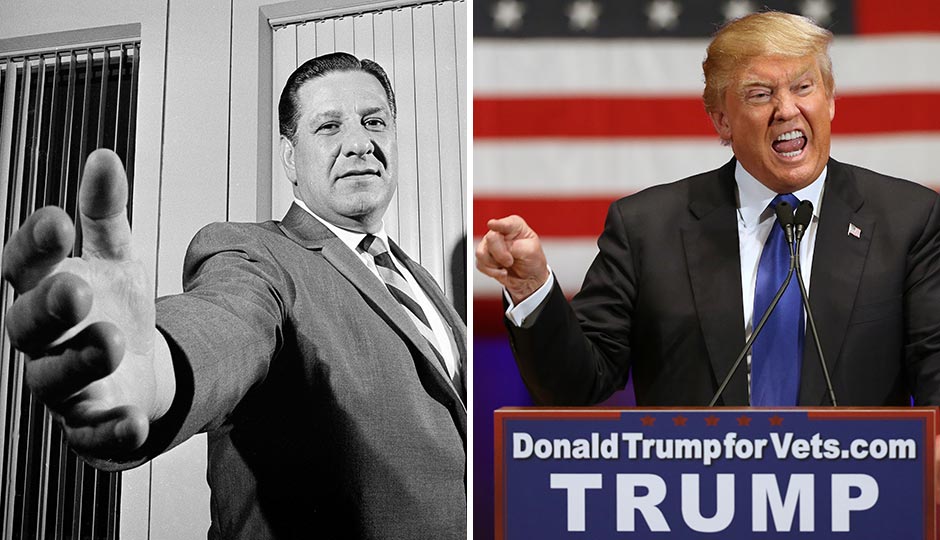

Donald Trump Is Frank Rizzo, Reborn

Frank Rizzo, 1968, and Donald Trump, 2016. Photographs by Bill Achatz and Andrew Harnik, Associated Press

Rocco DiSipio is a small-business owner in a working-class neighborhood where times aren’t quite as good as they once were. He isn’t used to being interviewed by reporters, but it’s primary season, and journalists want to know what the man-on-the-street thinks of the brash conservative candidate who seems to do everything wrong — and keeps winning anyway.

“This election has some racism,” admits DiSipio, acknowledging that his candidate can be blunt, or worse. His pick doesn’t have the typical qualifications, either, but for DiSipio, that’s part of the appeal. “He’s going to stand behind his word if it kills him. He can flunk at it, but you can’t say he won’t try.”

Traditional elites and professional politicians are baffled that such a man could rise so high in the polls. He defies political conventional wisdom at every turn, flouting party leaders and blithely dropping quotes that would wreck any other campaign. “This is not a normal election,” a Republican operator tells a Washington Post reporter. “All normal voting patterns are out the window.”

This sounds like a dispatch from the Republican presidential primary campaign, and the candidate sounds a lot like Donald Trump.

But the quotes are actually from Philadelphia circa 1971, a time when a big bloc of the city fell for a different candidate who radiated authority and charisma — someone who would take charge and tell things as they were. That candidate was Frank Rizzo, whose unpolished tough-guy bravado, labor-friendly conservative populism and strident appeals for law and order spoke directly to the concerns of struggling working- and middle-class whites. Today, Donald Trump makes a very similar case to very similar voters.

Both men are known for their outsized personalities, unfiltered rhetoric, hatred for the media and utter assurance in their own righteousness. Both weaponized calculated bursts of invective: Rizzo promised to “make Attila the Hun look like a faggot,” while Trump assures his fans that he’ll “bomb the shit out of ISIS.”

Both placed themselves above other politicians as a breed apart, tougher and more genuine. “I have high principles — stand for good,” Rizzo told Newsweek in 1971. “If anybody gives me a bloody nose, I’ll wipe it off and just love to mix it up. My strategy is to be Frank Rizzo. No glib talk. No talking with forked tongue for Frank Rizzo.” Forty-five years later, Donald Trump is leading the Republican field. “I’m the only one that speaks my mind and tells the truth and everybody knows I’m right,” the magnate told a Fox News anchor last year, after his comments about temporarily banning Muslims from the United States. “You know what my campaign strategy is? Honesty. I say it like it is.”

