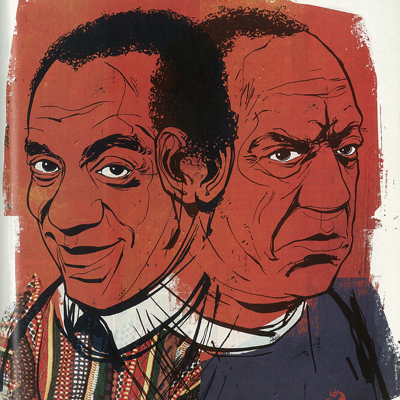

Dr. Huxtable & Mr. Hyde

Who is Bill Cosby? What's happened to the man who taught us to laugh at ourselves — and what do we do with him now?

“He did a lot of good works behind which he could stash his crimes of excess.” — Tamara Green

Our stories must be told a certain way. That is why Bill Cosby is holed up, on a hot late-April afternoon, in a convention center in Greenwood, Mississippi. There are maybe 300 folks, overwhelmingly black, in a hall that seats several thousand, where Cosby has come to “call out” to the community, to talk direct and tough. To get the folks to believe that if they want the mess of their lives to change, they’ve got to do it themselves, and stop thinking and acting like victims. He is prancing back and forth in sweatpants and a pullover, diving into the sparse audience to ask questions and make demands, but also flirting with that wide elastic face of his — of course, the crowd is easily his.

“Those of you who are living with someone on drugs,” he tells them, “you don’t even hide your stuff anymore, because they know where to look.” Cosby mugs the foolish ignorance — “How did she know to look in the washing machine for the money?” — and gets titters of recognition, but he isn’t fooling around.

After the call-out, Cosby sits in a private room, alone with one woman. He needs her to tell her story for a second call-out, coming up in an hour. Unita Blackwell was born to sharecroppers during the Depression, not far from here. In her 30s, she plunged into the civil rights movement, and went on to become a small-town mayor and something of a local can-do legend; her memoir is coming out. Yet time and age — Unita’s 73 — have clouded the story of her youth. So now Cosby keeps asking questions, beginning with her early childhood:

“Did you work in the fields?”

“I didn’t really until I got older.”

“How old?”

“Oh, I was probably around eight, something like that.”

“ … You said there were two of you.”

“My sister … ”

“Who was your sister?”

It goes on like this, Cosby digging out the nominal facts, building to what he’s really looking for:

“Now, your mother did what?”

“She would work in the fields.”

“And raise the children … so you were eight years old, working in the fields, and — ”

“That’s nothin’ new,” Unita reminds Bill Cosby.

“That’s not what I’m talking about!” Cosby tells her. “Where I’m going with this, I’m looking at schooling. … Did your mother read to you? Did your mother give you mathematics? Who do you remember giving you something pertaining to education?”

“I had an auntie,” Unita remembers vaguely. “Her name was Rosie. Aunt Rosie. The Bible … We didn’t have a lot of books. We were very poor.”

She’s on the brink — this is what he’s looking for. Unita doesn’t need his help; she pulled out of poverty and ignorance a long time ago. But that’s exactly the point — for the next call-out, Cosby wants Unita up on stage with some others to tell that story, to tell her story the right way, how she took the little help given her and got somewhere herself.

For the past two years, Bill Cosby, 68 years old, has been trying to fix people’s stories, all over the country. He’s dropped in on cities, mostly — Detroit, Newark, Baltimore, Milwaukee — staging these call-outs. Greenwood is a Delta town of 18,000 beset by poverty, drugs and despair. It’s a place where a big fertile yard is easy to come by, but not the wherewithal, or maybe the ambition, to do better than the shotgun shack falling down in the middle of it. His message is no different here. He’s trying to get America’s underclass to take responsibility, to act. Actually, given the sorry, and declining, state of lower-class blacks, it’s much more than that: Bill Cosby is trying to save them.

That’s why he talks so firm, here in Greenwood, on giving in to a scourge like drugs: “He stole my car — that’s my child. He punched me in the face when I told him no more money. He pushed me down the steps. And you’re going to protect the drug dealer. … You are not making sense. … You got to think, people.”

