Why Does Neil Theobald Think Football Will Save Temple?

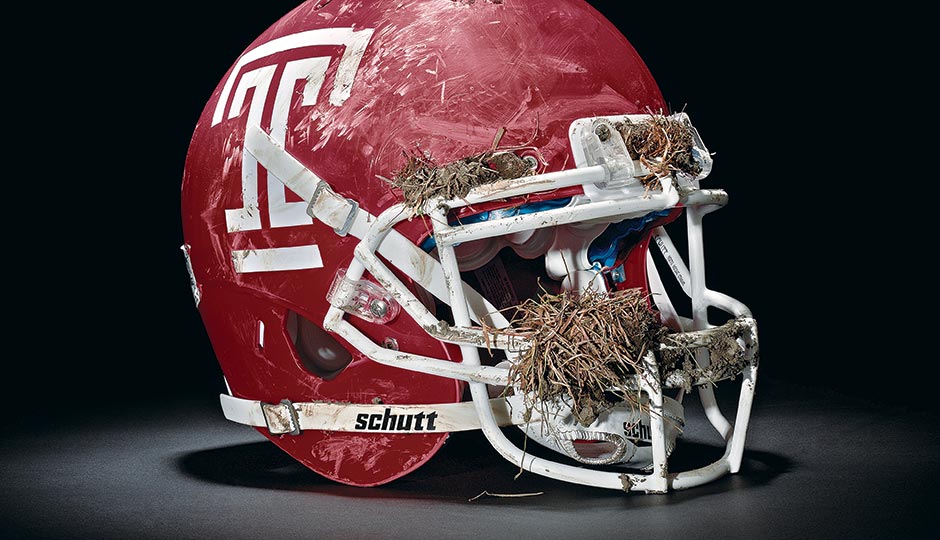

Photography by Clint Blowers

It was a date that would live in infamy.

The news hit the scholar-athletes gathered in Temple University’s Student Pavilion on December 6th of last year like a brick to the gut: The sports teams they’d been recruited for, trained for, worked for, played for, were being eliminated — “Chop, boom, you’re gone,” read the headline in the Temple News. Seven teams went poof: men’s crew, women’s rowing, softball, baseball, men’s gymnastics, and men’s indoor and outdoor track and field. Dozens of young hearts — along with those of their coaches — were broken as the university’s new athletic director, Kevin Clark, wielded the ax in a brief, succinct speech. And everybody knew where to lay the blame. “Make no mistake: Football drove cuts” was the headline on a student-newspaper editorial. The Inquirer’s Bob Ford chimed in: “No kidding they had to cut sports to save money. They just didn’t cut the one they should have.”

It seemed a logical conclusion. The seven eliminated teams cost about $3 million, or just seven percent of the athletic budget. One hundred fifty athletes and nine full-time coaches were affected; the football team alone has 115 roster spots — 85 of them with scholarships — plus 29 coaches and assistants. Clark, however, said the cuts were being made to bring the school into line with Title IX requirements and the other members of Temple’s new American Athletic Conference, none of which fielded more varsity teams than Temple did. The savings, he insisted, would be used to upgrade all the remaining teams, not just football, which had recently concluded a 2-and-10 season under first-year coach Matt Rhule.

Temple’s new president, Neil Theobald, was equally adamant, telling the New York Times, “I can say unequivocally, that I never considered football in this decision.” He wrote in an op-ed for the Inquirer: “Football is not the reason for this move.” And really, what school would put its eggs in football’s basket, in an era when the NFL is paying out millions to players suffering from concussions, when the NCAA is crumbling under lawsuits from ex-players, when teams are accused of being havens for rapists and abusers, when President Obama himself has said he wouldn’t let a son of his play the game?

But as contrary as it sounds, as Temple nears the end of its 130th year of existence — and the fourth straight year in which the state legislature has refused to increase its funding — football could turn out to be its savior. The future of what Theobald likes to call “Philadelphia’s Public University” might be riding on the broad, padded shoulders of the student-athletes just about everybody seems to resent.

