If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Philly Moments That Made Us Proud in 2025

2025 was a year when kids became heroes, sports took the spotlight, and our sandwich finally got its due.

7 Reviews That Defined Philly Dining in 2025

Spread at Little Water and Amá’s wood-fired octopus / Photography by Gab Bonghi (originally published in “Little Water: A Poetic Exploration of Land, Water, and Comfort Food)” and Bre Furlong (originally published in “This New Philly Restaurant Is Raising the Bar for Mexican Food“)

2025 was Philly’s year.

In terms of dining, anyway. In professional kitchens and dining rooms, at barstools and banquettes, 2025 was the year that Philly came to play. And even if, in our hearts, we will always be the underdogs — even if (and I hope this remains true) we will never, ever care what the rest of the world thinks of us — Philadelphia’s chefs and restaurateurs and everyone who fills the seats every night knows that this moment? It’s special.

So how lucky am I that I got to spend my year eating my way through what will likely be some of the most remarkable seasons in Philly dining history? It was a year that began with cheesesteaks, had cheesesteaks in the middle, and kinda ended with cheesesteaks, too. It had everything in it that comprises the complete Philadelphia food pyramid: Pizza, genius, comfort, tacos, pasta, hot dogs, sushi, fish caramel, and Wawa. And my reviews covered everything from heavy metal corndogs and Georgian khachapuri to brilliant tasting menus, killer cocktails, and a Wes Anderson version of a French grocery on East Passyunk.

It was a really good year for eating, is what I’m saying. And looking back on it now, I think there were a few distinct moments that really explain what it was like to dine out in Philly in 2025. And it all began with …

An Octopus in Ambler

Carnitas de pato and ravioles de aguacate con cangrejo from La Baja / Photography by Breanne Furlong (originally published in “La Baja Is Chef Dionicio Jiménez’s Best Cooking Yet“)

“On a freezing night in Ambler, deep in the post-holiday slump, I slide alone into a two-top table at Dionicio Jiménez’s new restaurant to eat roasted baby beets sprinkled with pistachios in a homemade crema called jocoque — brought to Mexico by Lebanese people fleeing the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century — and a chile relleno stuffed with scallops and chorizo under a blanket of melted queso asadero and swimming in a pool of Thai green curry. On the wall above me, there’s a sculpture that I love. It’s big, garish, weird — an elephant head with blue butterfly wings and an octopus body, arms writhing against the whitewashed brick in the main dining room.”

That’s how my year started — alone in the suburbs eating a remarkable dinner under the gaze of the alebrije that watches over Dionicio Jiménez’s dining room at La Baja. We may have lost Jiménez’s beloved Cantina La Martina this year, but I spent most of 2025 telling anyone who would listen that La Baja — with its chimeric menu of duck bao and corn ribs and ramen dust — is actually the restaurant that we should really be paying attention to when it comes to what’s coming next, both from Dionicio and the food world as a whole.

Fire and Metal

A seafood tower at Jaffa and a mapo chili dog and the Gintonic at Doom / Photographs by Ed Newton (originally published in “The Jaffa Paradox: A Buzzy, Bright Space That Feels Surprisingly Hollow“) and Courtney Apple (originally published in “Doom: Where Metal Meets Corn Dogs and Cosmic Brownies)“

Jaffa, March 2025 and Doom, April 2025

“There is a part of me that always believed I would find myself alone at a metal bar drinking gin at the end of the world. There is, maybe, a part of all of us that believed that. Some piece of our collective consciousness, steeped in the opening montages of a hundred different post-apocalyptic films, that knew this moment was coming and was just waiting for it to arrive.

What’s surprising, though, is that the hot dogs are so good.”

These two reviews — of Michael Solomonov’s Jaffa in Kensington and Justin Holden’s Doom on 7th Street in Callowhill — ran in back-to-back issues, and they were both, in their way, about size. Physical, emotional, psychological — they were about the kind of real estate that a bar or a restaurant can take up in your head before you even walk through the door. The Jaffa review was about an oyster house, but it was also a meditation on expectation and disappointment. On the dissonance of competing visions. Doom was mostly about hot dogs, cosmic brownies, D&D, and where we want to be when it feels like the world is coming apart around us. Separately, they are just reviews of two very different restaurants. But looked at together, they say something about Philly’s growing pains and how to stay true to yourself and the things you love in the face of success.

A Fish in the Clouds

Spread at Little Water (clockwise from left): Halibut; raw bay scallops; hash browns with crab and uni; peekytoe crab salad. / Photography by Gab Bonghi (originally published in Little Water: A Poetic Exploration of Land, Water, and Comfort Food)

A piece of halibut, some potatoes, a couple clams, and a lifetime of practice: That’s all it took to assemble the plate that stands as the single most memorable dish I had in 2025.

“There is nothing in the world more comforting to me than fish and potatoes. In my worst moments, that is what I’ve craved. In my best, that’s how I’ve wanted to celebrate. A simple piece of fish, a little starch, warm and filling. It says sunlight and the sound of water to me. It speaks of a friend’s bar in the mountains where my comfort order was a piece of sole, a white wine beurre blanc, and mashed potatoes. And I suspect it says something similar to the Ruckers. That somewhere, they’ve felt that same comfort, and here, on this single plate, have chosen to glorify it with a simple fish and gorgeous technique. That, at its heart, is what all of Little Water is about.”

At Little Water, Randy and Amanda Rucker served me what was probably one of the two most moving plates I had all year. They also served me one of the most beautiful. And what’s amazing is that they weren’t the same plate, but they arrived during the same dinner — just one random evening in Rittenhouse, in the spring of this notable year.

Green Is the New Black

The dining room at Emmett / Photograph by Ed Newton (originally published in “Inside Philly’s Most Inventive New Restaurant“)

“I know this place. I’ve been here before. The longer I spend eating my way through this city — the longer anyone does — the more things repeat. The more I end up sitting in dining rooms, sharing space with the ghosts of meals gone by.”

I ate here once without really thinking about it. Then I came back because I couldn’t stop. There’s something about the way chef Evan Snyder’s Emmett is, in its own, quiet way, defining an entire sector of Philadelphia’s dining scene right now: a kind of soft, easy, customer-focused (rather than ego-driven) experience that stands just outside the bright spotlight of glossy acclaim (though that may change now that tastemakers outside of Philly are starting to notice the place). I’d get there soon. And don’t sleep on the prix fixe.

Changing the Game

Amá’s wood-fired octopus / Photography by Bre Furlong (originally published in “This New Philly Restaurant Is Raising the Bar for Mexican Food“)

“There’s no time to eat everything I want to eat, no space here to tell you about the custom roasting and smoking grill Ramirez had installed in the kitchen, or the charmingly awkward first date at the table in front of ours, or how Ramirez brought his mom in from Mexico just before opening to teach him how to nixtamalize corn, or even about the brilliant tequila- and mezcal-heavy cocktails with their tomato shrubs and chapulin garnishes. But I tell myself that next time I come here, I will get an Uber so that I can drink my way down the list without having to worry about finding my car. I tell myself that next time, I will come late when the lights are low, close the place, and walk out into a city and a neighborhood that will be defined by food exactly like this in the future, that will remember Amá maybe not as the start of something, but absolutely as a continuation of an edible conversation Philadelphia has been having with itself for the past 20 years.”

If you want to understand anything about where Philly’s food scene is headed in the future, Amá is where you should start.

The Stories We Tell

Cybille St. Aude-Tate and Omar Tate at Honeysuckle / Photograph by Gab Bonghi (originally published in “Why Honeysuckle Is the Most Important Restaurant in Philly Right Now“)

At Honeysuckle, Omar Tate and Cybille St. Aude-Tate are using their space to tell a multi-layered (and multi-media, and multi-generational) story of Black foodways that speaks very loudly to this particular moment in Philly. All its recognition aside, Honeysuckle is a beautiful example of how dedicated artists can use every piece of their restaurant and every part of themselves to tell the story they want to tell — from jumped-up Big Macs that tell about burning money you don’t have, to vegetable boards that serve as lessons in geography, history, horticulture, and cuisine all at the same time.