All told, Cosby will harangue and plead and hope for some six hours today before heading back down an 80-mile yellow tongue of highway that splits deep woods, down to Jackson and his Gulfstream jet. To Cosby, this is a mission, and he is giving the performances of his life (upcoming call-outs: D.C. and Kansas City and L.A.) in a bold attempt to grab the bootstraps of black America and give them a big, everlasting yank.

But there’s something else, along with the plight of poor people, dogging Bill Cosby. His lawyers have gotten it pushed to the back burner, down to a simmer, and maybe it will amount to nothing, yet there is also the possibility that it will bubble up to destroy him. A young Canadian woman he met in Philadelphia through Temple University is accusing him of drugging her and then, when she was in a near-comatose state, molesting her. It went nowhere legally — the woman, Andrea Constand, waited a year before going to police, it boiled down to a he said/she said (Cosby claimed the sex was consensual, according to ABC News), and the police dropped the case for lack of evidence. But Constand filed a civil complaint in federal court in Philly last year, suing for an unspecified amount of money over $150,000. It is still Cosby’s no against her yes, except for one difference: Thirteen women are waiting to be deposed in the suit; in a court filing, Constand’s lawyer says that all of them — with nothing to gain, with no payout waiting, with their own statutes of limitations run out — have stories about Bill Cosby as well, and some of them will claim a similar drug-and-fondling M.O.

These accusations are about as far removed from the character of Heathcliff Huxtable — that’s Bill, right? — as we could imagine. They are equally far removed from Bill Cosby’s mission to drive poor blacks to a righteous, hardworking path. And as Cosby’s lawyers string out the suit, filing motions, keeping it in limbo, with those witnesses largely quiet and nothing substantiated, it remains — even 14 strong — nothing more than allegations, about which Bill Cosby has nothing to say.

But it is not that simple. It’s a crazy game Americans in particular seem to play, the way we need to believe desperately in our heroes — we want Bill Cosby to be as sweet as Cliff, to be as noble as his desire to lift up his people. His career has been predicated on just that: our sense of him. Cosby the master storyteller — at his best, on a level with Twain — has always used himself, our connection to his slow charm and easy-to-lap-up messages. Cosby, playing himself, is his own best character. But if he would turn out to be harboring dark personal secrets. Or worse. …

Bill Cosby won’t talk about that. Or anything, when the subject is him. But he’s doing plenty of talking, and getting to the truth of other people’s stories. That’s why he came to the godforsaken Delta. That’s why, between call-outs, he kept right on working, grilling Unita Blackwell, pushing to the heart: how she pulled herself up from nothing. Because that’s the story all of them must hear. The only story that will inspire them to make their lives better.

Yet given Cosby’s palpable need to come to places like Greenwood, Mississippi, you start to wonder about all this, about what he’s up to. You start to wonder why he’s so driven to spread the word to poor blacks, to tell them what they must do. You start to wonder if there is only one life he’s really trying to save, a little closer to home.

* * *

The Story That Andrea Constand Tells

She met Bill Cosby in late 2002 when she was director of operations for Temple’s women’s basketball. He became a friend and mentor. In January 2004, Cosby invited Constand to his home in Elkins Park. She went there at about 9 p.m. Constand wanted to change careers and told Cosby she felt stressed. Cosby offered her three blue pills — herbal medication, he said, that would help her relax. She took the pills. Soon, Constand’s knees began to shake; she felt dizzy and weak. She told Cosby she did not feel well. Cosby led her to a sofa, then positioned himself behind her, touched her breasts, rubbed his penis against her hand, and digitally penetrated her. Constand was semiconscious throughout. She could not give consent to these acts, and she did not. She lost consciousness, and woke around 4 a.m. She felt raw in and around her vagina. Her clothes and undergarments were in disarray. Bill Cosby greeted her in his bathrobe. Andrea Constand left his house by herself.

