They Told Me I May Never Walk Again. Now I Compete in Ironman Races.

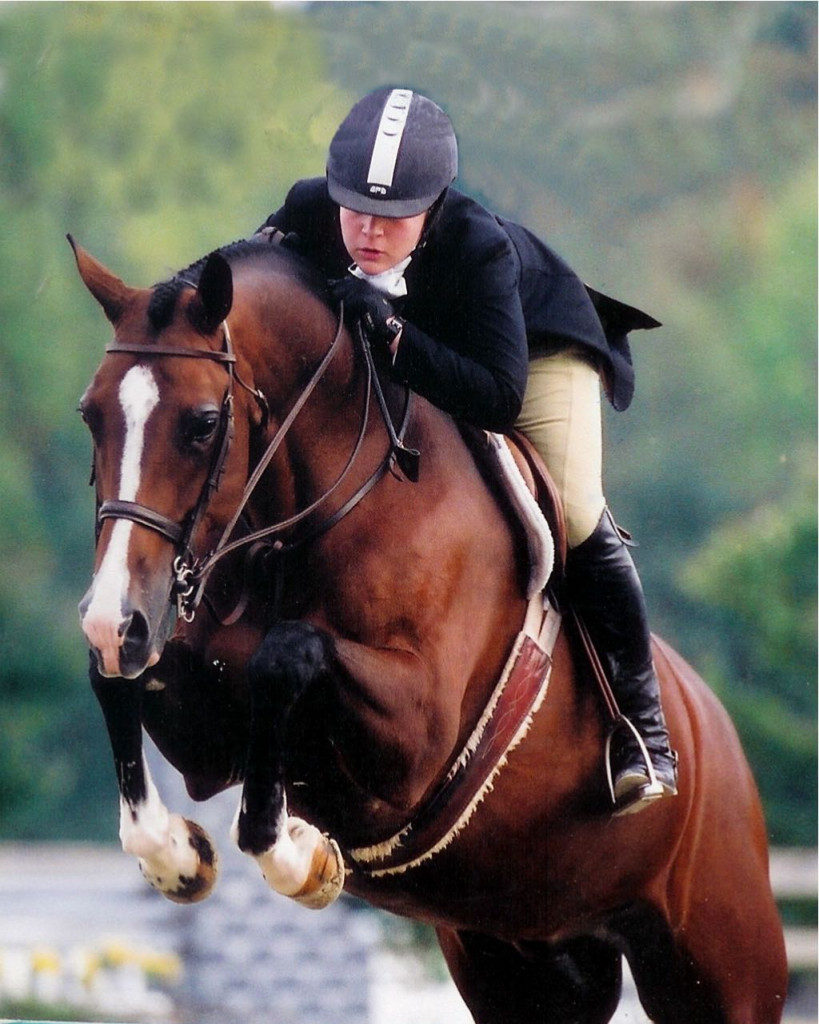

Philly gym owner Ali Cook Jackson was a nationally-ranked career equestrian. Then an unexpected and inexplicable injury changed her life.

Jackson completing an Ironman race in 2017 with her husband. Photograph courtesy Ali Cook Jackson.

Warning: A graphic image of a wound appears in the article below.

Ali Cook Jackson was mounting her horse. It was a move she’d done a million times before; riding horses had been her entire life since the age of five, and by the age of 17, she’d been nationally ranked for years.

This time when she mounted her horse, however, it felt different. Her left leg was stiff and the muscles cramped. Waves of pain rolled up her leg. Is this just a Charlie horse? she wondered.

Soon the pain was unbearable. Her parents drove her to the small-town hospital nearby. They were, once again, in Florida for a six weeks stay so Jackson could compete. At the hospital, the doctors told her it was probably just a Charlie horse, and since it did kind of feel like one, she believed them. She went home, popped some pain killers, and hoped the pain would die down.

“The rest of the night, I was up screaming in pain, and my lower left leg was as hard as a table,” says Jackson. “Something wasn’t right.”

Her parents drove her to a second, larger hospital in Tampa. This time, when the doctors looked at her leg, they told Jackson she needed surgery immediately. They prepared her for the worst: even with an operation, she might lose her leg.

Ali Cook Jackson was a nationally ranked equestrian. Photograph courtesy Ali Cook Jackson.

Jackson’s leg had been attacked by something called compartment syndrome. The pressure and swelling was cutting off the blood and oxygen flow to her leg. Acute compartment syndrome is typically caused by a severe injury, but up until this point, Jackson had always been perfectly healthy. When the doctors cut into her leg, the muscle beneath was black and necrotic — it had already started to die.

