This Could Be the End of Restaurants as We Know Them. Maybe That’s Not Such a Bad Thing.

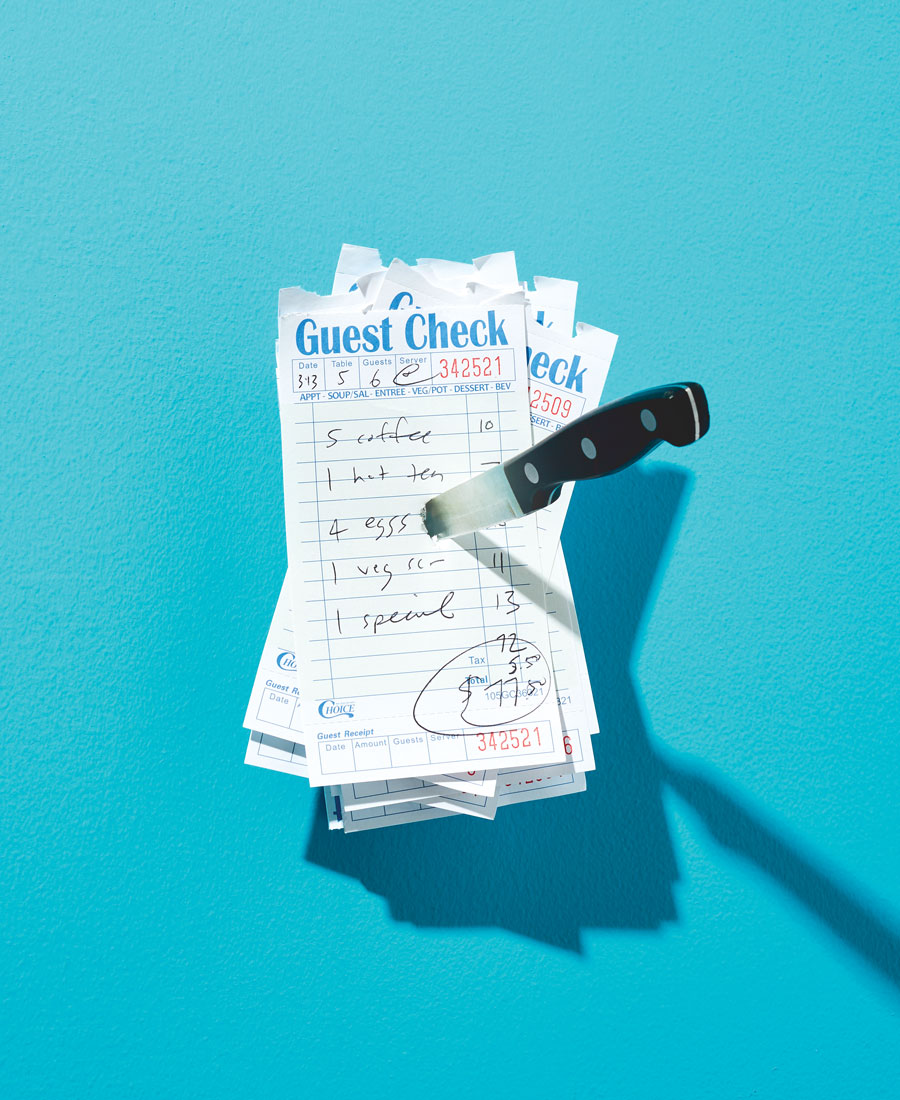

The coronavirus crisis has caused many restaurant closings — and created an opportunity for much-needed change. Photograph by Andre Rucker

Back in June, an Instagram account called @phillyfoodworkers appeared on my feed. No one’s name is attached to the profile, and the avatar is just a solid blue circle.

The bio reads, “Elevating the voices of Philly service industry workers,” and there’s a link to a Google form taking open submissions. It’s a strange account in that its aesthetic is very bright and happy (each post is a blobby color-blocked pattern superimposed with text), but the content it publishes is very much not:

I was told I couldn’t work somewhere because I am Black.

He proceeded to grab me by my ponytail, pulling my head downward and backwards towards the table and said, “I like this one. How do I get one?”

The chef/owner is absolutely a revered figure in the industry as well as to guests and “fans” of his restaurant(s) & cookbook(s). To the outside eye, he comes off as gregarious. But behind scenes he acts like a childish frat boy.