THE CALL-OUT THAT got everyone’s attention was at Washington’s Constitution Hall on May 17, 2004, when Bill Cosby received an award for philanthropy at an event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, and made some remarks. He said that the poor were “not holding up their end of the deal.” He said that parents “cry when their son is standing there in an orange [prison jump] suit,” but the reason he’s there in the first place is lousy parenting. “Where were you when he was two? Where were you when he was 12? Where were you when he was 18, and how come you didn’t know that he had a pistol? And where is his father?”

Tough stuff, but Cosby was just warming up: He assailed black youths for putting their clothes on backwards, girls for “needles and things” going through their bodies. Giving children names like “Shaniqua, Taliqua and Muhammad and all that crap” also rankled him, as did current street lingo. There was more, making the same point: Bill Cosby was fed up and was not going to take it anymore.

Reaction was fierce, and ran the gamut: Cosby, attacking his own people from the safe perch of vast wealth, was cruel and way off the mark; or, he had the cojones to go right up the gut of what desperately needed to be said. Washington, though, wasn’t Cosby’s first call-out. No, like a play debuting in the hinterlands, he had tried out his spiel first, a couple months earlier, in Philadelphia. Then-Inquirer columnist Lucia Herndon broke the story, something that still unnerves her.

Herndon, like a lot of black girls and boys in America, grew up on Bill Cosby. Grew up loving him. She bought every one of his records. His role in I Spy — he was so handsome, so charming and daring — sent her over the edge. When Cosby came to her town, Des Moines, to perform, Lucia and her friends went to every hotel looking for him; when they miraculously found him, sitting in a car, she told Cosby she was writing a piece for the school newspaper about him, and asked if he would sign her yearbook. He did. It was 1968.

In March 2004, Herndon was asked to make a few remarks at the semiannual Year of the Child production at Deliverance Evangelistic Church in North Philadelphia — a Sunday afternoon celebrating extracurricular achievement. Actor Clifton Davis would sing. School superintendent Paul Vallas would speak. So would school reform commission head Jim Nevels. And weatherman Hurricane Schwartz. And Bill Cosby.

Hurricane Schwartz said that Philadelphia is a good place for a hardworking artist to fulfill his dream; Herndon spoke about the art of the written word. Bill Cosby had a different theme.

“We have become afraid of our own children,” he told the budding artists and their parents. “Afraid that the child will not like us or love us. This is not parenting. … Where did we lose it? When did we find it easier to give a kid a video game than to talk to our children?” Cosby also made “a call to all fathers. Men need to step up and be a parent to the children they make.” And he hit the idea of family literacy, remembering that his mother read to him and his brothers at night. “She didn’t give us a damn remote.”

Herndon and Hurricane Schwartz turned to each other, wide-eyed. What was he doing? Why here, at this event, with all these children, some of them as young as five? Cosby didn’t even mention them, the performers or their families, even though a pat on the back was supposed to be the point of the event.

Or so Herndon thought. And she said so in an Inquirer column that ran 10 days later — not disagreeing with Cosby’s points, but declaring that he picked the wrong time and place. Why was he lecturing an audience of parents that did get it?

A few days later, Herndon got a phone call. It was Bill Cosby. He was angry. She had it wrong, he said. Did she misquote him? No. What was wrong? Her viewpoint.

Well, she was a columnist, and entitled to express —

She was wrong about the audience. A big place, almost 3,000 folks, and some of them there did need to hear the message.

Okay, she didn’t poll the audience to see if they were all related to a young performer, but she was sticking to her perspective, that it was the wrong venue to —

What church did she go to? Maybe her problem was that she didn’t understand speaking from the pulpit in a black church.

So he was questioning her … blackness? What did he want her to say?

That she was wrong. In print. There were families there that needed to hear what he was saying.

No, she wasn’t going to do that.

But she was wrong.

It went around and around like that for some 40 minutes. Herndon wouldn’t budge. Cosby wrote a letter to the Inquirer, which was printed. Then Herndon got a letter from his lawyers, threatening the paper with legal action. Because, as she sees it, she disagreed with Bill Cosby. The lawsuit never materialized, but “Mom has fallen out of love with Bill Cosby,” her daughter teased her.

