Philly Rebooted: The Biggest Ideas of 2016 — and Beyond

Photography by Gene Smirnov

Something happened when Philly got the start-up bug: The idea that things could be reinvented, that business didn’t have to work as usual, that the old rules could be thrown into the Schuylkill — you know, innovation in the broadest sense — crept all the way up to the C-suite. Those bosses, in turn, made bold thinking the new way to do business in Philly. Here, brilliant local minds share their big ideas.

Edited by Ashley Primis

The big idea: Embrace total transparency

Lucinda Duncalfe

President and CEO, Monetate

Duncalfe has made a career of running successful businesses, so when the 53-year-old took the helm of Monetate two years ago, she knew she was going to insert her tried-and-true office culture m.o.: telling her staff everything. “It works top-down, bottom-up and crosswise,” says Duncalfe. Monetate is booming — the company helps customers like Patagonia and Sur La Table customize websites, newsletters and mobile apps to individual users — and Duncalfe believes that employees who are informed make smarter on-the-fly decisions, collaborate more efficiently, and are empowered to think and not just do. Information like industry context, financial reports and board meeting topics are shared on the regular. “The best people really want to work in that kind of environment,” Duncalfe says.

The big idea: Cut the costs on technology

Danny Cabrera

CEO and co-founder, BioBots

Biofabrication — the process of 3-D-printing human tissue — has been a game changer for researchers and pharma companies since the field exploded a decade ago. The only problem? The price tag. Printers could easily cost more than $100K. That is, until Cabrera, 24, and his partner, Ricardo Solorzano, 27, created the first desktop 3-D bioprinter in their dorm room at Penn. The Biobot 1 is a 19-pound, 12-inch cube that uses bio-ink, a combination of cells and biomaterials, to print out human tissue that scientists can use to develop and test new drugs, cure diseases, and eventually eliminate the organ waiting list. Labs from more than 20 countries have gotten their hands on one. Best part: Biobot 1 only costs $10,000, which is bargain-basement in the biotech world.

The big idea: Infuse a forward-facing company with a new back-end culture

Photography by Gene Smirnov

Scott O’Neil

CEO, Philadelphia 76ers

Forget, for a minute, the on-court futility of the past few years. If you peek into the back office, you can see this is definitely not the same old Sixers. O’Neil was hired in 2013 to run the Philadelphia 76ers and New Jersey Devils. Since then, the CEO has positioned his harried hoops franchise at the forefront of cool. O’Neil played a pivotal role in developing the team’s new state-of-the-art practice facility in Camden, and made room there for an in-house start-up innovation lab. Earlier this year, the team also became the first in the NBA to land a uniform sponsorship deal — with StubHub, for $15 million — and it’s the first pro team in North America to dive into the digital world of eSports. (Confused about eSports? It’s that video game tournament thingy your kids have been begging to go to.) But O’Neil’s impact goes beyond corporate deals. He’s instilled a Valley-esque vibe in the organization, plays pickup games with the sales staff, and offers 76 hours of paid time annually for each employee to devote to community service. “I come from a family of entrepreneurs, so I’m always thinking about opportunities to chase,” says O’Neil, 46. “This is the first time I’ve worked in an environment with a board that fosters that and encourages it. I’m like a kid in a candy store.”

The big idea: Make the Tupperware party work for high fashion

Photography by Gene Smirnov

Bela Shehu

Founder and designer, NINObrand

While this 37-year-old Albanian-born fashion designer sells her avant-garde women’s-wear collection through traditional means (via a whitewashed Rittenhouse showroom), it’s her other sales tactic that’s shaking up the retail scene. Shehu has assembled a team of stylish, well-connected women — dubbed Private Stylists — to peddle her clothes by hosting posh parties and trunk shows, exposing Shehu’s collections to in-the-know shoppers across the country. The vetting process is comprehensive, but the approach is working: Shehu has nabbed Private Stylists like local society queen Beka Rendell, whose deep Rolodex translates into well-attended shows and solid sales. (Shehu is in the process of training stylists in Birmingham, Atlanta, Miami and L.A., too.) The model eliminates the overhead of brick-and-mortar and an army of full-time employees, and turns shopping — which has become something of a solo sport — back into a social activity. “It seems to be the most effective way at the moment for the collectors to get that really personalized attention,” Shehu says. “The previously established methods don’t seem to work anymore.” Your only objective now? Get invited to Rendell’s next party.

