The Joy of Burning It All Down: Alexandra Holt’s Insurgent Experiment in Fine Dining

Holt’s restaurant, Roxanne, is a middle finger to a sexist, exploitative industry, and to the idea that fine dining must be serious to matter. Is her approach exactly what Philly needs right now?

Dessert at Roxanne (house-made chocolate with hazelnut, mandarinquat and edible money) is chef Alexandra Holt’s comment on the ethics of the chocolate industry. / Photography by Rebecca McAlpin

Retirement Planning

(2 days after dinner service)

On the phone, chef Alexandra Holt and I are talking about the future. For the 24-seat BYO named Roxanne she opened in Bella Vista. For her.

Until recently, Alexandra didn’t see herself having much of a future. She still doesn’t, in some ways. There’s a nihilism in her that’s bone-deep, earned and, oddly enough, freeing. Because when you truly (and I mean truly) have no fucks left to give — when you’ve looked around at the world as it is and decided you want nothing more than to vanish from it — then every day after that can be a gift. Something extra.

“A few days ago, someone asked me if I had plans for retirement,” the 29-year-old tells me, her voice sounding mystified. “And I’m like, retirement? Fucking RETIREMENT? No, man. I just wanna die in a restaurant.”

One Night on Christian Street

(Dinner: 7 p.m., March 21, 2023)

Alexandra steps out in front of the dining room. Every eye in the place is on her. She smiles, says hey, says thank-you, asks about allergies, says thanks again, points out where the bathrooms are, then bolts back to the prep kitchen to pull the Texas toast out of a temporary Emergency Oven that’s only big enough to hold a single half-sheet tray.

Tonight’s menu is nine courses, prix-fixe. Two and a half hours of chili crisp and tater tots, leek culurgiones and escargots. The dinner is expansive, luxurious, goofy, and it represents something like 200 individual plates, every one of which will be prepared by Alexandra.

Alone.

The first course — a foie gras mille-feuille with preserved sea buckthorn and pistachio cream — is already plated, sitting half-done on a sheet tray balanced on a cooler. Lauren Salvo, Roxanne’s only other employee, talks to the crowd while Alexandra graffities homemade hot sauce onto the lozenges of foie-stuffed pastry, then spins to turn her attention to the first load of chawanmushi (second course) steaming on the stovetop behind her. She runs into the prep kitchen and starts pulling bowls out of the steamer rack, stripping off plastic wrap bowed and shrunk by the heat, testing each bowl, then dashing — high-top sneakers pounding the uneven floor and cracked red tiles — back to the hot line.

Alexandra Holt preparing chawanmushi. Holt didn’t want her face photographed for this profile. In an industry obsessed with image, she has gone to a lot of trouble to protect hers, keeping photos of herself out of the public eye. Her work, she says, can speak for her: “I don’t feel like I need to sell all of myself to you.”

“I’ve actually never done this before,” she says. “But it’ll be okay. It’ll be okay.”

Roxanne opened quietly in the fall of 2022. It immediately exploded, won awards (Esquire named it one of the best new restaurants in America), and changed Alexandra’s life. A table here remains one of the hardest-to-get reservations in the city right now. Entire seatings sell out in minutes. On the restaurant’s Instagram, she calls the place “Not a restaurant,” which is half a joke and half not. Because to her, Roxanne is more than just a restaurant. And also less. It is decidedly unserious and yet deeply personal. It’s an expression of joy and dread in equal measure. In conception, it was a furious middle finger to a sexist, classist, exploitative industry in desperate need of change. In practice, it’s a revolutionary experiment in fine dining being attempted four nights a week behind a bright purple door on Christian Street.

Alexandra has been up since 5:30 a.m. She’s been prepping for nearly 12 hours straight. The whole time I’ve been with her in the kitchen, she’s barely spoken except to mutter to herself or repeat cook times under her breath. Her movements have been deliberate, heavy, controlled.

During dinner, though, she’s at the ballet. With service under way, she’s quick, graceful, grinning, existing entirely in the moment, living and breathing for the next plate, the next course. Because, really, there’s no other way for Alexandra to work. She commits. She is willing to throw her whole body into it and make this — this nightly Mad Hatter’s tea party dressed up as a full-on multi-course dinner party for strangers — the entirety of herself for however long is required. Fall apart later. Doubt later. For now, in this moment, there is just this.

And if you ask her, Alexandra will tell you: It is so, so worth it.

On the radio, Juice Newton is singing “Angel of the Morning,” and Lauren steps up to the pass. Alexandra goes to the hot line and pipes the sea buckthorn and pistachio cream onto each plate at the last possible second, sends them up two at a time for Lauren to walk to the tables. She has an extra and hands it to me.

“Hungry?” she asks.

