This Philly-Area Expert’s Creative New Book Gets Real About Postpartum Depression

Through relatable comics and interactive activities, Karen Kleiman's Good Moms Have Scary Thoughts tries to help more depressed moms feel less alone.

Postpartum depression expert Karen Kleiman and illustrator Molly McIntyre’s new book tries to put a relatable face on postpartum anxiety and depression. / Illustration by Molly McIntyre

When you’re in the throes of trying to keep a tiny human alive, the world around you may seem a little gray. After all, you’re likely not sleeping very much. You’re probably dealing with residual pain from childbirth. And your attention is so focused on your baby that you’re definitely not taking the time to cook, shower, or grab coffee with friends on a regular basis.

All of these factors can combine to create what’s known as the “baby blues,” intense feelings of sadness or moodiness that, along with anxiety and bouts of crying, make you feel like you can’t function in what’s already an overwhelming environment. Fortunately, these sensations tend to fade after a few weeks. If they linger and become worse, though, we call them postpartum depression.

For a long time, these symptoms didn’t have a name. For longer, women have been afraid to share them with friends or doctors, believing these feelings made them unfit to be mothers or that child welfare services would take their children away as a result. The Inquirer recently ran a story about how this latter fear may still be justified, particularly for women of color. “We live in a culture that doesn’t make it easy for women to talk about not feeling good,” says Karen Kleiman, a longtime clinical social worker and the founder of the Postpartum Stress Center in Rosemont.

The good news is, the needle has started to move. In general, more people are talking about postpartum depression; follow #maternalmentalhealth on Twitter for a sample. The FDA even recently approved the first drug to specifically treat postpartum depression. (It’s $34,000 per treatment, though, so how many people it can actually help is questionable.)