The big idea: Take profits from savings

Marcelo Rouco

CEO, Ecosave

Retrofitting a high-rise to be energy-efficient can cost millions — a deterrent for most despite the long-term payoff. But Ecosave — a fast-growing Australian company that opened its first U.S. HQ in the area in 2013 — has an incentive for clients hesitant to take the plunge. The company performs a comprehensive audit (that can ring in at $50K) for free, and installs the equipment upgrades (better lighting systems, optimized cooling systems, smarter monitoring controls) with the promise that energy bills will be slashed by up to 50 percent. The clients save big, and Ecosave takes its profits from the money its clients save. (Comcast and GlaxoSmithKline have signed on.) They practice what they preach, too: Rouco, 47, says the energy bill at Ecosave’s 20,000-square-foot Navy Yard headquarters is just $800 a month — and that includes charging stations for three electric cars.

The big idea: Condos are for suckers

Lindsey Scannapieco, 30

Developer, Scout Ltd.

How’d you get the idea to revitalize Bok Technical High School? Twenty schools were up for public auction, and Bok was on there. My thought was that the neighborhood needed affordable spaces in which to work, build and make.

How have you attracted such eclectic tenants? You have a boxing gym, a preschool, a record shop, a bar and more. We haven’t done any marketing, so it’s really just been word of mouth. Today we have 52 different tenants. We didn’t want Bok to be just artists or just makers or just businesses. The idea was that it could be all of those things.

You’re a well-off white woman who renovated a former school in a working-class immigrant neighborhood. What did you do to involve residents? The building doesn’t lend itself to transparency, so we’ve done little things like create a newspaper. The second issue mapped all the community resources outside of the building. We’re hosting a block party. And we’ve worked closely with Southwark, which we think is a really exciting and phenomenal school.

In Philly, projects like Bok are relatively rare. Why? The school district sold Bok pretty affordably. If you buy a building at a really high price, the market is going to push you to take a very standard approach to development. I imagine we were quite a risk compared to the other bids for the project, which were probably standard conversions to residential. I think allowing and supporting people who take more risk will help. And honestly, that won’t always work. But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

The big idea: Make fast go faster

Photography by Gene Smirnov

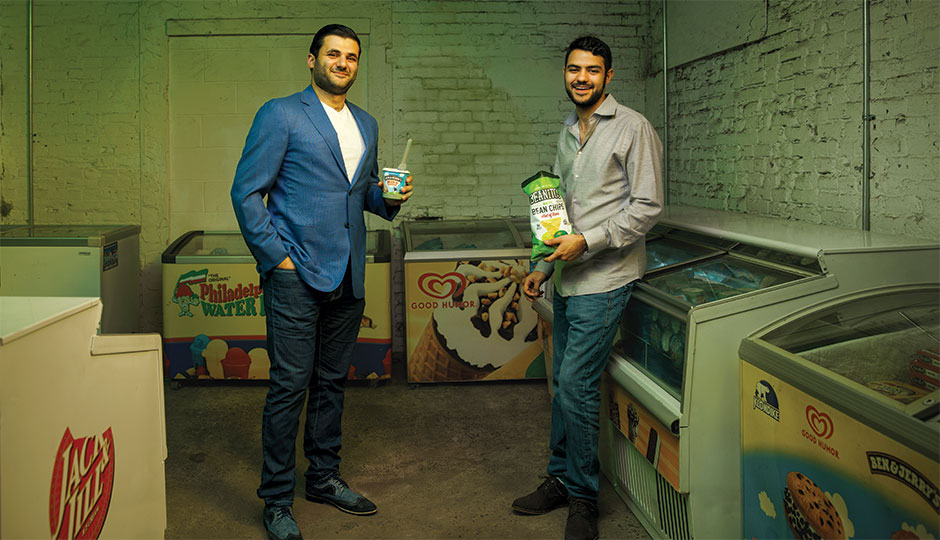

Rafael Ilishayev and Yakir Gola

Co-founders, GoPuff

Ilishayev and Gola, both 23, launched GoPuff in 2013, when they were juniors at Drexel. You can probably guess the original target demo from the company’s name, but now everyone’s a potential customer. The on-demand, app-based delivery service gets convenience-store items (snacks, beer, household goods) to your door in under 30 minutes, 24 hours a day, for a sub-$2 delivery free. GoPuff is now live in 12 major U.S. markets. “We believe that convenience stores aren’t convenient enough anymore,” says Ilishayev. Which is why they’ve built technology to carve their delivery time down to 15 minutes in 2017. “When you order an Uber, you expect it to be there in seven to eight minutes. There’s no reason delivery can’t be the same way,” says Ilishayev. And they’ve secured more than $8 million in funding to prove it.