THE FIRST THING you need to know about Neil Theobald is that he’s a numbers guy. That’s his academic specialty; his doctorate is in higher-education financing. He gets hired to figure out how schools can pay for themselves. He’s also not from around here. He grew up in Peoria, Illinois; his dad worked at the Caterpillar tractor plant, and his mom was a bank teller. When he came home from high school and announced that anonymous donors would make it possible for him to attend tiny, prestigious Trinity College in far-off Connecticut on a full scholarship, his dad was bewildered. “Why would you do that?” he asked, pointing out that Neil had already been accepted into Caterpillar’s electrician apprenticeship.

Money changes everything. Theobald knows that. “Those donors took my life in a wildly different direction,” he says, sitting in the high-ceilinged office in Sullivan Hall that’s been his since January 2013. “I just got on a totally different escalator. That’s what we’re trying to do at Temple.”

His past would seem to make the solid Midwesterner a perfect fit for the school on North Broad Street, which had the humblest of beginnings back in 1884, when a young neighborhood man asked charismatic Baptist minister Russell Conwell to tutor him. Conwell took on the job, and before long, dozens of students were attending his night classes in hopes of bettering their lives.

That’s still Temple’s mission; historically, it’s served the working class, more rough-and-tumble than Penn or Drexel, utterly without airs. So is Theobald; for a college president, he’s shockingly unpretentious. A lot of Temple people use the word “refreshing” to describe him. From his first days on campus, he asked everyone he met, with Midwestern candor: “What are the problems here? How can we deal with them?”

Unsurprisingly, his earliest initiatives have to do with cost. “The biggest problem in our society,” he says, “is the level of student debt.” Debt-burdened graduates “can’t buy houses, can’t buy cars, can’t get married, can’t start their careers, because they have to service their debt. And that’s impacting the economy.”

So Theobald is pushing his new “Fly in 4” plan. Research shows that college students who work at a job for more than 15 hours a week have lower graduation rates and increased student debt. So low-income Temple students are getting paid not to work, receiving scholarships to replace lost wages in hopes they’ll graduate in four years and debt-free.

Don’t think this came about because the school is going begging. “We had 27,000 applications for 4,500 slots this past year,” Theobald says. Temple is benefiting from a number of national trends. The Chronicle of Higher Education says urban schools are hot right now — they provide access to better internships and research projects, not to mention nightlife. And Temple is a poster child for campus diversity.

Where Temple falters is in the size of its endowment. Drexel has $586 million in invested financial assets. Penn State and Pitt, both state-supported schools like Temple, each have $3 billion; Penn has $7.7 billion. Temple has a lowly $324 million. When times get tough, as they are now, colleges can raise tuition or dip into their endowments. Temple hates doing the former, in deference to its historic mission. And it can’t afford to do the latter, with so little squirreled away.

There is one other option: A school can go after alumni donations. Penn State, despite its recent woes, just successfully hit its $2 billion target in a “For the Future” campaign to add to its nest egg. Temple’s current campaign seeks just $100 mil. What does Penn State have that Temple doesn’t? For one thing, its football team. Even with the program’s well-publicized problems, Penn State is fifth in the nation in football attendance, averaging 96,587 fans per game last season. Temple draws about 22,000 fans to home games; they rattle around in 68,532-seat Lincoln Financial Field. Penn State football generated $58.9 million in revenue in FY 2011; the athletic department kicked in another $55 million from royalties, ads, sponsorships and licensing. When’s the last time you saw a Temple car magnet?

There are other differences between the two schools. Happy Valley is Shangri-la, 40,000 undergrads let loose in an 8,500-acre romper room of sports and sex and beer. Temple is crammed onto just over a hundred acres of asphalt, stuck between Broad Street and a public-housing clump. And for most of its existence, Temple was a commuter college, with students tucking classes around families and jobs. When Temple law professor Mark Rahdert arrived in 1984, “There were practically no resident students,” he says. Today, 12,000 of Temple’s 28,000 undergrads live on or near campus, with the number ticking upward each year.