Cosby keeps close tabs on anything written about him. His head PR guy in L.A., quite interested in how this article was going, called me on a Saturday afternoon. It wasn’t just to chitchat. I had interviewed Lana Felton-Ghee, who produced that Year of the Child event, a couple days earlier. She called Cosby. And Cosby, still angry at Herndon two years later, wanted me to know, his PR guy said, that the Inquirer and Daily News have had it in for Cosby, their coverage is completely biased, and that I must read everything they’ve ever written about him in order to grasp that.

Though the fairness of our local newspapers is not really the point. It’s that disagreeing with Bill Cosby means you are wrong; to ward that off, he works very hard trying to get a writer on his side. Cosby dodges interviews like civil suits, but that doesn’t stop him from having his doorman in New York call me and leave messages with the élan of an Italian tenor — “This is FABIO!” — that Mr. Cosby wants to send me faxes: glowing letters of appreciation for this or that, or glowing reviews of his call-outs around the country. All told, four assistants have called, sending me information. Which is not especially unusual, for those who have four assistants. Nor is it unusual for someone to decline to talk to a writer. But the barrage of positive information, coupled with virtual silence from the man himself, is — not to put too fine a point on it — transparently controlling and paranoid.

***

The Story That Tamara Green Tells

Back in the ’70s, before Green became a lawyer, Cosby hired her to help him open a club in L.A. A week into the job, she felt sick, and called Cosby at Figero, a restaurant he owned, to say she was leaving for home. He invited her to the restaurant for lunch — it might make her feel better. She went. Cosby asked if she wanted some Contac, then handed her two gray-and-red capsules. She took them. Thirty minutes later, she felt stoned. Cosby offered to drive her home. Inside her apartment, he tried to undress her. She fought him. He kissed her and kept pulling at her clothes. “You’re going to have to kill me,” she screamed. He let her go. Cosby dropped two $100 bills on an end table and left. Green never returned to her job.

BILL COSBY’S LOUDEST critic these days is Michael Eric Dyson, the Penn prof, writer-at-large for this magazine, and author of Is Bill Cosby Right?, which takes on the substance of Cosby’s call-outs. To Dyson, Cosby’s been on a “blame the poor tour” the past two years; certainly, Dyson argues, Cosby is well aware of institutional racism, of trends in the economy that have sucked away high-pay, low-skill jobs, but he’d rather tell America’s ghetto that the reason their lives are a mess is them.

As Dyson tells it, he ran into Cosby one night this spring in New York. He’d just gone to the premiere of Spike Lee’s movie Inside Man, at the Ziegfeld theater; Dyson and his wife were walking to one of the related parties when she spied Ed Lewis, head of Essence magazine, through the plate-glass window of a restaurant. Both Dysons have written for Essence, so they went up to the window and waved to Ed and his wife.

Then it struck Michael that the woman sitting next to Lewis’s wife was Camille Cosby, Bill’s wife, someone Dyson had never met, but of course he recognized “a world-famous woman, with her beauty and her distinguished look.” So he waved to her, too — why not? Right about then, it dawned on Dyson that if Camille Cosby was sitting there …

Bill would be, too. Sure enough, with his back to the window. Now Cosby slowly turned to the Dysons, but only partway, so that he could, maybe, see them out of the corner of his eye. Then he raised his right arm above his head, and his middle finger shot up in salute.

Dyson blew kisses to everyone (though Cosby’s back was turned again) and mouthed, “Thank you!”

The next morning, as Dyson took the train from New York back down to Philly, the porter told him that Bill Cosby was on board as well; oh, this was too good to pass up. Dyson went to him and put out his hand; Cosby shook it. Then Dyson sat down. Cosby sort of apologized by saying the night before had been Camille’s 62nd birthday, and when they told him who it was outside the restaurant … Bad moment. Then they talked. For better than an hour, on the train, then in 30th Street Station, Cosby bore right in on Dyson, an inch from his face, to tell him how wrong he was.