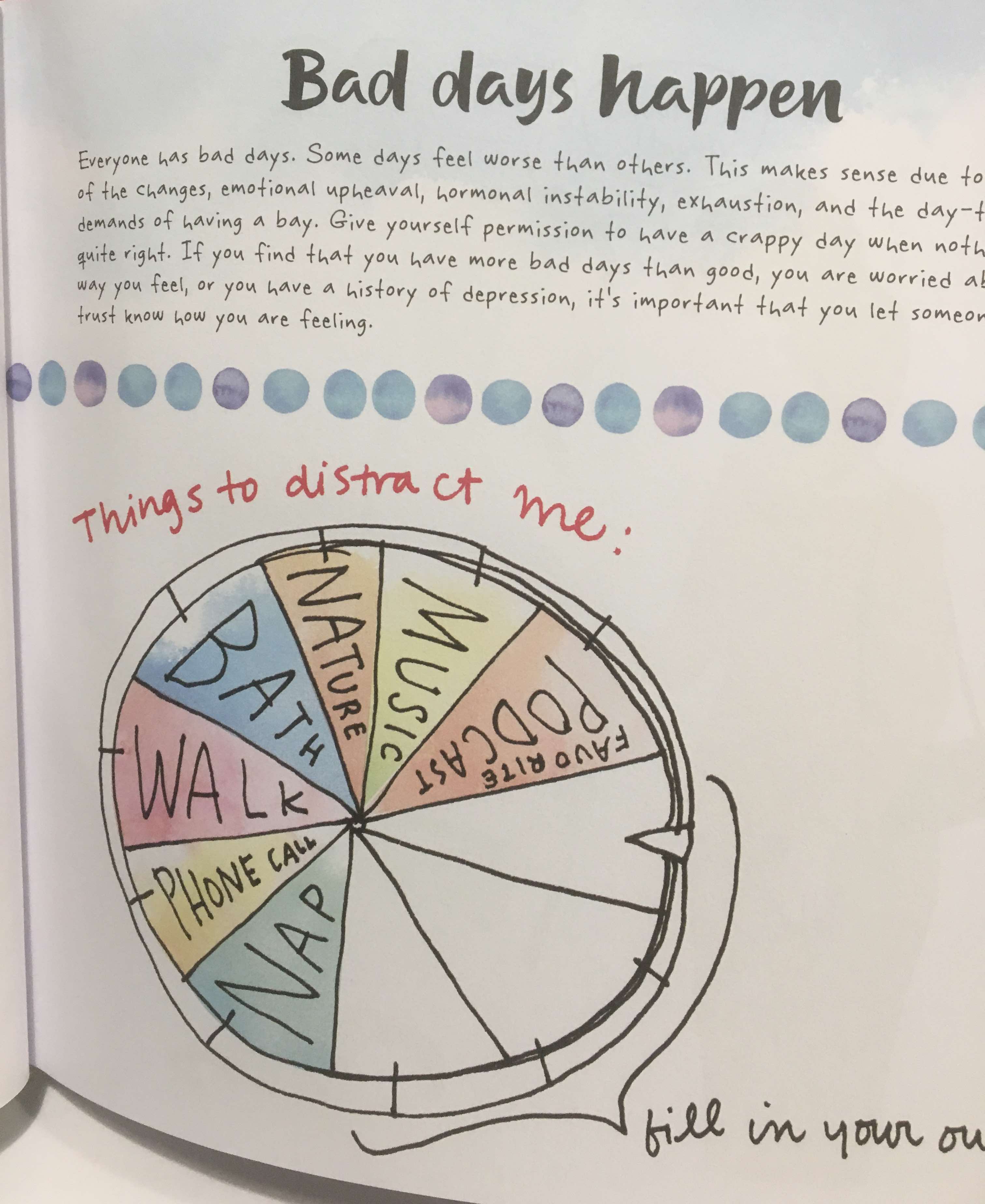

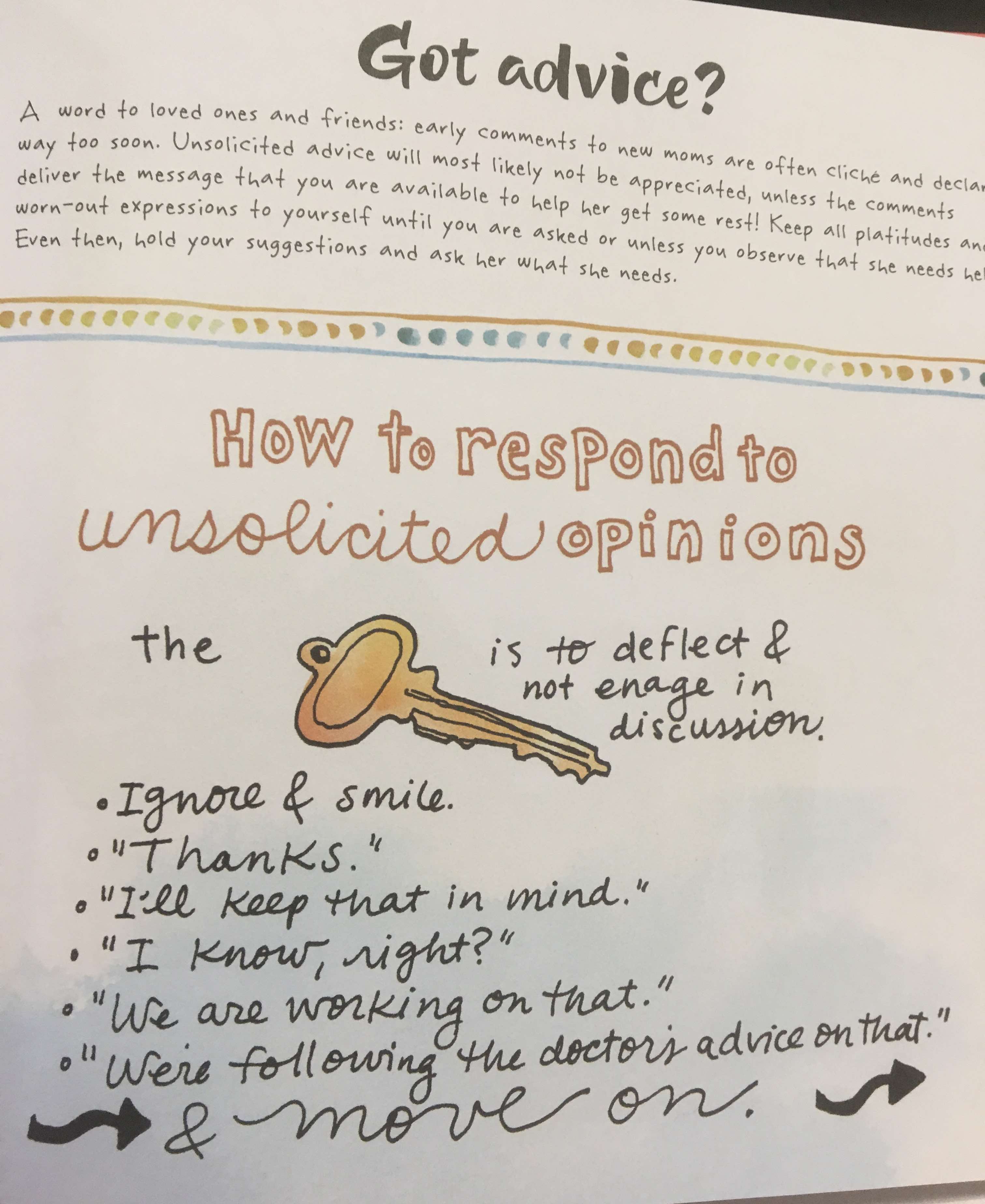

And locally, Kleiman, who’s been working in the postpartum depression world for more than 30 years, has come up with a creative way to reach more mothers: Good Moms Have Scary Thoughts: A Healing Guide to the Secret Fears of New Mothers, an interactive book with comics, drawn by illustrator Molly McIntyre, that add some lightness to the serious topic. It’s essentially a how-to guide for new moms trying to manage their stress and anxiety, complete with lists of suggestions such as, “How to respond to unsolicited opinions” and prompts like, “Make your own mantra.” It’s simultaneously hilarious, raw, and empowering.

In her new book, Kleiman provides prompts for new moms looking to manage their stress, anxiety, and depression. / Photograph by Mary Clare Fischer

In honor of World Maternal Mental Health Day — and in advance of her Q&A and book signing on May 17th at Shakespeare & Co. — we chatted with Kleiman to get a read on how the postpartum depression conversation has changed, why we need more educated doctors, and which of her book’s clever illustrations are her favorite.

BWP: What made you want to write Good Moms Have Scary Thoughts?

Kleiman: There was already a section on our website that talks about what are scary thoughts, how do we define them, what do we do about them. Then we started a #speakthesecret campaign on Instagram and created a forum on our website, so moms could anonymously insert this scary thought they were having. We’ve found that when moms talk about it, share it, get it into a safe space where they’re not going to be judged, their anxiety decreases. It was the kind of thing that could get really scary and messy, but instead it turned out to be wildly popular.