As a result, this is much more like a classic college campus than it used to be. The newest dorm, $216 million Morgan Hall, is home to almost 1,300 kids. Visit the campus and you’ll see construction everywhere, along with sidewalk cleaners, window washers, painters, and dozens of private Temple cops and security guards. Even on a sleepy summer morning, walkways are full of life. Parents who went here return with their offspring for admissions visits and don’t recognize the place. Still to come: a vast green “campus center” where frat bros will toss Frisbees, profs will hold outdoor classes, researchers will sip lattes, co-eds will sunbathe — and the loyalty that brings in alumni dollars will be built.

NOT EVERYONE IS THRILLED with Temple’s new popularity. The school has a lengthy history of troubled relations with its neighbors. The home of immigrant industrial workers at the turn of the 20th century, North Philly fell on hard times after World War II. In the 1950s, Temple went so far as to purchase a new, suburban site in Cheltenham before president Robert L. Johnson renewed the school’s commitment to its deteriorating neighborhood. In the ’60s, with racial tensions erupting into riots along Columbia Avenue, activists demanded to know just how big Temple intended to get. Local representatives and the school couldn’t agree on a boundary, so the state stepped in. Lines were drawn: Temple wouldn’t intrude into the public housing on its east side, and it wouldn’t cross Broad Street to the west. “Temple honored that agreement for quite a few years,” says emeritus professor James Hilty, Temple’s chief historian.

Former mayor John Street represented the fifth Council district, which includes Temple, for almost 20 years. In the ’70s, he says, “It was the policy of the city not to make improvements there. It was too far gone; there was too much blight.” Redlining left residents unable to sell their properties; slum landlords moved in; there was little code enforcement. Relations between Temple and its neighbors were “very contentious”: “There had been all this mass condemnation of properties in West Philadelphia. Penn and Drexel just gobbled up neighborhoods. North Philadelphia was worried that would happen here.”

There was also, notes Street, who now teaches political science at Temple, the “natural tension” between rowdy beer-and-bong-fond students and longtime residents. He remembers neighbors complaining that Owls were urinating on them from houses at Broad and Norris; the school was “very disrespectful of the community.”

The ’70s were also when Temple football, which had been a regional power in the 1920s and ’30s, experienced a renaissance under coach Wayne Hardin. His Owls were 80-52-3 over 13 years, playing home games at Veterans Stadium in South Philly. More than 55,000 fans saw the Cherry and White beat California in the Garden State Bowl in 1979, the year the team had its winningest record at 10-and-2.

It was downhill from there. Formerly an independent, the team had joined the lofty Big East in 1991. (Temple’s other varsity sports competed in the Atlantic 10.) But in 2001, “We were asked to leave,” says Bill Bradshaw, who was hired as Temple’s athletic director the following year. With the Vet due to be razed, Temple moved its home games to Lincoln Financial Field for the 2003 season. Then, in January of 2005, based, Bradshaw says, on “the poor performance of the team and the hemorrhaging of money,” the school appointed a committee to decide whether it should drop the football program completely. Its members voted to play on.

Plenty of people still wish that vote had gone the other way — including, no doubt, most members of the sports teams that got cut last year. (The men’s and women’s crew teams were rescued by a $3 million donation from board member Gerry Lenfest and $2.5 million from the city.) Instead, Temple doubled down on football, hiring Virginia’s young defensive coordinator, Al Golden, a Penn State alum and Joe Paterno protégé, as head coach.

In four years, Golden roused the team to 9-and-4 and the 2009 EagleBank Bowl. The next year, the Owls went 8-and-4 — and Golden headed south to coach at the University of Miami, despite a contract extension reportedly worth $1.2 million a year. (Theobald’s salary is $450,000 this fiscal year, plus $200,000 in deferred compensation — in the middle of the pack for public university chiefs.)

Except for die-hard Owl football fans — and there are die-hard Owl football fans — nobody much noticed Golden’s desertion. Perhaps because of our borderline-insane Eagles love, Philly has never been a college football town. Besides, in the midst of the team’s return to respectability, the neighborhood had been undergoing a revival of its own.