Cosby — or Cosby’s people — had done his homework. He knew that Dyson had been a 14-year-old gang member in Detroit with Coca-Cola-thick glasses, but that somebody had started watching out for him, telling Dyson to get away from the gang — in Cosby parlance, a mentor had “put a body on you.” “And that minister,” Cosby told Dyson, an inch from his nose at 30th Street, “you wanted to be like him. They put a body on you!” So Dyson, Cosby was saying, had gotten help, and responded to the help, and that must be the center of his story. A story of achievement, of overcoming. Forget this liberal victim crap that Dyson is stuck on.

On April 1st, Cosby and Dyson met up again in New Orleans. They both spoke at a march there — along with Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton and other notables — to rally support for residents who’d been disenfranchised from voting in an upcoming mayoral election because they’d been relocated in the aftermath of Katrina. Except that Cosby had a different message: “I want to talk about before Katrina.” And he went on to point out that before the hurricane, New Orleans had the highest murder rate in the United States, 12- and 13-year-old girls were regularly becoming pregnant, and so forth. Back to the problem being … them. Cosby’s stump speech.

At the march, Cosby told Dyson why he wouldn’t come on his radio show or debate him publicly. “I will not do that,” Cosby informed Dyson, “until you gain clarity.”

Dyson calling Cosby’s message the “blame the poor tour” is anything but confusing. No — Cosby was saying something else: that Dyson is mistelling his own story.

“Sir, I do not have a lack of clarity,” Dyson said. “I have a lack of agreement.”

“Until you gain clarity,” Cosby repeated, “I will not come on your show.”

This was all too much for Dyson, especially Cosby beating up on Katrina victims, co-opting their stories in order to “put his colossal foot on their vulnerable necks. And of all those fellow leaders on that stage in New Orleans, who I knew were disgusted with Cosby’s performance — no one said a damn word to him. That’s nearly as disappointing as Mr. Cosby’s performance itself.”

Why the silence? Because, says Dyson, Cosby’s a powerful guy. You might find the funding for a pet project drying up. Maybe you don’t get on Tavis Smiley’s radio show to promote your book.

Dyson, though, he’s got another book on Cosby coming.

***

The Story That Beth Ferrier Tells

Ferrier, 47, met Bill Cosby in 1984 when she was modeling in New York. They started an affair that lasted about six months. Cosby ended it without explanation. Then he called her one night in Denver, where she lived; they met backstage at a nightclub there, where he was performing. He said, “Here’s your favorite coffee, something I made, to relax you.” She drank it and soon began to feel woozy. Several hours later, she woke up in the backseat of her car, alone. She didn’t know what had happened. Her clothes were a mess, her bra undone. Security guards came and said Cosby told them to get her home. She confronted him at his hotel. “You just had too much to drink,” he told her.

TO GET A HANDLE ON Cosby’s rage, when he spoke in Washington two years ago, and on his subsequent call-out tour, you have to understand the racial torch he’s been holding aloft for some 45 years — and how there’s always been somebody ready to tell him he’s dousing the flame. Cosby created crossover appeal long before Michael Jordan got famous for it, when he hit the New York comedy clubs in the early ’60s with an act that sounds much like the Cosby we all know, albeit younger and peppier, riffing on the stuff of life, like weirdos on the subway, kindergarten, driving in San Francisco.

The problem was, his palatable, life-situation humor didn’t wash once race dynamics, and comics like Dick Gregory and Richard Pryor, got hot. Cosby’s position in 1964 on what his brand of humor could do for race relations never really changed: “A white person listens to my act and he laughs and he thinks, ‘Yeah, that’s the way I see it too.’ Okay. He’s white. I’m Negro. And we both see things the same way. That must mean that we are alike. Right?”

Cosby would be dogged or feted through every career step: He was cast as the first leading black man in a dramatic series, alongside Robert Culp in I Spy, in 1965, even though he’d never acted; it was a little like asking Jackie Robinson to break baseball’s color line without a minor-league stint. Cosby was terrible in front of the cameras at first, stiff and wooden, though he came around: “At 28, Cosby has accomplished in one year what scores of Negro actors and comedians have tried to do all their lives,” Newsweek gushed. “He has completely refurbished the television image of the Negro.” Cosby went on to win three Emmys in the role. In his next TV series, he played Chet Kincaid, a gentle gym teacher who gets caught up in various real-life snafus. But now he was too soft again, with nothing, even the New York Times complained, on “soul culture.”

