Philly Tops All Cities in Sending Juveniles to Prison For Life

Back in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that children who are convicted of murder cannot receive mandatory life-without-parole sentences because such laws violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. After the decision, some states not only prohibited the sentences for youths, but also applied the new rules retroactively. Pennsylvania was not among them.

Today, there are 214 people serving juvenile life-without-parole sentences from Philadelphia, according to a new report by the public interest law firm Phillips Black. That’s 9 percent of all juvenile lifers nationwide, though the city is home to only .5 percent of the U.S. population.

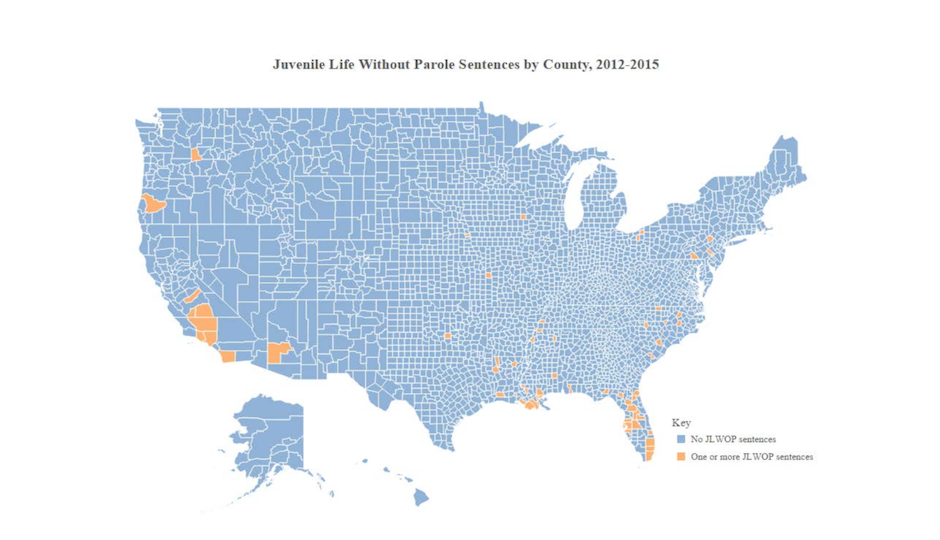

In fact, Philly is responsible for more juvenile lifers than any other county in the nation. And just five counties — Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Cook County, Ill., Orleans, La. and St. Louis, Mich. — imposed a quarter of the juvenile life-without-parole sentences currently being served in the United States. That’s a staggering figure. This map shows how stark the sentencing disparity is throughout the country:

Why are there more juvenile lifers from Philadelphia than anywhere else in the country? For a few reasons, probably:

- State laws. Since the 1920s, there have been two possible sentences for first-degree murder in Pennsylvania, according to the Juvenile Law Center’s Marsha Levick: mandatory life-without-parole or the death penalty. That means there have been decades for the state’s legions of juvenile lifers to grow. Levick said there is one juvenile lifer in Pennsylvania who was convicted all the way back in the 1950s.

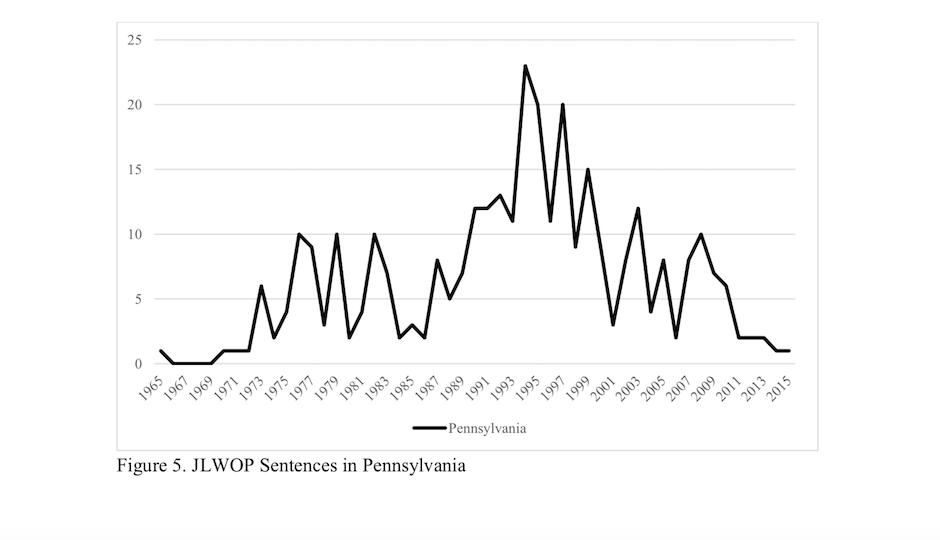

- More state laws (and fear-mongering). In 1995, Pennsylvania passed a law requiring all children charged with homicide to be tried as adults, no matter how young. “There is no minimum for which a juvenile could be charged with murder,” said Bradley Bridge, an attorney in the city’s public defender’s office. “Hence, we’ve had murder cases in Pennsylvania involving 9- and 10-year-olds.” Other states often have minimum ages before juveniles can be tried in adult court. According to the report’s authors, legislators approved this bill during the rise of the so-called “superpredator” myth. In 1996, Newsweek published an article warning of a ‘generation of teens so numerous and savage that they’ll take violence to a new level,'” they wrote. “A former Florida congressman warned subcommittee members to ‘brace themselves for the coming generation of super-predators.’ President Bill Clinton referenced in a speech these dangerous children whose ‘hearts can be turned to stone by the time they’re 10 or 11 years old.'” As you can see in the infographic below, the number of juvenile life-without-parole sentences skyrocketed in the 1990s.

African-Americans have been disproportionately impacted by Pennsylvania’s life-without-parole sentences for juvenile offenders. Blacks make up just 17 percent of the state’s general population, but 80 percent of its population of juvenile lifers.

- Tough-on-crime prosecutors. Until 2005, juveniles could be sentenced to death in Pennsylvania. Some prosecutors took advantage of that fact to negotiate plea bargains. “If you’re a prosecutor and you’re trying somebody for murder,” said Levick, “it doesn’t take a lot of thought to think that if you offered someone life in prison instead of death, you’re likely to get a guilty plea.” Lynne Abraham was Philadelphia’s district attorney between 1991 and 2010. She was dubbed “the deadliest D.A.” by The New York Times because she sought the death penalty so liberally. Abraham ran for mayor in the 2015 primary election and lost, in part because her criminal justice record was out of step with the times.

As if all that wasn’t bad enough, the picture in Philadelphia might be even worse than the report by Phillips Black suggests. Levick and Bridge said there actually are closer to 300 inmates who are serving juvenile life-without-parole sentences from the city.

Juvenile lifers from Philadelphia do have something to hope for, however. Next month, the U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in Montgomery v. Louisiana, which will determine whether its previous 2012 ruling ought to be retroactive. If judges decide it ought it to be, hundreds of inmates from Philly would be re-sentenced.