The Year That Restaurants Said No

In 2020, some members of the Philly dining world, from owners to servers to cooks, took a look around and decided that the status quo — low pay, long hours, unpredictability — was no longer working. The changes they’ve made in response could reinvent the way we eat out in Philadelphia.

Martha is one of the places reinventing Philadelphia’s restaurant industry. From left: server Britt Luna, sous-chef Bobby Slocum, executive chef Andrew Magee, Olivia Caceres, co-manager Daniel Miller, and bartender Nik Shumer-Decker at Martha / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

On a hot day in the summer of 2020, Jennifer Zavala — a true Philadelphia multi-hyphenate known for her stint on Top Chef, her time illegally selling tamales out of a van, and her status as one of the city’s few cannabis chefs — was hosting a popular birria pop-up at Underground Arts. Hundreds of people had pre-ordered and lined up, gobbling down her birria tacos and ramen and sipping to-go cocktails. The event sold out, and she should have been delighted. Instead, Zavala found herself perplexed. The staff’s total tips that day amounted to just under $40. Amid the outpouring of professed support for restaurants on social media, it didn’t add up. So for her next pop-up, a few weeks later, Zavala decided to add an automatic 20 percent gratuity to all orders. No one seemed to notice.

Up until that moment, Zavala had no plans to ever open up a place of her own. She’d made her name with events off the beaten path, and after years of condescension and abuse, bad hours and worse pay, she’d given up the idea that there was a place for her in a formal restaurant.

Jennifer Zavala, chef and owner of Juana Tamale / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

“I was like, you know what? I’m going to show all of you,” Zavala remembers. “All those people who say there’s nothing to be done about the wages and working conditions in this industry? They’re lying.” She was sick, she said, of listening to professionals with more money and prominence say it was impossible to change the food game, to raise prices or add a gratuity. She wanted to make a point.

Some six months later, Zavala opened Juana Tamale to consistent crowds just as large as her Underground Arts audience. People flock to Juana Tamale because the Mexican food is fucking good: juicy, crisp-edged pockets stuffed with rich beef stew, and cups of ramen noodles topped with caps of melted cheese and the same birria. But the automatic 20 percent gratuity charge hasn’t gone over as easily at the restaurant as it did during the pop-ups in 2020.

Juana Tamale’s Google and Yelp reviews are now littered with what can only be described as rants against the gratuity policy, despite clear signage in the restaurant communicating its inclusion. Both in person and online, some diners call Zavala disrespectful and refer to the policy as a scam. Zavala doesn’t budge.

A sign reminds customers of Juana Tamale’s automatic 20 percent gratuity charge / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

These nasty comments reveal something simple but radical about her approach to running her restaurant: Zavala says no. She says no to customers who don’t want to pay the gratuity. She says no to customers who request modifications to the menu. She says no to opening her restaurant more than three days a week, because she believes everyone needs time off and she doesn’t want to stretch her team and supplies too thin. She says no all the time.

Zavala is one of a small group of restaurant owners and employees who looked around in 2020 and decided that the status quo wasn’t working in Philadelphia anymore. The solutions they’ve come up with are playing out in subtle (and not so subtle) ways across the city.