IN 2007, CHEF Marc Vetri and two partners opened an Italian restaurant called Osteria in the 600 block of North Broad Street, a.k.a. the ends of the earth. This wasn’t Fairmount, or even Fishtown; it was flat-out North Philly, down the street from the shell of the Divine Lorraine Hotel. The Inquirer’s Craig LaBan, in his first review, said Osteria’s margherita pie could be “the pizza that saved North Broad Street.” Temple owes a lot to that pie.

A dozen blocks further north, the school’s Broad Street boundary had been breached in the ’90s by a dorm at Broad and Susquehanna and the opening of the Liacouras Center, a 10,000-seat venue that’s housed pro wrestling, rap concerts and the men’s basketball team. That was followed by Avenue North, a movie theater/retail/restaurant complex at the southern foot of campus. Stephen Starr and Vetri developed the old Wilkie Buick site; Eric Blumenfeld bought the Metropolitan Opera House and jump-started stalled plans for the Divine Lorraine. Bart Blatstein dreams of a European village atop the abandoned Inquirer building. Bit by bit, the vacancies in the North Broad landscape are filling in.

Theobald, who frequently walks to Temple from his Center City home, says the school considers its environs part of what makes it unique: “We’re a public research university in a large urban area. New York doesn’t have that. Boston doesn’t have that. D.C. doesn’t have that.” The school has educated Philly’s middle-class backbone — dentists, nurses, teachers — for generations; one in seven area college grads is a Temple alum. Temple’s hospital system is the city’s de facto charity ward, providing $68 million in gratis and under-reimbursed care in FY 2013. The university had $230 million in research expenditures that fiscal year. “There’s potential here that people aren’t aware of,” Theobald says.

“We’re in the shadow of Penn,” Rahdert agrees. “The collective vision of the faculty is that the further you get from Philadelphia, the better Temple’s reputation gets.” Exhibit A: In July, Temple researchers announced they’d become the first in the world to successfully eliminate the HIV virus from cultured human cells.

To get that sort of good news out, Theobald created a new position — vice president for strategic marketing and communications — and brought in Karen Clarke from a similar role at the University of Houston. She sees her job as “telling Temple’s story in new and important ways.” Houston and Temple share some of the same issues, she notes: “I think of it as a kind of adolescent mentality. It’s as though they’re saying, ‘We’re not sure what we’re good at.’ They’re self-deprecating.” Having Penn as your neighbor will do that.

But as Clarke’s new marketing campaigns point out, kids today are proud to be Temple Made. Freshman GPAs are at an all-time high. Undergrads from other states and overseas made up 20 percent of last year’s student body, up from 12 percent in 1983. Over the summer, the school’s Twitter account reveled in delirious newbies:

@KyleJMc37: Moving into my dorm @ Temple in exactly 2 wks. So excited to spend the next 4 yrs there

@_tweedle_de: I love you @TempleUniv I can’t wait I’m too excited :) :)

Where the hell do these kids think they’re going — Happy Valley? They’re having so much fun on campus these days that Theobald had to cancel the annual Spring Fling due to drinking and rowdiness. The only thing North Broad needs now is a line of underclassmen in letter sweaters kicking through autumn leaves to the homecoming game.

WHICH BRINGS UP the touchy subject of an on-campus football stadium. Temple’s contract to use the Linc for home games expires after 2017. In an April interview in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Theobald said Eagles management was nearly doubling the rent, to $3 million a year, and demanding an additional $12 million for renovations. “We’re not about to give them that kind of money,” he said. The Eagles retorted that they hadn’t held any talks with Temple about the contract in more than a year. “We do not consider statements in the press to be negotiations with us,” Eagles president Don Smolenski snipped.

Temple’s total athletic budget has already swelled from $25 million in 2010 to $44 million in 2014. Joel Maxcy, a professor in the school of tourism and hospitality management, told the Philadelphia Business Journal that a new North Philly stadium would cost some $200 million. That makes even the hiked-up Linc rent look cheap.

