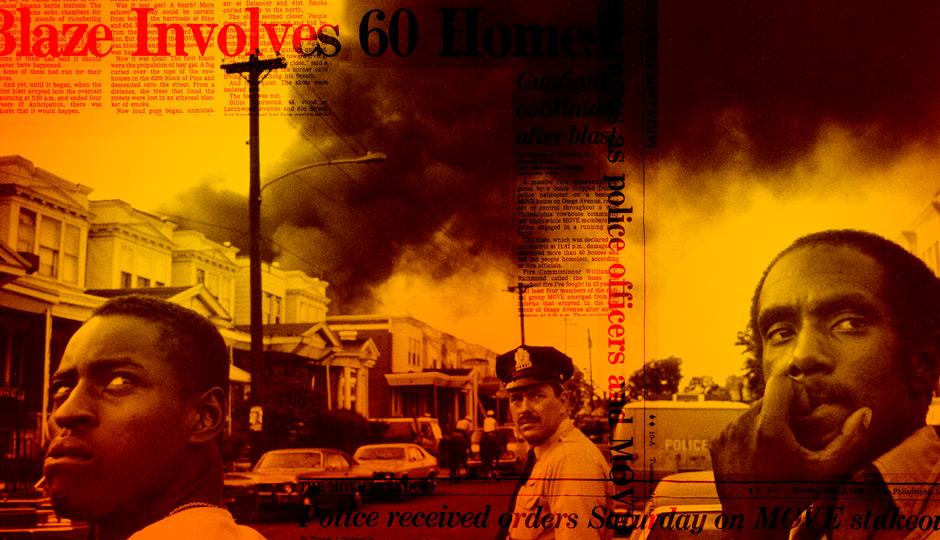

The MOVE Bombing: An Oral History

Decades later, the people who were there that day tell the still-unbelievable story.

IT WAS A standoff years in the making at 6221 Osage Avenue — the headquarters of a group called MOVE. The neighbors were fed up. The cops had warrants. And the members of the MOVE organization had barricaded themselves inside. Their demand? Justice for nine MOVE members incarcerated — wrongly, some say — for the 1978 murder of Officer James Ramp. On May 13, 1985, shots rang out. Bystanders — including a young Michael Nutter — took cover.

And then, as the sun began to set, a police helicopter flew in and released a bag filled with explosives onto the headquarters, making ours the only American city ever to drop a bomb on its own citizens. At the end of the day, 61 houses blazed, and 11 people — five of them children — died, the nightmarish images forever burned into Philadelphia’s consciousness. Here, the people who lived through it tell the extraordinary story of the MOVE bombing.

Ramona Africa, MOVE spokesperson and the sole adult survivor of the 1985 fire: MOVE was formed in 1972 by John Africa. He gave us one common belief, in the all-importance of life. We had peaceful demonstrations: the Zoo, the circus, furriers, Dow, du Pont, and unsafe boarding homes for the elderly.

Andino R. Ward, father of Birdie Africa (aka Michael Moses Ward, who died in 2013), the sole child survivor of the 1985 fire: One day in the early ’70s, my wife Rhonda had a friend who was telling her about this group, MOVE. At this point, Rhonda and I were separated. Not long thereafter, I went to her mom’s house to pick up Mike. Her mom said they no longer lived there, she’s with MOVE. I went to the Powelton MOVE house, almost went to blows with John Africa. Then a guy came with a hatchet, so I got out of there. Later, Rhonda told me that her new family was MOVE, that John Africa was Mike’s father, that I could forget any involvement.

Michael Nutter, mayor of Philadelphia from 2008 through 2016: In the late ’70s, there were various public activities involving MOVE. I was studying at Penn, and really only generally aware of them.

James Berghaier, retired Philly police officer: I’d see them acting up in the courtroom, but I didn’t give them any credibility.

Ramona Africa: The cops would come out and tell us we had to break down and go away. MOVE would not accept that.

Tigre Hill, director of The Barrel of a Gun, a documentary about Mumia Abu-Jamal: John Africa came to be at a time of all the cults. Tim Leary. Jim Jones. John Africa wanted to blow up capitals. They were anti-cop, anti-government, anti-technology.

Sam Katz, three-time mayoral candidate: These folks made life in the neighborhood intolerable — they were disruptive of civil life to the extreme.

Angel Ortiz, former City Councilman: This was an intolerant time. If you were different, you were pursued. The MOVE members fit into that pattern. They were loud. But I don’t believe they were plotting subversive action against the state.