“Sure.” I step to the back kitchen, find a fork, split the mille-feuille and eat. It is remarkable, a weird combination of that fatty, salty, savory hit of foie combined with pistachio sweetness, the crunch of finely executed pastry, and a razor of hot sauce to cut the thickness of all those heavy flavors. It is also an ugly plate. Gloppy. Blobby. Which is something Alexandra does simply because most other chefs won’t. Because gloppy and blobby are traditional plating styles in pastry but typically anathema to savory.

“Good?” she asks, coming back to set up the second course.

“Really fucking good.”

“See? You don’t need to be pretty to be delicious.”

The chawanmushi comes out in small black bowls with preserved mussels, chili crisp and sectioned grapefruit. Alexandra nails it — the egg and miso custard warm and soft and smooth but loose enough to separate into drifting curds when it sits in the mussel broth.

Lauren hovers briefly by the prep table, eating leftovers beside me after delivering the rest of the bowls to the dining room.

“She does this. She’ll just feed me all night.”

Lauren works the floor, sets the tables, serves, washes dishes, and reads the room like a wizard — always knowing who’s having a good time, who needs space, who needs another minute with the potato sundae or cheese cloud or giant gummy bear. Alexandra and Lauren worked together before Alexandra opened Roxanne. During service, they barely have to speak.

Alexandra runs past, pulling half-sheets of boudins blanc.

“I hate you,” Lauren calls after her, grinning. And Alexandra laughs — hard and loud.

It’s the first time I’ve heard her laugh all night. “I know, right? Oh, and I threw in pepperoni because … I don’t know. Because I think it’s funny. Pepperoni and grapefruit? It’s the best.”

And then Alexandra’s gone. I follow her to the hot line, and she’s got a dozen boudins already spitting in cast iron pans on the six-burner, plates lined up behind her, Thermo whips full of homemade La Tur fondue sitting in a water bath, and a dining room full of people. There are seven courses still to go.

Alexandra is singing. “Be My Baby,” by the Ronettes. And she has the biggest smile on her face.

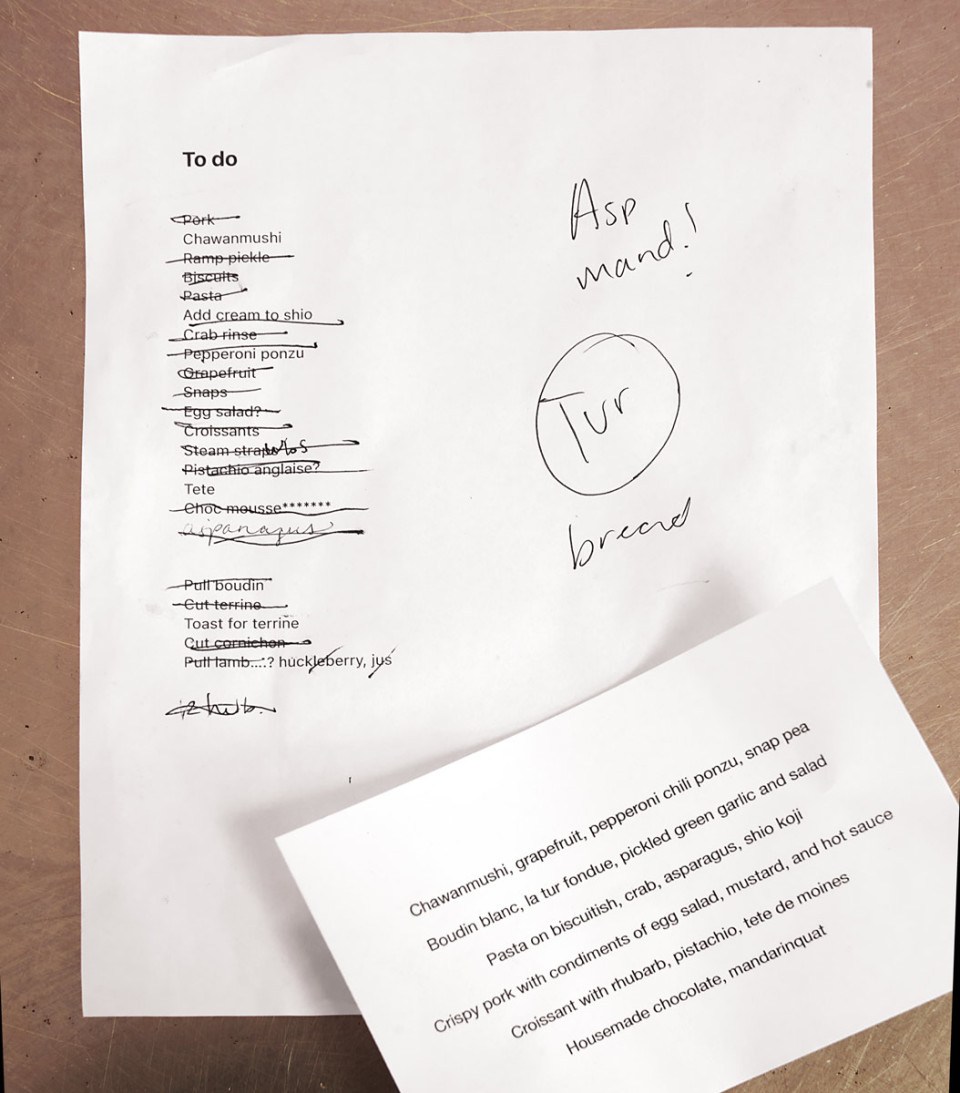

Alexandra Holt’s preplist

The System

(60 minutes before service)