Mostly, though, the place is just good.

“Not every dish is a manifesto. Not every dish needs to be. The hush puppies? They’re merely delicious: golden brown, set in thick dots of Cajun holy trinity relish (onion, bell pepper, and celery, which reappear as a digestif soda at the end of the meal), wearing marbled pink hats of country ham. And the seafood Alfredo is pure ego from the kitchen in the best possible way — edible proof that in this town where Alfredo is the mother of a thousand menus, their version (smooth as easy listening, rich as a crooked minister, made with crème fraîche, local shellfish, hand-cut tagliatelle, and a custom Bay spice blend they call New Bay Spice) can compete.”

I called Honeysuckle the most important restaurant in Philadelphia right now. And that may be true, but it has a lot of competition.

Philly is about the big and the small, the fancy and the plain. It is equal parts tasting menu and Sunday gravy, cheesesteaks, and caviar. And I wouldn’t want to live (or write) in a place that was any other way. This year gone by might stand as one of the most important, most formative, most definitional in the history of Philly’s modern restaurant industry, but 2026 is already peeking ’round the corner. And speaking as one of those guys who tracks chefs and restaurants and the energy of this industry, like that one weird friend you got who just can’t stop talking about crypto, I can confidently say that next year is already shaping up to be a banger, too. Maybe we get even bigger. Maybe it all falls apart. Maybe we never see another year like this one ever again.

2026 is where we’re all going to find out.

See y’all there.

Love & Honey Reveals Plans to Open Six New Locations

Photograph courtesy of Love & Honey

Howdy, buckaroos! And welcome back to the weekly Foobooz food news round-up. With Christmas nearly upon us, things are pretty quiet in restaurant world this week. So how about we just get through a few quick things, including (but not limited to) Greg Vernick’s new restaurant, fried chicken in Bryn Mawr, the end of the line for Blackfish, and a couple suggestions for your New Year’s revels. After that, we can all get back to our last-minute holiday shopping and watching Christmas specials on the couch. So let’s start this final round-up of the year with …

Love & Honey on the Main Line

No one really thinks of Bryn Mawr when it comes to scoring good fried chicken, but that should change with the opening of the newest location from NoLibs-based Love & Honey.

I first reviewed the place way back in 2017 and fell in love with the long-brined, crisp-skinned chicken that chef Todd Lyons spent years working on before he and his wife, Laura, first went looking for a space. Now, it is eight years later. Questlove and Kylie Kelce are both big fans. Love & Honey has a location in Newtown. And the newest spot, at 1111 Lancaster Avenue in Bryn Mawr, just opened.

It’s a small space with a short counter and a handful of tables in a former car dealership, redeveloped for retail and upstairs apartments. The menu is exactly what you’d expect — chicken sandwiches, wings and tenders, legs and thighs, with sides of tater tots, potato salad, pimento cheese dip, and banana pudding for dessert.

The new Bryn Mawr spot is a franchise, and it’s not the only one on the books. Word is, there’ll be at least three Main Line locations, plus new shops coming to East Passyunk, King of Prussia, Cherry Hill, and University City. There are also expansions planned for other states, but those matter less to me. No reason to drive all the way to Washington D.C. when I’ll soon be able to get my fried chicken fix in South Philly.

So anyway, 2026 is looking to be a big year for Love & Honey. And it’s about time I got back to check the place out again.

In the meantime, what else is happening this week?

Some Bad News for the End of the Year

Blackfish BYOB’s seasonal menu / Photograph courtesy of Blackfish BYOB

I don’t mean to bring anybody down here as 2025 winds to a close, but we’ve got a couple closures that are worth talking about before we wrap thing up for the year.

First, in Conshohocken, it looks like Chip Roman’s Blackfish — the BYO he opened way back in 2006 after time spent working for some of the city’s heavyweights (Georges Perrier, Marc Vetri, etc.) — is going to be shutting down on New Year’s Eve after nearly 20 years of service.

Blackfish has been a part of Philly’s restaurant scene for as long as I can remember. It made it to the top of our 50 Best Restaurants list in 2011 — in the days before most of the chefs working in the city’s best restaurants now had even opened their first restaurants — and I wrote about it five years after that, checking in to see how the place was holding up just as the scene was beginning to boom with places like Double Knot, Laurel, Fork, Vedge, and Greg Vernick’s first spot. It is one of those places that has encompassed the whole history of Philly’s second restaurant renaissance; that’s been there through all the ups and downs. And now Roman has decided that it’s time to turn out the lights.

“After nearly 20 years, I’ve made the heartfelt decision to close Blackfish BYOB and begin the next chapter of my life,” he wrote on Instagram. “This is not a decision I made lightly — this restaurant has been a defining part of my story, my work, and my heart.”

New Year’s Eve will be the final night of service at Blackfish.

On the same day, we’ll also be losing the Fishtown location of Goldie at 1601 North Front Street. CookNSolo announced (also on Instagram) that their falafel-and-milkshake spot would be ending its run after three-ish years and that the space will be becoming a part of their event venue, Lilah.

The other four Goldies? Looks like they’re all good for now.

Greg Vernick’s New Spot

Chefs Meri Medoway and Greg Vernick making pasta. / Photograph by Liz Barclay

In case you missed it last week, we had all the details on the new restaurant coming from Greg Vernick and long-time chef de cuisine Meri Medoway.

The new spot will be called Emilia, and they’re hoping to have it open early next year at 2406 Frankford Avenue in Kensington. It’ll be a mid-sized spot (80 seats, give or take), with bar and lounge seating held for walk-ins. The menu will be Italian, pasta-focused, and feature plates coming off a wood-fired grill because that’s become something of a defining flavor for Vernick’s restaurants. There’ll be six pastas, a mix of small and large plates, tortellini in brodo, rabbit cacciatore and a chicken ragú bianco. Medoway will be in charge of things on the line, and the menu is a collaboration between her and Vernick, focusing on dishes that they’ve loved, things they’ve eaten during research trips to Italy, and plates that have meant something to them across the years that Medoway has spent working in Vernick’s kitchens (she started at the O.G. Vernick as an intern back in the day).

Best guess for an opening night is early 2026, but I hear that the team is pushing hard for something in late January. So there’s something to plan for in the new year, right? Having something to look forward to is always nice.

Speaking of the New Year …

There’s two pretty awesome parties you should know about: One on New Year’s Eve, the other on New Year’s Day.

First, on NYE, Southgate is doing a late-night, all-you-can-eat spread with an open bar from 10 p.m. ’til just after midnight. There’ll be mountains of Korean fried chicken, bao buns and fries, plus an open bar pouring bubbly wine and cocktails. I like this one because Southgate is one of those places that we just don’t get the chance to talk about enough — a solid, dependable neighborhood spot that has served me well on countless occasions. These days I don’t get there nearly as much as I used to, but one of my resolutions for the new year is to remedy that.

Tickets for the New Year’s Eve party are $100 and you can get yours by emailing the restaurant here.

Then, on New Year’s Day, there’s Harper’s Garden. They’re offering space for four to six people in their newly re-done Garden Cabins if you’re looking for a spot to gather for brunch. So if you’re looking for beignets, avocado toast, pancakes, breakfast tacos and strawberry shortcake zeppoles with a few close friends to kick off 2026, this is your spot.

Reservations are available for the New Year’s Day brunch in the cabins (or in the restaurant, for larger parties) from 10 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. You can get yours right here.

Looking for more? Check out Philly Mag’s guide to New Year’s Eve celebrations around town.

Now who has room for some leftovers?