Ramona Africa: The government couldn’t explain their position, didn’t want to hear us. That’s when the beatings and unjust jailings started. MOVE men and women — pregnant women — were beat.

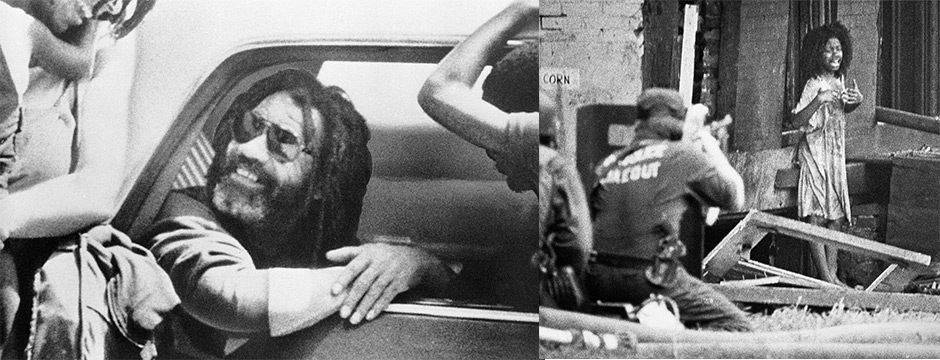

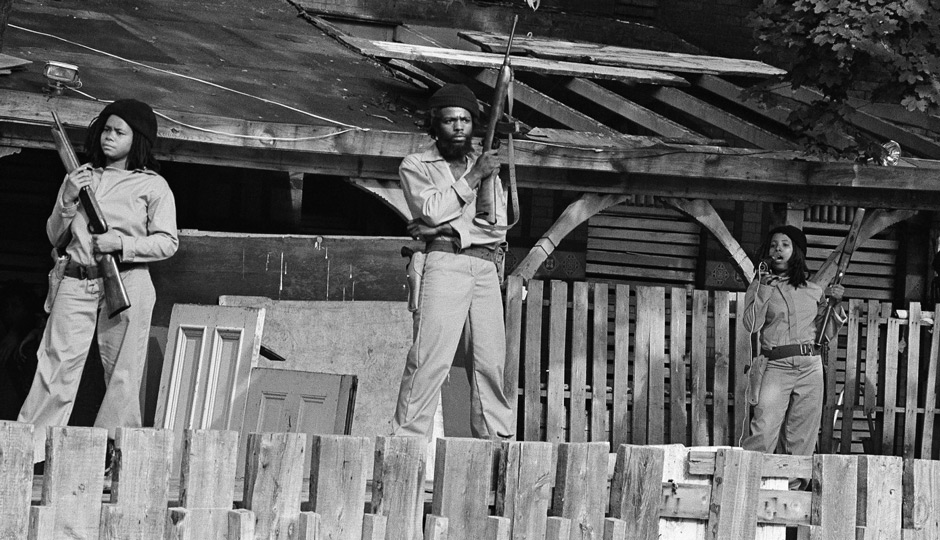

James Berghaier: And then there was the guns-on-the-porch incident.

Ramona Africa: We are not a violent people. We are uncompromisingly opposed to violence. But we do believe in self-defense. You’re violent if you don’t defend, because then you’re endorsing violence.

Andino Ward: In the mid-’70s, I went to the Powelton house. I tried to initiate conversation, and somebody shot at me. I took off running. Wouldn’t see my son for another 10 years.

Tigre Hill: Today you have this revisionist history of this peaceful group in West Philly. They were not peaceful.

Ramona Africa: In May of ’77, we took a stand after MOVE people were beat bloody. You come at us? We’re coming back at you. We took to a platform built in front of our house, and we displayed weapons.

James Berghaier: We got called in. The commissioner said, “I don’t want any crazy shootings. Find good positions. If shooting starts, do you have a problem taking them out?” I said no.

Charles “Tommy” Mellor, retired Philly police officer: I never heard of MOVE until ’77. When I saw them brandishing their weapons, I was taken aback. Them standing out there with automatic weapons, and no one was doing anything about it.

James Berghaier: From 1977 to 1978, 24 hours a day, we sat outside and listened to the rhetoric. If they came out, we were to apprehend.

Ramona Africa: Our main demand was that the members in jail for riot and weapons be released. Mayor Rizzo said he didn’t negotiate with terrorists, so we stood our ground.

