Study: Graphic Cigarette Labels Help Smokers Remember Health Risks

Have you ever seen a pack of cigarettes from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Iran or Singapore? Sure, cigarettes seem basically the same around the world, but there is one main difference between a pack from these countries and one from America: they use graphic warning labels. The idea, of course, is that when a Canadian picks up a pack of smokes in hopes of dragging herself into deep relaxation, she may have second thoughts.

As federal tensions brew in D.C. on the subject, Penn’s making the headlines today as their Perelman School of Medicine releases a groundbreaking study. The study, the first of its kind in the U.S., looks at graphic warning labels on cigarette packaging and how they affect smoking habits.

Most basically, the researchers wanted to know two things: Do smokers get the intended message from warnings, and how do they do so?

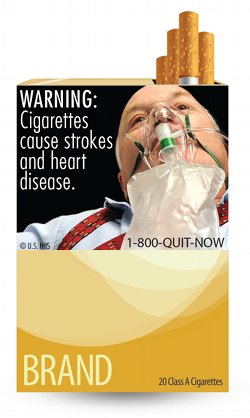

The study involved 200 current smokers who were exposed to either a text-only label made up of information that has been on packaging since 1985, or a new version with larger text and an image of a hospitalized patient on a ventilator, like the one pictured here. Then they used sophisticated eye-tracking technology and the less advanced (but equally telling!) method of asking participants to rewrite what the warning said.

Not surprisingly, they found a significant difference in how much people recalled of the text-only warning—just 50 percent of it—versus the warning with an image, which stimulated an 83 percent memory recall.

“In addition to showing the value of adding a graphic warning label, this research also provides valuable insight into how the warning labels may be effective, which may serve to create more effective warning labels in the future,” said Andrew A. Strasser, associate professor at the Department of Psychiatry at Penn and lead author of the new study.

Whether the memory recall of the label messaging leads to changes in smoking behavior was not explored in this study; that’s the topic of future Penn studies, say researchers. What the study shows, though, is that at the very least, the graphic images stick in the mind better. But you have to wonder: Is it because the labels are new, so smokers are more apt to pause to read and remember them, or because they are graphic? Once the novelty wears off, will the image-based labels be ignored, too?

Although a 2009 federal mandate required graphic warnings on cigarettes within the U.S., the implementation of this measure has been held up in the Supreme Court. Researchers hope that once graphic warnings are employed in the U.S., people will be better informed about smoking risks and maybe even encouraged to stop smoking. If that implementation ever happens.