The Leftovers

If you’re looking for something else to do on New Year’s Eve, the crew at Andra Hem (whom we talked up in our recent cocktail package) is partnering with Party Girl Bake Club for a one-night-only shot of sweetness to ring in the new year. Andra Hem will be serving Princess Cakes, courtesy of PGBC — classic Swedish desserts made of vanilla custard and raspberry jam squished between two layers of angel food cake. Reservations are still available if you’re looking for a place to hang out, drink, and eat cake.

Speaking of Andra Hem, after New Year’s, they’re rolling out three new mocktails for Dry January, including the Squirt Gun (which is a shot of espresso and bitter soda), and The Linc with cucumber water, dill and lime (because they’re all green, get it?). And over at Wilder, they’re running with a whole menu of N/A cocktails for January, including a vanilla and lime sarsaparilla, Top Shelf Bubbles with orange, lime and non-alcoholic sparkling wine, and a rum, coffee and condensed milk cocktail made with Philter’s N/A rum.

Finally this week, The Buttery in Malvern is working to keep everyone warm this January with a month-long Bread & Soup Club.

Every Thursday, they’ll be doing a new soup, paired with their house-made sourdough, for pickup only. Basically, they’re doing weekly hot soup and fresh bread dinners for you to take home with you, with options for two or four people, plus a variety of add-ons. It’s a subscription service, so you’re buying in for all four weeks. Pickup is at the Malvern location at 233 East King Street.

But hey, if you’re looking for some easy dinner solutions in January — or a last-minute gift idea for someone who could use some warm soup — this is perfect. Sign-ups will be available through January 3rd. Soup for two for all four weeks will run you $100. And you can sign up for The Buttery’s Bread & Soup Club right here.

This W Philadelphia Proposal Was a Family Affair

David Young proposed to Olivia Jo Wilson at the W Philadelphia. / Photography by Angela Gaspar Photography

What’s more romantic than a view of the Philly skyline? How about a proposal overlooking the city? That’s why the W Philadelphia’s terrace remains a popular spot for popping the question, with everyone from Eagles wide receiver DeVonta Smith to pro golfer Matthew Wolff getting down on one knee there. Here, you’ll read about another big moment, staged shortly before the holidays and captured by Angela Gaspar Photography. Need even more proposal inspo? Click here.

The couple: Olivia Jo Wilson, 24, and David Young, 24, both of Elkton, Maryland

How they met: David and Olivia have known each other most of their lives. They attended elementary school, middle school, and high school together; but didn’t start dating until December 2019, when they took a trip to New York City.

The proposal: David and Olivia both love Christmas — so what better way to kick off the holiday season than with a November proposal? The engagement, which took place at the W Philadelphia, was a family affair. David’s mother decorated the terrace — which boasts stunning views of the city skyline — with candles, lanterns, rose petals, and four white rose, hydrangea, and lily floral arrangements, which she made herself. Olivia’s mother and Olivia’s best friend also helped out. And they all made sure David and Olivia’s one-year-old son was there for the big moment. After the “yes”? Champagne was popped, and the couple’s family and friends joined them on the terrace to celebrate.

Her reaction: Olivia says she was in utter shock. “I just felt so much love in the moment,” she says. “It was beautiful in every way, and it was so special.”

His reaction: Dave simply wanted everything to go off without a hitch. “I wanted to make it special for her because she is so special to me,” he says.

The post-proposal moments: The couple later enjoyed dinner at Butcher and Singer, where Dave revealed he had one more surprise: He’d invited their friends to celebrate their engagement with a night out in the city. “We walked all around town and enjoyed the night life,” Olivia says of the after-dinner festivities.

The wedding plans: Dave and Olivia are soaking up that soon-to-be-wed feeling right now — and since they both love Christmas, they’re eyeing a December 2027 wedding.

Get more great content from Philadelphia Wedding:

FACEBOOK | INSTAGRAM | NEWSLETTER

Philly Mag’s Favorite Long Reads of 2025

Settle in with some great Philadelphia magazine long reads from 2025.

It can be hard sometimes, in the daily throes of magazine creation, to take a step back. There are deadlines, busted deadlines, production snags, and photography snafus, and then it’s Tuesday and you start all over again.

So at the end of every year, it’s good to stop for a minute and reflect on the good work you’ve done. In that spirit, here are some of our favorite long reads from 2025, which, looking back, featured a surprising number of stories that take place on or around highways? (See, it’s good to reflect!)

Here are our favorites for 2025 — and check out our full archive here.

“I Hope Your Team Sucks and Loses”: Inside the Head of John Kruk

John Kruk / Illustration by Britt Spencer

If you’ve ever tuned in to a Phillies game on NBC Sports Philadelphia, you know that John Kruk isn’t your typical broadcaster. He’s unfiltered, hilarious, and refreshingly honest — sometimes to the point where you wonder if the producers are sweating behind the scenes. But that’s exactly why fans love him.

In our March issue, Jake Kring-Schreifels dove into what makes Kruk such a unique voice in the Phillies booth. From his no-nonsense takes on the team’s performance to his self-deprecating humor and random asides on everything from Dance Moms to giraffe encounters, Kruk brings an authenticity that’s rare in today’s polished sports media landscape. Keep reading here.

Steven Singer Loves the Haters

Steven Singer sporting the diamond ring he offered Travis Kelce for free to give to Taylor Swift / Photography by Jonathan Pushnik

You know the name. You’ve seen the billboards. Maybe you’ve even wondered who exactly it is who hates Steven Singer, and why? But how much do you really know about the man behind one of Philly’s most recognizable brands?

Emily Goulet took readers inside the wild world of Steven Singer — the jeweler-turned-marketing-mastermind who built an empire on audacity, innovation, and just a little controversy. From his ubiquitous “I hate Steven Singer” ads to his partnership with Howard Stern to viral marketing stunts, he’s become a Philadelphia institution.

But this isn’t just a business story — it’s personal. Singer has battled health scares and navigated the changing retail landscape, and now he faces the biggest challenge of all: ensuring that his brand thrives without him. Keep reading here.