Frank Rizzo Jr., son of then-mayor Frank Rizzo: My father made the decision to evict them with a court order.

Ramona Africa: They turned off our water, didn’t pick up our trash. Then on August 1st, the city said they wanted every MOVE person out, we had to give up our home, and we said no. It wasn’t about the house. They wanted to get rid of — to murder — MOVE.

William Richmond, former Philadelphia fire commissioner: In ’78, I was deputy chief in charge of research and planning, and we were involved in the planning process for that episode. I went on-site and looked at the geography, saw what problems we might encounter.

Tigre Hill: In 1978, I was 10. My mom and I drove to the compound to stop and look. There were TV trucks. Police barricades. The next day was the shoot-out.

Ramona Africa: In the middle of the night, hundreds of cops marched out with the fire department. Not to arrest, but to kill.

James Berghaier: Bullshit. I didn’t go out there to kill. I went in to put in my eight hours and was there to call their bluff.

William Richmond: We set up deluge guns to knock down the wooden slats they had over the windows.

Ramona Africa: They pumped almost six feet of water into that basement, knowing there were men and women and babies and dogs in there.

James Berghaier: After Monsignor Devlin wasn’t able to talk them into coming out, the fire department started the deluge gun. I thought they were going to come out, I really did. I didn’t think they were that devoted. The worst thing you can do is underestimate your adversary.

Tommy Mellor: We broke down the fence surrounding the house. I was the third person through the front door. We eventually got to the basement with the tear gas.

James Berghaier: Pretty soon, gunfire erupts. I fired two or three rounds.

Tommy Mellor: Bullets were flying, hitting pipes. We were in water up to our waist, and there were rats and feces. It was a bad place to be.

William Richmond: When the shooting started, our firefighters were in the wrong place. We had a number hit. Whatever plan was in place didn’t flow.

Tommy Mellor: I couldn’t tell what was going on.

James Berghaier: I can’t say I saw a MOVE member shoot, and I can’t tell you I saw a cop shoot. But I did see the result of it. Officer Ramp was dead. After the shooting, the women came out with the kids. That was the end of it. They knocked the house down.

Ramona Africa: The cops emptied their guns and then emptied them again. James Ramp was on street level facing MOVE, and he was shot by a bullet traveling downward. Obviously, somebody above him killed him.

Tigre Hill: From all of the documentation I’ve seen, it’s clear that Ramp was killed by MOVE.

Angel Ortiz: Did the MOVE members shoot Ramp? This has never been fully answered. The MOVE compound was razed without proper forensic analysis.

Ramona Africa: A team came to demolish MOVE headquarters. They were accusing my family of killing a cop. That makes it the scene of a crime. Why destroy the evidence?

Frank Rizzo Jr.: A lot of people feel there was a police cover-up. Friendly fire. The person who killed Ramp was in the basement of that house. And the person who killed him, those people are in jail.

On August 4, 1981, nine MOVE members were sent to prison for the murder of Officer Ramp. In the years that followed, during which time MOVE supporter Mumia Abu-Jamal was sentenced to death for the murder of Officer Daniel Faulkner, MOVE relocated its headquarters to 6221 Osage Avenue, and continued to fight for the MOVE 9, becoming even more of a thorn in the side of the neighbors, the city, and the new mayor, Wilson Goode.

Seth Williams, district attorney from 2010 through 2017: In the early ’80s, I was in high school at Central. MOVE bought a home on Osage. My house was just around the corner. I played basketball with the MOVE guys. There was no political talk. Just the trash-talking that goes on at pickup games in West Philly.

Angel Ortiz: When I joined Council in 1984, MOVE was still having problems. Neighbors complained about hygiene and loud music.

Charles Diamond, former priest at St. Carthage: The church was a half-block from Osage. They were constantly blaring messages. My congregants were hearing people running over their roofs at night.

Ramona Africa: We had met with Wilson Goode when he was managing director. But when Wilson became mayor, we couldn’t get near him. He wasn’t going to do anything for us. So we set up our microphone and started boarding up our home.

Theodore Price, former resident of neighboring 6250 Pine Street: I didn’t have too much confrontation with them. I worked nights. But I knew people who had lots of problems with them.

Ed Rendell, former mayor and then–district attorney of Philadelphia: The neighbors were complaining about everything from loud noise to a horrible smell. All sorts of nuisance complaints.