On the butcher-block table in the middle of the prep kitchen, there’s a piece of paper. A single sheet, scrawled on, scribbled over, written in printer ink and ballpoint pen and Sharpie, to do bolded at the top. It’s Alexandra’s prep list, and it contains, among other things, pasta dough, foie mousse, marshmallow and mussels in vin. It fills the page, spreads out from a printed column with items neatly crossed out to a mess of abbreviations, lines, frantic circles. There are reminders to check chix jus and TOTS in all caps. Hoagie salad? with a question mark. Roni! with an exclamation point.

“Service isn’t … hard,” Alexandra tells me, chugging water, standing in the middle of her kitchen at 6 p.m. on a Tuesday night. “Doing it, that’s not hard. It’s everything else.” The first customers will be arriving at Roxanne in a little less than an hour. She drags her fingers through her curly hair, pulls it all back and ties it.

“This?” She points to the to-do list on the table next to her, then lays her hand flat over it, like she’s pinning it in place. “It’s a system. So long as I get all of this done, the rest of it goes by so fast.”

Vanishing

(12 years before service)

To understand how Alexandra got to Christian Street, you need to know where she came from. And to understand where she came from, first you have to know how she died.

It was her junior year of high school. She doesn’t recall exactly how long she was dead, but she remembers that she was in school. She remembers that her heart had been racing all day. Right up until it wasn’t anymore. Malnutrition, apparently stemming from an eating disorder that started when she was four or five years old, made her heart stop.

Alexandra’s disordered eating, and the anxieties and learned behaviors behind it, shaped her life — all of it, the then and the now of it.

She was born in Munich, Germany, raised (sporadically) by a single mother who was always worried about what she ate. Alexandra’s mom was in the military, and if she didn’t maintain her weight, she’d lose her job. That sort of attitude can rub off on a daughter. “It’s something that stuck with me,” Alexandra says. “I had this phase where I was afraid to even touch certain foods.”

Alexandra loves and respects and doesn’t blame her mother, whose name is Roxanne, but she doesn’t talk to her about the issues she had growing up. She named the restaurant after her mother because she likes the irony of it.

Before Alexandra even made it to high school, she had lived in 15 states and six different countries. She followed Roxanne from base to base, posting to posting, or more often just going wherever her mom sent her — to temporary homes where her mother would pay someone to take care of her and her sister for a few weeks or months while she was overseas. Sometimes years.

There were times when Alexandra dreamed of family dinners, of gathering around a table. But the way she grew up, if someone made macaroni and cheese from a box, that was a big night: “Every home I was in was just a place I was at.”

Alexandra recalls an extended stint living with a woman whom she describes as an alcoholic suffering from anorexia. She remembers how fun it was to wait for her to pass out on the floor and see what kinds of objects she could stick in her mouth; how isolating and humiliating it was to know the woman kept food locked away in cabinets, which meant that Alexandra couldn’t bring lunch to school. She learned to avoid the cafeteria because being the kid with nothing to eat was embarrassing. Easier to stay away. To not have to explain herself to anyone. Easier just to be gone.

Alexandra loved soccer — until she got too weak to play. She loved making cakes and decorating them for friends’ birthdays — until she developed a fear that if she touched butter, she’d absorb the lipids through her fingertips. Until she’d switched schools so many times that there were no friends left. For a long while, she ate nothing but Special K Red Berries cereal with skim milk and sugar-free jelly sandwiches on white bread, because they were the only foods that felt safe to her. It took years before she did enough damage to herself that she died from it. She had to lose so many other things before she lost her heartbeat. But eventually, it happened.

“No one cared. There were no parents watching me. No teachers, because I’d been kicked out of so many schools. I was just super-isolated. No friends. No parties. No one.”

She spent her junior year of high school in the hospital. She says it was like jail, like punishment for being sick — the constant monitoring, weight checks, people watching you in the bathroom.

“And you have to understand that dying? It in no way changed how I wanted to live. It didn’t change my eating disorder. I didn’t want to get better. I wanted … let me say, I was really attracted to the idea of vanishing.”

But she didn’t. She died, then she came back. And when you’re talking origin stories, that’s a good one. Jesus. Buffy the Vampire Slayer. They did it. So did Alexandra Holt. And while normally that sort of thing leads to fighting supervillains or saving the world, for Alexandra, it led somewhere entirely different.

