Panettone Is the Mount Everest of Holiday Baking

Why the laborious process of baking panettone has become an obsession for some in our city.

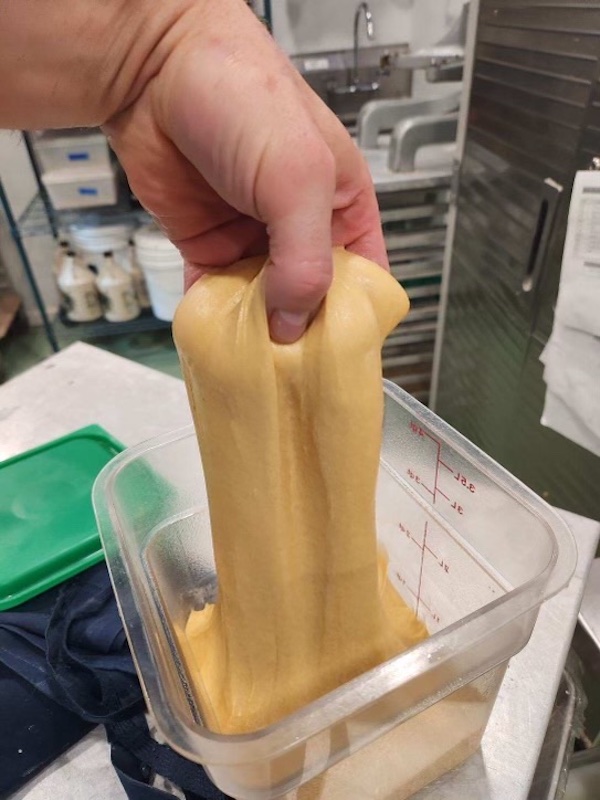

It’s panettone time, baby. / Photography provided by Alex Bois, owner and head baker at Lost Bread Co.

“My brain is fully broken,” says Dayna Evans. “All I think about is panettone.” Evans, the former editor of Eater Philadelphia, recently left the world of journalism to focus full-time on her home baking project Downtime Bakery. She says panettone is her Mount Everest.

Panettone is known to many as the boxed Italian sweet bread that’s gifted and eaten around Christmas. When it’s made industrially in the U.S., panettone tends to be largely unappealing — dry and without much flavor beyond the occasional chunk of shriveled fruit. The version of panettone available in Italy is almost unrecognizable in comparison to what you’ll find in American grocery stores. It’s light and wispy, studded with chocolate, candied fruit, nuts and aromatics. But some bakeries in the States have taken up the challenge of making panettone themselves, trying to recreate the magic that Italian bakeries have been producing for years.

“A lot of people think of panettone as just a boxed cake that sits on the shelf forever,” says Emilio Mignucci, vice president of culinary pioneering at Di Bruno Bros. “When we cut it, let them taste it, people are like ‘holy cow.’”

Di Bruno Bros.’ panettone selection ranges from a $30 version to mid-tier options to an $150 limited collaboration with the San Francisco-based company, From Roy, which specializes in panettone and makes some of the best versions of it in the world. According to Mignucci, panettone sales have grown over the last five or so years as more Philly customers learn how delicious it can truly be. Mignucci says he’ll eat at least 10 panettoni in 2022. And that he’ll be sad in January when it’s all over.

This year, my own personal Instagram feed has been full of Philadelphia bakers and bakeries showing off their versions of the Italian Christmas treat. The pattern makes sense on paper: Philadelphians love Italian goods, and the city’s bakeries are more than willing to cater to that, especially around the holidays. But, even for the most seasoned bakers and pastry chefs, the process is notoriously challenging.

The success of any panettone is largely based on its starter. To begin the process of making this sweet laborious treat, a baker must feed their sourdough starter every three hours for 12 hours. The dough can be made only once the starter has been fed four times. “People spend a long time getting their starters ready for panettone season,” Evans explains. “Getting your starter to be healthy and strong enough, and to have the right amount of cultures and bacteria in it to make the dough rise is like a training process.”

Michal Shelkowitz, the pastry chef at Vetri Cucina — where the team makes panettone almost every year; though notably not this year because Shelkowitz tells me the restaurant is simply too busy — says Marc Vetri himself is dedicated to perfecting their panettone, mostly by changing up the starter. “Like 70 percent of the success of your panettone is in your starter,” Shelkowitz says. “So fine-tuning means cultivating your starter. Sometimes a week of feedings of the starter before you can change one thing.” In the past year, Vetri has begun chemically testing the pH of his starter in order to perfect his panettoni, which I can confirm are delicious. The magic of great panettoni lies in this touch of acidity from the natural fermentation, balancing the bread’s sweetness with a slight sour flavor and creating an addictive, can’t-stop-grabbing-another-slice kind of experience.

In addition to working with the subtle nuances of a starter, the other major menace of baking panettone is ensuring that the dough can hold a staggering amount of butter and egg yolks while retaining that highly prized, cotton-candy-like texture. Bakers mix their dough for a 45- to 60-minute period such that it develops ample gluten, the protein structure that allows flour-based products like bread to stand up.

Alex Bois, owner and head baker at Lost Bread Co., began making panettone years ago. But it was only recently that Bois found a baking method that yielded the proper panettone structure while reducing waste. “If you make a few hundred panettoni, you end up with gallons and gallons and gallons of egg whites,” Bois says. “For me, the two things that I’ve been interested in over the past few years have been how do we do this without as much waste, and how do we do this in a way that’s a little bit more sustainable?” After some trial and error, Bois developed a process that replaces most of the water in the recipe with egg whites, amping up the dough’s protein structure. The flour is a red spring wheat, which they mill themselves.

For Shelkowitz at Vetri Cucina, the only baker I spoke to who is baking panettone alongside a busy restaurant production schedule, the greatest challenge is the time commitment. “You really need an hour-by-hour schedule to make panettone in a restaurant,” Shelkowitz says. “You don’t know if it’s going to work out until the end of the second day. You can’t troubleshoot along the way. Everything can be great day one and then when you go to add the butter the whole thing can fall apart, and you’re not really sure why, and you can’t fix it. You just have to start over.”

Evans, for her part, is in her fourth year of trying to perfect her panettone. “Every year for the first few years, I would try it once and then be like, ‘no this isn’t working,’” she says. This year, she made six batches of panettone and none of them behaved themselves: “I have this idea in my head of what I want it to be — that thing where it just mushrooms above the paper, and it just hasn’t gotten there.” She’ll revisit the project next year, with plans to start sooner and do more research.

Even with its headaches, these Philly bakers agree: There’s something about panettone that takes them down a rabbit hole. “I do think you do have to lose your mind a little bit,” Bois says. “I definitely feel like I’ve clawed my way back to panettone sanity, but after many years of obsession.”

Shelkowitz says that she thinks, for the truly devoted, the pursuit of some theoretical faultlessness is part of the pleasure: “I don’t think it’s that hard to pull off a good panettone. But I think a great panettone — a perfect panettone — is really hard. Marc [Vetri] has been working on it since September this year, but perfection is really very subjective.”

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to eat an exceptional panettone — fluffy and egg-yolk-yellow in the center, streaked with chocolate and jeweled with candied pear. It wasn’t the first version I’d tried this year, but I’d never had the chance to cut one down the middle, sawing through the crispy dome on top and into the cobweb-like interior. To me, it was perfect — made even better because I knew the baked good was held together by some subtle law of chemistry and semi-mythical processes, and because I knew that just a few weeks later, it would all be gone. I’d have to wait another year to slice through another panettone.