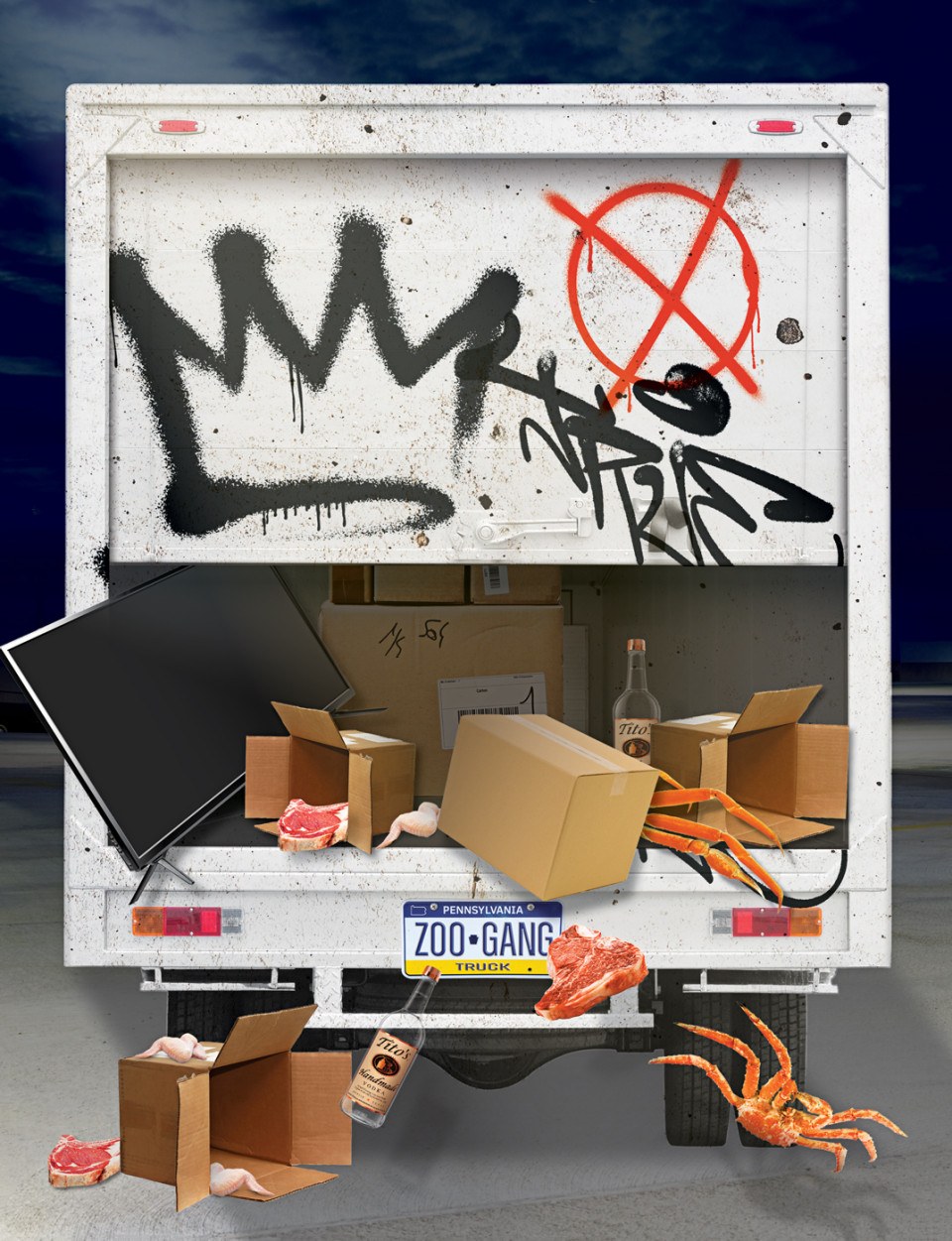

The Beef Bandits of Nicetown: Inside the Biggest Cargo Theft Ring in Modern Philadelphia History

Snow crab legs. Chicken wings. Thousands of pounds of beef. Inside Philly’s biggest cargo theft ring in modern history. / Photo-illustration by Leticia R. Albano; images via Getty Images

Snow crab legs. Chicken wings. Thousands of pounds of beef. That’s just part of what one North Philly crew managed to jack in a cargo theft operation so big the feds had to step in. Since 2022, freight had been quietly vanishing from delivery trucks before ever reaching restaurants and stores. At first, police were left scratching their heads. How were entire trailers of meat disappearing in broad daylight without a trace? But what looked like a few scattered heists soon revealed a pattern — and a level of coordination that pointed to something much bigger than a couple of neighborhood guys with bolt cutters.

Matthew Korfhage followed how a web of North Philly crews evolved from street-level operations into something that resembled a full-blown criminal enterprise — one that stole everything from 10,000 pounds of dimes to 10,000 pounds of turkey wings.

What makes this story so compelling isn’t just the scale of the heists — it’s what they reveal about the evolution of street crime in Philly. Keep reading here.

How One Store Became Ground Zero for West Philly’s Gentrification War

Baltimore Avenue / Photograph by Nazir Wayman

Baltimore Avenue has long been one of West Philly’s most iconic streets, a place where coffee shops, salons, art spaces, and dive bars lived side by side. But lately, the corridor has felt … off. Storefronts sit vacant for months. Beloved local businesses close. In their place, soulless vape shops pop up, sparking confusion and frustration. Is the avenue gentrifying? Declining? Stuck?

A discount “bin” shop of castoffs and returns from places like Amazon and Costco was the final straw for Jen Kinney, who, for our October issue, explored the tension at the heart of West Philly right now: a neighborhood that fiercely protects its identity and values local ownership, but is also craving new life, new hangouts, and yes, even a decent cocktail bar. Residents want businesses that are affordable but not “cheap,” modern but not corporate. It’s far more complicated than a simple boom-or-bust narrative.

Beyond the anecdotes — the bar destroyed by a fire, the ice cream shop that never came back — Kinney zooms out to expose the structural forces shaping Baltimore Ave: rising rents, online shopping, pandemic aftershocks, zoning roadblocks, and the financial squeeze on small businesses. It’s a window into the future of every city corridor fighting to save — and stay — itself. Keep reading here.

Highway to Hell: Inside PennDOT’s Plan to Widen I-95 Through South Philly

The I-95 expansion will change the landscape of Philadelphia neighborhoods. / Photography by Kyle Kielinski

In South Philly, PennDOT’s proposal to expand I-95 has stirred fierce pushback from residents who say those plans could swallow up community sports fields and repeat the mistakes of the past. Decades ago, the original highway carved through neighborhoods, displacing families and fracturing communities. This time around, as David Murrell reported in March, locals are organizing to make sure their voices can’t be sidelined again. Their fight is about more than just a highway — it’s about what our city prioritizes, and who gets a say in its future. Keep reading here.

Can Mussels Save Philadelphia’s Waterways?

The Philadelphia Water Department’s Lance Butler and William Whalon in the Manayunk Canal / Photography by Gene Smirnov

What if the key to cleaning up Philly’s rivers isn’t some futuristic gadget or expensive new plant, but … mussels? Yes, the same humble shellfish you might order with frites could be the city’s secret weapon in the fight for cleaner water. In our September issue, Cari Shane took us inside a first-of-its-kind Philadelphia Water Department project that could transform our waterways forever.

Mussels are nature’s filtration systems, and reintroducing them into local rivers and streams could yield monumental results. Each adult mussel can clean six to 10 gallons of water per day. Now multiply that by the millions of mussels PWD hopes to put into our watershed.

Biological wonders aside, this story has a bit of hopeful magic to it. It’s about looking at an old problem with fresh eyes, and finding an unexpectedly simple, elegant solution. Instead of a massive high-tech intervention, the city is betting on something small, natural, and kind of beautiful. It’s the sort of idea that makes you stop and think about how interconnected everything is, and how sometimes the best fixes are already part of the world around us. Keep reading here.

Billboard Wars: How Personal Injury Lawyers Took Over Philly

Personal injury lawyer billboards all over Philly / Photography by Jeff Fusco

If you’ve driven down I-95 or scrolled through social media, you’ve seen them: bold personal injury ads promising big payouts for your misfortune. “Jawn” Morgan, TopDog … they’re unavoidable. But beyond the catchy slogans and smiling lawyers, these ads are shaping more than just the legal industry.

In our February issue, Tom McGrath explored how the explosion of legal advertising has fueled a rise in lawsuits, record-breaking jury verdicts, and even higher insurance costs. Some firms now operate more like marketing machines than like traditional practices, spending millions on advertising to bring in a steady stream of cases — and, ultimately, big-dollar verdicts.

The success of this model is driving a transformation in the legal industry, with large firms dominating and smaller ones struggling to compete. “Perhaps such an evolution was inevitable,” McGrath writes. “If, 120 years ago, America’s energy was being put into high-minded civic reform, today it flows mostly into creating ever more robust bottom lines.” Keep reading here.

Phila and Rachel Lorn’s Trick to Success? Desperation

Rachel and Phila Lorn / Photography by Stevie Chris

Change is hard, especially for those of us blessed with stubbornness. For Phila and Rachel Lorn, the owners of Mawn, change has come in waves this year: Phila’s James Beard Award for Emerging Chef and Best New Chef honor from Food & Wine, a spot on the New York Times Best Restaurants in America list, a new oyster bar concept down on Passyunk — and the dozens-deep lines that come with all of that.

Jason Sheehan spent time with the couple as they navigated this new reality, one where in just three years they’ve gone from opening their first restaurant to the top of the food world. Sometimes, the best Philly restaurant stories aren’t just about food — they’re about fight. Phila’s journey — from growing up in a Cambodian refugee household to navigating years in the city’s restaurant scene — is a story about hunger in every sense of the word.