The big idea: Be a resource first, a store second

Anthony Bucci, 36

Co-founder and CEO, RevZilla

Bucci has leveraged social media — his YouTube channel has more than 270,000 subscribers — to create a multimillion-dollar motorcycle e-commerce store. Here’s how: “We have all these different types of content, and they all play into this big strategy of giving away something for free. When you take the expertise, the tech, and the media we build, we actually transcend retail and become a resource. And if you can be the trusted resource for any tribe, they become part of your cause and support you.”

The big idea: Redefine your ideal employee

Gabriel Mandujano

Founder and CEO, Wash Cycle Laundry

Six years ago, Mandujano, 34, a socially aware entrepreneur whose educational credits include Wharton and Cambridge, decided to test whether a pedal-powered urban laundry service was feasible. Wash Cycle’s tricycles soon became a familiar sight in Philly, and the concept was expanded to D.C. as well — proving that three wheels are a viable alternative to trucks on narrow city streets. What isn’t obvious: More than half of Wash Cycle’s workforce is made up of people who used to be homeless, in jail and/or welfare-dependent. And the company’s employee-retention rate is a startling 80 percent, compared to a norm of 45, thanks to a network of support and vigilance. According to Mandujano, “I don’t think anyone here would be in the laundry business if it weren’t for the impact we’re creating.” With the company’s high-efficiency washing machines, Wash Cycle is a “triple-bottom-line” enterprise, improving traffic, the environment and human lives.

The big idea: Start a for-profit to fund your nonprofit

Photography by Gene Smirnov

Sylvester Mobley

Executive Director, Coded by Kids

In 2014, Mobley, a 37-year-old Iraq war veteran and tech developer, started offering coding classes at a South Philly rec center — first to a handful of kids, then, eventually, to hundreds. Scaling up required some ingenuity, given the paucity of grant money in the local nonprofit sector. So Mobley found another path: establishing Coded by U, a for-profit business managed by the same team as his nonprofit. Now, on any given day, Mobley is running a business that earns contracts from schools and companies — for teaching students or workforce

development — or he’s offering free courses and entrepreneurial mentorship to kids at rec centers. The hybrid works because there’s so much overlap of curriculum and mission; it’s just a matter of getting the financial structures squared legally. “If someone approaches us and says, ‘Hey, we want to give you money’ and there aren’t a lot of strings attached, we’ll take it,” Mobley says. “Other than that, we’re going to sustain ourselves through our business.”

The big idea: Create a culture of empathy

John J. “Jack” Lynch III, 56

President and CEO, Main Line Health

In the federal government’s new hospital star quality ratings, your Paoli Hospital was one of just four hospitals in the state to earn a five-star rating. Your Lankenau, Bryn Mawr and Riddle hospitals all got four-star ratings. How did you beat the big-city guys? We take good care of our staff, so they’ll feel compelled to take great care of our patients. Lots of hospitals do a really good job. To take it to the five-star level, you’ve got to treat patients like family members.

What do you prioritize? Our number one priority is to identify and ameliorate the disparity of care. Research shows that medical care varies for people who look different, who talk differently, who have different lifestyles. It’s caused by unconscious bias. We’ve implemented a two-day cultural sensitivity seminar that trains staff on diversity, respect and inclusion. Every one of our 11,000 employees participates. It costs us millions. But we get an exponential return in terms of understanding other cultures, racial differences, sexual orientations.

How else have you addressed disparities of care? We have a program at Lankenau that pairs medical students with patients who may have barriers to access, trying to identify what they need help with, whether it’s buying healthy food or finding a babysitter or a ride to the hospital. There are two unbelievable outcomes. First, you get better compliance when patients get access. The other, unintended benefit is that it makes the students better doctors. Many of them come from privileged environments. They aren’t aware of the risks and challenges patients face in their daily lives.