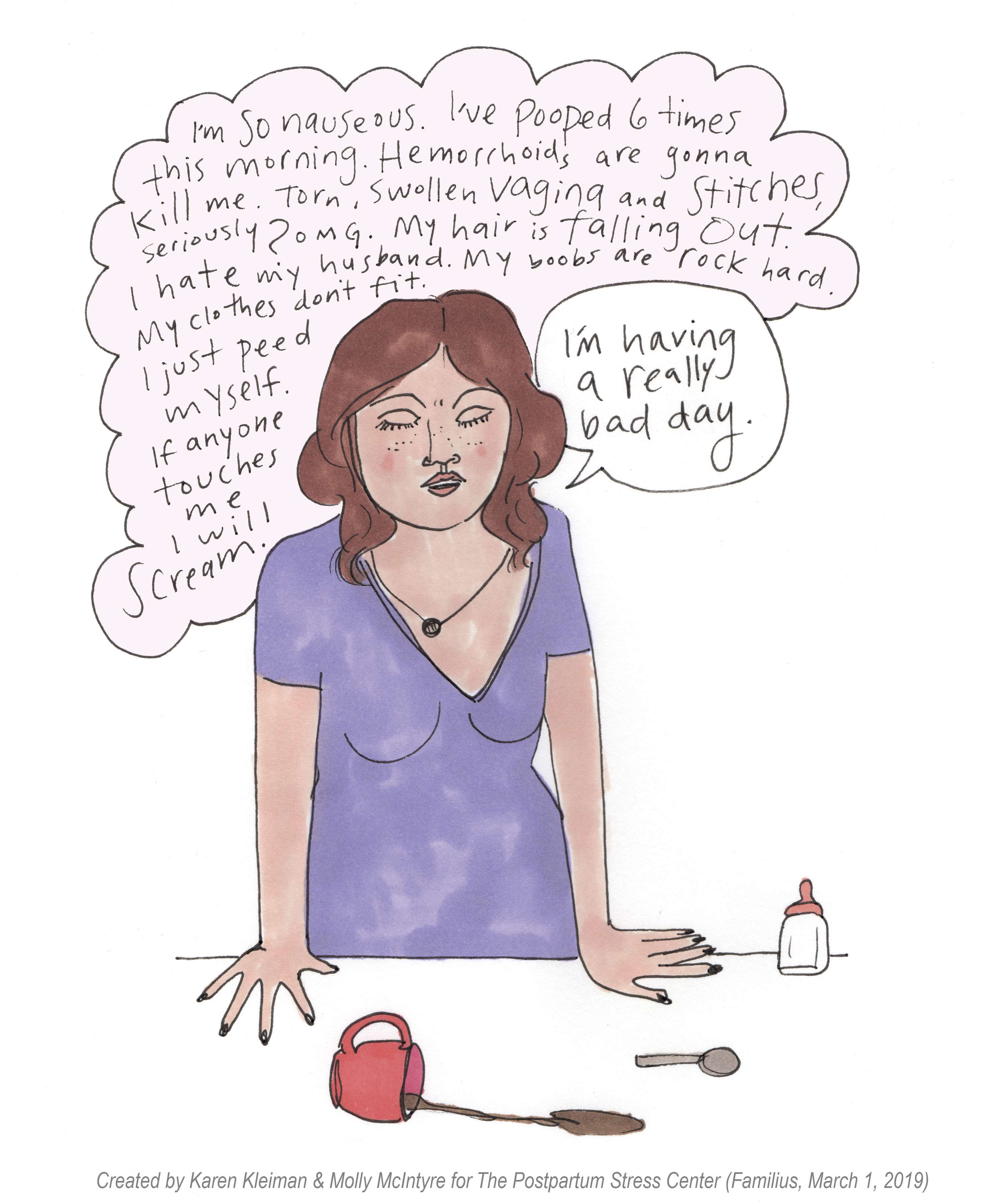

The first of Kleiman and McInty’re comics to go viral. / Illustration by Molly McIntyre

I found Molly [McIntyre’s illustration] work on another website. I forget where. It could have been Mutha Magazine. She’d done a piece on breastfeeding. I loved her style, which is so raw and real. She can express so much with her faces. I basically called her, and I said, ‘Let’s make a comic out of some of these thoughts.’ (They weren’t specifically the thoughts the moms had said.) The first one went viral. It’s where a partner says, ‘Do you need anything?’ and she says, ‘Nope.’ Then she has the full list of, ‘I could use this, this, this.’ It’s been translated into tons of international languages. Every single mom relates to the idea of ‘I need so much, I can’t even tell you what I need.’ We started compiling these comics and putting them out on the internet and got such a rave response that we started looking for a publisher.

How did you come up with the different things the moms said?

They literally come pouring out of my brain. I don’t know a nicer way to say it. I’ve been doing this so long, and I’ve heard so many of, not the same words necessarily, but the same themes. It was the same thing when, in 1986, I decided to write This Isn’t What I Expected: Overcoming Postpartum Depression. I remember saying, ‘I’m hearing the same thing over and over and over again. I need to put this down on paper.’ I honestly didn’t know anything about postpartum depression until my patients started telling me what they needed. There’s nothing really in books that can teach you what it feels like to give birth to a child and feel that this is an epic fail and that you can’t manage it and you made a mistake and, ‘How do I go back to my life before?’ and paralyzing anxiety and fear and rage. Moms have always and continue to teach me what I need to know, so I can help them feel better.