Phila and Rachel Lorn’s path to acclaim wasn’t glamorous: There were near-deals gone wrong, pandemic setbacks, and nights wondering if the dream would ever happen. But when they finally opened Mawn on 9th Street, it was proof that they could make something real simply by believing in it. In a city that celebrates grit, Mawn feels like the ultimate Philly story — equal parts love, risk, and rebirth. Keep reading here.

50 Years of Fresh Air: An Oral History

Fresh Air’s Terry Gross in the early ’90s / Photograph courtesy of WHYY

Fifty years ago this past September, Terry Gross, just 24, sat down in the host chair and turned Fresh Air into a genre-defining radio show. It’s been a soundtrack of American culture — and at its center are Gross’s warm, incisive interviews that have become the gold standard in radio. Gross has talked with more than 13,000 guests, shaping their stories into conversations that feel both intimate and revealing. Her preparation is meticulous, but her curiosity is the key. “I’ve always thought of myself as a big ear when I’m doing an interview,” she tells Pete Croatto in his oral history of the show.

But, as Croatto reveals, Gross’s path to broadcasting was anything but straightforward. It wasn’t until she stumbled into college radio that she found the medium that would define her career. What followed was decades of persistence, creativity, and collaboration that transformed a scrappy Philly show into one of NPR’s most beloved national programs, now heard by millions every week. Now 74, Gross has cut back her hours but has no plans to retire. Fresh Air remains a touchstone — a daily reminder of the power of listening, shaped by the dedication and artistry of its longtime host.

Croatto’s oral history takes us from the leaky WHYY offices where Gross once worked alone to the present day, as she adapts to a changing media landscape. Along the way, meet the people behind the scenes — from early allies to famous guests — who helped the show become the cultural force it is today. Keep reading here.

Inside Pennsbury High’s Legendary Prom: The Most Epic School Dance in America

Pennsbury High School Prom / Photography by Dina Litovsky

Every spring, Pennsbury High School pulls off something few communities can even dream of: a prom so massive, it takes a six-figure budget and an army of volunteers to make it happen. We’re not talking some glitter and streamers in a gym — this is a full-scale production with giant art installations, elaborate themed sets, special effects, celebrity performances, and a pre-prom parade.

As Emily Goulet revealed in her epic behind-the-scenes story, what makes this prom remarkable isn’t just the spectacle, but the way the entire community rallies to create it. Parents, alumni, and neighbors spend months painting, building, and fund-raising, transforming the school into a magical place for one incredible night. It’s as much a community tradition as it is a student dance. Keep reading here.

Josh Shapiro’s Next Big Step

Josh Shapiro / Photograph by Colin Lenton

Josh Shapiro has been a fixture in Pennsylvania politics for two decades, but his profile has never been higher. For our July cover story, Tom McGrath took readers inside the political calculus and personal ambition of a guy who’s never lost a race, has a knack for showing up at just the right moment, and might just have his sights set on the presidency.

McGrath followed Shapiro from a high-powered DNC dinner in Philly to a timber mill in deep-red Mifflin County, and into the thick of a vice presidential vetting process that nearly landed him on the 2024 ticket. It’s a rare unguarded look at a politician whose steady rise has been anything but accidental. “To his supporters,” writes McGrath, “Shapiro’s unbroken climb is evidence of his rare political talents. To his critics — and there are plenty, including some Democrats — his steady ascension reflects something else: cold ambition. There’s nothing that says both can’t be right.”

As 2028 looms and national attention turns our way, McGrath offered a personal, layered portrait of the governor. Keep reading here.

How Surfside Took Over the Cocktail World

Riding the undeniable wave of Surfside / Photo-illustration by Andre Rucker

You’ve seen the sunny, striped cans. You’ve probably had one at a tailgate, on the beach, or at a backyard barbecue. From its humble Philly beginnings, Surfside is now a national brand that’s exploded into one of the fastest-growing drinks in the country. The proof is in the crushed cans: “They don’t teach you this in business school, but if you really want to know what the people of your town or city are drinking, all you have to do is look at the ground,” says Surfside co-founder Bryan Quigley.

Emily Goulet traced the story behind Surfside — from the early days of distilling vodka with a makeshift, “legally dubious” still in a basement to becoming a beverage company that’s now moving millions of cases annually. What sets this story apart isn’t just the product’s rise, it’s how it happened. The team behind Surfside relied on gut instinct, word of mouth, and a relentlessly hands-on approach. They made something no one else was making, and watched demand explode. “No one in Big Beverage realized what this little distillery in Philly was doing until it was impossible to ignore,” writes Goulet.

Surfside’s success story is a wild, Philly-born ride that’s still unfolding. Keep reading here.

Mark Your Calendar: We’re Hosting Pilates Classes in January

Our Pilates series with Coach Zha (pictured) will take place on Janaury 4th, 11th, and 25th. / Photograph by Linette Messina

Hey, Be Well Philly fam!

To move together in the new year — and to celebrate our latest print issue — we are hosting Pilates classes this January. (Woohoo!)

Join us on January 4th, 11th, and 25th for mat and reformer sessions led by Zha Dadson, a.k.a. “Coach Zha,” who is featured on our most recent cover, earned the title of Philadelphia magazine’s 2025 Fitness Influencer of the Year, and is a Best of Philly winner.

Each Pilates class will be held at Lumos Yoga & Barre’s Spring Garden Street studio (1822 Spring Garden Street) and will begin promptly at 1 p.m. You can arrive as early as 12:30 p.m. to check in, stretch, and get situated. Mats and props will be provided.

The classes on January 4th and 25th will be mat-based, while the workout on the 11th will take place on the reformer. Each session will be accessible to all fitness levels — no experience needed!

Even better: There’ll be treats from Brewerytown-based juice and smoothie bar Blkberry for you to enjoy post-sweat sesh. Attendees of the first week’s class will also receive complimentary Philly-themed grip socks from Socks & the City.

Tickets are on sale now! Spots are limited, so snag yours ASAP.

We can’t wait to start 2026 off strong — together!

4 Philly Stretch Centers to Help You Loosen Up

Stretching out at Lumos Yoga & Barre / Photograph by Gabriela Barrantes

Stretching is a crucial, but often overlooked, part of our daily routines, whether we’re long-distance runners or simply always on the go. (So much so that we get ourselves into a bind and can’t work out the kinks on our own.) Throughout the region you’ll find franchises of StretchLab and Stretch Zone — both of which we love — but we also recommend turning to these local wellness studios for that sweet release from head to toe.

Massage Studio of Philadelphia

At her Old City boutique, founder and owner Laura Jenkins provides a two-in-one solution: part assisted stretching done on a large yoga mat, part bodywork on a table in the massage room. The sessions can be 60, 90, or 120 minutes. Jenkins says the stretch portion allows the practitioner to evaluate your range of motion and areas of tension before further releasing those areas with soft-tissue work. “A lot of our clients use this as part of their maintenance plan, while others use it for rehab purposes for acute or chronic pain management,” she says. From $140; 219 Cuthbert Street, #403, Old City.

The airy space at Massage Studio of Philadelphia / Photograph by Daniel Knoll

Lumos Yoga & Barre

Find a twice-weekly Community Stretch & Restore class at Lumos’s Green Street location. Taught in the barre room, the sessions are meant to alleviate stiffness in your body, using props like blocks, bolsters, straps, and bands for support and slower, gentle movements (no dynamic stretching here!) with longer holds. (Props give attendees different options so they can achieve stretches without having to strain or move in an uncomfortable way.) The hour-long classes take place on Mondays and Wednesdays at 7:30 p.m. $10; 2001 Green Street, Spring Garden.