Main Line Health appears regularly on “Best Places to Work” lists. How do you keep employee satisfaction high? We try to model the behavior we’re looking for. And we have an amazing tool called eFeedback. Anybody on staff can send a message, and it goes to HR and to my office. I get every single one of them, in real time. And we have a site where everyone can read our responses. We don’t take those high star ratings for granted. You can’t achieve recognition and you’re done. I know there’s a disgruntled employee out there. It’s our job to find that employee.

The big idea: Go low-tech

Megan Heere and Jennifer Rodriguez

Co-founders, the Sleep Awareness Family Education Program, Temple University Hospital

About two years ago, Heere, a 34-year-old pediatrician, and Rodriguez, a 42-year-old nurse, got their hands on some alarming data: The city’s rate of sudden infant death syndrome was high in comparison to the rest of the country. Their research spotlighted the problem: Mothers leaving Philly hospitals were more likely to bed-share — a risky behavior associated with infant mortality — if they didn’t have a separate space, like a bassinet or a crib, in which their infants could sleep.

Inspired by a Finnish tradition of giving new mothers so-called “baby boxes,” the pair rolled out a similar program here in May. Temple’s baby boxes — yes, they truly are cardboard boxes — are secure and portable places where babies can safely snooze away. The boxes are presented alongside in-hospital education and are filled with all sorts of items new parents need, from booties to baby wash. After giving out 1,000 of the 3,000 baby boxes they have funding for, Heere and Rodriguez can’t yet say whether the program is impacting Philadelphia’s SIDS rate. But they do know, simply from hearing back from new mothers, that patient satisfaction is high. As Heere says, the program seems to say to new parents, “Temple cares about us.”

The big idea: Keep nonprofits afloat

Photography by Gene Smirnov

Nadya K. Shmavonian, 56

Director, Nonprofit Repositioning Fund

What’s the goal of the Repositioning Fund? Leaders and boards of nonprofits should be talking about succession planning; they should be having conversations about mergers and acquisitions, or other ways to make each other stronger by joining forces. In the for-profit sector, these thoughts are a normal part of doing business; you’re always looking at your potential aligned partners and your competitors with an eye toward whether there’s a way to unite. The overarching objective of this fund is normalizing the conversation in nonprofits.

Why the urgency to work on this now? The whole compact between funders and nonprofits is very different than it used to be. There’s been a proliferation of nonprofits and not enough funding to go around. Something isn’t right, and I don’t see it ever going back to the way it was in the good old days.

What role do you play in facilitating these collaborations, mergers and shared resources? I am most definitely not a yenta. I don’t do matchmaking. If somebody comes to me and they have a partner in mind, then we begin the discussions formally. If you’re a nonprofit and you may be making a decision to merge or go under, there’s the dynamic of how and when you go talk to your funder about that. I am Geneva. I am a safe space where people can share what they’re struggling with.

The big idea: Don’t ignore the niche market

Tom Wlodkowski

Vice president for accessibility, Comcast Cable

Tom Wlodkowski, 48, was born blind. So he knows the visually impaired would consume TV as voraciously as the sighted if they could. “I was missing out on so much TV,” he laughs. “I figured I’d finally landed in a place where I could do something about that.” Since arriving at Comcast in 2012 after 10 years running AOL’s accessibility program, he’s spearheaded technologies that improve content discovery for the millions of Americans with disabilities. His team’s “Talking Guide,” a feature available on the X1 platform, reads program information aloud and makes the DVR accessible to the visually impaired. These features wound up changing how program data is organized and presented across the system, for the better. There is, of course, a huge opportunity in accessibility solutions: Wlodkowski says one third of U.S. households include a person with a disability, and that represents some $200 billion in discretionary spending. Wlodkowski feels Comcast’s accessibility efforts, along with the voice-controlled remote (think Siri, but for your TV), are steps toward an even loftier goal: “By thinking about these edge cases,” he says, “we actually end up building a product that works better for everyone.”

