The Continuing Adventures of Tony Auth

It was the Friday before a Redskins Super Bowl in the early ’80s, and that flap about whether the name “Redskins” was racist was all over the news. Tony Auth, the Pulitzer-winning editorial cartoonist at the Inquirer, wanted to put in his two cents. So he drew the most politically incorrect cartoon imaginable, of an NFL populated by teams that all had outrageously insulting, stereotypical names. There were, for instance, the San Francisco Fags, their helmets proudly sporting a guy making a fey hand gesture. The Philly team was the Wops. The cartoon went to press. That’s when the trouble began.

“A lot of people saw it in the production process,” Auth recalls. “Turns out the guys in the pressroom were up in arms.” Their objection? “They wanted to be the Pollocks, not the Wops.” Auth started to have doubts about the appropriateness of his drawing. Luckily, when he opened the next day’s paper, it wasn’t there. That’s when his then-editor, the legendary Gene Roberts, came into his office. He’d killed the cartoon. “What are you trying to do, Auth?” he asked. “Piss off every single reader on the same day?”

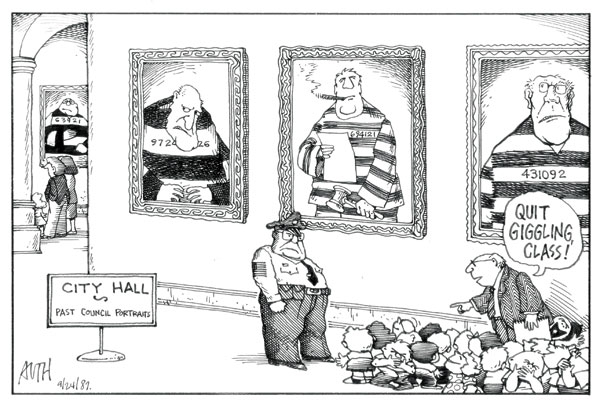

That was pretty much Tony Auth’s goal from the moment in 1971 when he started at the Inquirer. Over the next four decades, he’d win nearly every accolade and honor a cartoonist could dream of, from that Pulitzer (he was a finalist twice more) to the Herblock Prize (named for the legendary Washington Post cartoonist). Five days a week, his left-wing takes on war, politics, social justice and the city stared at us from the editorial page. He framed our worldview, guided our consciences—and infuriated the paper’s more conservative readers.

Then, last year, abruptly, he was gone, the victim—though he’d hate that term—of upheaval in the newspaper industry even more profound than the changeover from hot type. This month, a retrospective exhibit of his work goes on display at his new home, WHYY. A radio cartoonist? Why not? “Artists don’t retire,” says Auth.

Tony Auth on Tony Auth

At 71, William Anthony Auth Jr. is trim and white-bearded, with blue eyes to die for—sort of a fit Santa Claus. He doesn’t sound at all like his work, which is bold and opinionated and, well, cranky. His voice, instead, is soft and gentle, as you can hear on the video cartoons he makes for WHYY. “Tony turned out to have such a wonderful radio voice,” says Chris Satullo, the station’s vice president of news and civic dialogue. The two used to work together at the Inquirer; after management there killed two Auth cartoons late in 2011—not, as Gene Roberts had, for good reason, but merely “as excuses to make me uncomfortable,” Auth says—the cartoonist took a buyout, and the pair soon found themselves working together again.

“I thought there was a real possibility for using animation and cartoons in digital space to experiment, to draw readers and create motion,” Satullo explains. So while Auth continues to draw cartoons for Behind the Lines, his NewsWorks blog, they now come with a line or two—or more—of commentary on what he’s drawn. And he uses an app, Brushes, to record his process of creation, which he can then play back as video on the site. One recent example, prompted by this summer’s Johnny Depp movie, relates his childhood love affair with the Lone Ranger. Right there on your screen, you see his scant black outline of the masked avenger, then watch as, magically, colors fill in and detail deepens, right down to the trim on the cowboy boots. Auth also illustrates WHYY news stories—he especially enjoys accompanying Faye Flam’s science pieces—and has served as “the other reporter” on assignments at Citizens Bank Park and Rittenhouse Square, jotting visual addenda and taking photos to later be used in watercolors. His sketches are wry and sophisticated even when their subjects aren’t; he makes fun of Philadelphia in a way we only allow fellow Philadelphians to.