A hamstring stretch / Photograph by Daniel Knoll

Svargá

Owner Klaudia Rzotkiewicz is certified in the functional training practice known as Greatest of All Time Actions (GOATA), which focuses on restoring and correcting movement patterns through biomechanics. “The exercises are designed to provide a stable foundation for your body to maintain vitality in the years to come,” she says. She also specializes in realigning your posture and pain management techniques via what she calls “ancient wellness with a modern twist.” Her bodywork session includes a phone consult to discuss your concerns and goals, a general range-of-motion assessment in her Roxborough studio with a full-body assisted stretch on a massage table, and trigger-point therapy to further relieve aching muscles and joints. Cupping, gua sha massage, and Pilates are also on offer. Bodywork sessions from $123; 7928 Ridge Avenue, #105, Roxborough.

Klaudia Rzotkiewicz of Svargá works on a patient. / Photograph by Louie Herman

Soul Healn Wellness Center

Think karaoke is just for nights out at the bar with your best pals? Think again. Soul Healn in Manayunk has a Stretch and Karaoke class that seeks to release tightness in your body through singing — along with muscle lengthening and relaxation exercises. It’s all part of owner Kishna Celce’s work to heal her clients holistically, through spiritual expansion as well as physical movement. (She opened the center three years ago to create a safe space for those recovering from emotional duress, trauma, and anxiety.) Not into singing? The Soul StretchN session uses trauma-informed stretches, such as reclined neck release and figure four, to soothe your body and mind as well as improve flexibility and circulation. Sessions from $45; 106 Gay Street, Suite 302, Manayunk.

Published as “Loosen Up” in the 2026 issue of Be Well Philly.

Lane Johnson’s Season of Strong Mental Health: Commanding Compassion

The two-time Super Bowl champ reflects on the meaningful work the Eagles’ latest opponent tackled this fall

Youth Sports in Philadelphia Are Uneven — and the Gaps Are Growing

Field at Vare Recreation Center / Photography by Gene Smirnov

It is a warm September evening at the sparkling new $21 million Vare Recreation Center at 26th and Moore streets, home to the Sigma Sharks youth sports program. Neighborhood children romp around a sprawling playground as a DJ spins oldies, while three different football teams practice in different corners of the center’s multipurpose football/ soccer field. As teams of various ages run plays, younger siblings — the next generation of Sharks — dart about.

Before the new gridiron opened in late July, the six Sigma Sharks teams practiced and played as they always had, on an unkempt grass field strewn with rocks and dotted with large dirt patches and the occasional pile of dog feces. “It was dirty, and looked like it wasn’t taken care of,” says Caleb Williams, a member of the Sharks U13 (under-13) team and an eighth-grader at Christopher Columbus Charter School.

Not anymore. The new Vare field is a pristine vivid green, surrounded by a four-foot-wide bright blue border. “We call it the water,” says Tariq “Coach T” Long, who directs the U8 squad. “Once you cross the water, you’re in with the Sharks.”

And that’s a pretty good place to be these days. The Sigma Sharks, who have been around since 1992, sponsor the football teams plus a cheerleading program and four basketball squads, serving more than 300 kids. Sharks president Anthony Meadows says they love the new facility, which also boasts two gleaming indoor basketball courts. “When the kids saw it for the first time, they lost their minds,” says Kevin Mathis, a coach since 1997. (He calls himself “the longest-tenured Shark.”)

Since Vare can’t accommodate all six teams at once, some still practice and play at Smith Playground at 24th and Jackson. Meadows calls it “adequate.” Tanisha Perry, who brings her eight-year-old twin sons from West Philly to play, disagrees. Smith is dirty, she says, and “attracts the wrong crowd.” Vare, on the other hand, is safe, with clean bathrooms and omnipresent staff members.

“I want to be here, always,” she says.

You can see why. In Philly, Vare is a unicorn of a facility that materialized through a combination of funding from the city’s soda tax and a relentless champion in the form of City Council President Kenyatta Johnson. Johnson worked with former Philadelphia Eagle Connor Barwin’s Make the World Better Foundation on the project, which is in his district.

Most city districts (and rec centers, and kids) aren’t quite this lucky. A 2023 study by Temple University, commissioned by Philadelphia Parks and Recreation and managed by the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative (a nonprofit consortium of youth sports providers and advocates that provides resources, support, and funding), looked at more than 1,400 sports facilities managed by Parks and Rec. Sixty percent of them were rated below or far below average. Eighty percent of athletic fields the kids play on aren’t stand-alone fields, but the outfields of baseball diamonds. On top of that, the Temple study found, facilities in neighborhoods with a larger percentage of white residents were of a higher quality.

It’s very much a two-tiered system. There’s a big gap between them.” — Beth Devine, executive director of the Philadelphia Youth Sports Collaborative

Zoom out a little more, though, and you see that that depressing inequity pales in comparison to the big and growing gulf between the youth sports climate in the city and that in many suburbs, where the fields, facilities, and infrastructure are … well, an entirely different ballpark. “In the suburbs, it’s not even a second thought,” says Meadows. “Kids just go to the fields and throw the ball around. Even if it’s a grass field, it’s nice. In the city, you get overused grass and dirt. And the turf fields are often locked up.”

“It’s very much a two-tiered system,” says Beth Devine, executive director of the PYSC. “There’s a big gap between them.”

She’s right about this … and then some. By now, we all know that youth sports as a whole are only getting more professionalized and more expensive as time rolls on, and that money is a real — and quickly expanding — fault line in and barrier to the world of kids athletics. (A July New York Times story about this very topic cited an Aspen Institute finding that the average U.S. sports family spent $1,016 on its child’s primary sport in 2024 — a 46 percent hike since 2019.) And the stakes of access to athletics are even higher than you might think — and affect more people than just kids and their families. Studies indicate that kids who play sports are better at problem-solving and self-regulation, and, as the Temple report showed, violent crime rates drop in neighborhoods that have youth sports facilities. The better the condition a field or court is in, Devine says, the less crime there is around it — across all types of neighborhoods.

Currently, only 25 percent of kids from U.S. households with annual incomes below $25,000 participate in youth sports, compared to 44 percent of kids from families with annual incomes greater than $100,000 — which makes it tough for sports to be any kind of great equalizer. Add to that the billionaires and private equity firms trying to get a piece of America’s $40 billion youth sports business, founding commercialized camps and leagues and tournaments that compete with and pull talent from even the most moneyed, polished suburban rec teams. All of which means that the chasm between the typical city neighborhood rec team and everyone else is only growing.

The statistics — and what they portend — can be overwhelming. It doesn’t seem like that’s going to change anytime soon.

But then … there’s Vare. Not as fancy as some of the more elite facilities you can find in the ’burbs, with a program not as structured or rigorous or polished — but a game-changer for the kids who play there. “A facility in their neighborhood that kids can call home,” as Meadows says.

“I want this to be normal for everybody,” he adds.

Which makes you think: In a city that loves and understands the value of its sports as well as Philly does — a city that produced Dawn Staley, Wilt Chamberlain, Mo’ne Davis; a city with rec teams that are out there winning championships and tournaments; a city with five (soon six) professional teams — why can’t it be the norm for everybody? Or maybe the more apt question right now, as we stare down a year that’s going to bring the world to our stoop to watch the World Cup, a PGA championship, the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, and the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, is this: How might we make it so, before the opportunity gaps — for the kids, for our city — yawn into infinity?

For eight years, Amos Huron has led the Philadelphia Youth Organization, which was founded in 1990 and encompasses the Anderson Monarchs program and its soccer, baseball, softball, and basketball teams. He believes the baseball/softball field at the Marian Anderson Rec Center — which the Monarchs also use as a multi- purpose field — is “probably the best in the city.” He’s likely right: When you walk by the field at 18th and Fitzwater, it’s hard to miss the gleaming, pristine outfield, complete with a warning track and bright yellow foul poles. The 3.4-acre facility also boasts basketball courts inside and out, and room for boxing and martial arts. There’s even an indoor baseball training facility, thanks to an assist from former Phillies star Ryan Howard a decade ago.