What postpartum life can be like, in a thought bubble. / Illustration by Molly McIntyre

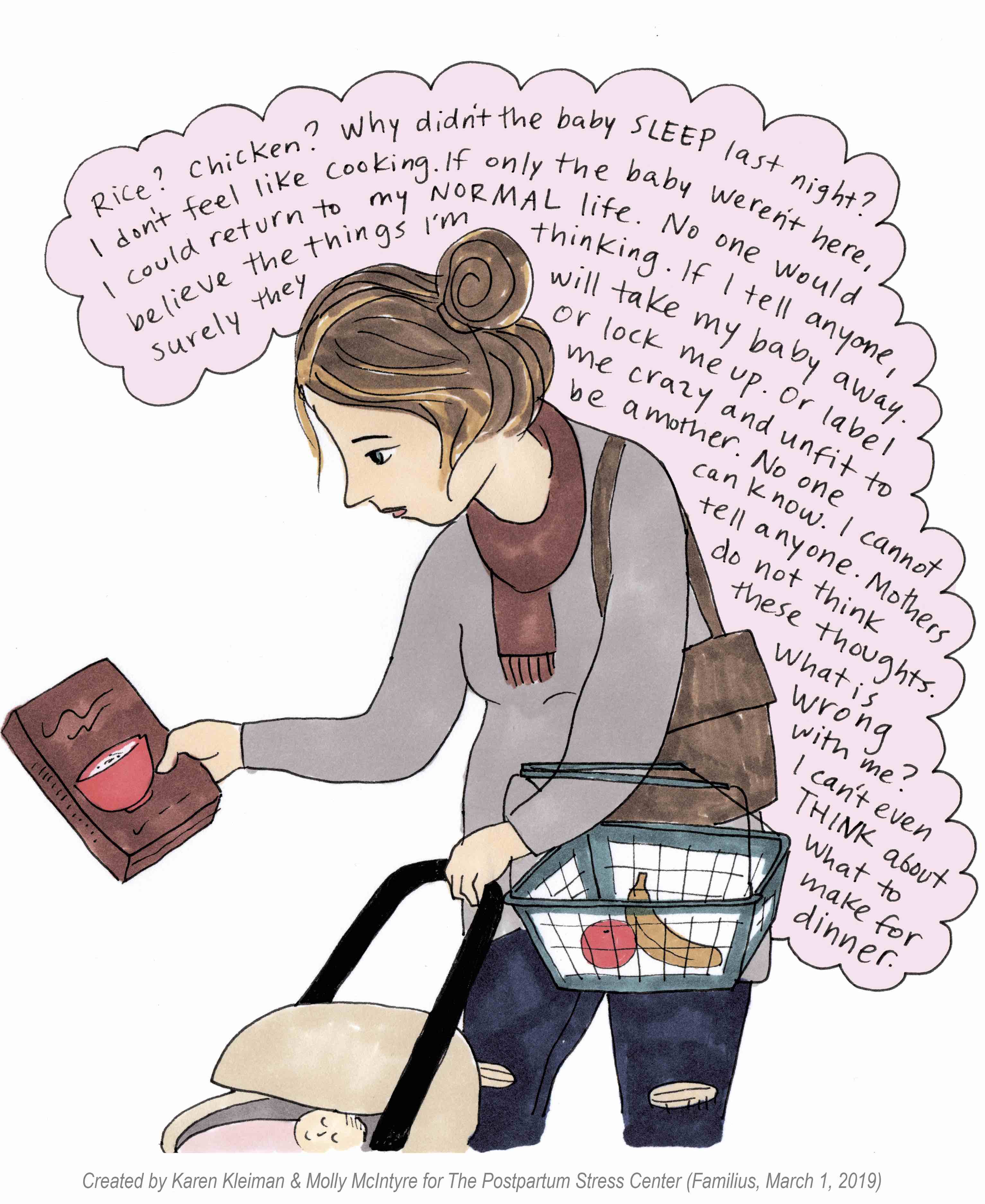

Is there one of the comics that you think particularly illustrates that?

I love the one with the chicken and the rice. That was based off my own experience where I was walking up and down the aisles going, ‘Fuck.’ I didn’t have my baby with me so that felt great, and I wasn’t particularly depressed and anxious, and I still just couldn’t think. And I love the one that went viral. And I love that some of them are sort of like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s funny haha,’ but most of them are pretty serious and some of them are extremely serious. I love that in the same sweet little book, we can talk about [worrying about] throwing the baby on the concrete, wanting to kill yourself, and walking into a room with strangers and not knowing what anyone’s talking about. I was worried about the psychosis one. But it feels remarkably liberating that we are now allowed to put those symptoms out there.