The big idea: You should be able to “Yelp” anything

Ofo Ezeugwu, 24

CEO and co-founder, WhoseYourLandlord

Ezeugwu’s site lets tenants review landlords. Here’s why it could change the rental industry: “We’ve grown up with Yelp, Facebook, Ask.com — it’s such a transparent environment. We want to feel like we’re getting the truth delivered to us all the time. Real estate is such an antiquated industry, and the level of power has always tilted one way. If we can show who the good renters and landlords are, that will strengthen the rental community as a whole.”

The big idea: Throw more than money at start-ups

Photography by Gene Smirnov

Rudy Karsan

Founder, Karlani Capital

Karsan is a member of a small club in Philly — he sold Kenexa, a software company he co-founded, to IBM for more than a billion dollars in 2012. He’s passionate about Philly’s start-up scene but wanted to do more than take management fees from just-born companies. So Karsan, 59, acts more like a loving big bro, and through Karlani Capital deploys a team of experts — people in marketing, finance, operations, employee assessment, sales — to guide the start-ups. In return, the companies don’t pay for the services until revenue starts coming in, when they have the choice of paying Karlani back in equity or cash. “People are really looking for three things over and above money,” says Karsan. “They’re looking for strategic help, operating help and customers. We force them to make decisions.”

The big idea: Give regular Joes access to big wealth

Michael Forman

CEO, FS Investments

Wall Street isn’t made for the little guy. Vast stretches of the financial industry are cordoned off to individuals, while wealthy institutions and pension funds have exclusive access to cutting-edge opportunities. The Great Recession further exacerbated this. “Mainstream investors had virtually no way to invest outside traditional stocks and bonds,” says Forman, 55. FS responded by basically inventing a new investment vehicle: the non-traded business development company. It’s like a private equity fund, except you can get in for $5,000 rather than millions. “We often refer to this as the democratization of investing,” says Forman, who’s caught the attention of big players like Goldman. The recipe has been wildly successful: FS Investments, located in the Navy Yard, has grown from managing $110 million to $18 billion in under a decade.

The big idea: Start a grassroots marketing movement (that’s authentic)

Justin Rosenberg

Founder and CEO, Honeygrow

When Rosenberg, 34, opened his first Rittenhouse quick-serve eatery in 2012 — he now has nearly a dozen locations in four states — he wanted it to encapsulate a lifestyle. “It’s this idea of real food from trustworthy sources and tying that back to a healthy way of living,” he says. Now, that idea has a name: hgAthletics, the newly minted umbrella for the company’s popular community-focused fitness events. Rosenberg’s recipe is simple: Start with a company culture that encourages health and work-life balance, and those values will seep into your products. It helps to hire a yoga instructor as your brand director. Says Rosenberg, “When you come to one of our events and have a good time, it’s really us the person buys into.” If you stick around for a salad, that’s even better.

The big idea: Believe everyone can win

Haile Johnston and Tatiana Garcia Granados

Co-founders, Common Market

Wharton grads Haile Johnston, 43, and Tatiana Garcia Granados, 41, saw how people in their neighborhood wanted fresh, high-quality food but had to leave Strawberry Mansion to get it. Wholesale food distributors largely ignore low-income neighborhoods despite the demand. So Johnston and Granados started their own distribution system: a nonprofit that connects local farms — also ignored by the big guys — to local institutions like hospitals, schools and grocers. Now, they service the entire mid-Atlantic region, with programs rolling out in Atlanta and New York soon.

The big idea: Outsource the annoying parts of being an artist

Thaddeus Squire

Founder and managing director, CultureWorks Greater Philadelphia

Over a third of arts and culture nonprofits in Philly operate with structural deficits, but Squire’s “management commons” lets groups pool resources to make the most of the money they have. How it works: Nonprofits and for-profit entities buy into the commons (typically handing over 12 percent of revenue) in exchange for management help, whether that’s locating revenue streams or streamlining bookkeeping. “It’s not about training wheels,” says Squire, 43. “We make a very polemical case against ever operating your own nonprofit.” It’s a model that works: CultureWorks hopes to launch its Houston branch in 2017.