“You don’t have to build a $200 million stadium,” Kevin Clark counters. “You can build a nice, intimate 30,000-to-40,000-seat stadium for $80 million or $100 million. That’s what they did at Central Florida and Tulane” — two other American Athletic Conference schools.

“Look,” says Theobald. “We have a good relationship with the Eagles. We’ll be at the Linc for four more years. But the rent will be getting higher. This is student money, public money. The only responsible thing is to look for alternatives. One possibility is that we would build our own stadium on campus. Every college would want to have that.”

“We’d love a stadium on campus,” says John Campolongo, ’92, a managing director at asset management firm SEI and past president of Temple’s alumni association. “It’s a great way to bring alumni back and keep students involved.” But if you’ve just spent a year insisting it wasn’t football’s fault that baseball and softball got cut, how do you build football a new home?

Even thornier than that problem, where the hell would you put it? “A stadium isn’t just 100 yards long,” Hilty points out. “You have to figure in infrastructure, parking … you’d need four whole city blocks.” When Temple bought William Penn High in June, stadium rumors swirled. Temple insists it has no such plans for that site, but it’s wary of accusations of neighborhood-gobbling. Residents who once couldn’t give their homes away complain they can’t afford to live here now; the median price of a house near campus has shot from $17,000 in 2000 to more than $100,000 last year. In September, the school announced a 25-square-block expansion of the area patrolled by campus police. The irony isn’t lost on anyone at the school; the citizens it’s displacing are those it was founded to serve.

Temple tries to keep peace with its neighbors. In June, HUD announced a real plum for the area: a $30 million grant to replace 147 units of public housing on the east side of campus with 297 new mixed-income homes, a workforce training center, a community center, retail space, underground parking and a one-acre park. Temple pledged $1.2 million to the project. City Council President Darrell Clarke, who now represents what was John Street’s district, worked hard to bring all the parties to the table and develop the grant proposal. Was there finally a tentative peace between town and gown?

Um, no. Before the month was out, a coalition of neighborhood activists and residents sought an injunction to block the William Penn High sale, accusing Clarke of pulling strings to push the deal through. Clarke’s office called the allegations “baseless and false.” So much for détente.

The sale now seems poised to go through. But there was another, worse blow to Temple over the summer. Just weeks after he’d delivered the spring commencement speech, Lewis Katz, the university’s biggest donor and supporter, member of the board of directors and longtime chair of its athletic committee, died in a plane crash. “He’s irreplaceable,” Theobald says. “It’s a huge loss.”

LAST WINTER, very uncharacteristically, Temple’s men’s basketball team tanked, going 9-and-22 in its eighth season under Fran Dunphy (who left Penn to coach here). Historically, the team has been very good; it has the sixth winningest record in the NCAA.

Basketball programs are much less expensive than football, and the college hoops scene is a lot more fluid; every NCAA tourney features some upstart like Wichita State. Temple already has the Liacouras Center, and a luxe basketball practice facility that’s been renovated to the tune of $58 million. What with the Big Five’s intense cross-town rivalries and the hallowed Palestra, “We say Philadelphia is the capital of college basketball,” says Bradshaw. Which raises the question: Why would Temple bank on football instead? “Whenever there’s a mystery in college sports,” says Bradshaw, “go to the green.”

Critics of big-time college sports say only a handful of schools turn a profit from them. But money isn’t all that’s at stake. In its first season in the American, Temple football had a record number of televised games. “There’s a national appetite for football,” says Karen Clarke. “It offers the opportunity for national exposure that no other sport affords.” Clarke’s previous work history includes the University of South Florida as well as Houston. “I’m from the South,” she says. “Football is big. You don’t question anything about it. I don’t understand why it would seem odd to anyone to look at football as a positive.”

Theobald brought A.D. Kevin Clark along with him from Indiana, a school in the Big Ten — Penn State’s conference — where football might be even bigger than it is down South. “You look at Big Ten schools like Michigan and Penn State,” the A.D. says, “and you get a good sense of what it takes to have a successful program. You see the excitement and visibility football brings to campus. You can learn from them.”

