Wharton Prof Says VCs Keep Women-Led Startups From Raising More Money

Wharton management and entrepreneurship professor Laura Huang. Courtesy photo.

It’s 2017 and the gender gap in venture capital funding is only widening by the minute. Last year, venture capitalists invested $58.2 billion in male-led startups, while women-led companies received a paltry $1.46 billion in comparison. To put it another way, women own 38 percent of businesses in the U.S. but only get about 2 percent of all venture money.

Why? Some claim that that gap exists because of a lack of female VCs—the venture capital world is still largely a boys club that women just can’t access. Others even pin the gap on female entrepreneurs themselves—they’re simply not asking for enough. But new research from Wharton management and entrepreneurship professor Laura Huang, published in the paper “We Ask Men to Win & Women Not to Lose: Closing the Gender Gap in Startup Funding” suggests that the gap exists because of something venture capitalists do.

After observing Q&A sessions between 140 prominent venture capitalists and 189 entrepreneurs at the annual TechCrunch Disrupt — New York’s premier startup funding competition — Huang and her colleagues recognized that venture capitalists posed different types of questions to male and female entrepreneurs. Following the observations, the study tracked all funding rounds for the startups that launched at the competition and found that the male-led startups raised five times more funding than female-led ones.

According to Huang, the difference in questioning is one big reason why women-led companies get less funding than companies launched by men. BizPhilly chatted with Huang to learn more about her research and what it all means for female entrepreneurs and venture capitalists.

BizPhilly: What moved you to explore why female entrepreneurs raise less funding than their male counterparts?

Huang: I’ve been studying entrepreneurship and this aspect of meritocracy for a while and have had the chance to observe people—women, immigrants, people of color—who have faced glass ceilings and other disadvantages. A lot of them would leave these organizations to start their own companies, thinking they wouldn’t have to deal with disadvantages in the entrepreneurial space. Or so they thought. Once they enter entrepreneurship they still face biases and disadvantages. My research sees to uncover exactly what’s happening and why those biases exist.

BizPhilly: And how’d you land on this specific study that looks at how venture capitalists interact with female and male entrepreneurs?

Huang: This specific paper came out of a discussion with my co-authors around explicit and implicit bias. In entrepreneurship, when investors are choosing whether to invest, they’re thinking, “there’s a lot of risk in this.” There’s always a checklist of things that they’re feeling uncomfortable about, so they try and ask questions to get clarity and do due diligence.

That was the initial conversation we had, then we thought that it seems the women entrepreneurs are getting asked different type of questions. And if they’re getting asked different types of questions, might it be that when they actually respond to these questions they don’t have the opportunity to check off those boxes to help investors feel good about making an investment? That’s how we started embarking on this research and trying to figure out if there’s actually a difference in the questions men and women get asked, and whether it matters.

BizPhilly: What was your overall finding?

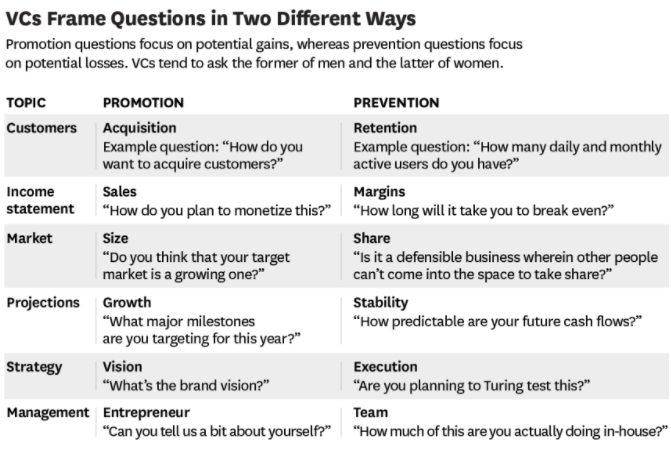

Huang: The finding is that men and women are getting asked different types of questions. Men are asked questions that are promotion focused like “How big could this opportunity get?” and “Can you tell us about the potential for success and the opportunity behind this?”