Each post contains a caption with a detailed account of specific transgressions experienced by the faceless voices behind the ’grams. No names are named, but sometimes we’re given a clue.

View this post on Instagram

Post after post, week after week, a meticulous and mysterious curator promising anonymity and masterfully revealing only enough information to propel the rumor mill has turned @phillyfoodworkers into the talk of the restaurant scene in the coronavirus era — maybe the only era in American restaurant history in which an account like this could exist.

Because the restaurant world in the Age of COVID is brave and new. In destroying the industry, the pandemic had two simultaneous side effects. It forced most owners to reevaluate their businesses (which, because of wafer-thin profit margins and an abundance of financial risk, walked too fine a line between utter failure and middling success). And it forced workers into their homes, out of their jobs, with nothing to do but bake sourdough bread and think about the inequities they’ve faced since entering the industry.

In Philly, this led to an entire summer of restaurant workers — some recently laid off, some still employed — organizing and forming coalitions to advocate for better working conditions. In West Philly, former employees at Dock Street Brewery, known as the Dock Street Workers, picketed outside the 50th Street brewpub, demanding a restructuring of the business model upon their return to work. The Organized Collective of Concerned Employees of Safran Turney Hospitality (which is the restaurant group behind Barbuzzo, Bud & Marilyn’s and Little Nonna’s) submitted a letter to the ownership (Val Safran and Marcie Turney) requesting, according to a report by Forbes, “a fair hiring system that includes better COVID pay and protection, more communication from management and the establishment of a human resources position.” Right about the time that Rich Landau and Kate Jacoby prepared to reopen their vegan bar V Street, the V Street Workers, a coalition of former and current employees, organized with their own list of demands: Pay out accrued sick pay; bump up the hourly wage to $20 per hour plus tips for both front- and back-of-house workers; and “actively work to dismantle white supremacy within the restaurant group.” (According to the workers, there were no managers of color and no Black front-of-house workers at V Street.) Landau and Jacoby responded in an email: “We agree that the restaurant industry is long overdue for meaningful change on many levels. However, due to the devastating effects of the pandemic on the business, we must let you know that we are in no position to continue this conversation at this point in time. … Consequently, we are saddened to tell you that we will be unable to reopen V Street.”

It wasn’t too long ago that racism, sexism, abuse, and worker exploitation weren’t just tolerated and encouraged in restaurants; they were cause for celebration — romanticized by industry leaders (who are, more often than not, white men) and willfully ignored by the media that covered restaurants in critical capacities. Of course, there were workers and writers who spent the better part of the past decade exposing the filth and raking the muck. But the industry as we know it wasn’t built for exposés.

The industry as we know it was born in the shadows, nurtured by a commitment to opaque business practices and worker exploitation hidden behind a veil of supposed culinary artistry, badassery, and a low barrier to entry. (It’s one of the few American businesses that will hire the undocumented, the previously incarcerated, and those without formal educations.) For the past century, restaurants thrived in the shadows. But they could only thrive in the shadows. The less we knew as diners, the better business was.

When the media caught on to the fact that restaurants and chefs contain multitudes — that they’re powerful agents of culture and history and community (which makes for great stories) — the industry began taking itself more seriously. In a New York Times Magazine piece published back in April, a month after restaurants went dark across the country, acclaimed chef and author Gabrielle Hamilton recounted how restaurants evolved — unsustainably — into more professional workplaces: “The ‘waiter’ became the ‘server,’ the ‘restaurant business’ became the ‘hospitality industry,’ what used to be the ‘customer’ became the ‘guest,’ what was once your ‘personality’ became your ‘brand,’ and the small acts of kindness and the way you always used to have of sharing your things and looking out for others became things to ‘monetize.’”

But in the United States, “professional workplaces” provide employees with benefits. “Professional workplaces” have employees who are paid an honest-to-goodness living wage. “Professional workplaces” typically don’t operate on single-digit profit margins (and if they do, they surely wouldn’t be considered successful), and they’re filled with policies and HR departments that at least try to combat workplace toxicity. “Professional workplaces” are given government relief during global pandemics. Restaurants, traditionally, do, have and get none of those things.

The unnatural professionalization of an inherently unprofessional industry would eventually be what brought it to its knees. And then the pandemic came along and made it beg for its life.

So here we are in what is clearly a watershed moment. As of this writing, some of Philly’s greatest restaurants haven’t reopened; others have closed for good. Many are still on life support, doing takeout, impatiently waiting out the pandemic’s stay. Owners and workers are in purgatory, reckoning with their pasts and uncertain of their futures except for the inevitable: Restaurants, on an operational, cultural and economic level, will change. They have to.