In 2011, she decided to go to culinary school.

Terrine with cornichons and mustard

Disaster Management

(45 minutes before service)

I was supposed to hang out in Roxanne’s kitchen to watch Alexandra work weeks ago, but the walk-in cooler died. There was a disagreement with the landlord over repairs, and she ended up canceling service for a week, buying a single-door reach-in fridge from a restaurant-supply company and making do with the limited space it offered.

“It’s better than nothing,” she tells me over the phone two days later. “Plus, it’s a good lesson in not having too much on hand.”

Once the cooler thing gets sorted, I reschedule my visit for a Wednesday in mid-March. At the last minute, Alexandra gets worried. She tells me she’s become so accustomed to spending time alone in the kitchen that the anxiety of having to share her space with another person is just too much.

“There’s no room in my life for other people,” she says. Not now. She lives most of her life alone — which is exactly how she wants it. How she needs things to be right now. She preps alone. Works alone. She has friends, but she prefers to take walks alone, go to restaurants alone (almost always on Thursdays, what she calls her “Inspiration Day,” when there’s no service to prep for), so that she can focus fully on the experience. She isn’t in a relationship, doesn’t want to date when even a handshake feels too intimate for her.

Eventually, we compromise: I’ll come in for a few hours on the following Monday, stay out of the way, be quiet, try not to wreck the vibe. She’s cool with that. Only come Monday, her oven dies in the middle of prep. So now she has to scramble, cancel all the night’s reservations and go dark on a fully booked night. I end up spending Monday night at home, playing Minecraft with my son.

Now, it’s Tuesday, and I’m here. Alexandra barely talks. When I ask her about having to cancel last night’s service, she says only, “That sucked” as she rounds the prep table with a load of preserved mussels in milky broth. The dead oven — her Regular Oven — was a workhorse pro model: big, double-doored, battered, with room for four full-size sheet pans before you even start getting clever. What she replaced it with is her Emergency Oven — a small, shiny black home model that’ll only hold a single half-sheet but has the distinct advantage of actually getting hot.

Every small disaster requires a paring-down of backups, a lengthening of the to-do list. She can’t hold four days of prep anymore, just enough for one night’s service. She can’t cook off entire pans of pork belly or Texas toast, so she does them in shifts — warming to serve five minutes before the plates hit the table. She’s kicked the Regular Oven over on its side, and the Emergency Oven sits on top of it, plugged in among a snaky tangle of extension cords and surge protectors. Every loss forces her more and more into the moment. Every change stresses a system already operating very close to the edge.

When I ask her if she adjusted the menu after losing the Regular Oven, she freezes. Looks off into space, as if calculating large numbers in her head. She says nothing, then snaps back, looks at me, and says, “No.”

She drops the mussels on the table and finds a spoon.

“It’s gonna be fine,” she says. “Probably.”

Diners during the meal

Big in Iceland

(10 years before service)

Alexandra and I are on the phone, talking about culinary school. We’re talking menus and snail farmers and coolers and landlords, baking, Germany, drugs, climate change, and the horrors of living in America at this particular moment in history. All this time she spends alone, and yet on the phone, she sometimes talks like she might never stop.

People go to the CIA — the Culinary Institute of America, where Alexandra ended up after coming back to life — for a lot of different reasons. It’s where serious students of food go to become professional chefs (because where else are you going to learn to make a proper gelée?) and where lots of talented cooks go to polish their résumés and make the jump into the big leagues. It’s where adrift young creative types with trust funds and no sense of direction end up when they decide they can’t make a living drawing anime.

Alexandra studied to be a baker basically because she knew what a cake was. And because she knew that bakers didn’t have to try the food while they cooked. She managed to mostly avoid tasting anything for the entirety of her two-year experience at CIA.

And when I ask her what it was like — going from the life she’d had to suddenly living on campus, being surrounded by food all day, every day, and by people who cared deeply about food in ways that were 180 degrees different from the way she cared about food, she answers immediately, and with a searing honesty.

“I totally fucked it up. I fell in love. Can you believe that? I fell in fucking love, and it fucked everything up. I moved off campus into a house with five guys who were all growing weed. And that was such a mistake. My school experience was all about drugs and partying. I was eating Adderall all day just to get by. Like 17 Adderall a day most days. I was never sober.”

She got good grades, anyway. She always got good grades. And after graduating from CIA at 20 in 2013, Alexandra interned in Pittsburgh, then did a stage at Fork under Eli Kulp, back when Sam Kincaid (who would later open Cadence in Kensington) was running the pastry department. She went to Baltimore (because she had a place to stay there) and worked at the Ivy and Cinghiale, then bailed for Washington, D.C., and a position at Fiola — her first job at a Michelin-starred restaurant.