It’s still not close to many of its suburban counterparts.

Some 20 miles away, the 725 kids of the Newtown-Edgmont Little League play on seven grass diamonds, three of which have lights. The 15-year-old, 10,000-square-foot indoor Flanigan Center, part of the complex, was recently renovated and allows for winter workouts for NELL players and high school teams from the city and suburbs. An army of volunteers, unpaid coaches, and parents help keep the place running, as do local business sponsors: Levels range from $500 a year (Field Level Sponsor) up to $1,500 (Elite Level Sponsor, which comes with a large sign in the Flanigan Center and two baseball field signs). Even the snack bar is top-tier. “Some people eat there versus the local pizza place,” says coach and former president Daren Grande.

Not far from the NELL baseball universe, the Radnor-Wayne Little League, which will turn 75 in 2027, operates “at least” 12 fields that it leases from Radnor Township and its school district and serves between 900 and 1,000 kids in its baseball and growing softball leagues, according to president Tom McWilliams. Worth noting is that registration fees aren’t much different from a lot of what you see with leagues in the city. Those vary, but seem to hang between $100 and $250; Radnor-Wayne’s fees sit between $150 and $195, and NELL’s is $200.

On paper, Philly has far more assets than either of these townships, with 259 different city locations encompassing more than 1,500 fields and courts. But with all the kids across the city who play on one team or another (some 40 to 45 percent of Philly youth participate in “some structured activity program,” says Philly Parks and Rec director of youth sports Mike Barsotti), it’s not enough to meet the demand. In fact, access is the first problem many leagues face: Competition from adult leagues, travel outfits, high school teams — St. Joe’s Prep’s football squad has practiced on the Philly Blackhawks Athletic Club field in North Philly; Universal Audenried Charter High School practices at Vare — and other neighborhood programs creates scheduling and permitting challenges. The city’s permit process favors neighborhood organizations, but if they don’t register in time, other groups get the chance to sign up (and they’re usually more organized and quicker to fill out requests, says Barsotti). And when new fields open, they reach capacity almost immediately. At the South Philadelphia Super Site turf football field at 10th and Bigler, games are scheduled to the minute during the season, says Adam Douberly, a father to three rec-league athletes. Kids get one hour, exactly, on the fields, playing times vary, and games can end as late as 10 p.m.

Even the popular 1,200-player Philadelphia Dragons Sports Association (formerly the Taney Youth Baseball Association, home to the team that played in the 2014 Little League World Series), which recent president John Maher says has “a relatively affluent demographic, mostly in Center City,” can’t find sufficient field space, and “100 percent” has facility envy when it faces suburban teams in District 19 Little League competition. (Right now the Dragons’ biggest challenge, he says, is finding fields for its burgeoning coed flag football program.)

All of this use (and overuse) helps lead to the second big issue: maintenance. “The city budget to maintain the fields is close to zero, so the fields may start off with grass, but at the end of the season, they are dirt pits,” says Liam Connolly, executive director of Safe-Hub Philadelphia, which provides soccer opportunities for kids ages four to 18 in the Kensington area.

Douberly’s boys play in the Dragons program, which plays at FDR Park and Markward Playground in Schuylkill River Park, among other spots. Markward, he says, “is completely overgrown. It’s like bouncing a baseball on a concrete floor.” Playing on fields of that caliber, especially for those who know there is something better out there, isn’t just harder. It’s dispiriting.

City fields in disrepair at Markward Playground

“The kids would go to other places and see all of [the nice facilities] when their field was dust and rocks,” Meadows says about the Sharks, pre–Vare glow-up.

Curt De Veaux, a Monarchs coach who also runs the City Athletics soccer program with his wife, Janea, is trying to introduce soccer to kids across Philly. He agrees that it’s hard to find places to play. And at Germantown’s Mallery Rec Center, where he directs City Athletics, “I’ve personally paid to get the grass cut and lines put on our field,” he says. (Barsotti, who notes that the department’s mowing contract is upwards of $3 million a year, says cuts are scheduled weekly during the seasons: “Some groups choose to mow more frequently to keep the grass the length they want and ensure it’s cut fresh for their games.”)

It’s not just the field and facility quality teams grapple with, either: A third issue is that the lack of infrastructure and financial resources within grassroots organizations means, across all kinds of teams, that there’s often not much room for strategic planning or coach training, or the ability to travel to seminars and conferences that provide information on new leadership techniques.

De Veaux would say that his goals for City Athletics are even more modest than that: He mostly wants to grow his reach across the city, to get more kids acquainted with the basics so they can grow into players who love the sport and can compete if they want. When it comes to competition, he knows what’s out there. As a longtime coach, he’s spent time in the past meeting with members of the suburban soccer powerhouse FC Delco — a regional force and travel league that plays a national schedule and includes many of the best players from the area — to learn more about how to run a high-end program.

FC Delco, which started in the 1980s in Delaware County, now has main hubs in Downingtown and Conshohocken with about 10 fields between them, plus more than 60 paid, certified coaches and some 1,700 boys and girls on 112 teams. Many of its players are from the suburbs, but some city kids make the trek, general manager Rob Elliot says. Money is another potential barrier for kids. Travel costs for the teams can run into the thousands each year, though the club does provide some financial aid and partners with the JT Dorsey Foundation, which offers soccer opportunities for kids in impoverished areas across Pennsylvania.

De Veaux, meanwhile, says his meager resources allow for only limited growth. And overall lack of infrastructure and resources in local and grassroots organizations just “widens that gap,” as he says, between those teams and the FC Delcos of the world. And the bigger that gap gets, the worry goes, the more kids and families are likely to opt out of city programs like his. Or just opt out of sports entirely.

At a time in the 1980s and 1990s when youth sports were on the rise, Philadelphia’s dire city budget shortfalls left no room for investment in recreational spaces, while in townships and neighborhoods outside the city, programs grew and thrived. Still today, many of the surrounding towns have real funding advantages, even as most leagues receive no money from the townships in which they’re based. They exist (and in some cases, excel) thanks to registration fees, donations, and sponsorships. Media Little League president Andrew Tamaccio says that league “has 100 local sponsors, if not more.” Marple Township Little League, with 360 kids, has a slew of sponsors too, and significant community support that helps keep the fields mowed, the lines chalked, and the snack bar stocked.

While it’s true that leagues in less moneyed townships face many of the same issues as their city counterparts, by and large, the differences between the suburbs and the city — between leagues with cash and those without — are real, and the gap is wide, the Sharks’ Meadows says. Though that doesn’t mean there isn’t real talent in the city rec leagues, and real successes. The Blackhawks in North Philly have won five national gridiron titles, the Sharks have won “several championships,” Meadows says, and the Frankford Chargers U8 football team captured a 2024 national title.

But competition is getting stiffer on and off the field.

As the July Times story detailed, the expense and expectations of youth sports are on a steady rise: expense in the form of ever more elite travel teams, gear, camps, and tournaments; expectations in the sense that parents increasingly are looking for returns on their (significant) investments in the form of college scholarships. Not exactly a sure bet, when you consider that the odds of a high school player even making a Division I hoops roster are 110:1, according to data from the NCAA. It’s 108:1 for soccer, 43:1 for baseball, and 33:1 for football.

Meanwhile, PYSC’s Devine frets, the abundance of travel teams and the overall shift we’re seeing toward ever more elite athletic experiences “has sucked the life out of youth and rec-league programs.”

It was in this sports climate and moment that board members of three different city soccer organizations — Fairmount, Philadelphia City FC (formerly Palumbo), and United Philly — decided to rally. In February of 2025, they voted to combine and form the Philadelphia International FC (known as Inter Philly) in hopes of replicating something like the FC Delco model.