That’s how it went — Cosby was either a racial leading light or a borderline Uncle Tom. He mined his past to create the Fat Albert cartoon, and even Dyson gives him credit for gracing America’s Saturday-morning boob-tube time with black vernacular and a moral. Yet even the ballyhooed Cosby Show got him into hot water over race in the mid-’80s. Tuning into the Huxtables is such an easy-going, ubiquitous note of rerun culture that it’s easy to forget how groundbreaking the portrayal of a loving, successful black family was, a landmark for blacks and whites alike; it’s also easy to forget how Cosby got hammered for creating a fantasy of urban black America. As for the Huxtables’ unlikely status, Cosby gave reporters an I’m-not-dealing-with-this-anymore statement: “My wife plays a lawyer, and I’m a doctor. For those of you who have a problem with that … that’s your problem.”

When Cliff, Claire and the kids became a number-one show, it was the clearest nose-thumbing he could give two and a half decades’ worth of Bill, you ain’t black enough: Look at this! Success! Everyone relates! The show, and the best-selling books on fatherhood that sprang from Cosby-as-Cliff mania, were the apotheosis. He appeared to be living the simple values of education, of self-reliance, of family. His five kids all had first names beginning with E — for excellence! He’d gotten a doctorate himself, from U Mass. He stayed married to Camille.

How bitterly ironic it had to be, then, that black lower-class culture — especially from his vantage point — seemed to head further south. In the mid-’90s, Cosby paid an unannounced visit to the Richard Allen Homes in North Philly, the project he’d lived in as a kid back in the ’40s; by this point, it was a drug-infested mess. (It’s since been leveled.) In Cosby walked to a central courtyard, alone, revisiting:

“Hey, Dr. Huxtable! Dr. Huxtable is here!” The homeys swamped him. Ain’t that cool, Dr. Huxtable. …

Cosby confronted a guy who looked like a drug addict: What are you doing, this time of day, hanging around? How old are you? Why don’t you have a job?

The guy was 21. He didn’t have any answers. Infuriating, the waste. Cosby himself was utterly self-made. His father was a drunk who abandoned the family for the Navy. Bill himself quit high school for the Navy, came home to Temple, started trying out his native funniness in local clubs, before New York. Was it easy? The screaming matches with his manager after they had taped all six shows Bill would do in a night and gone over every word, to get it right, to make it seem so smooth and simple, as if he just hopped onto the X on Johnny Carson’s stage one day and boom, he was Bill Cosby — it was nothing but a long climb and constant work and fighting for who the hell he was amid all that noise about who he was supposed to be. Now, right here where he grew up, here they were, giving up, gone.

Cosby told the guy at Richard Allen that there was no excuse, that he really had to get it together. So that was the first call-out.

Maybe the gap between how Cosby lived, what he represented, and what he saw of his culture wasn’t bridgeable. As he got older, and lost his only son, Ennis, to a random roadside shooting in L.A. — Ennis, who had overcome dyslexia and had started working with children himself — it only got wider. Now, though, as Cosby tours the country on his call-outs, he’s got Dyson saying that he’s pandering to white America, giving the audience that made him rich exactly what it wants to hear. The noise never ends.

All these deeper hints of Cosby’s personality raise an obvious question. Is the Dr. Huxtable thing — that persona — just an act? Is Cosby a little like the Ronald Reagan that Phil Hartman portrayed on an infamous Saturday Night Live bit, where the president was a doddering, sweet, avuncular fool of a man in public, but behind closed doors barked orders, laid down the law?