On the phone, she sighs, remembering. “That’s the training that I wanted. To be able to walk into any kitchen in the world and hold my own.”

She explains how at first, she just did pastry — baguettes and croissants, desserts and table bread. But pastry alone was never going to be enough for her.

For a certain breed of cooks, it’s the static they’re after. The white noise of panic on an understaffed Friday night, dinner rush, pre-theater. They want the brainlessness of repetition (prep) followed by the roar of loud voices and a chattering ticket printer and the hot flare of flames. They want 14, 18 hours of somewhere to be every day, followed only by collapse. They want desperately to give themselves to something and be consumed by it, to find that place of quiet focus that only comes from operating as close to the edge as you dare step.

Alexandra was very much one of those cooks. She was looking for more than pastry alone was ever going to offer. And she found it. She started doubling up — doing her pastry work and then covering garde-manger, too. Plating salads and cold apps. She’d work a day shift in the bakery, then stick around to work the line because the line was where the action was. Where the fire was.

After D.C., she went to Chicago for a six-month stage at Alinea — arguably one of the best restaurants on Earth just then, and still one of the most exclusive training houses in the U.S.. The kind of place where young cooks will step on each other’s necks just to work for half a year, unpaid.

Alexandra wanted it because it was the hardest, most unattainable thing. She went and let her life fall apart. She was living in another cook’s basement, barely eating, barely sleeping.

“Back then, I was still really willing to die for my career, because I was young and full of coke, so I was like, ‘Fuck yeah!’”

In Chicago, after her stage at Alinea, she got a job at a restaurant called Two. She was brought on as executive pastry chef but also worked the line. They were long days, longer nights, and she was drinking too much, by her estimation. And then, late one night, walking home from work, she was attacked on the street and beaten up badly — cheekbones broken. She spent weeks in the hospital. Couldn’t work.

Over the phone, her voice sharpens. “I couldn’t have anyone see me like that,” she says. “So I left.”

Rather than having anyone see her broken or having to explain why, she got on a plane and went to Germany. For two and a half years, she worked in Stuttgart, Iceland, Italy, racked up more Michelin stars on her résumé. She tells me how they wrote articles about her there in magazines and newspapers, covered her like she was a visiting celebrity. “I finally got this little taste of being someone.”

And she was happy with that. She might have stayed. European kitchens had their own problems (a rigid hierarchy, male-dominated, “a whole other level of sexism and a whole other level of awkwardness”), but then the pandemic happened. The world changed. Alexandra decided she had to come home.

Duct Tape and Prayers

(30 minutes before service)

The hot line at Roxanne is small — a boxy space with just room enough for a cold table, a warming oven, a six-top burner, and a long, narrow charcoal grill that looks like a window planting box covered with chicken wire.

The prep kitchen is bigger but cluttered and doubles as the dish room, storage room and pantry. There’s a baker’s rack pushed up against the dead walk-in, wire racks stacked with disordered pots, boxes of curly kale and lemons bright as fireworks.

Everything is cramped, crumbling, breaking down, held together with duct tape and fervent prayer. But you put Alexandra and Lauren into it — watch them move through it and use every inch of it and see the habitual turn of the hips and shoulders as they brush past each other in the narrow throat of a hallway between the kitchen and the line — and it makes sense. This is a galley made for their particular battleship. Inside these walls, Alexandra is strong. She feels like she can do anything. The proof of that is in the months of services stretching out behind her, the fully booked weeks stretching ahead.

What Alexandra does at Roxanne can only be done night after night and week after week so long as she’s really fucking focused and really fucking good. And, of course, so long as nothing goes wrong.

“Thirty minutes,” Lauren calls from the pass.

At the prep table, Alexandra hunches her shoulders, mutters to herself. The iPhone in her apron pocket is set with 20 timers. She bites the cap off a Sharpie and scrawls cook times on her forearm among the tattoos, then starts prepping the snails.