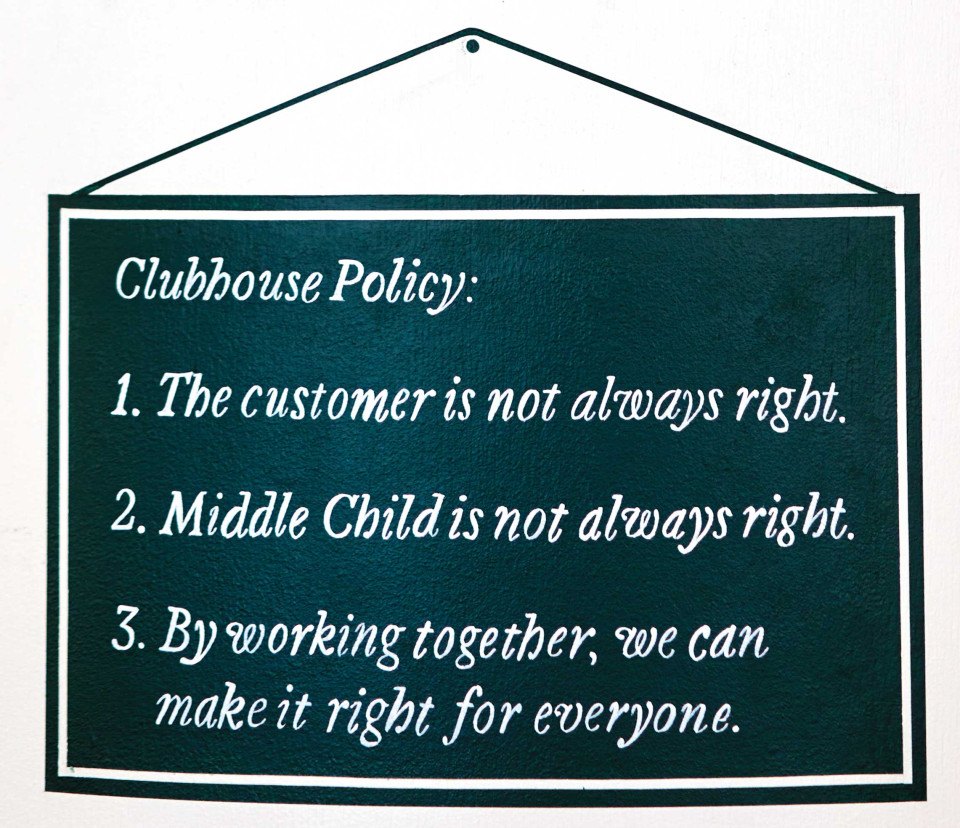

When much-lauded Middle Child Clubhouse opened in 2021, owner Matt Cahn had a sign painted on the wall in the dining room that lays out the restaurant’s basic operating policy. “The customer is not always right,” it reads. “Middle Child is not always right. By working together, we can make it right for everyone.” Cahn, the owner of both the Middle Child sandwich shop in Washington Square West and Middle Child Clubhouse, its more raucous restaurant counterpart in Fishtown, says the sign is there to get ahead of the idea that the team must always say yes.

From left, sous chef Alex Valletta and cooks Carly Whiton and Andrew Senken prep before service at Middle Child Clubhouse / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

“If someone comes in and says, ‘I don’t really like avocado, can you substitute something else?’ — that seems like a small request,” he acknowledges. “But then there are 50 other people in the dining room making those requests, and that makes things really difficult for the team in the kitchen, and it can be expensive for us.”

Both Middle Child locations allow customizations where Cahn and the team feel they’re possible, like offering gluten-free bread and allowing ingredient omissions on sandwiches. Meanwhile, other Philly restaurants have taken a more strident stance on order adjustments.

Middle Child Clubhouse’s policy hangs for all to see / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Anyone who has eaten at Nok Suntaranon’s city-transforming Thai restaurant Kalaya has seen this in action. Suntaranon and her team roundly refuse to compromise on heat levels and ingredients like cilantro and onion, which are often flexible at other Thai restaurants. Much like Zavala, Suntaranon dealt with nasty reviews when she first opened, largely from people who wanted her to compromise her food to suit their preferences. But she held strong, and her point was made. In 2020, Esquire called Kalaya one of the best new restaurants in the country. In 2021, Suntaranon announced a huge second restaurant, to open in Fishtown sometime in 2022. This summer, she was nominated for a James Beard Award for Best Chef: Mid-Atlantic. In case it wasn’t clear: Suntaranon doesn’t need your input about how her food should be served.

From left: Middle Child’s dining room sign; a “West Coast”-style pastrami sandwich at Middle Child Clubhouse / Photographs by Gene Smirnov

At Her Place Supper Club, Amanda Shulman’s tiny dinner-party-style restaurant, the communal way of dining makes allergy- or dietary-related substitutions nearly impossible. Shulman serves 24 people the same eight dishes over four courses. It all relies on her ability to offer every guest the same thing. Dinner here is designed to feel like you’re eating at Shulman’s home — and no one would bust into someone’s house and demand a special meal, right? “I absolutely hate saying no to people,” Shulman says. “But if I’m distracted trying to cook a piece of fish for someone who doesn’t eat duck, both the duck and the fish are going to suffer.”

The limitations that the club has put into place — closing often for vacations and R&R breaks, restricting menu accommodations, only offering two seatings a night — are partly to ensure that Shulman and her small team can continue to execute at an exceptionally high level. She says these boundaries represent the current state of the Philadelphia restaurant scene. Right now, it’s harder to find staff, so the restaurant needs to work for the team she has in place, and that means the guest has to say yes to a non-traditional experience.

Even as some business owners try to improve conditions for their teams, other groups of workers have decided to take matters into their own hands. Union organizing efforts are happening at a handful of coffee shops and bakeries across the city, including Good Karma Coffee, Old City Coffee, several Starbucks locations, and Korshak Bagels.

“I think the popular imagination is such that people think union jobs are only at these big factories or other huge companies, like Starbucks,” says Alex Riccio, a staff organizer at Workers United who’s supporting these and other unionization efforts in Philadelphia and nationally. “At every workplace, the power dynamic exists, and it’s tilted toward the boss. With smaller mom-and-pop shops, it’s often worse, because there’s often a very ideological component to it. People work day-to-day with these business owners who are trying to figure out ways to squeeze every last penny out of them, because that’s how capitalism works. But at the same time, the owners act like benevolent benefactors — like parental figures.”