No. Writers, producers and directors Cosby has worked with over the years all cite his genius for telling funny stories and his general professionalism. Not tough to work with; intense, sure — “If he’s Dr. Huxtable,” a producer on one of his shows says, “then I’m Mary Poppins” — but certainly not a jerk. And if you go all the way back to the Richard Allen days, you can find a budding Cliff Huxtable. Anita DeBrest, 86 years old, who raised five boys a few doors from Cosby’s home there, remembers him as a child. He would come over and make her laugh, but he seemed manic, like an overactive cat. She thought his fooling around, his earliest comedy, was a way of relieving something “in his heart or on his mind” — later, she heard his parents didn’t get along.

But if comedy was his way of hiding, it was his ride out, too, on a personal level. Cecelia Robinson, a woman he dated back in the early ’60s, while he was a student at Temple, remembers their first date: Bill took her to his house in Germantown, where he’d moved with his mother and brothers; he had the living room decked out like an Italian bistro, with a checked tablecloth, a candle burning in a wine bottle. Bill disappeared upstairs, then reappeared wearing a chef’s toque and an apron, and proceeded to serve Cecelia. … It’s a Cliff and Claire Huxtable bit! They dated for a year, and sometimes, when Bill would pick her up out in Paoli, Cecelia would be upstairs checking herself in the mirror one last time and hear her mother in stitches down there — Bill was a riot. He wanted to be, he told Cecelia, a gym teacher — a gym teacher with five kids. His aunt had some land in Trevose, she would give him a plot, he wanted to give her a friendship ring … Cecelia said no. So Cosby started spending weekends up in New York at comedy clubs, and that was that. Cecelia ended up marrying an eye doctor. Now, after a four-decade break, Bill and Cecelia sometimes have dinner together in Philadelphia, and she passes judgment easily and simply: A decent, sweet, funny guy then. A nice, funny guy now, who, by the way, called 86-year-old Anita DeBrest a couple months ago.

“How you doin’, Mom?” Cosby teased.

“How you doin’, Devil?”

“I’m not a devil anymore.”

One of Anita’s sons — one of the DeBrest boys Bill had been friends with as a kid — had died, and Cosby consoled “Mom” for an hour.

It’s a relief — a relief that the great TV charm of Cosby isn’t somehow an utter ruse. That we weren’t duped, in giving him a pass on a couple things that came up over the years: A woman named Autumn Jackson, claiming to be his daughter, tried to extort $40 million from Cosby in 1997, and he admitted to a “rendezvous” with Jackson’s mother, and payments of more than $100,000 in support over the years. Four years ago, Cosby threw his friend Gladys Rodgers out of his Elkins Park estate after she’d lived there as caretaker for 19 years, because she was practicing witchcraft. Witchcraft?

According to Gladys, it was the Cosbys’ personal “lama” who claimed that Gladys was using blood and sparkle and other stuff to gain control over Bill. Pretty weird. Certainly interesting. But does it matter? Does it have anything to do with the story of … Bill Cosby?

***

The Story That Barbara Bowman Tells

Bowman’s incident with Bill Cosby occurred 20 years ago, when she was an aspiring actress. She told a lawyer. The lawyer laughed at her. She never mentioned it to an authority figure again. Bowman won’t disclose details of what happened before she’s deposed. But when she read about Andrea Constand, she decided that enough was enough — she couldn’t sit in silence any longer. [Bowman later gave an extended interview that was published in the November 2006 issue of Philadelphia.]

BUT, OF COURSE, personality can be superficial, itself an act. Personality is, when you’re as charming and funny as Bill Cosby, useful.

Back in Greenwood, Mississippi, on that Monday in late April, Bill Cosby works very hard into the evening, and uses every ounce of the “Bill Cosby” we love. During the second call-out, where half a dozen local folks tell stories of coming back from the excesses of drugs, sex, and violence, Quiana Head, a lovely 27-year-old hairdresser and youth director for a Christian organization, begins by saying she had a daughter when she was 14, that she’s “now 27 years young and did everything under the sun.”

“What was under the sun?” Cosby wonders in mock innocence.

“Everything,” Quiana admits. “I was madly in love with a married man.”

“Look out!”

“ … 11 years older than me … ”

“WHOOOO … ”

“I spent three days in Clayton County Jail.”