Besides, there’s a template for how to turn a D-1 football program around. In 2008, driven by fear it would get kicked out of its conference, the mighty ACC, Duke set out to revamp its perennially putrid football team. The university seduced legendary SEC coach David Cutcliffe — mentor to Eli and Peyton Manning — away from Tennessee with a salary of $1.5 million, then overhauled the team’s practice facility and stadium. Cutcliffe changed the team culture (at their first practice, he told players they were “the fattest, softest football team I’ve ever seen in my life”) and ramped up recruiting. Three years later, Duke football pulled in $21.9 million in revenue. It made $1.7 million in a 2012 trip to the Belk Bowl, and almost $4 million from the 2013 Chick-fil-A Bowl, a thrilling throw-fest in which Johnny Manziel’s Texas A&M Aggies just barely eked out a 52-48 win.

The potential for Temple football to generate serious income is there. The American Athletic Conference has a seven-year, $126 million TV deal with ESPN to air football and basketball. (Temple’s old conference, the Big East, turned down a 2011 TV deal for $1.17 billion before seven Catholic schools departed, taking the name with them and leaving the husk to form the American.) This may only be Coach Rhule’s second year, but he was here for all five years of Golden’s tenure, plus one season under successor Steve Addazio, so he’s a familiar face. Like Golden, he’s a Penn State alum (a walk-on linebacker!) schooled at Joe Pa’s knee. He’s continued the emphasis on classroom performance that Golden began. In July, Temple sophomore quarterback P.J. Walker was named to the watch list for the Maxwell Award — presented annually to the best college player in the country. Rhule’s 2015 recruiting class is the finest the school has had in decades. In its season opener, Temple thumped Vanderbilt — an SEC school — 37-to-7.

Ask about a stadium on campus, though, and the boyishly handsome Rhule steps right into central casting: “Wherever they tell us to play, I’ll play. All we need is two acres and a ball.” Rudy! Rudy! Rudy!

IT MAY SEEM CRAZY to keep talking about football when Temple has so much more going for it right now. But as Theobald says, sports are the “front porch” of a university; they build the brand and attract new students and alumni dollars the way nothing else can. He says cutting those teams was “the hardest decision I’ve ever made in higher education. It was the right thing to do. But explaining that to the kids … ”

Historian James Hilty says Temple “has never had enough money to deal with all its ambition.” In making the cuts, “Neil was saying: I’ve been around the Big Ten. If you’re going to compete, you better put up the money. It was a hard-hearted decision that was made in a hard-hearted way.”

But Theobald isn’t a visionary; he’s a numbers guy. In the larger sense, he told the truth: The cuts weren’t because of football. They were because of the harsh new reality of college finances.

You know who would appreciate him? Temple founder Russell Conwell, who made his name as an orator delivering his “Acres of Diamonds” speech up and down the East Coast. It’s a windy, winding lecture exhorting listeners to strive for wealth:

You and I know there are some things more valuable than money; of course, we do. … Nevertheless, the man of common sense also knows that there is not any one of those things that is not greatly enhanced by the use of money. Money is power.

If Temple builds a stadium, will they come to North Broad — the new students, the ace recruits, the deep-pocketed alumni, and the hotels and restaurants and bars to house and feed and amuse them? Football profits could help Theobald achieve his goal of hiring more tenure-track faculty. They could improve facilities for non-revenue sports like fencing and crew. They could build the endowment, fund scholarships, underwrite neighborhood public schools and ease community relations. This could be Temple’s moment, its cue to step out of the shadows and into the sun.

“No final decision has been made,” John Campolongo says coyly.

Bradshaw, less cautious, expects that stadium to rise, and soon: “There will be an announcement before the end of the year,” he predicts. Kevin Clark insists there’s no such announcement in the works. Still …

“They’ve got to do something,” says Street, who as mayor put together the deal for the Linc’s financing. “I’m outraged that the Eagles are treating Temple like that.” He’d plunk a new stadium down at 15th and Montgomery: “It’s like my mother used to say — God bless the child that’s got his own.”

Originally published as “This Is Temple’s Savior?” in the October 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.