Seth Williams: By the spring of ’85, they’re on bullhorns shouting obscenities all the time. People were fed up. The public forced the hand of the managing director [Leo Brooks] and police to do something.

Ramona Africa: The cops claimed we were bad neighbors. Since when has this government shown any interest in black people complaining about black people?

Ed Rendell: The police came to me and said, “What do we got here?” And I said, “You might advise the neighbors to come file a private criminal complaint.” But there were no felonies, probably nothing to get an arrest warrant on.

Angel Ortiz: You could see it developing if you had any sense. It was a police state. But I thought it could be handled.

James Berghaier: With Goode being the mayor, I thought the chances of negotiations would be greater. I thought it would get resolved.

Ed Rendell: Then weapons were brandished, I believe. And tied with the threats — it became actionable. Not major, but actionable.

Frank Powell, retired police lieutenant: Late April of ’85, we got word that the city wanted them out, to come up with a plan. I was the head of the bomb squad back then. So we got together — the bomb squad, the firearms training unit and the tactical division. The plan was to go to the homes adjacent to the house — remember, this was a rowhouse — and blow small holes in the wall using a charge and inject tear gas.

Ed Rendell: I guess maybe 10 days before the fire, I went out there and talked to one or two members over the fence. I said, “Look, guys, you can’t go on like this. No good can come of this. Why don’t you just surrender?” They were very respectful, but they basically said no. And I didn’t have any further contact.

Frank Powell: MOVE had built a bunker on the roof of the house, and it was clearly a problem. It covered any operations on Osage. Police Commissioner Sambor asked me if I could get up on the roof and put a charge on the bunker. But I couldn’t. I’d be exposed to shooters in the bunker.

Bob Brady, former Congressman and then-deputy mayor for labor: I was in Goode’s office. There were a lot of people there. Richmond. Sambor. All these military men giving advice. I thought it would be a good idea if we got a boom crane to knock that bunker off. But somebody above my pay scale decided against it.

Ed Rendell: The police came to me in Goode’s office and showed me aerial photographs. There were weapons and big cans of oil on the roof. I authorized arrest and search warrants.

Wilson Goode, in testimony before the MOVE Commission, October 15, 1985: I directed [police commissioner Gregore Sambor] to be in charge of [a] … plan that would enable us to make arrests of such MOVE members as the D.A. was able to provide warrants for … the protection of police officers and firefighters and occupants of the house was paramount. … We did not want persons involved who may have a hot temper, who may emotionally have been attached to 1978. … What I said to him was … “I’m the mayor, and I must rely upon you to go and do a proper kind of plan.”

Gregore Sambor, former police commissioner, in testimony to the MOVE Commission, October 17, 1985: We had lessons from sad experience. In the spring of 1977, we had hoped that armed threats would disappear if pacified. By the fall of that year, we had thought that an indefinite state of siege would starve MOVE into submission. By August of 1978, we hoped that an overpowering police presence … would intimidate MOVE to peaceful surrender. The plan for May 13th was the most conservative, controlled, disciplined and safe operation that we could devise based upon these lessons.

William Richmond: Late Friday, I get a call that there was a meeting at the police administration building on Saturday morning. At the meeting, we were told that Sambor would make a pronouncement by bullhorn for MOVE to exit the house. If they didn’t exit, we’d start the squirts and throw water at quite a volume to neutralize the bunkers. Then the police would get the tear gas in. But we hadn’t been out there. The planning was terrible.

James Berghaier: We were going to breach walls in the basement and second floors and use tear gas, leaving the first floor as an escape for MOVE people. And I think, I’m okay with this.

Theodore Price: On Sunday, May 12th, 1985, the police told us that we had to go somewhere and stay. I went to a hotel on Baltimore Avenue.

Ramona Africa: We knew something big was about to happen. Police told people to go out and visit family, that they could come back the next night. Boy, were they wrong.

Michael Nutter: In 1985, I was Councilman Ortiz’s chief of staff. He asked me to look into the situation that Sunday. There were police barricades, news vans, and a general sense of tension in the air. I talked through a screen door with Ramona Africa. She expressed that the family was upset about the members locked up, and they were prepared to take whatever actions necessary to try to make their release happen. Soon, there was increasing presence by the police, specialized officers, SWAT teams. I was out there most of the night.

Tommy Mellor: We get out to the house at 4 or 5 a.m on Monday. It was very quiet. Dark. Eerie. I was carrying a tear gas machine.