“With him?” Cosby deadpans.

The crowd is roaring.

Then Quiana tells her story, but she isn’t doing it to Cosby’s satisfaction, because, as she tells it, she was a mess, and then she found Jesus. A simple segue. Cosby has to join her, center stage.

“When you found out you were pregnant, how far ahead could you see?” he wants to know. “At 13, what were you ready for?”

“Nothin’.”

“At 13, do you have a job?”

“No.”

“This is a wonderful message that I want to go out to parents who are afraid to talk to their daughters. … But you’re skipping over the good parts. I want you to talk about how frightened your little behind was.” Cosby won’t let her off the hook. No, there’s more to the story, having a baby at 14, and finally Quiana tells the audience:

“I didn’t become this little promiscuous kid just because I woke one day and became that. … I was sexually molested as a little girl for years.”

“Now you’re telling it!”

“I was a very angry kid. My mom was raising five children, working at a catfish farm.”

“No, we didn’t hear about all this.”

Oh, he is working so hard here, getting to the fundamental thing, the real thing, which is that Quiana did this herself. Got well herself. It was within her. And she goes on to say that her life was such a mess that — and Cosby knows there is another hurdle coming — she was suicidal, and cried herself to sleep with a loaded .25 on the bed next to her.

The hurdle isn’t suicide, but Jesus. So now Cosby must massage the meaning of Jesus coming into her life — not for her, but for the greater audience:

“Whatever Jesus was doing,” he says, “Jesus is in you. So as you were crying, something washed, and you looked at everything you were and had been, had been, because that night, it was over, Sis. It was over. You were ready to commit suicide. … The selfishness of yourself, to take your life, leave [your daughter] with your mother, and you cried, and it washed all of the foolishness out of you.”

In other words, she did it. “And then,” Cosby allows, but it is clear this isn’t his driving idea, “the Jesus in you grew.”

Quiana sits down.

It is a beautiful, and dangerous, moment. Cosby pushed her, which was important. Then he told Quiana the meaning of her story. He did not try to take away her idea that Jesus was a big help, though he made it clear: If you’re going to go to Him, you’re not off the hook. And, of course, she’s just the proxy for his message to the crowd, and the public-radio audience in Mississippi listening in, and anybody who will watch the documentary being filmed here and now. Bill Cosby wants the world to know: Personal responsibility is the name of the game.

Which could be the rallying cry of the 13 women, witnesses in Andrea Constand’s civil suit against Cosby, now standing up and telling their stories too, after years of silence. Tamara Green, the California attorney who explained hers on TV, said, “This is about dominance and submission. … These are helpless women that he’s been doing this to.” Women who were afraid to tell their stories. Women who, to Bill Cosby, have no stories at all; he said he didn’t even recognize the name Tamara Green. But now, they’re going deep into their own pasts. They’re no longer skipping over the good parts, because one woman came forward with a story that sounds similar to their own.

Meanwhile, Bill Cosby pushes on, with the will and defiance to ignore what amounts to the minutiae of a personal issue, a legal matter, when you consider what these women are saying against all he has accomplished, all that he is still trying to do, that he must do. When you consider it against being … Bill Cosby. That will and defiance, and the certainty that he’s got to spread his word, will keep echoing around arenas and halls and civic centers all over America. Which is beautiful. What a grand attempt!

Late April in the Delta, close to the end of his final rallying speech, Cosby asks for everyone with a family member who’s been shot to stand up. A few do.

“They have no business having guns! … When are we going to talk to our children? People have guns, and no practice range, so they hit children. …

“Christians, you need to revisit salvation, and what Christ really is, in terms of you. Because Christ is in you. And if Christ is in you, then stop this madness.

“I don’t think God intended you to sit on your behind.”

It is a long, long stretch Bill Cosby is making from stand-up comedy, working, deep into his seventh decade, to hang on to, and shape, his own story. Maybe, in the attempt, he will save himself.

Originally published in the June 2006 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

RELATED: “Cosby Threw Me on the Bed” (November 2006)