George Norcross: The Man Who Destroyed Democracy

In a story this profane, a story about power and legacy, fathers and sons, a story in which F-bombs rain down in a kind of grid pattern designed to make sure offense is taken, it’s probably best to warm up, first, with an inappropriate reference to the female anatomy.

In this bit, George Norcross III, one of the new owners of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Daily News and philly.com, calls Bill Ross on his cell phone and asks him to put out a press release.

“I want you,” he says, “to condemn the Teamsters.”

There was an inflatable rat going up outside the Inquirer building on North Broad Street—the why doesn’t really matter—and Norcross wanted Ross’s help. This struck Ross as odd. As executive director of the Newspaper Guild, representing editorial, advertising, circulation and finance employees, Ross generally tries not to hurl invective at the unions representing other disciplines.

“No,” he said.

But the thing about Norcross is, he asks. Then he cajoles. Sometimes, if circumstances dictate, he makes an offer. According to Ross, Norcross called back and said, “Look, if you put out the release, I’ll let you pick the brand of coffee we provide free to employees.”

Now, in terms of incentives to compromise on his union principles, picking a type of coffee doesn’t reach Ross’s bar. He remained a no. The next day, another newspaper union issued a release critical of the Teamsters. So Norcross called again. He made an assessment of Ross, this man with whom he would later be negotiating, and went right after his manhood.

“You’re a pussy,” he said.

The relationship between Ross and Norcross, such as it is, has never really improved, especially considering the thing with the water bottle.

That event took place in person, in the conference room down the hall from Ross’s office, where one day last spring Norcross showed up, unannounced. He told Ross that the new ownership group needed to renegotiate all the preexisting contracts it had inherited when it bought the company weeks before. Moreover, he wanted Ross and the Newspaper Guild to let go of any seniority protections: If there were layoffs, tenure should offer no sanctuary.

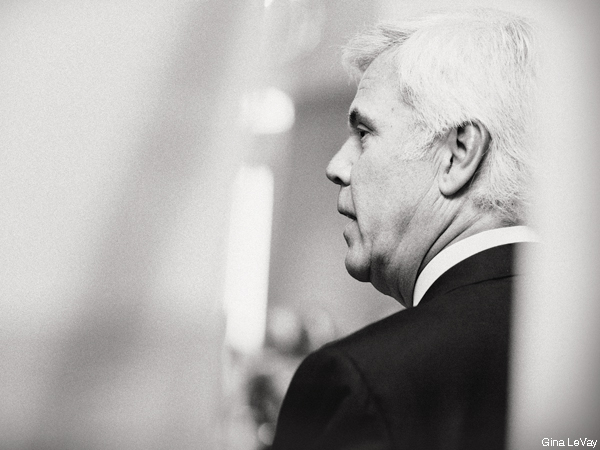

He sat there, confident, in French cuffs, swigging from a water bottle, his pile of white hair looming, and he said to Ross, “My father used to say that seniority will be the death of the labor movement as we know it.”

Norcross’s late father, George Norcross Jr., served as president of the AFL-CIO unions in South Jersey. But Ross didn’t believe any labor leader would attack seniority, retorting: “I’m sure your dad never said that.”

“We need to get rid of the deadwood,” Norcross responded. “We’re paying your members just to breathe.”

“You’re talking to me like I’m a jerk-off,” said Ross at one point.

“No, not at all,” Norcross shot back. “I think you’re the smartest labor guy I ever worked with.”

“Now you’re just patronizing me,” Ross retorted. He ended the meeting, “Why don’t you just get the fuck out—and take your water bottle with you.”

Norcross responded by securing his water bottle tightly in his right hand and flinging it off the far wall—nowhere near Ross, but in a sense, right at his crotch. Then he walked out the door.

There are some disagreements over the particulars of these stories. (Norcross, for instance, doesn’t remember offering Ross a chance to pick the brand of coffee.) But what everyone can agree on is that both stories sound just like what we’d expect of George Norcross—a man many of us have heard of, and none of us actually knows.

An insurance executive and the unquestioned leader of the South Jersey Democratic party, Norcross holds unshakable influence over offices from the mayor of Collingswood to the Camden County freeholders to the state senate. Within New Jersey, he boasts true omnipotence—his alliances with North Jersey Democrats are so strong that no governor can ignore his wants, and he is second only to Governor Chris Christie in terms of influence. But despite his great power over public offices, he has seemed to prefer that we not know him. For decades, through the ’80s, ’90s and early ’00s, Norcross kept to the shadows. He built a fortune in the relative anonymity of the insurance business. He led meetings in the political back rooms. And the little that leaked out to the rest of us cast him in villainous terms. On clandestine law-enforcement recordings, made public in 2005, Norcross boasted of his power and promised to make a profane end of his opponents—rapid-firing F-bombs and saying he’d see to it that those who crossed him were “punished,” “fired” and “crushed.”

He used the kind of language we associate with the Mob, and practiced an old-school bossism in which he engineered and exacted political victories and revenge. And this image of him, as a man reveling in power and gluttonous for more, seemed indelible. But in the past few years, something shifted.

George Norcross III started behaving in new and surprising ways. He emerged from the political back rooms. He started speaking publicly, eloquently, delivering a new narrative, in which he is the devoted son of a dedicated father, in which he has always held our best interests at heart. He started pursuing community-building initiatives in poverty-stricken Camden. He even extended his reach across the river and into Philadelphia, where this past year he became a driving owner behind the new group in charge of philly.com, the Inquirer and the Daily News.

And so the question is how we should react to this change. We could be happy that he has gone public, and we could accept his presence and his aid, gratefully, because cities like Camden and institutions like the Inquirer and regions like ours can use all the help we can get. If that’s the case, what’s a little naughty language among friends? But those who feel run over by the Norcross machine would probably express a different desire: to see their assailant get the same rough treatment he’s so infamous for delivering; to see the rich and powerful George Norcross III finally, as he himself might put it, get fucked.