William Richmond: I rode out on the squirt truck. This was the first time I had seen the bunker or Osage. We positioned on 62nd Street. That’s when we saw the trees in our way, and I thought, The squirts aren’t going to reach.

Michael Nutter: Police presence significantly increased again. The power had been turned off. And then the commissioner made an announcement that the folks should come out of the house.

William Richmond: I’ll never forget it. “This is America …” he started.

Ramona Africa: He said, “Attention, MOVE. This is America. You have to abide by the laws and rules of America.”

Frank Powell: Then one of them gets on the loudspeaker and calls the commissioner a motherfucker.

Michael Nutter: At some point, what sounded like gunfire broke out. People were running for cover.

William Richmond: Once the shooting started, we turned on the squirts, but they were too far. We couldn’t neutralize those bunkers.

Tommy Mellor: What major city lets people build a bunker on their roof? You try to build a fence and L&I will shut you down.

William Richmond: The bunkers were critical. They overlooked everything. High ground, in military parlance.

Ramona Africa: Firefighters are sworn to protect life, but they were the first phase of the attack. The water was pouring into the house, and then we heard that the police were going to try to use tear gas.

James Berghaier: We used the charge in the wall next door, and Tommy Mellor started to put the pipe through but hit something.

Tommy Mellor: We didn’t realize how well-fortified the house was. I could barely make a dent in it to get the tear gas in.

James Berghaier: They had walls inside of walls. But we did get through and get gas on for a bit.

Marc Lamont Hill, Columbia University professor and former Fox News correspondent: I was only seven, living in Germantown. During the day, as things developed, the teachers were talking about it. I remember one was crying. They were upset.

Michael Moses Ward, formerly Birdie Africa, in 1985 testimony before the MOVE Commission: We was in the cellar for a while … and tear gas started coming in and we got the blankets. They was wet. And then we put them over our heads and started laying down.

Ramona Africa: They were shooting. They knew there was children. They had arrest warrants, yes, but we hadn’t been convicted of anything. And what they claimed to be arresting us for was not capital offenses. They had artillery of war. M16s. Sidearms. Sniper rifles with silencers — the weapon of an assassin.

James Berghaier: The bomb guys were using some sort of charge to try to breach the wall. We attempted to get back into the [neighboring] house, but the way it was explained to me, MOVE violated the integrity of the house by knocking down joists. The first floor of the house we had been in collapsed.

Frank Rizzo Jr.: My father never had much respect for Sambor. People thought my dad was excessive. But Sambor ran around in fatigues. Dad heard that they were planning to drop an explosive.

Frank Powell: Around 4 or 5 p.m., they call me into a meeting. Sambor asks if we could use a helicopter to blow the bunker off. I don’t know, I say. I never dropped a bomb out of a helicopter. What happens if they shoot the helicopter down and it lands on a house? What happens if I miss?

James Berghaier: We hear that a helicopter is going to drop a bomb. We’re supposed to take a defensive position. I blew it off: You’re not going to drop a bomb.

Tommy Mellor: They had pulled us out of the house, so I went to Cobbs Creek Parkway. Ducking bullets all day tires you out. I went to sleep in the dirt. Somebody woke me up, and I heard they were going to throw a device to knock the bunker off. Of all the strange things going on then, it didn’t seem strange.

Gregore Sambor, in testimony: The use of the device itself gives me the least pause. It was selected as a conservative and safe approach to what I perceived as a tactical necessity. I was assured that the device would not harm the occupants. What has imprinted that device on the mind of the city is, in fact, the method of delivery. If it had been carried or thrown into position or if it had been dropped from a crane, the perception of that action would be quite different.

William Richmond: So the decision was made to take a helicopter, and use a satchel charge — that’s the term for explosives in a gym bag. The helicopter made two or three passes with Frank Powell strapped in.

Frank Rizzo Jr.: I’ll never forget it. My father was in the family room, watching it all on TV. When he saw the state police helicopter, all the intelligence he had started coming together, and he said, “Son, they’re going to drop a bomb on this headquarters.”

Frank Powell: As soon as I dropped the satchel, the pilot got the hell out. The rotor wash blew it across the roof. I said, “Oh shit!” And then it went off. There was a football-shaped hole. It missed the bunker.

Michael Ward, in testimony: That is when the big bomb went off. It shook the whole house up.

William Richmond: Frank dropped it, which took a lot of moxie. The concussion knocked out windows of nearby homes. Debris went everywhere. Minutes later, someone said to me there was a fire on the roof. These things start small and build up over time.