On June 15th, Martha, the popular locavore bar in Kensington, reopened with a revolutionary (by Philly standards) new business model: a 20 percent service charge added to each check in lieu of a tip. The change, according to co-owner Jon Medlinsky, allowed for the expansion of health-care coverage for employees and a more equitable pay distribution. Since the food menu is made up of sandwiches, salads and snacks, employees at Martha are able to switch seamlessly between the front and back of the house. The restaurant of the future might look like Martha.

Typically, non-management front-of-house positions (servers, bartenders, bussers and barbacks) are paid a sub-minimum wage called the “tipped wage.” In Pennsylvania, the minimum tipped wage is $2.83 per hour. Owners who can afford general managers (in Philly, that’d be the bigger groups, like Starr Restaurants and the Schulson Collective) pay them a salary. Back-of-house positions (line cooks, dishwashers, porters) are either paid at least the state minimum wage ($7.25 per hour) or given salaries, depending on experience and the way the business is set up. Tips aren’t typically shared between the two houses, and the pay disparity between them complicates everything. So does the fact that most restaurants, especially smaller ones, don’t provide workers bare-minimum benefits like health insurance.

In an eight-hour shift, a Philly server is paid about $23 by his or her employer (much of which goes to taxes), and remaining income is in the form of tips. Essentially, owners rely on guests to pay their employees. In some of Philly’s most popular restaurants, a server could average around $300 in tips a night. Cooks don’t even come close to that kind of money despite working in incredibly difficult conditions. Dishwashers often make less than cooks. Some of them — mostly undocumented workers, because of their status — make less than minimum wage, under the table, in cash.

So here we are in what is clearly a watershed moment. As of this writing, some of Philly’s greatest restaurants haven’t reopened; others have closed for good. Many are still on life support, doing takeout, impatiently waiting out the pandemic’s stay.

Worker exploitation is baked into the model of a business that operates with such thin profit margins, though it goes even deeper than that. Tipping culture, born in Europe and imported here, entrenched itself after the Civil War, when hospitality-business owners found ways to avoid paying workers, many of whom were former slaves and immigrants. “We may live in a very different society from 150 years ago, but the sub-minimum tipped wage still exacerbates the inequalities passed down from that time,” William J. Barber II wrote in his history of tipping in America for Politico. A 2018 data-charged Eater report concluded that tipping “encourages racism, sexism, harassment, and exploitation.”

There’s a notion that eliminating tipping will lead to a decline in service and talent pool shrinkage, but there’s plenty of scholarly evidence to refute that. In 2015, New York restaurateur Danny Meyer — the man behind Shake Shack, Gramercy Tavern and Union Square Café — eliminated tipping in his restaurant group in an effort to spur change in the industry. In Philly, we’ve seen a few no-tipping restaurants open over the years. (Girard, a bruncherie in Fishtown, is the most notable.) One Fair Wage and the Restaurant Opportunities Center United advocate for the elimination of the tipped wage nationally. (They were successful in their efforts on the West Coast.) But the restaurant industry is slow to change, mostly because owners — who launch businesses that make little money with very little capital — aren’t incentivized to change. And the ones who do can have middling success reverting to the old model: In response to the pandemic, Meyer reimplemented tipping in his restaurants for outdoor dining. “We’ve come to believe that it’s the inability to share tips that is the problem, not the tips themselves,” he wrote in his announcement.

So now we pray for Martha’s survival, and for the survival of all the restaurants that follow its lead.

Scott Schroeder has disappeared. You might remember him. He was the chef and co-owner of Hungry Pigeon in Queen Village. And then, all of a sudden, he wasn’t. He was very active on social media, touting his sometimes divisive political views with aplomb. He gave great interviews to the press, and his candor provided a much-needed sense of humanity in an industry that’s so often driven by PR. He was as vocal and forthcoming as a chef can be. And then, all of a sudden, he wasn’t.

Back in June, the civil uprisings in Philadelphia that followed the murder of George Floyd prompted business owners across the city to state their support, and sometimes disdain, for the cause. Schroeder posted a series of stories on his Instagram. One read: “Looting, rioting, and setting things on fire is dumb. Seeing people of all colors and ethnicities standing up against the police state is absolutely fucking beautiful though.” Another: “Thank you Black America. You had me at hip hop and fried chicken.”