From left: Korshak bakers Brett Barnes and Mary Thomas; everything bagel prep. / Photographs by Gene Smirnov

The 12-person team at Korshak Bagels unionized last summer. In a rare turn for such organizing, owner Phil Korshak agreed to voluntarily recognize the union. But even in a workplace where the owner is willing to do that, the ability to bargain with management significantly improves the lives of the employees. Collin Zastempowski, the steward for the Korshak union, says that in a comparatively good workplace like his, a union still guarantees a level of consistency that helps workers feel valued, which in turn allows people to stay in the restaurant industry. It also creates more competition among bosses to make workplaces more sustainable.

“Without a union, a boss can change the terms and conditions of employment at will,” Zastempowski says. “With a union, they have to negotiate if they want to change anything about how pay is structured or anything like that. With a union, you have people who will stick up for you — ensure that you have a fair and just workplace and a dignified workplace.”

The concept of working with dignity came up over and over as I reported this story. For a long time, restaurant and other hospitality workers have accepted long hours, low pay, and little ability to take time off or plan their lives as part of the bargain of the biz — a biz that’s sometimes romanticized despite these realities. The pandemic has driven some Philadelphia restaurant workers and business owners to question these standards and look for different approaches to their professional lives.

Alex Yoon observes repairs after a water main break on his restaurant’s street / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Earlier this year, Little Fish BYOB in Queen Village reopened with a surprising schedule change aimed at dealing with some of these questions. Alex Yoon, the chef and owner, took a pre-pandemic trip to Paris, where he ate at a couple of restaurants that open only on weekdays and shut down on weekends to give the staff a shot at a normal life. He was inspired by the idea and decided to give it a shot himself.

“I knew that I wanted to be able to have days off, and I wanted to give that to my team as well,” Yoon says. “We’re hoping that if we’re able to do a schedule like this, we’ll attract more people from younger generations — people who want to be in the restaurant business and who will hopefully stay in it because they see that you can actually have a good life.”

Chef Alex Yoon of Little Fish / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

This desire to professionalize in order to keep people in the business was also a motivating factor at Martha, the cozy wine bar and restaurant in Fishtown that reopened in 2020 with a mandatory 20 percent gratuity included on every check. Martha’s gratuity charge is divided among every member of the team and contributes to other benefits, along with providing a guaranteed income for servers. The restaurant pays 50 percent of full-time staffers’ health insurance, with an additional 10 percent added for every year they’ve worked there. And Martha offers a COVID relief plan that pays a day rate if someone on staff is exposed to the virus or gets sick.

Beyond the benefits, Martha’s working schedule is set and predictable. Co-managers Olivia Caceres and Daniel Miller say this has allowed them to hire better staff, function with less turnover, and build their own sustainable version of the restaurant business. “Daniel and I, we love hospitality,” Caceres says. “We’ve chosen it as our career, but it’s still such an unstable industry. There’s a dignity in being able to plan your life, and everyone deserves that. We just hope that the future looks a little bit more like this, so people can look at this industry as something they can find a future in, as opposed to just trying to make some cash and leave as fast as you can.”

On the day we speak, Martha is closed, but Caceres and Miller tell me a handful of staff members are at the restaurant anyway. One teammate who loves plants is being paid to take care of the garden. A couple of the bartenders are working a prep shift, developing new cocktail recipes. Making space for people’s passions, Caceres and Miller say, has made the whole place better: better ingredients, better cocktails, happier staff and less turnover.

Martha co-manager Olivia Caceres / Photograph by Gene Smirnov

At Martha and the other restaurants pushing new industry standards, people get to bring a little more of themselves to work. The happier that people are working in this difficult industry, the more restaurant experiences can evolve into nights diners would never know to ask for. It’s this humanity, perhaps, that’s beginning to redefine Philadelphia’s restaurant industry.

There was a long stretch of the pandemic when it seemed like everyone got fed up with cooking and eating. Even I, a real live food writer, couldn’t figure out what I wanted to eat. These moments gave me intense clarity about what restaurants bring to my life. When Poi Dog, Kiki Aranita’s ode to Hawaiian cooking, announced it was closing in 2020, I placed one last order for Spam musubi and a poke bowl. It was then that I was reminded of what we were losing. Aranita’s musubi was salty and sweet and perfect, so different from anything I grew up eating in my North Carolina childhood home. “This is what I’ve been missing,” I remember thinking as I sat, once again, on my own stupid couch, looking at my same stupid walls. Aranita’s food was served on her terms, and that’s why it tasted so good.

It should go without saying, but the past two years seem to show that we must say it loudly and often: Restaurant workers deserve dignity in their work. That’s reason enough for us diners to deal with “no” as an answer every once in a while. And when businesses get to set their own rules about how they operate, the food gets better, too. Kalaya’s fiery chicken curry is proof; so are the smiles on diners’ faces when they leave Her Place Supper Club; so is Martha’s ever-evolving cocktail list. We’re lucky to be eating in Philadelphia right now — to be watching the dining culture change incrementally. There might just be a better restaurant industry out there, and we can see glimpses of it through tamales and hoagies and bagels. No, you can’t always have it your way. But maybe your way was never better.

Published as “The Year That Restaurants Said No” in the July 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.