Auth’s Lone Ranger piece refers to a crucial segment of his Ohio childhood. At age five, he was seriously ill, bedridden with rheumatic fever for a year and a half. TV hadn’t become mainstream yet, so he listened to the radio. “It was fantasy land,” he says. His mother decided he should learn to draw, and brought him pencils and crayons and paper. He started sketching the characters from his beloved radio shows and comic books. “I realized how very different all these worlds looked—Superman, the Red Raider, Terry and the Pirates,” he says. He would study and copy one world—how the artist drew buildings and figures, used light and color and shadow—then move on to the next.

Later, at Catholic school—his household, he says, was religious and “very conservative”—he was always the best artist in class. He recalls a second-grade assignment to create a winter scene for which he drew a cabin in the woods, with smoke from the chimney rising at an angle. “The nun looked at it and said the smoke should go straight up. I said, ‘Sister, there’s a breeze.’” She said unless the smoke rose straight up, he’d fail the assignment. Auth refused to bow: “She could not decide how my smoke should go.”

That childhood defiance never deserted him. His family—his father was a Firestone exec, and he had one younger brother—moved to California when he was nine. He went to UCLA after high school, and got a job doing medical illustrations when he graduated. But it was the era of the Vietnam War: “Such a time!” he says. “The new feminist movement, gay rights, civil rights—everybody I knew read all the time, engaged all the time.” While at UCLA, he’d done some cartoons for the student newspaper, the Daily Bruin. Now he branched out, drawing for an alt-weekly. “I fell in love with it,” he says.

He showed his work to Paul Conrad, then the cartoonist at the L.A. Times, who advised him to increase his output and to keep it simple. For the next year, even though he’d graduated, he did three cartoons a week, for free, for the Daily Bruin. After a long series of fits and starts—there were only 200 full-time editorial cartoonists in the country in those days (today there are 85)—he heard about an opening at the Inquirer, and “essentially invited myself for a week-long job interview.” They put him on a plane home at the end of the week, but he’d no sooner arrived than then-executive editor Creed Black called to say, “We miss you.” He was in. Weeks later, he was syndicated. Within five years, he’d won the Pulitzer Prize.

For the next four decades, Tony Auth drew Philadelphia for us. If you think that’s easy, you don’t understand the art of the cartoon. David Leopold, the curator of the WHYY exhibit—it was originally mounted in 2012 at Doylestown’s Michener Art Museum—does, now that he’s gone through 10,000 of Auth’s cartoons with the artist at his side. “I mostly deal with 20th-century American art,” explains Leopold, who lives in Bucks County and has helmed exhibits in New York City, Los Angeles and Europe, among other places. “There’s a lot of ambiguity in it, a lot of give. But Tony’s work—if you don’t understand it in 10 seconds, I’ve picked the wrong piece. How do you do a show where there’s no ambiguity?”

