Good Ol’ Facts Challenge the Ferguson Effect

Last May, the Wall Street Journal ran an article that would make one St. Louis police chief’s musings go viral.

The argument went like this: The death of Michael Brown—and the Black Lives Matter movement that followed—increased scrutiny of police officers across the country, which, in turn, spooked them into less aggressive policing tactics, which, in turn, led to a national crime wave.

If it all sounds speculative to you, that’s because it is. But unfortunately, the long-overdue, critically important conversation the country is having right now about policing means that sometimes half-baked ideas make their way into the public discourse. The theory quickly attracted the attention of politicians and journalists, who deployed critiques that ranged from the interested to the incredulous to the enraged.

During a speech at University of Chicago Law School, FBI Director James Comey said he thought that an increase in violent crime was, at least in part, due to a “chill wind blowing through law enforcement over the last year.” The Alantic’s David Graham called the Ferguson effect “the Bigfoot of American criminal justice: fervently believed to be real by some, doubted by many others, reportedly glimpsed here and there, but never yet attested to by any hard evidence.” Fellow Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates derided it as an “utterly baseless suggestion.”

Last Thursday, NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice produced some sorely-needed data analysis that finally disproved the idea that we’re all living in the middle of a countrywide crime wave.

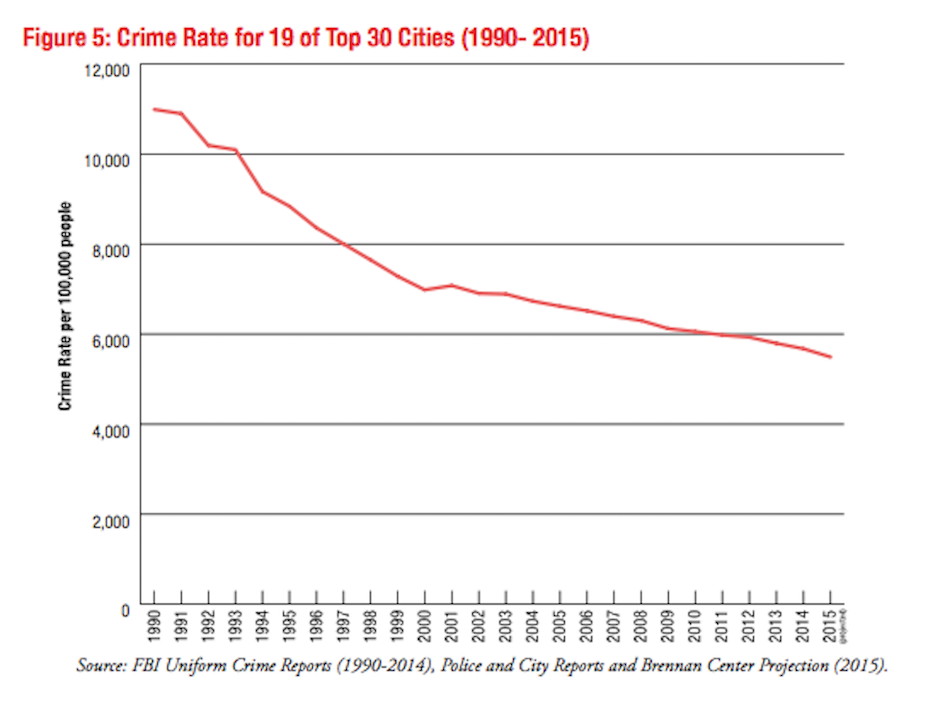

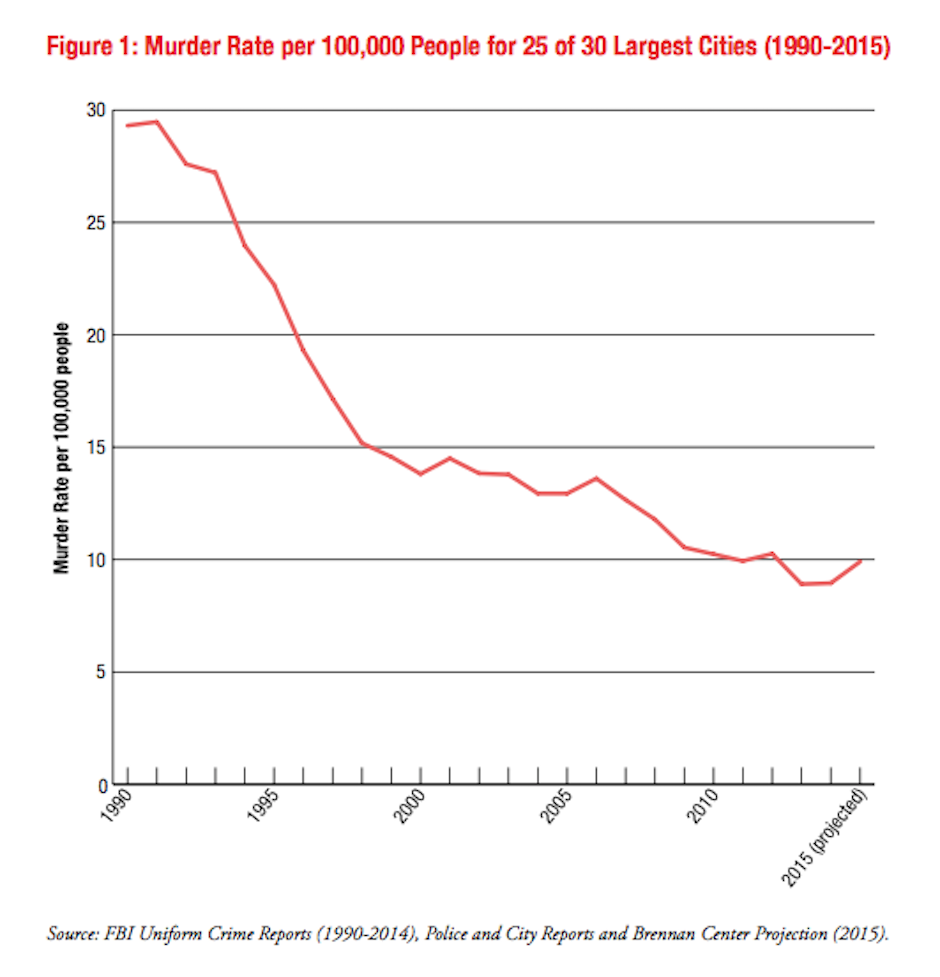

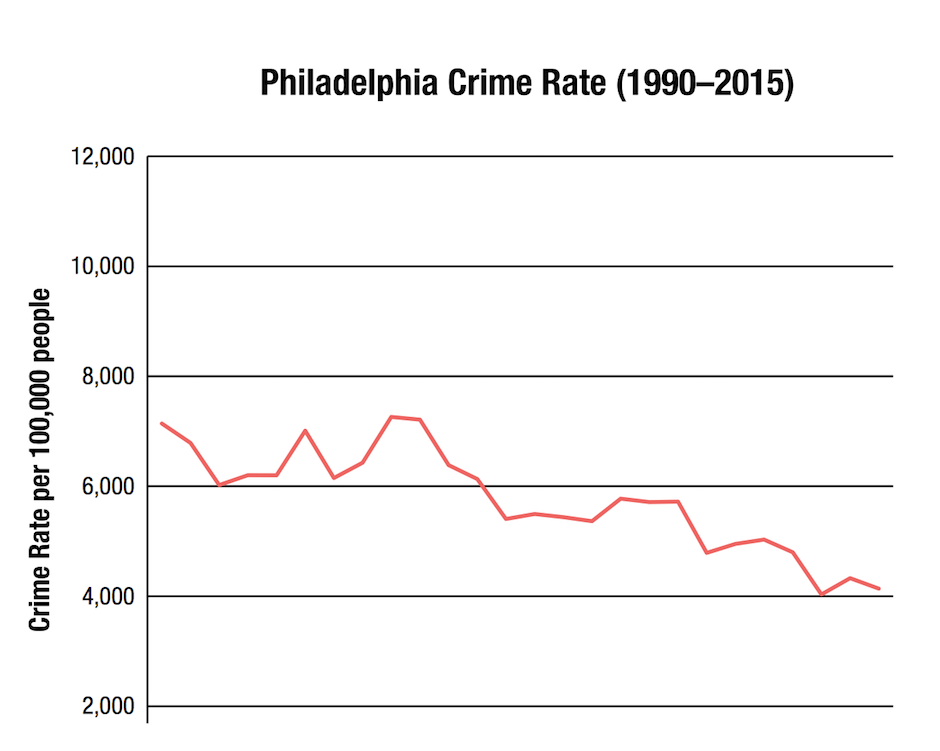

According to data the Center fielded from 25 of the top 30 biggest American cities, the U.S.’ national crime and murder rates have substantially decreased in the last 25 years. And while the data does forecast a small rise in the national homicide rate from 2014 to 2015, it’s important to note how that uptick fits into the broader historical narrative; that the surge doesn’t definitively foreshadow a continued climb or a plunge; and that to an extent, all of this is hypothetical anyway, given that the 2015 numbers are imperfect projections. (The report’s authors predict, for instance, that Philadelphia will see a 2 percent decrease in murders from 2014 to 2015, but according to the Philadelphia Police Department, we’ve already seen an increase, albeit a small one).

