadelphia James Beard award winners Chutatip “Nok” Suntaranon of Kalaya with Mike Prince, Hanna and Chad Williams of Friday Saturday Sunday, and Ellen Yin of Fork / Photographs via Getty Images

In 2023, Philadelphia won more James Beard Awards than any other city in the country. So the next logical step is a Michelin Guide, right? It would make sense given our geographic proximity to New York City, which got its guide in 2005, and Washington D.C., which got one in 2016. (I was in Washington D.C. in 2019 for the unveiling of stars at the French Ambassador’s Residence. It was very exciting.) But in this speculation there are two myths.

Myths are not necessarily falsehoods, but they are stories that we tell one another to explain phenomena that we cannot comprehend. When the Archaic Greeks tried to explain to themselves the creation of the cosmos, they fabricated deities sprung from Chaos. When Philadelphians try to explain to themselves the absence of Michelin, we treat Michelin like a deity, struggling to understand their almost unknowable methods.

But what if there are no deities in either case? What if, like the Archaic Greeks, we’re deifying figures that do not exist and making assumptions based on smoke, mirrors, and (Michelin) Stars?

Myth one: Philadelphia’s restaurant scene is incredible, and we’re being snubbed by Michelin.

For the first century of Michelin Guide’s existence, the expensive endeavor of sending inspectors to rate restaurants around the world was funded by the sales of their annually published guidebooks. Even when Michelin first came to the United States in 2005 to rate New York City’s restaurants and returned in 2007 to create guides for San Francisco Bay and Napa Valley, Michelin didn’t accept sponsors. But in 2019 when Visit California paid Michelin $600,000 to do a statewide guide, Michelin’s attention seemed to shift. Though restaurants can’t buy stars, and paying Michelin only gets tourism boards the “possibility” of a guide according to the New York Times, we’ve seen more and more cities and states strike deals with the franchise.

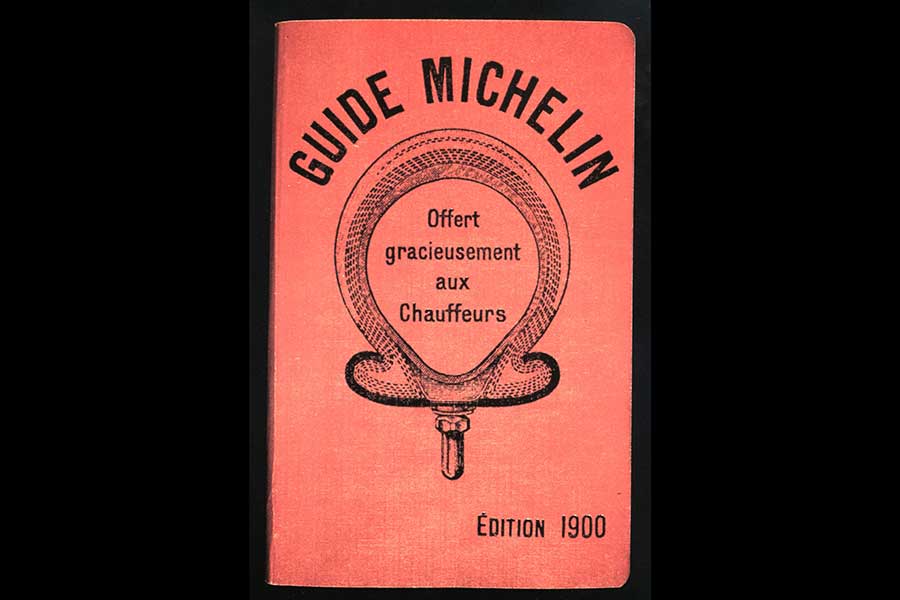

The first Michelin Guide was published in 1900 / Photograph by Apic/Getty Images

Visit Florida worked with local tourism boards in Miami, Orlando, and Tampa, and paid $1.5 million over three years to bring a guide into existence. The practice is also international, as tourism boards from Hong Kong to South Korea and Thailand paid Michelin to review their food scenes. We have also seen these partnerships fall through, as they have in Boston after Dave O’Donnell, MeetBoston’s vice president of communications, learned that it was pay-to-play. The MeetBoston team also noted that, because Michelin seems to favor high-end Eurocentric and Japanese restaurants in the United States, it would be a massive investment that would only highlight a small subset of their city’s dining scene.