The big idea: Refresh an old concept

Tom Wingert

Marketing director, City Fitness

Considering the recent surge in boutique fitness studios and grassroots fitness communities like the November Project, big-box gyms, arguably the grandpas of the fitness world, are struggling to seem cool. And yet City Fitness — a local big-box gym that’s growing — has positioned itself as the cool kid using the same community-engagement techniques the newer places use. In the past year, City Fitness, with 29-year-old Wingert at the helm, mounted its first free citywide challenge, MyCityMoves (the Eagles’ Connor Barwin participated), driven by social media, then added gratis open-to-the-public pop-up events. Wingert also lured grassroots fitness powerhouse Jon Lyons of Run215 to his marketing team. “Gyms are community institutions, but they aren’t normally perceived that way, and they don’t usually think of themselves that way,” Wingert says. Until now.

The big idea: Show artists how not to be starving artists

Andrew Simonet

Executive director, Artists U

This 47-year-old West Philly dad has been creating art in Philadelphia since 1993, when he co-founded Headlong Dance Theater. Through the years, he noticed a disturbing trend: brilliant artists struggling to survive. So he started Artists U in 2006 to help artists review finances, prepare taxes, and come up with strategic plans for their lives that incorporate the work they want to do. The U has even offered seminars — like “Artists Raising Kids” — that thousands have attended. “It’s amazing,” laughs Simonet. “Everyone does strategic planning. Everyone but artists.” With a growing endowment, he’s expanded to Baltimore and South Carolina and published an e-book that’s been downloaded close to 80,000 times.

The big idea: Rebrand the Philadelphia Lawyer

Neil Cooper

Executive partner, Royer Cooper Cohen Braunfeld LLC

It seems as though there’s dour news all over the legal world these days — troves of unemployed law-school grads, an assault on the billable-hour model, endless contraction. And then there are stories like RCCB. In three short years, this boutique firm with offices in Conshohocken and Center City has tripled in size. Differentiation is more important than ever, and Cooper has built an authentically charismatic brand for the firm. “In this day and age, clients and recruits want to know what makes you tick,” says Cooper, 47. What’s so different? Lawyers who prioritize cost efficiency and who’ve worked for entrepreneurs and can speak to business strategy.

The big idea: Find money to support journalism

David Boardman, 59

Dean, School of Media and Communications, Temple University

You’re a board member of the Institute for Journalism and New Media — the nonprofit that now owns the Inquirer, the Daily News and Philly.com. Are there other models of nonprofit journalism that you’re looking to for inspiration? Really, the rest of the country is looking to us. Philadelphia has suddenly become the most interesting center of journalism in the country. The creation of this institute and the potential it has to build a bigger endowment and spin off grant money, not just to Philly.com but to other local media as well, is really exciting.

Will the Inquirer and Daily News exist in print form five years from now? The economic model is changing so dramatically, and I don’t see how a seven-days-a-week printed newspaper delivered to people’s doorstep makes a lot of financial sense. And two of them particularly doesn’t make any sense. I am an advocate for metropolitan newspapers moving toward a model of putting out one really superb weekend newspaper and then top-quality digital and mobile products during the week.

The big idea: Make resale upscale

Danny Govberg

President and CEO, Govberg Jewelers

Watches, like so many other big-ticket consumer goods, have a value that lives on well past the original owner. But up to this point, finding a second home for your timepiece — and figuring out how much it’s actually worth — has been a challenge. Enter Govberg OnTime, a free app that uses algorithms to give owners an estimated value of their watches and connects watch collectors with Govberg’s horological experts. It’s the brainchild of Danny Govberg, 56, who launched the app last year as a way to make his 100-year-old family biz a global force in the luxury-watch industry.

The big idea: Modernize an old-school industry

Christopher Franklin, 51

CEO, Aqua America

When you became CEO, what did you think needed to change? I wanted a management team that was broad-based, that looked more like our customer base. We were a bunch of white guys, and frankly, we needed to diversify the table. My first five or six hires in the senior leadership team were all women, and from diverse backgrounds.

Why is that important? When you’re problem-solving or creating strategy, if you only have a limited set of points of view, you really miss opportunities.

Is there something about the water utility business that means a lot of these companies have old-fashioned work cultures? When you look at our office space, it tends to be walls and old plans. We’re trying to bring a much more collaborative approach. We’re building little coffee bars. Nothing that you’d walk in and say “Wow,” because we’re a public utility and we’re very conscious of our customer rates. But we’re trying to bring innovation and collaboration.