Women are asked prevention-focused questions, which are like, “This seems risky. How do you prevent against…” So investors don’t get the same glimpse of these women-led firms and male-led firms.

Graphic courtesy of Laura Huang.

BizPhilly: How has this finding been received?

Huang: A lot of naysayers have said, “Well, obviously. Perhaps women just have worse businesses, right? And so they’re going to get asked questions that are more about risk, because they seem like riskier companies.” But if you look at the study closely, we were actually very careful about that in particular. For our second study we experimentally looked at men pitching and women pitching the exact same company. So there are no differences in objective quality. We found that the same thing occurs. Women get asked questions about risk and prevention, and men get asked about opportunity. So it’s just not the case that the questions are based on the quality or type of company. They’re based on the entrepreneur.

BizPhilly: What could be driving this?

Huang: There are so many implicit signals that drive why men and women entrepreneurs get asked different questions. For one, entrepreneurship is seen as a male-type endeavor. There’s research that shows that when we think about entrepreneurs or try to picture what an entrepreneur looks like, the majority of investors think of men in a tech company. I think that’s driving a lot of what’s happening.

BizPhilly: The study also counters the common idea that the more female VCs we have, the more funding female entrepreneurs will be able to raise. We’re now realizing that we do have more female VCs now, but the funding gap is only widening. Can you say more about this?

Huang: There are a couple of things here. The first is that we just don’t have a lot of VCs that are women. So it’s going to take us a long time to get gender parity. The more women we can bring into VC the better. The second thing is whether you’re a VC who’s male or female, it’s important to recognize that there are implicit biases driving questions to entrepreneurs. There’s a difference in how they treat female and male entrepreneurs. VCs need to be aware of this in general.

I do believe that having more women represented in VC brings a lot of positives. It could be that there are more mentors and women that entrepreneurs can look up to and feel comfortable with. But in this particular instance, it’s important to remember that it’s not just about bringing in women mentors, and it’s not just about bringing in women VCs for funding. Having more female VCs can’t be the silver bullet because there are other things like our research’s findings that we all should be aware of.

BizPhilly: Your research suggests that entrepreneurs can train themselves to answer questions in a way that’s promotion-oriented as opposed to prevention-oriented. Can you talk more about that?

Huang: Yes, in our research we found that when you’re asked a prevention-focused question, you’re much more likely to answer in a prevention-focused way. This exacerbates the harmful effects. If you’re asked a promotion-based question you’re much more likely to answer in a promotion-based way. That’s a win-win because you’re able to answer in a way that makes you seem ambitious. For entrepreneurs who are asked prevention-based questions, they should be aware of this. They should work to redirect the conversation or put a pause on the prevention line of thought. They should switch the conversation so that it’s more in their advantage.

BizPhilly: Why does this burden to redirect the conversation fall on the entrepreneur as opposed to the VC?

Huang: I don’t think the burden should rest exclusively on the entrepreneurs. There’s a place for VCs to work against this. There is a lot more awareness as we go forward, but fact of the matter is, we can’t force VCs to be fair. We can’t force people who have the resources we rely on to care and be meritocratic. We can encourage them and perhaps make training around this part of the industry, but at the end of the day, if you’re an entrepreneur seeking resources and you’re facing all these glass ceilings, some of the burden does fall on your shoulders. This is unfortunate, and I think the burden needs to fall more on the investor’s shoulders, but reality is that it goes both ways.

BizPhilly: Looking ahead, how can we get entrepreneurs to even realize that promotion and prevention based questions are something they should be prepared for?

Huang: I don’t think these ideas just exist in the venture capital world. It’s about realizing that these things are pretty pervasive. In any context, the way we start off conversations, the way we begin asking people questions can really turn the entire conversation in a direction that leads somebody to have an advantage or a disadvantage. This happens in hiring decisions and interviews and in workplace relationships with senior colleagues.

Follow @fabiolacineas on Twitter.