Approaching the Ferguson effect from a national perspective, rather than a city-specific one, makes no sense anyway, argues Jerry Ratcliffe, chair of Temple University’s Department of Criminal Justice. Policing practices vary widely from city to city, he says, citing the fact that, in Philly, every new officer out of the police academy does foot patrol, unlike most other police departments in the U.S.

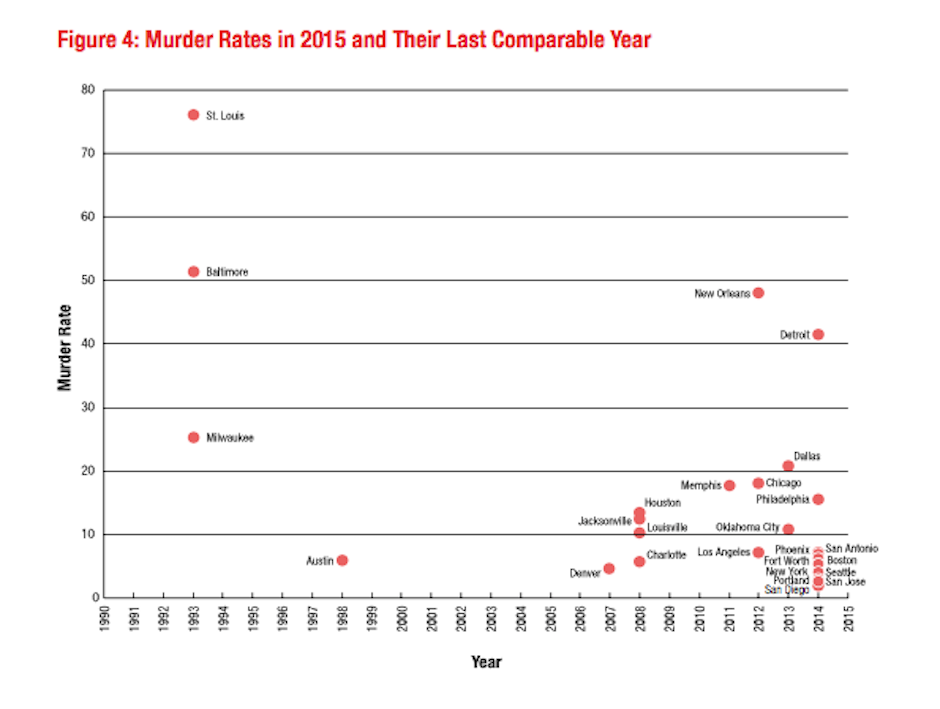

The Brennan Center data illustrates this point, showing that it’s actually a small handful of cities, including St. Louis, Baltimore and Milwaukee, that are grappling with historically significant murder rates. “Rather than a national pandemic, it appears that the increase in murder rates are localized, suggesting that community conditions are a major factor,” the report’s authors write.

Insofar as Philly goes, the report shows us what we already knew—that violence and homicides have seen a significant decline during Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey’s tenure. But there’s clearly still lots of work left to do when it comes to police-community relations. According to Ratcliffe, gathering more data would be a step in the right direction: “We’re the biggest city in the country that doesn’t do a police-community relations survey,” Ratcliffe says. “That would be very beneficial, if it was done well, in moving the police department forward.”