Ed Rendell: When I heard that they used an incendiary device on the roof, I was amazed, because you could clearly see drums of oil up there. And it would seem to me to have been lunacy under those circumstances to drop an incendiary device. But they did. And as the afternoon rolled on and the fire started, it became almost a holocaust.

Frank Rizzo Jr.: When my father saw the fire department shut the water off, he couldn’t believe that anyone in the U.S. would use fire to force people from a building.

William Richmond: Originally, the police wanted to access the property via the hole in the roof. We couldn’t leave the squirts on, because we’d wash off police attempting to breach. And the squirts caused a tremendous amount of smoke — the fear was that MOVE members would exit shooting from different locations. There was a managing director’s directive in place. One commander in place: the police commissioner. We were under authority of police.

James Berghaier: There’s so much fire and smoke. We can’t tell what’s gunshots and what’s windows popping. And we hear over the radio that someone is coming out.

Tommy Mellor: And then Ramona comes out, surrounded by smoke. And Birdie comes out next.

James Berghaier: It was like fantasy. Like he came out of fire. He was barefoot. Ramona tried to pick him up but lost her grip. He landed on his head … I scooped him up. And Tommy took Ramona into custody.

Tommy Mellor: By this time, the fire had already spread to other houses.

Angel Ortiz: I was coming out the back of the Art Museum with Ed Rendell and my wife. We saw the plume of smoke, and Ed and I looked at each other. It was one hell of a fire.

Ed Rendell: Later that night was the spring Democratic dinner over at the Franklin Plaza, and we watched the houses in flames on one of the little TVs in the bar.

Seth Williams: My friends and I watched the fire in disbelief. It went from a minor tragedy to a catastrophic event. Eleven of my classmates lost their homes.

Tigre Hill: I came home from Archbishop Carroll. I lived — and still live — in Wynnefield. It was on TV, and from my house, which is a distance away, I could see the smoke. My mother and I, we were just so stunned.

Theodore Price: We had no idea what was going on, so we checked out of our hotel on Monday. When we got to the street, there was a whole lot of action. And after they dropped it, the fire starts trickling to each house. Boom, boom, boom!

Sam Katz: I was landing in an airplane in South Philly, and the sky was bright orange. I had no idea what it was. But it was a remarkable scene from up there. Then I was on the ground in my car, with KYW on. The whole thing just careened completely out of control.

Theodore Price: It burnt 61 houses. It looked like a war zone. My house was completely destroyed. I had just put in new siding and picture windows. I lived in that house since 1957. It was bought and paid for.

Wilson Goode, in a press conference that night: I stand fully accountable for the action that took place tonight. I will not try to place any blame on any one of my subordinates. I was aware of what was going on, and therefore, I support them in terms of their decisions. And therefore, the people of the city will have to judge the mayor, in fact, of what happened.

Gregore Sambor, in testimony: I remain convinced that any approach on May 13th would have presented an immediate and deadly danger. … It remains a fact that if MOVE members had simply come out of the building, they would be alive today. But they announced that morning that they would never surrender and that they would kill as many of us as they could.

Marc Lamont Hill: I’ve talked to Goode. He regrets his actions. I would argue that it’s the biggest regret he has in his life. It haunts him. I wouldn’t be surprised if his move to the clergy was prompted by his deep sense of regret and guilt.

Sam Katz: I don’t want to point the finger at who should be punished, but there was a moral breakdown here, both in the act and the aftermath. I think it affected Goode profoundly.

Wilson Goode, in a 2004 interview with Philadelphia magazine: In the whole scheme of things, MOVE was a bad day. It was a really bad day.

On March 6, 1986, the 11-member Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission — or MOVE Commission — issued a report condemning city officials, stating: “Dropping a bomb on an occupied rowhouse was unconscionable.” No criminal charges were filed against anyone in city government. Wilson Goode was reelected to a second term.

A burned Ramona Africa served seven years in prison for charges relating to the May 13th confrontation. Following her 1992 release, she won a civil case against the city for $500,000. Michael Ward was reunited with his father, Andino Ward, and later won a $1.5 million judgment against the city.

The 250 residents who lost their homes had yet another saga to endure: rebuilding, a process plagued by patronage, politics and incompetence. It continues to this day.

Many of the police officers involved were profoundly affected by their experience. James Berghaier quickly left the force due to post-traumatic stress disorder. Another officer committed suicide.