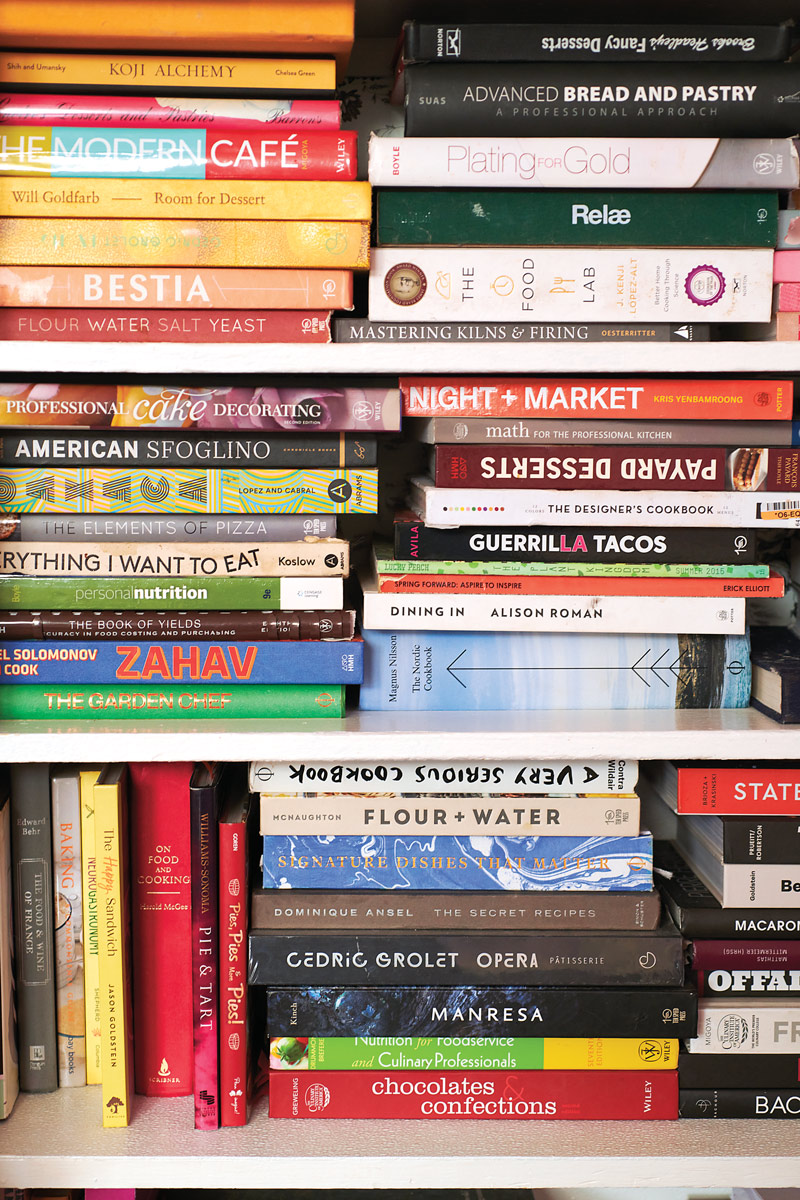

Cookbooks in the dining room

Devil in the Kitchen

(Two weeks before service)

“I always thought pastry was fucking boring.”

We’re back on the phone again, Alexandra and I.

“Seriously, it seems like such a shitty way to live to me — to find this thing that you can do the same every day just so you can get through it.”

What she’s talking about is the dyad of back-of-house life, the essential disconnect between pastry and the hot line. In the contained, insular, submarine world of high-end professional cooking, pâtissiers and cooks are like the Jedi and the Sith, the light side and the dark, one controlled, intellectual, ruled by science, the other emotional, instinctive and living in fire. It’s rare for one person to be able to do both even passably well. Someone who can execute on both sides of that divide, night after night, on a professional level is a unicorn. Rarer than rare.

Alexandra staked her career on being a unicorn — on going from cold to hot, quiet to loud. If, in Roxanne’s kitchen, it’s Alexandra’s to-do list and remarkable focus that make the impossible possible, in fine-dining kitchens, it’s the brigade system. That’s what turns a thousand pounds of raw materials into fancy dinners every 14 hours and allows for the orderly, consistent production of hundreds of identical plates of food, night after night. A big, professional kitchen is, essentially, an assembly line with human beings as the machines. Power starts at the top, from the exec chef who has it all to the station cook who has none. Cooks will work long hours. They’ll work sick, work hurt, work without complaint, because the cooks know they’re just machines — immediately replaceable should they begin to malfunction in any way. This system is militaristic, hierarchical, aggressively anti-collaborative. It’s almost designed for abuse and exploitation, for harassment. And for as long as there have been kitchens, this has been the standard by which they’ve been organized. Also, they’ve almost always been staffed by men.

Alexandra laughs. “Yeah. It’s the same shit in every kitchen. You’re always in these rooms full of men. And being in a room full of men is … challenging.”

She doesn’t want to talk specifically about harassment in the industry except to say that it exists, and that it’s endemic. “If you know, you know,” she tells me. “But I’m a piece of shit for talking about it, not they’re a piece of shit for doing what they did. In any conversation like this, I already know that I lose because I’m the woman. So I will always fucking lose.”

Roxanne is, in part, Alexandra’s answer to some of fine dining’s problems. When she does the entire menu herself, there’s no split between the Jedi and the Sith. With no brigade, there’s no hierarchy, no power differential, no abuse. No one to answer to but herself. It’s all contained. All perfect.

Until it’s not.

And Tonight’s Emergency Is …

(10 minutes before service)

“Towels.”

Standing in an alcove in the hallway between the two kitchens, I look up, and Alexandra is standing there, waiting for a bucket to fill with water from the hand sink, looking at me. In the dining room, Lauren is showing customers to their tables. Everything is candlelight and hot purple neon.