Why is it important to have collaboration like that? In any business, silos tend to develop. People get ingrained, and there are communication walls that are informally built. The more you can innovate, the more you can fast-track projects.

The big idea: Create your own talent

Earnie Stewart

Sporting director, the Philadelphia Union

The Union recently lured U.S. Soccer Hall of Famer Stewart away from soccer clubs in the Netherlands because the owners needed someone with long-term vision. The team has a healthy fan base, but it’s often sported one of the league’s less impressive payrolls. So Stewart, 47, decided to double down on developing homegrown talent through the Union’s minor-league affiliate, the Bethlehem Steel; pushing its youth academy, which reaches kids as young as seven; and turning to analytics to help unearth hidden gems. “My first question for the ownership group was, ‘What are our core values?’” he says. “We had to create a vision of what we believe soccer should be in Philadelphia.”

The big idea: Let customers come to you

Lauren Boggi

Founder, Lithe Method and Lauren Boggi Active

“The workout world is so strange right now,” says Boggi, the 38-year-old founder of Philly-based Lithe Method workout studios. “There’s so much free content. You really don’t have to be in a studio or a gym.” Translation: You don’t have to open a billion locations to make money. Last summer, Boggi launched LB Active, a digital workout program that anyone with a screen can pay to access. With smart marketing (free Instagram challenges), she’s positioned herself as a Jillian Michaels-style brand — one that now has a global reach. (She figures that some 70 percent of her virtual devotees aren’t local.)

The big idea: Grow responsibly

John Fry

President, Drexel University

When our universities grow, Philly wins: more jobs, more buildings, more students who could morph into more city dwellers. But in a dense urban environment, growth often means displacement. “It was very clear to me that these institutions — Penn, which had grown west into neighborhoods, and Drexel, which had grown north into neighborhoods — weren’t going to be able to do that anymore,” Fry, 56, says. “We had to figure out other ways to grow.” For Drexel, that meant east, toward parking lots, unused rail yards, and one of the busiest rail stations on the East Coast. What Fry sees: massive potential in the form of the Schuylkill Yards, a 20-year, $3.5 billion investment in new academic space, commercial buildings, public parks and business incubators that could “not only embellish what Drexel is doing … but also create something that would really bring great commercial potential,” says Fry.

The big idea: If you build it, you can sell it

Patrick Cunnane

CEO, Advanced Sports Enterprises

When Cunnane, CEO of the Philadelphia company behind Fuji and a number of other bike brands, learned that Performance Bicycle — a 106-store retail chain, and one of the largest distributors of his bikes — was for sale last November, he took a moment to think about … sunglasses. Specifically, Luxottica, the parent company of Ray Ban and Oakley that also owns Sunglass Hut, Pearle Vision and more. So this past summer, Cunnane, 58, got into the brick-and-mortar business, believing that buying the country’s largest bicycle retailer would give ASI control of its entire supply chain, better sales data, and the ability to push its brands more prominently. The acquisition also included two online properties, which makes for the ideal “omni-channel” buying experience many makers strive for: Customers can now get ASI bikes whenever, wherever and however they want.

The big idea: Make the avant-garde accessible

Nick Stuccio

Founder and president, FringeArts

Twenty years ago, the Philadelphia Fringe Festival was a tiny artistic endeavor geographically limited to Old City. These days, the fest — now known as FringeArts — extends into virtually all of Philly’s neighborhoods and presents the most innovative and daring live arts from Philly and around the world. Three years ago, the organization opened an ambitious theater, restaurant and beer garden at Delaware and Race, moving from three weeks of performances each September to a year-round brand name and a constant source of income. That this nonprofit is now a household name means the vision of Stuccio, 53, has impacted all the arts in Philadelphia.

The big idea: Expand your target demo

Jim Kenney

Mayor of Philadelphia

A few years ago, local education advocates presented Mayor Kenney with an innovative policy idea: Schools can be more than just places for eduction. “Other cities were successfully addressing the non-academic barriers that keep our kids from achieving in the classroom,” says Kenney, 58. So after winning a very public battle for funding (hello, soda tax), his administration opened the first nine “community schools” this fall, where collaboration between agencies like the Office of Education and the public health department are increasing health services and nutrition programs. “The community-schools designation means a great deal to the students, teachers, parents, community members and principals,” says the Mayor, “because it demonstrates that the city is going to support them as much as we can.”