Rizzo tucked a nightstick in his cummerbund, and working-class white Philadelphians swooned. Trump pounds out 140-character insults on Twitter — his enemies are “failing,” “grubby,” “low-energy” losers/phonies/dummies — for similar effect. “Both those guys are just saying what everyone else is thinking, what the average American is thinking,” says Diane Gochin, 58, who backed Rizzo when she lived in the city and supports Trump now. “With Trump, as with Rizzo, he is not bound by the bar association or the banks or anything else,” says Gochin, who now lives in Montgomery County but grew up in Northeast Philadelphia and worked in the vast bureaucracy of Thomas Jefferson hospital. “He’s the best bet we have for bringing the common people back into government.”

IN AN OCTOBER National Journal article, longtime political reporter John B. Judis dusted off some sociological research from the 1970s that had been published in the book The Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of Alienation, by Donald Warren. Warren conducted surveys of large groups of white voters and identified within them a voting bloc he called Middle American Radicals (MARs). Their ideology, as Judis describes it, “revolved around an intense conviction that the middle class was under siege from above and below.”

MARs were distrustful of big business, and they favored some economic policies well loved by liberals, like a robust minimum wage and job guarantees. But they were also bitterly opposed to welfare and affirmative action and deeply suspicious of the federal government. Another hallmark: More than any other group Warren studied, MARs thought Washington, D.C., works best “when one person is in charge.”

Voters like these have been around for generations. They were supporters of Alabama governor George Wallace, who ran for president on a platform that promised law and order, repeal of civil rights advancements, and a robust system of social insurance. (Wallace told Newsweek in 1972 that if elected, he’d consider making Rizzo the director of the FBI.) In more recent years, some have backed Ross Perot or Pat Buchanan. But they’ve never amassed enough numbers to pick a major-party presidential candidate.

In the 1970s, big U.S. cities were packed with malcontented working-class white voters. Rizzo wasn’t the only conservative populist elected mayor of a big city. But none of them caught on nationally.

Trump obviously has. And that’s partly because large numbers of white Americans are gripped now by the same anxieties that troubled Rizzo’s base. In the early 1970s, most of America was still enjoying the broadly shared prosperity of the postwar Golden Age. Philly, though, wasn’t. By 1972, there were only 142,300 manufacturing jobs left in town. The city had shed a staggering 93,000 well-paying factory jobs in just 18 years. Property values were stagnant, and crime was on the rise. Between 1967 and 1970, the homicide count grew by 50 percent, and the number of reported robberies more than doubled. Working-class whites resented liberal do-gooders and capital flight on one hand, and on the other a growing African-American population that was demanding its rightful share of jobs, services and political power.

Those conditions created legions of Rizzocrats in Philly, and similar conditions help explain the Trump phenomenon today. By 2044, America will no longer be a majority white nation. That demographic shift is accelerating — and, it seems, becoming increasingly real in the minds of many white Americans. At the same time, wide swaths of the population have suffered declining living standards and stagnant wages, just as many Philadelphians did in the late 1960s. Manufacturing industries have been vaporized everywhere in America, not just the Midwest and the Northeast, plummeting from 17.3 million jobs in 2000 to 11.5 million in 2010. Both eras saw large numbers of working- and middle-class whites unsettled by rapidly changing cultural norms: the civil rights movement in Rizzo’s time, gay marriage and Black Lives Matter today.

Crime looms as one seemingly huge difference between America in 2016 and Rizzo’s violence-plagued Philly. “I specifically remember Rizzo because I lived in town at that time and I used to walk from the University of Pennsylvania to Society Hill, and it was safe to do so,” recalls Gochin. “When Rizzo was mayor, we had a cop on every corner, and he was very aggressive about keeping the city safe. That’s what I remember about Rizzo. The city was prospering. After he was gone, there would be these wolfpacks that would come out. I moved a couple years after that because it wasn’t safe anymore.”