“Towels,” she repeats. “That’s tonight’s emergency. We don’t have any towels.”

In a working kitchen, towels are currency. You can run through 50 a night, easy. I’ve worked in kitchens where the executive chef had to lock the towels in his office during service just to keep the line from burning through a week’s linen order in six hours. What makes the problem even more galling here is that Roxanne has plenty of towels, but the towels are all in the basement, and Alexandra can’t get into the basement once the tables in the dining room are set up because she can’t open the door. So right now, she has three, maybe four kitchen towels. For the whole night. She turns off the water, lifts the bucket, walks away.

“Here we go.”

The pass during service

A Portrait of the Artist as a Fucking Wreck

(Three years before service)

I don’t know why Alexandra picked Philly. I’m not sure she does, either. I know she feels strong here. I know she feels like this place — more than New York, more than Chicago, more than Munich or Stuttgart or Baltimore — is somewhere she can do something. Make a difference, maybe. A name for herself. A life.

She was back in Germany when she rented an apartment in Philly over the phone, sight unseen. She got a job by messaging Chris Kearse at Forsythia and telling him she had a plane ticket and needed somewhere to work. After Alexandra’s stage at Forsythia, Kearse hired her on the spot. Alexandra was a walking pastry department that could also work the line, run a kitchen, bang out a hundred covers a night plus desserts. And just then — in early 2021, the middle of the pandemic — that was incredibly valuable. No one knew what was going to happen to the restaurant industry, and there weren’t enough bodies to make the machinery go.

“You just kill yourself for someone else,” she says, trying to describe what those days were like. “Because that’s what’s expected.” Because that’s the job. In Austria, she’d fractured her spine and needed surgery but avoided a procedure because she didn’t want to take the time off. She was still in pain at Forsythia, but it was a new job, a new kitchen, and she didn’t want to let anyone down.

Alexandra lasted five months before it all became too much and she quit. Her gig at Forsythia was supposed to be her way to get to know the industry in Philly, make connections. But she felt like she had no choice. “I was really depressed, because I thought this was going to be my thing. My in,” she says. “So I started drinking.” All day. All night. Then she’d spend the whole day hungover. It was a circle. A spiral she couldn’t escape from. This went on for a long time. She can’t tell me how long. She doesn’t remember most of it.

“And then, one day, I kinda just … ” Alexandra pauses, considers her words. “Stopped wanting to die, I guess? I stopped caring about wanting everyone to be my best friend.”

Alexandra sobered up. Went outside. Started walking.

“Some days, I’m not even sure how I got this far.”

Sometime around January 2022, she passed the space at 912 Christian Street that used to be Sabrina’s. It was empty. Victim of the pandemic. Of that moment when it seemed like every restaurant was closing and no one was opening new ones.

“But I thought, what if I open my own restaurant?”

A time for miracles.

“So I did.”

A $500 deposit got her in the door. Rent was $2,500 a month. Alexandra had spent years living cheap, sleeping on couches. She’d saved, invested, had an eye, she claims, for picking stocks. Since the space had been a restaurant before, it had the right bones. She ended up doing all the renovations herself. All told, she got it done for $60,000, and every dime of it was her money, because no one else was going to offer her any of theirs.

“No one here knew me,” she says. Or, if anybody did, it was only through Pastry Slut — her catering/pop-up business that, she freely admits, was an Instagram hustle to get her name out there, done almost entirely out of her apartment kitchen.

“I was the only one who thought I could do this,” she tells me. “But these people have never seen me at my other jobs. They’ve never seen me at, like, Forsythia, doing a hundred covers a night on the line. And it was nice, right? Knowing these people thought I couldn’t do it and I knew I could? It was like, You’ll fucking see. … ”

Alexandra never intended for Roxanne to be a one-woman show, but no one she interviewed understood what she was trying to do. Or thought she was qualified to run a kitchen. Most of them, she says, thought they were helping her by coming to work.

“I just hated them all,” she says, and on the phone, some of the old fury lights in her voice. “No one’s doing me a favor by helping me out. This is a paying job. You have to want to be here.”

In the end, Alexandra couldn’t imagine sharing a space with anyone she interviewed, so she ended up hiring no one. And then, time simply ran out. The space was ready, the menu was written, the money was gone, and she just had to open. Alone.

On opening night, Alexandra charged $55 for 10 courses. Service lasted four hours. Two seatings. People liked it, but Alexandra says she was a disaster. She was still prepping when the first customers were walking in — cutting down beef tartare. She’d have to pause between courses to wash dishes and silverware, because she’d underestimated just how many plates and forks and bowls she was really going to need to serve the entire dining room twice.

“A lot of cooks expect a lot from themselves. And I was a little naive thinking I could do it perfect all by myself the first time.”