When simple decisions seem difficult to make. / Illustration by Molly McIntyre

Do you think postpartum depression is becoming more common?

It’s been present and in the dark shadows for a very long time. In fact, one of the stories I tell a lot when I’m speaking is: When I first started studying this back in the late ’80s, I put a $35 ad in the Main Line Times that I was a therapist studying postpartum depression, and if you’ve recently had a baby, please contact me for an interview. I got three phone calls. Two of the three women who came to see me individually were over 70 years old. They sat with me saying this was the first time they were talking about how bad they felt. They didn’t tell their partners, their mothers, their neighbors. That was the day I knew I had to do something.

So, yes, it’s been around for a long time, and we haven’t talked about it. Now that we’re talking about it, things are getting a little conflated. We’re running into blurry diagnostic lines, where women are diagnosing themselves, throwing around labels, calling everything postpartum. On the one hand, we want to advocate for this and validate it. On the other hand, everybody and their sister doesn’t have postpartum depression. (It does appear on a continuum; there are women with clinical depression who aren’t as severe when it comes to functionality, but they still go to bed thinking they’ve made a mistake.) It can become complicated, and we want to make sure we’re taking care of the women who are severely sick.

Is there a reason why we’re starting to talk about postpartum depression more? Or many?

I think there’s so many reasons I don’t even know how to answer that. I think it’s the intersection between women’s rights and #MeToo and transparency and fluidity of gender roles and awareness and advocacy and legislative attention. Thirty years ago, I was just a therapist talking to some young moms serendipitously like, ‘Why are people feeling so bad after they have a baby?’ I was literally putting questionnaires out and asking these women, and now they’re pouring into my offices. We’ve never had a waiting list at the Postpartum Stress Center like we’ve had in the past few years. I think it’s because women are giving themselves permission to ask for help and talk about it.

What makes postpartum depression different from normal depression?

In a way, it’s the same as any other depression, but it’s different for so many reasons that are hard to put into words. We’re talking about a combination of hormonal, psychological, psychosocial, and relational influences. It’s, ‘Not only am I depressed, but I’m not sleeping. I can’t eat. My husband and I haven’t touched in seven weeks. My mother was diagnosed with something terrible while I was pregnant.’ There are so many layers of influences that it can spiral very quickly. The biggest thing we worry about as clinicians is the urgency. She’s just had a baby, and she’s bleeding and lactating and discharging and she wants to go home and therapy is the last thing she wants. Her baby’s well-being is at stake and their relationship is at stake. Everything’s happening very quickly, and it needs to be attended to very quickly.

One of Kleiman’s tips for struggling moms. / Photograph by Mary Clare Fischer

There was a recent story in the Inquirer about how women of color don’t seek treatment for postpartum depression because they’re worried about child services taking their babies away — and that their fears may be justified. What do you say to those women?

It hurts my heart, especially after all these years of advocacy and trying to speak. I think a lot of local health care providers are still not asking the right questions and not creating a safe space for their patients. It’s just abominable how many women still report to us the things doctors are saying, like, ‘You’re not thinking of killing yourself, are you?’ This is 2019! And there are lots of really well-informed (or they think they’re well-informed) doctors who hear a woman say she’s having thoughts of hurting her baby and don’t know how to separate that from psychosis. They may overreact by sending her to the emergency room or something. So we need lots more education on that end.

When you’re making unhelpful comparisons. / Illustration by Molly McIntyre

And what I say with a painful heart is, we need to implore moms to find a safe space. There’s a few clinicians in private practice who I trust. There’s a new program at Drexel that is an intensive outpatient program. And, of course, we’ve been in the Bryn Mawr area for almost 30 years. But there are people down in Ardmore who don’t even know we’re here.

Finally, when I’m training experts in the field, we always say one of the best things you can do for a mom who’s depressed and so scared and when hopelessness feels so pervasive is connect with that person, look them in the eyes and say, ‘We know what this is and we know what to do and you’re not going to feel better tonight, but you will feel better.’ And that’s what this book is, too. It’s one big freaking hug.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.