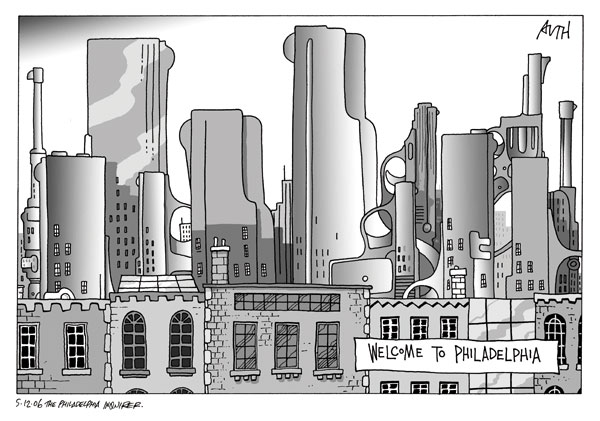

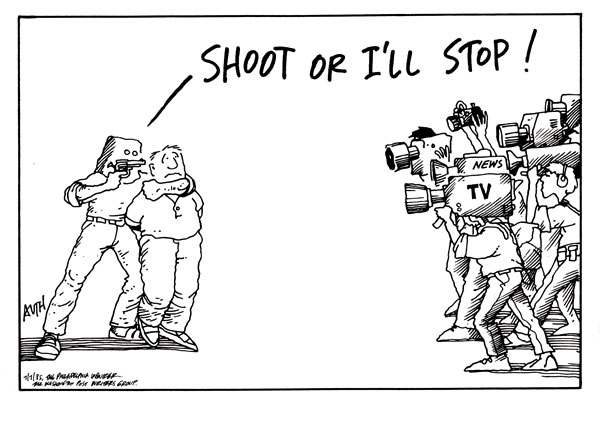

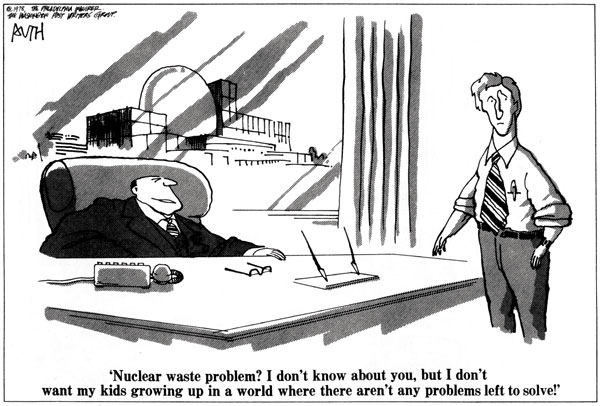

In the end, Leopold based the exhibit (which will run at WHYY through November 8th, with a companion exhibit of Philadelphia-centric cartoons at the Philadelphia History Museum from October 11th through January) on what had been the artist’s home for so many years: the newspaper. He had Auth hand-letter, in his distinctive block print, categories the cartoons naturally fell into: Vietnam, Nixon, Economics, Civil Rights, Faith, Guns … Beneath these “headlines” were Auth’s takes on each subject across the decades. “You don’t read a newspaper straight through,” Leopold says. “You might look at the first page, then go to sports, or art. People can interact with the exhibit the way they do a newspaper, according to their interests.”

The key to cartooning, like so much of life, is to make it look easy. Auth learned from his early mentor, Conrad, that the labor behind his art should never show—however much work that took. At the Inquirer, Auth was notorious for bypassing his editors, turning instead for critiques of sketches to reporters, photographers, columnists. It’s a process he’s continued at WHYY.

“We have a young newsroom,” says Satullo. “Most of the people there are maybe half Tony’s age. It’s wonderful to see the joy they have in working together.” Whereas plenty of older journalists are cowed or angered by their field’s radical technological mutations (hello, Stu Bykofsky!), Auth, as Satullo puts it, “surfs on top of that change and yells ‘Cowabunga!’” It’s an image Auth really should draw.

To a lot of journalists, the future of their profession looks worse than dismal. “It’s like it’s 150 years ago and you’re in whale blubber,” says Leopold. “Newspapers as we know them are done. It’s no longer the way we deliver the news.”

That’s one reason Auth was ready to leave the Inquirer: He likes to be part of the conversation, and the conversation was no longer where it once had been. When online commenting at the paper began, readers who would call to let him know what they thought of his work stopped, abruptly. He needs feedback; he thrives on it. “I wanted to try other forms of cartooning,” he says. “Philly.com was not the place.”

He wonders himself what the future of journalism might be. “The print model doesn’t look viable,” he muses. “There have always been irreverent cartoons. But how to make a living at it?” Some media critics think the role of the political cartoon has been usurped by TV programs like The Colbert Report and The Daily Show. “I find that deplorable,” Auth says in a less-than-sunny moment. “Drawing as an act of satire is different from the spoken word.”

Satullo says Auth is still figuring out how best to engage in his new role at WHYY; he’s pushing the station’s “digital artist in residence” to make more use of Facebook and Twitter. The videos Auth makes are a plunge into a different medium; he takes the static cartoon image and grows it—and lets observers in on his creative process. It’s one more way to converse.

More than 85,000 visitors trekked to the Michener Museum during Auth’s 2012 retrospective. “Tony’s work has become a part of people’s lives,” says Leopold. “You share your breakfast table with him.” But beyond that, “He has a remarkably high batting average for work that has stood the test of time.” Auth’s curator says the reason is simple: “He’s interested in human nature, not just in picking a side.”

Auth shares his Wynnewood home with Eliza Drake Auth, the landscape and portrait painter who’s been his wife for more than 30 years. One of their daughters teaches preschool in Gulph Mills; the other works for the environmental nonprofit Worldwatch Institute. Like their dad, they’re saving the world, in their own ways.

Forty years of chronicling humanity’s—and this city’s—foibles might seem sure to make a man cynical. Auth isn’t immune to darker feelings. Twice during our interview, he teared up. It’s none of your business what about. Even our municipal court jester deserves a little privacy.

But at the heart of any cartoonist’s mission is boundless optimism: He holds a mirror up to us in hopes we’ll change.

“I remember clearly someone saying to me years ago, ‘What are you going to do when Lyndon Johnson isn’t president anymore?’” says Auth. “Somebody has said that to me about every president since.” Human idiocy is bad for the species, but great for cartooning.