Someone less driven might have stopped. Someone less committed would have hired more help, perhaps. Someone more risk-averse might have said, Whoa, this was a bad idea and immediately become an accountant or a bus driver or the circus performer who sticks her head in the lion’s mouth. Anything.

But Alexandra went back and did it again. Then again. She started getting migraines, nosebleeds, throwing up. The stress, the hours, the anxiety, it was killing her, but she couldn’t stop.

She tells me she learned a lot from the early days of Roxanne. She scaled back service and hours and found Lauren Salvo to help. She simplified plating and paused (temporarily) her idea of also doing retail pastry on the weekends. But the most important thing she learned was that she could survive it. Which meant that actually doing it was possible.

Candy eyeballs for tiramisu

All the Small Things

(2 hours into service)

The boudin blanc goes out under a cloud of fondue topped with a doodle of pickled green garlic reduction. Alexandra changes up the plating at the last minute, swapping classic white pasta bowls for high-walled peach and yellow ones.

Next is “pasta on toast” — leek culurgiones on thick slices of Texas toast, topped with shio koji, mandarinquat, and Peconic escargots from her new snail guy. At the stove, Alexandra is dancing while the leek dumplings swim.

After that, Lauren resets the dining room for the next course, and Alexandra takes a breath before plating kale-and-beet salads, then a complicated setup of roasted pork belly with salmon tartare, mustard, homemade hot sauce, and roe with crème fraîche.

“Playlist!” she shouts, then pulls out her phone and switches up T-Pain for Blink-182. “People go crazy,” she says when “All the Small Things” comes on: “They bang their heads into the walls.”

From where I’m standing in the prep kitchen, you can hear the crowd laughing. There’s a joy in the air that Alexandra sucks in like oxygen as she sends out dessert: steamed whole apples with bay leaf and vanilla; fresh mandarin ice-cream sundaes with homemade marshmallow from her pink KitchenAid and homemade tater tots soaked in simple syrup and sprinkled with sanding sugar; a deconstructed tiramisu with a powerful marsala pastry cream, served flat and white, in a shallow bowl, decorated with little candy eyes.

Alexandra laughs as she adds them to each plate with tweezers. “They love it. I don’t quite get why, but it is cute.”

There’s an anarchic glee to what Alexandra does at Roxanne. A channeling of madness for flavor, for texture, for strange juxtapositions that don’t work rationally or intellectually but — filtered through her obsessive mind and constantly churning recollections of girlhood, fear, exultation, a thousand cookbooks and a dozen different restaurants — touch some different level of wonder. Almost every plate feels imaginary, like something you’d only eat in a dream. Like a dinner a child might invent, not yet having developed any concrete notions of what is or isn’t food.

Filming a dessert course

Watching it All Burn

(2 days after service)

The whole point of Roxanne, according to Alexandra, is to make people laugh. It’s to remind them that dinner is supposed to be fun.

“I’m sorry we’re not sticking a silver spoon up anyone’s ass when they walk in,” she says. “But we’re there just to give people a good time. A memory of a few good hours in their day. So I put eyes on their tiramisu, you know? I just want people to have that moment in their day. I want them to experience something new. I’m not a doctor. I just know how to cook. So this is what I do. To help.”

And maybe that’s enough. Maybe Alexandra’s restaurant doesn’t need to be anything more than that. But it is.

Roxanne is, at every level, an experiment — a rough, physical refutation of so much that the industry finds sacred and necessary. From simple, harmless resistance (like putting potatoes on a dessert plate) to asking structural questions about whether or not a kitchen requires a brigade to function, Roxanne operates like a test of what, exactly, a restaurant needs to be weighed against what one can be.

The restaurant industry is a relic — a lumbering, lurching, fad-and-fame-obsessed monstrosity that aspires, occasionally, to art by following only its worst impulses. It eats its own young with frightening speed, asks too much, gives too little, and is fanatically resistant to change in the way that all old monsters seem to be. Revolt will likely not happen from within. Only from without. And it won’t happen at all without someone (or lots of someones) willing to take a chance on something different. Even if it’s only because they have nothing left to lose.

No one except Alexandra Holt could have opened Roxanne. Her life, her mistakes, her self-sabotage, her triumphs — they’re there on every plate. She understands better than most that sometimes you have to do the impossible just to prove that it’s not. You have to be willing to let it all burn, and then, the next night, do it all again — because that’s the only way to make something you love better for those that come after you.

“Sometimes I like watching it burn, and sometimes I just want to, like, give everyone a flower,” she tells me. “But this is the most stable I’ve ever felt, having this impossible task to complete every day. I just want to show that it can be done. I want to be present in this moment when I am so fucking happy.”

And then she tells me she has to go. Tomorrow, she has deep cleaning. The day after that, recipe testing. Today, though, is Inspiration Day. She has a new menu to dream up. A new to-do list to start.

But first, she’s going to take a walk.

Alone.

Published as “Fine Dining on Fire” in the May 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.