That Instagram story, it seems, was the beginning of the end of his chef career. In the days that followed, several laid-off and former Hungry Pigeon staffers published a letter on Medium denouncing the chef’s “anti-black rhetoric as well as his recent lashing out at former employees who have directed legitimate criticism at his business practices and his behavior on social media.” The restaurant sat empty, collecting letters and signs from neighbors who shared the same sentiment. The wooden bench outside was tagged: “Scott Schroeder — owner of Hungry Pigeon — is a racist!!”

Schroeder apologized to his staff in an email and announced that he’d be leaving the restaurant permanently. “I’m not going to pursue a chef job either,” he wrote. “I’m going to think about all of this and what you have said and make a change. Including taking sensitivity training before I am anyone’s chef again. I have heard you and do not take this lightly.”

And then, poof. Gone. Hungry Pigeon reopened for takeout and outdoor dining in mid-June, but Schroeder isn’t part of it anymore. (His former partner, Pat O’Malley, is the sole owner.) He’s no longer on social media; he’s no longer publicly opining about restaurants. And as the foodie gaze awaits its next victim, Schroeder becomes just another chef lost to a massive cultural reckoning that was decades in the making.

“Imagine we let restaurants exist the way we let hardware stores exist,” food and culture writer Alicia Kennedy wrote in her weekly newsletter. “Has there ever been a rock star garden-hose expert, a celebrity buyer of hammers and drills? I’m sure there is a niche magazine dedicated to these professions, but they’re not given endorsement deals or TV shows. Maybe they deserve them.”

Photograph by Andre Rucker

It’s a concept I’ve been contemplating for as long as I’ve been writing about chefs and restaurants professionally. I think about it every time a chef is exposed as a sexual predator or a racist. Every time Marc fucking Vetri tweets to his 30,000 followers about wanting to reopen his dining rooms in the middle of a pandemic, I feel a pang of regret. I, like so much of food media, helped to create a monster — not the chefs themselves, but the culture that surrounds them and gives them so much power.

For the past 20 years, the places that gained any sort of recognition tended to be built to European standards, from the style of service in the front to the kitchen brigade in the back. The kitchen brigade is hierarchical. It gave us those fancy French titles: chef de cuisine, sous-chef, saucier, etc. And the kitchen brigade, we’re realizing now, is an inherently flawed system. Flawed because it functions under a faulty cream-rises mentality that holds that the most talented and hardest-working will be hired and promoted. (As we’ve seen time and again, cream doesn’t always rise in an ism-infected society like ours.) It’s flawed because the kitchen brigade, and all the forms it took in our restaurants, always has a head chef running the show — and those chefs, for whatever reasons, became American royalty. The faces of the industry. They garnered branding opportunities for their businesses and provided potentially viral stories for magazines and blogs.

We, the media, heralded the chefs as geniuses. We gave them their own TV shows and book deals and magazines. We pitted them against each other in season-long battles royal on the Bravo network. We made them out to be wizards behind curtains, artists with shiny new platforms to express their creative work — even if that work sometimes meant Columbus-ing cuisines (see: Jean-Georges Vongerichten) and sexually assaulting women (see: Mario Batali).

“Celebrity chefs and food writers need each other — to build their brands and ‘do numbers,’ whether online (for the writers) or at the point of sale (for restaurants),” Kate Telfeyan wrote in the New Republic. “The food media is complicit in the creation of kitchen tyrants, building their profiles, massaging their egos, exploiting their personalities for clicks — and chefs, in turn, help elevate the careers of food writers with access and exposure. In this sense the food world represents the marriage of two uniquely flawed industries: restaurants and the media.”

Sally, a natural-wine and pizza restaurant owned and built out by the folks behind — surprise, surprise — Martha in Kensington that will eventually open in Fitler Square, is taking an unorthodox approach to the restaurant model.

“We are at the early stages of what this wants to be,” says Cary Borish, a co-owner in the project. “But we’re trying to be really thoughtful about it. How can we pay a livable wage? How can we use the restaurant in a way that it’s more than just a restaurant, in a way that it’s a model for other restaurants, whether it’s being transparent about the P&L, or whether there’s equality in the hierarchy of the restaurant, whether there’s respect for all employees? That’s the challenge.”