The big idea: There’s another way to get a business education

Tayyib Smith and Meegan Denenberg

Founders, Institute of Hip-Hop Entrepreneurship

The Institute of Hip-Hop Entrepreneurship isn’t out to discover the next big pop star; it’s out to flip the script for entrepreneurial opportunity, informed by the myriad ways hip-hop impacts modern business and culture, from graphic arts and fashion to guerrilla marketing, and the fact that a lot of brilliant minds never make it into the traditional business-school pipeline. “If you live at 60th Street and you’ve got a good idea, it’s like walking across the Sahara Desert to get to Wharton,” says Smith. The IHHE’s free nine-month program features regular lecturers and high-profile guests; its first 24 participants were chosen, explains Denenberg, because they’ve got “the type of hustle, ambition and thought process to work well within the institute.”

The big idea: Growth is good

Kirtrina Baxter

Community Organizer, Soil Generation and Garden Justice Legal Initiative

Baxter, 46, helps Philadelphians get or keep legal access to otherwise “vacant” or undeveloped land in their communities that they’ve improved — or hope to improve — through gardening and farming. (GJLI’s Grounded in Philly website offers a slick tool for tracking the city’s 40,000-plus lots that have no known use.) Through her work in Soil Generation, Baxter has galvanized the city’s burgeoning urban agriculture community into a policy force to be reckoned with. At a September City Council hearing on farming in the city, a Pennsylvania Agriculture Department rep called Philly’s gardening and farming community a “national model,” and Council members marveled at the number, passion and diversity of advocates who turned out to show their support. “We all eat, so the connection is pretty simple,” says Baxter. “Food affects everyone, so everyone’s here at the table.”

The big idea: Mobilize a community

Luis Cortés Jr.

President and CEO, Esperanza Academy Charter School

Here’s a dirty little secret about Philly’s charter schools: Many of the crown jewels you hear about have fewer poor, disabled and minority students than typical public schools. Hunting Park’s Esperanza Academy Charter High School is different: Ninety percent of the kids in the predominantly Latino school are economically disadvantaged. And yet the charter’s graduation rate is more than 90 percent, and its college attendance rate is 65 percent. Esperanza isn’t perfect — its middle school hasn’t proven as successful as its high school — but part of its secret sauce is that it was a community school before community schools were cool: Esperanza is a $35 million, 350-person mega-nonprofit that provides everything from job training to immigration legal services to renovation of homes in Hunting Park. That’s largely thanks to the vision of 58-year-old Cortés, who says his work is inspired by the biblical teaching to help “the least of these.” If more of us thought that way, Philadelphia would be a much more equitable place.

The big idea: Use design to solve health-care problems

David Asch

Executive director, Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation

In 2012, Penn asked Asch, an M.D., an MBA and a professor, to refocus the Innovation Center toward delivering services — helping patients get what they need while making it easy for staff to do their jobs. Being exposed to colleagues from different fields taught Asch what Steve Jobs discovered decades ago: What we see, hear and sense markedly affects how we feel. Which is why he hired a team of multidisciplinary designers to solve the most sensitive of problems, like creating an easy-to-use website that makes filling out end-of-life directives less stressful. “Historically, hospitals have looked at patient surveys like report cards,” says Asch, 57. He now believes that medical systems can’t succeed without practices that incorporate our feelings into the equation.

The big idea: Make grants more sustainable

Paula Marincola

Executive Director, Pew Center for Arts & Heritage

The age of on-demand everything has brought fresh challenges for static cultural and arts organizations; people want audience engagement, pop-ups, iPhone apps. Pew’s “advancement grants” reflect this new landscape. These investments are meant to be longer-term and more open-ended, so nonprofits can figure out how to stay ahead of the curve. Since 2014, Pew has awarded $5.7 million in advancement grants to catalyze change in high-performing organizations, including money for the Franklin Institute’s brand-new digital media strategy (including virtual-reality technology) that will pay dividends for years to come. “These are about the very specific challenges that cultural organizations are facing in 2016,” says Marincola. “A particular response to a particular moment.”

Published as “Philly Rebooted” in the November 2016 issue of Philadelphia magazine.