Cooking The Books: New Cookbooks from Vetri and Vongerichten

There are two kinds of cookbooks: the ones best read beginning to end, and the ones that make more sense in the other direction. (This leaves out the largest category—those not worth reading at all—but I’m not here to waste your time reviewing those.)

Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s new Home Cooking with Jean-Georges: My Favorite Simple Recipes, is best begun on page 252. That’s where the renowned New York chef and restaurateur lays out the keys to his pantry: about a dozen ingredients that fall outside the “easy-to-find” staples that predominate in this book’s simple recipes—and the ones that distinguish Vongrichten’s pretty volume from its coffee-table cousins.

Start the book at the beginning and you’ll soon be asking yourself: Nicoise Salad with Sun-Dried Tomato Vinaigrette…Crisp Savory Roast Chicken…Shrimp Salad with Champagne Beurre Blanc. Why do I need another cookbook with all these same old recipes?

Start with the pantry section, though (and then backtrack to page 244, where Vongrichten outlines his somewhat misleadingly titled “Basics”) and you’ll have your answers. In no particular order, they include kecap manis (a palm sugar-sweetened soy sauce that’s a staple condiment in Indonesia), konbu (dried kelp, a staple in Japan), mustard oil (India), and yuzu juice (back to Japan).

What’s odd—but winning—about this cookbook is that most of these items appear only once or twice in preceding hundred or so recipes. And those appearances are concentrated in Vongerichten’s so-called basics, like his smoked chili glaze (with passion fruit puree and kecap manis) or his Russian dressing (with white miso). So the recipes are pretty much as easy as they sound, but contain just enough subtle twists to keep you engaged. That Nicoise salad carries an unexpected whiff of elderflower cordial, for example, but the recipe is otherwise normal. That roasted chicken is brined with konbu—and, again, is otherwise normal. The shrimp salad? It gets its personality from Vongrichten’s house dressing, which is built on truffle juice, not the now-ubiquitous truffle oil.

I haven’t cooked all of these yet, but I can tell you that his soy-braised lamb shanks (flavored with Asian pears, lemongrass, star anise, champagne vinegar, and ginger) are dynamite, and perfectly tuned to fall. And pairing the dish with a bright duo of warm apple-jalapeno puree and cool apple-jalapeno salad was sneakily brilliant (Vongerichten’s suggestion)—not to mention a perfect excuse to serve this dinner with champagne (mine).

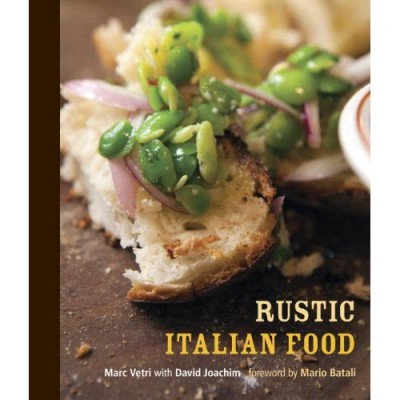

Marc Vetri’s Rustic Italian Food is a different beast. Here is a cookbook to start from the beginning. Aided by editor David Joachim, Vetri writes with verve, humor, and something of a chip on his shoulder. Right off the bat he comes out swinging—picking sous-vide as his first punching bag.

“You can vacuum-seal a veal medallion in plastic, label it, put the bag in a water bath at a prescribed temperature for a prescribed time, then take it out, cut it open, and serve it,” he begins. “Some people think that this kind of scientific advancement is a godsend. But not me. If I wanted to be a file clerk, I would work at an accounting firm. I don’t enjoy filing. I enjoy cooking.”

Vetri is by no means the first guy to recoil from this approach to cooking, and neither is he the first to make a case for traditional handcrafted food by writing a cookbook. But what distinguishes Rustic Italian Food from a lot of other sermonizing cookbooks is the nature of Vetri’s preaching. It’s short on pedantry, and full of stories with unexpected (or outright inscrutable) morals.

Here we have a portrait of Philadelphia’s Italian master as a young punk, smearing the contents of a perfect baguette sandwich all over a French shopkeeper’s window to protest the man’s effrontery. There we have the tale of Vetri smuggling an Iberico ham into the States in a linen box, shipped by FedEx for $800. Later he tells of shooting down his colleague Brad Spence’s homemade ladyfingers for the tiramisu at Amis by insisting that “if there’s one thing I learned in Italy,” it was that store-bought ladyfingers work better. Recalls Vetri: “He stood there with his mouth open like I’d just killed his dog.”

There’s a lot to learn from both Vetri’s commitment to the old-fashioned ways and his openness to figuring out easier ones. A case in point is his section on extruded pastas. Recalling his first attempts at drying homemade extruded pastas—which ended in cracked noodles—he describes the advantages of having “extensive rooms that dry the pasta slowly in an environment with precisely controlled humidity,” and then vouchsafes his own method: just leave the pasta uncovered in the refrigerator.

Much of the practical value of Rustic Italian Cooking lies in observations like these—and a decent number of truly easy recipes, like pork ragu with stone fruits, which took me all of 15 minutes of active cooking. But Mario Batali is spot-on in his foreword when he writes that Vetri’s latest “should in fact be placed in the ‘reference book’ category.” With instructions for everything from trussing a suckling pig to fermenting salami to making sausage out of fish, this book works as a hardcore DIYer’s companion to Marcella Hazan’s Classic Italian Cooking.

Those two are now side-by-side on my shelf, and I have a strong feeling that I’ll be turning to Rustic more often in the coming months. It promises to be a rich stretch of cooking. Vetri’s egg pasta calls for twice as many egg yolks as Hazan’s (nine for less than two cups of flour!), and his recipe for veal cannelloni with porcini béchamel has autumn written all over it. So does the gnocchi with oxtail ragu, from Amis. Then there’s winter, which will mean the fig and chestnut bread. Might need to serve that alongside my mom’s chestnut soup for Christmas dinner. By which time the big-hearted among you will have given this book to whoever gave you Thomas Keller’s Ad Hoc last year.

Rustic Italian Food [Amazon.com]

Home Cooking With Jean-Georges [Amazon.com]