Today, crime is at record-low rates across much of the country. Nonetheless, Trump has tapped into the same sort of racially charged security fears that Rizzo ran on. The real estate mogul has thrilled his supporters by smearing Mexican immigrants as “criminals, drug dealers, rapists, etc.” There’s a bright, easily traced line between Trump’s vows build an enormous wall on America’s southern border and Rizzo’s own peace through strength proclamations: “The only other thing we can do now is buy tanks and start mounting machine guns.”

As mayor, Rizzo organized a special police squad to spy on his opponents, hired hundreds of new police officers, and once circled the Inquirer’s loading dock with angry supporters, blocking delivery of the paper after it angered him. During the 1971 election, after the Democratic governor scrapped Pennsylvania’s death penalty, Rizzo mused, “Maybe we need a local option. Maybe we can have our own electric chair.” In another interview, he said the Black Panthers “should be strung up. … I mean, within the law.”

Trump has, if anything, appeared even less concerned than Rizzo with niceties like due process. After the Paris attacks, Trump told Yahoo News: “Some people are going to be upset about it, but I think that now everybody is feeling that security is going to rule. … And so we’re going to have to do certain things that were frankly unthinkable a year ago. … ”

In times of shared economic prosperity, figures like Trump and Rizzo fall flat. But when economic growth is unequal and uncertain, anti-immigrant sentiment and racial tension quickly come to the fore. “Every time you go through a period in which the bulk of American families lose a sense of getting ahead, certain kinds of problems start to appear,” says Harvard economics professor Benjamin M. Friedman, author of The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth. “This is about people worrying about their ability to get ahead and their position in the economy and the society.”

THERE ARE, OF COURSE, innumerable personal differences between Donald Trump, who grew up rich and privileged, and Frank Rizzo, the son of a rowhouse beat cop. But the nature of their political appeal is strikingly similar, not just because of what they say, but because of how they say it. Both figures “offer a populism of style,” says Timothy J. Lombardo, author of the forthcoming The Rise of Blue-Collar Conservatism: Frank Rizzo’s Philadelphia and the Politics of the Urban Crisis. “Trump plays this over-the-top and very masculine role. Same thing Rizzo did. People are unwilling to trust politicians of any stripe, but these guys don’t sound like politicians.”

Establishment Republicans and progressives look at Trump and see a reckless, narcissistic, even dangerous figure. Gochin, though, sees in Trump what she saw in Rizzo: the confidence and certitude to fight the necessary battles — against corruption in government, political correctness, globalization — and win.

“This is not the country I grew up in, and I’m not leaving this for my kids,” says Gochin. “Trump keeps saying this is all bullshit we’re seeing here. They’ve sent all our jobs out overseas. Everything is so screwed up here, it’s frightening. Before we are in total collapse, someone has to stick their neck out there. Trump, if he wins, he’s got the mouth, and he’s got brass balls.”

And Trump is now the favorite to win the Republican primary. Polls have him neck-and-neck with far-right-wing Ted Cruz in Monday’s Iowa caucuses, and Trump is way ahead in New Hampshire and South Carolina. In national polls, he’s doubled up on Cruz and is even further ahead of the rest of the Republican gaggle.

Can a populist conservative like Trump govern? Frank Rizzo’s record isn’t encouraging. Philadelphia lost a crippling 13.5 percent of its population during the 1970s. In Rizzo’s first four years, an estimated 980 companies and 41,000 jobs left the city. Rizzo signed off on the largest tax hike in Philadelphia history, which was needed in part because of his extravagant spending on the police department, municipal union contracts and patronage appointments. He even failed to drive down crime. There were 385 murders in his last year in office, 33 more than his first year in office. (The 2015 total was 280.)

But those are statistics, and they don’t reflect how many Rizzo voters, many no longer living in the city, remember his time in office. They remember instead that Rizzo spoke to them, and that he went to work every day intent on keeping them safe.

Published as “Frank Rizzo, Reborn” in the March 2016 issue of Philadelphia magazine.