Sally’s chef, Rob Marzinsky, tells me: “I’m building a small core management team with my ‘pizzaiola,’ Anna D’Isidoro, and our beverage director, D’Onna Stubblefield. It’s all very collaborative, a lot of sharing of responsibilities, with an eye on the same goals and values. All equal, no hierarchy. Almost like a co-op.”

It’s a revolutionary perspective as far as restaurants go; typically, employees carry out the vision of the owner. But at Sally, I’m told, there won’t be any one person running the show, no one face of the restaurant.

“We’re very aware of the power dynamics that exist between owners and staff, and we’ve been having many meetings, long meetings, about finding balance,” says Borish. “How do I — as the white guy at the table, the owner — not have all the power? How do I share that? How do I harness it in a way that gives everybody a voice, where everybody feels heard?”

As far as how the team applies its vision … well, we’ll have to wait and see. We’ve watched too many do-good restaurants fail in this city. But Marzinsky is hopeful: “I think restaurants can be sites of bases of community outreach and social justice. We can spread awareness, boost voices, and make pizza, too.”

The restaurant of the future might look like Sally.

Restaurants, we sometimes forget, were put on Earth to make money — which is a terrible thing to say about restaurants, isn’t it? All that talk of community, the passion for hospitality, the friendships formed between chefs and farmers, the excitement about morel mushrooms in spring, the birthday celebrations, the clinking of glasses by candlelight — it’s easy to forget that it’s all part of a machine designed to fill the owners’ and investors’ pockets.

In March, restaurants in Philly and beyond stopped making money. The city (rightly) shut them down to keep citizens from gathering indoors without masks. Of the 701,000 U.S. jobs lost in March, 60 percent were industry workers. The federal government came up with a $2 trillion relief package to salvage what it could, but it ultimately fell short for independently owned restaurants, specifically. Owners across the country organized, forming groups like the Independent Restaurant Coalition, headed by celebrity chefs including Tom Colicchio and José Andrés. Smaller city-specific coalitions formed as well: In Philly, we saw Nicole Marquis, owner of HipCityVeg, launch Save Philly Restaurants. These affiliations were created for the purpose of lobbying for expanded protections and additional funding.

In the meantime, restaurants are dropping like flies. Some in Philly didn’t even make it past May. “Without substantial governmental intervention to save small businesses and the jobs they create, plus a coherent national policy to combat the contagion’s spread, we’re all doomed,” Le Virtù owner Francis Cratil-Cretarola wrote in an op-ed for the Inquirer.

In the days following the government shutdowns, New Orleans-based writer/activist/artist/cook Tunde Wey published an essay on Instagram. In it, he argues against a government bailout: “An industry where labor is segregated by race and gender, underpaid and uninsured. An industry fed largely by a hyper-commercial agricultural system that either extracts profits from the environment with little consequences or offers ethically sourced produce to just a few for a lot. Let it die. An industry where on the higher end is great food at fat prices in spaces that drive up real estate values, pushing property prices higher and poorer people further. And on the lower scale, working poor people, making barely enough to keep them going, serve low nutrition meals to other working poor people, who can’t afford quality housing because of predatory development that supports new restaurants. Let it die. And all over the spectrum, a white man gets paid off of all of that. Let it die.”

As much as it pains me, I can’t help but think that letting it die might actually be the solution. For the restaurant industry to really change for the better — inside and out — it has to detach itself from a capitalist machine that’s contributed to so many of its failings. The only way for businesses — in this country, at least — to detach would be to close. Anything less would require owners to give up more than they already have. It would require that they make even less money than they already do, to pay for health care (which should otherwise be universal and free). It would require an internal structure that’s without hierarchy, without ego, without discrimination. It would require a sense of professionalism and substantial governmental support in times of need — all of which goes against the grain of the free market.

Right now, it seems the federal government has given up on the restaurant industry, leaving it to rot in place while continuing to bail out the industries it’s deemed more essential. And the future-thinking owners who are attempting to create more equitable workplaces? They’re trailblazers. Trailblazers in business have a hard time under regimes that value and prioritize the status quo.

The restaurant of the future might look like Martha. It might look like Sally. But right now, the restaurant of the future doesn’t seem to be a restaurant at all, just an empty plot of land — a pile of rubble still smoldering from the devastation of a global pandemic. The government continues to ignore it, its guests are at home eating takeout, and there’s nobody left to write about it. For better or worse.

Published as “The End of Restaurants” in the September 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Philadelphia magazine is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and economic mobility in the city. Read all our reporting here.