Though she came out of the surgery with her leg still attached, the news wasn’t all good: The doctors told Jackson that due to the intense swelling in her leg, they hadn’t been able to close up the incision — a seven-inch slice down the side of her calf muscle. Even worse, they told her it’d need to remain that way for three months while she was on bedrest. Then they told her that she may never walk again.

“At that point, it was just a devastating situation for many reasons, but I had no idea who I was without the riding,” says Jackson. “That is what I devoted my whole life to at that point, and it was great that I had my leg, but to hear I wouldn’t be able to walk again let alone get on a horse again was just beyond terrible.”

Returning home to Pennsylvania, Jackson didn’t have many school friends waiting for her; she’d always been traveling and had rarely spent time in the classroom. Her plan had been to skip college, go pro, and become a career equestrian. Instead, for the next three months, she sat in bed while people brought her food and her parents cleaned her wound.

Jackson spent three months on bedrest. Photograph courtesy Ali Cook Jackson.

“I was just in a daze of anger and depression and really, really scared,” says Jackson. “Because I’m just staring down looking at my muscle, which was still for a long time black and necrotic. I felt really weak, and that is not a feeling that I carried ever before the leg.”

Three months of bedrest and another three months of being in a wheelchair, and the athletic Jackson had soon gained over 80 pounds. Unwilling to submit to this future, she worked her way back to walking, first with two crutches, then with one, then on her own. She was determined to ride again.

“I bluntly said to the doctor, ‘Listen, I’m going to try and get back on this horse. I can walk. You told me there was a possibility I couldn’t walk. You told me there was a possibility I couldn’t have my leg. So I’m going to try to get back on the horse,'” says Jackson.

Over six months after closing up her leg, the doctors gave Jackson a date she was cleared to try mounting a horse again. On that day, Jackson flew back to Florida and got back up on her horse. Though she went on to compete again, at 80 pounds heavier it was much harder than before. Her leg was still numb from the knee down, and the strength she’d had to grip the horse before was gone. Though she stuck with it for over a year, her heart wasn’t in it like it had before.

“In my mind, I’m thinking I should be grateful and thankful, and meanwhile I was over [horseback riding],” says Jackson. “Looking back at it, I see that I was in a position where we didn’t know if I would have my leg coming out of that surgical room. I never wanted to be in that position again where I had so much to lose. By going back to riding, I was doing it all again, I was sacrificing my social life, I was sacrificing my family, I was sacrificing everything that could have been if I wasn’t so devoted.”

Left: Jackson post-weight gain. Right: Jackson during her first sprint triathlon. Photographs courtesy Ali Cook Jackson.

Still overweight and depressed, one day as a freshman at Villanova, she looked in the mirror and decided she was done feeling that way. Always a horseback rider, she’d never done much running or biking or any other kind of conventional exercise. So she joined Philadelphia Sports Club and began on the elliptical. She hated it. She tried spinning, and hated that at first too. After trying all different kinds of exercise, she ended up falling in love with running and spinning. To this day, she still can’t feel parts of her left foot. But by a year later, she’d lost all the excess weight, plus some.

Her sophomore year, her brother roped her into a sprint triathlon. She placed at her very first race. The competitive fire that had once pushed her in horseback riding was back; she was addicted. With a few triathlons under her belt, she attempted a half-Ironman, then a full Ironman.

In 2013, Jackson opened a gym, Never Give Up Training in Manayunk, that offers personal training and group fitness classes. Though Jackson now trains others to push their physical limits, her mission for the gym isn’t to turn people into hyper-dedicated athletes. Rather, she wants to help them find balance. After seeing how a life that’s focused on one goal can come crashing down, Jackson doesn’t want to see clients doing the same — whether that be through strict dieting or a rigid exercise schedule.

Jackson at the finish line of her third Ironman race. Photograph courtesy Ali Cook Jackson.

“You can’t work out all the time because then what’s going to happen to your professional career? Or your mental? Or your family life? You can’t put all your eggs in one basket,” says Jackson. “We want you to go out with your friends and have fun. We want you to go indulge in an Italian meal on your birthday. If you don’t love what you’re doing or you’re not enjoying life, you’re never going to be successful in accomplishing your goals.”

Like what you’re reading? Stay in touch with Be Well Philly—here’s how:

- Like Be Well Philly on Facebook

- Follow Be Well Philly on Twitter

- Follow Be Well Philly on Instagram

- Follow Be Well Philly on Pinterest

- Get the Be Well Philly Newsletter