Why pay for marketing ploys like Michelin when we already have the attention of the James Beard Foundation? Well, Michelin is an internationally recognized brand. When I was nominated for a James Beard Foundation media award in 2022 and told my family in Hong Kong, a city with 77 Michelin-starred restaurants, they asked, “What’s that?”

My Hong Kong family knows what Michelin is because of the strength of that designer brand. Michelin has an almost immeasurable international cache, and it brings international culinary tourists to destinations with starred restaurants in ways that no other entity can.

The JBF is merely national, and though effective in highlighting some restaurants, it has different goals than Michelin. The JBF is a non-profit and its mission is to “celebrate, support, and elevate the people behind America’s food culture and champion a standard of good food anchored in talent, equity, and sustainability.” Michelin is for-profit and its mission is to sell a lot of tires.

The JBF intends to serve restaurants. Michelin serves diners.

Philly’s 2023 James Beard Award Winners being celebrated at Visit Philly event. / Photograph by Kae Lani Palmisano

Let’s presume that one of our tourism agencies would have to pay in the ballpark of $500,000 to lure Michelin into rating our restaurants. To put it into a Philadelphia restaurateur’s perspective, that is the cost of two liquor licenses (which I’ll get to in a moment). It could be worth it considering Michelin is a designer brand with international cache that would bring more recognition to Philadelphia’s dining scene (and give opportunities to chefs like me to gain experience and eventually, qualify for jobs asking for chefs with “Michelin Star experience”). But it would only really benefit a certain type of restaurant.

Which brings me to the second myth.

Myth two: Philadelphia’s restaurant scene isn’t good or developed enough for Michelin to come here.

It’s not a question of whether or not Philadelphia is good enough, but rather a question of whether or not the way our restaurants operate fits into Michelin’s criteria.

Michelin favors consistency and sends inspectors to have the exact same meal at the exact same restaurant in their research. The experiences must match, and they must match the quality of similar experiences whether the diner is in Thailand or in Australia. Where does that leave restaurants like Roxanne, a BYOB that embodies the verve, creativity, and scrappiness of Philly, and where the menu changes every night? And where there is just one chef in the kitchen and one server dashing around the floor? The only consistent thing about Roxanne is that you’re going to be consistently shocked at how smart, delicious, and wacky the food is every time you go. But how about Tabachoy, whose bathroom is around the block from their entrance? Or Lark, which is technically outside the city limits. Boundaries have proven a major sticking point in the battle over Colorado’s stars where Annette, whose chef just won the James Beard Award for Best Chef in the Mountain region, is about 500 feet past the city limit.

Lark would be overlooked by Michelin inspectors for being located in Bala Cynwyd / Photograph courtesy of Neal Santos

And then there’s the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board, a contentious topic in the restaurant industry. It’s one we need to address if we’re going to talk about having Michelin here, because even though inspectors are paying less attention to wine lists and well-developed beverage programs (though, note that all 71 starred restaurants in NYC have these), interacting with a sommelier is often a significant part of going to a Michelin-starred restaurant.

But liquor licenses in Philadelphia are exorbitantly expensive which is a huge barrier to entry for a large percentage of restaurants. For comparison, the market-determined cost for a liquor license in Philly hovers around $250,000. In New York, you’re looking at around $4,500.

It’s not that Michelin wouldn’t pay attention to BYOBs — it’s more about the economics at play. Selling alcohol is how restaurants make money. The profit margin on alcohol is significantly higher than on food. So BYOBs probably couldn’t generate the profits needed to attract talent (from chefs to sommeliers), formally train their front-of-house staff to endear them to Michelin inspectors, and pay for the nice napkins, the nice silverware, and the delicate wine glasses that ensure a seamless, luxurious dining experience.

Having Michelin in Philly would likely concentrate attention on the restaurants that are consistent and have wine lists (or at least the revenue that a wine list would generate), and could exacerbate existing inequities in this city regarding who gets access to funding, what cuisines are prioritized, and who gets to sell alcohol.

Yes, a rising tide lifts all ships. So come on over, Michelin. Our smaller, more independent restaurants and BYOBs may eventually get the trickle-down effect of having you here after you work through our fanciest restaurants.