“We want to provide people who live in the city with a competitive environment similar to what is available in the suburbs,” says Connor Robick, the group’s co- executive director. They currently work with nearly 4,000 kids (about 850 players on 53 travel squads, the rest in recreational play), ages two to 19, all over the city, from introductory training (which starts at $140 for an eight-week program) to highly competitive travel squads (which can run between $1,650 and $2,100). It has home fields at the Edgely Fields in Fairmount Park, Cristo Rey Philadelphia High School and the Salvation Army Kroc Center in North Philly, and the South Philly Super Site and Palumbo.

As with many of the suburban and travel teams, Inter Philly fundraises with and seeks sponsorships from local businesses to offer up to $300,000 annually in financial aid to its team members. Of course, Robick says, the organization is always looking to raise more cash and do more.

Other city programs and rec leagues have similar funding aims and challenges. “I beat the bushes to find money,” Meadows says of his efforts in South Philadelphia.

South Philly Sigma Sharks president Anthony Meadows

There’s also been a continuous push by Barsotti and other city parks officials, as well as community members, to increase rec center staff so that there are enough people to help with programs “from sports to arts to after-school,” Barsotti says. But it’s hard finding — and paying — enough qualified people. When suburban soccer clubs are paying U9 coaches $65 an hour, he says, it’s tough — nay, impossible — for the city to match it. It’s often up to the community to provide volunteers to make things run smoothly, another hard task.

You might be thinking now: What about the Philadelphia Beverage Tax, aka the soda tax? Wasn’t that supposed to help chip away at this very thing? Mayor Jim Kenney’s nine-year-old tax has actually brought in nearly $600 million in revenues. Nearly 40 percent of that money has gone — as planned — to fund operating expenses and the city’s also crucial preschool expansion, while money earmarked to revamp and renovate parks, libraries, and rec centers (the Rebuild initiative) doesn’t extend to the operations of those places.

Still, there has been progress in improving facilities and fields. Vare, for one example. As of press time, 39 sites have seen a revamp at some level — new turf fields at Murphy Recreation Center in South Philly, a freshly sodded football field at Chew Playground in Point Breeze, upgraded basketball courts at 8th and Diamond Playground in North Philly. Another 14 are under or preparing for construction right now.

It’s also worth noting that revenues from the tax have fallen short of the $92 million-per-year projection (the 2023 total was $72.7 million). Even so, this year, Barsotti says, youth sports did manage to get a bit of an unexpected windfall in the form of an extra $3 million in the budget for fiscal year 2025. The cash went into equipment (basketballs, soccer balls, portable scoreboards, volleyball poles), coach training through a program with PYSC, and grants for community sports organizations. It might be a small sign of better times to come; in the run-up to her election, Mayor Cherelle Parker said she’d like to at least double the Parks and Rec budget by the end of her first term (to help catch up from those budget shortfalls of the ’80s and ’90s). This would surely help get more playing spaces up to snuff, though the actual numbers still don’t inspire a huge amount of optimism when you compare them to those in other cities. Chicago’s 2025 budget included $598 million for parks and rec; New York’s was $582.9 million. Dallas’s 2026 budget has $118.4 million slated for the parks department, and in Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser’s most recent budget included $89 million just for an indoor training facility for boxers, runners, gymnasts, and even e-sports players. In Philly, the entire Parks and Rec budget is $83.4 million.

It seems clear, in other words, that if we want to level up on our youth sports, it’s going to take more than just what the city coffers have to offer. It’s time we all look elsewhere — lots of elsewheres — for creative solutions.

It was the night of the “Battle of the Beach” game — La Salle College High School versus Malvern Prep in Ocean City. Enon Eagles athletic director Greg K. Burris couldn’t make it to the Shore — he was running his own football practice in North Philly. But he streamed the game live, beaming the whole time. La Salle’s dramatic 42–35 victory was due in part to three Enon Eagles alumni who all scored touchdowns, as well as “a couple of guys on defense wreaking havoc.”

“I was sitting there with my chest puffed out,” Burris says.

The Eagles are a refreshing end run in the world of Philly youth sports, part of the 149-year-old Germantown-based Enon Tabernacle Baptist Church, which has more than 5,000 members at its two locations. The church’s athletic program is a little more than 20 years old — a model that ought to be studied, scaled, and replicated. The program includes baseball, basketball, football, soccer, track and field, cheerleading, martial arts, and tennis opportunities — all part of the “athletic ministry” at the church. Participating families (including non-Christians; the teams take all comers) aren’t obligated to attend services or be members, but there is Bible study offered after practices and games. “We are a church,” Burris says. “We don’t hide that.”

The 700-plus kids in the Eagles program play against other neighborhood programs, and Enon offers reasonable registration fees (they vary depending on the sport; in some cases there’s no fee), handles upkeep on the facilities they use — including a turf field — and mitigates equipment and travel costs through offerings and tithing from church members. Their programs run year-round and attract families from all over the city. Volunteer coaches direct the teams, and parents help out with day-to-day operations.

As the Eagles soar, there’s more hope — and more ideas — to be found, as the city does what it can, little by little. There’s Vare, of course, and other crucial rec center improvements in progress at Johnny Sample Recreation Center in Cobbs Creek Park, which will feature new indoor basketball courts and a pool. There’s also FDR Park, which will soon welcome a facilities bonanza, thanks to money from the city and state, grants from entities like the William Penn Foundation, and contributions from outside organizations like the Reinvestment Fund.

When, a few years back, the Fairmount Park Conservancy surveyed 3,000 South Philadelphians, they learned that more basketball courts ranked first on the collective wish list for FDR Park. Another priority was athletic fields. And so that’s what’s in the works (albeit the very slow works): 12 new multipurpose fields, a baseball/softball cloverleaf, and eight new courts. (Five multipurpose fields will debut in 2026, according to Conservancy chief operations and project officer Allison Schapker; they’ll be available via permits to teams and programs from all over the city.)

Inter Philly’s Robick is optimistic about what the FDR development means for kids sports. “It will be a crown jewel of the city,” he says. “It’s easy to get there. There will be cork pellets on the turf fields that are non-cancer-causing. And people can use it from 5 a.m. to 1 a.m. if they want to.”

Football at Vare

Another initiative worth getting excited about? The $36 million Alan Horwitz “Sixth Man” Center in Nicetown, home to the 10-year-old Philadelphia Youth Basketball enterprise. The place opened in the summer of 2024, the result of a $5 million gift from namesake Horwitz (founder of Campus Apartments and Sixers superfan) and then a multi-year campaign from the PYB that gathered a number of investors and contributors who bought commemorative bricks in the building for $250 each. A combination of that funding plus donations from private citizens and foundations, grants, city and state money, and revenue from renting the building to AAU basketball teams and other groups has brought the 100,000-square-foot facility to life.

Today, PYB offers athletic competition and training there, along with a variety of off-court enrichment programs for some 1,600 kids and teens. Previously, PYB held practices, games, and after-school activities at middle schools in North and Northwest Philadelphia. Now, the Horwitz Center is the hub, and the organization has expanded its reach to 24 middle schools, says PYB chief mission officer Ameen Akbar.

“Basketball is the carrot,” he says. “It’s how I grew up and a lot of us grew up in Philadelphia. That is the avenue we use to connect kids with quality coach-mentors and solid adults in the area. Then, we introduce them to the developmental programs.”

Like the Enon Eagles, PYB offers a good program and a great model. Like Vare and eventually like FDR, it offers a place to play that reflects the worth of our youth sports. Of our youth themselves. We could use many more.

In a city with a Chamber of Commerce that knows good and well the benefits of having families rooted and happy here; with the immense reach and vision of Comcast and Comcast Spectacor; with the talent and cash of the Sixers and the Flyers and the forthcoming WNBA team; with the heart and heft of two world-champion pro teams, each with its own stadium (and a new one maybe in the offing); and with our universities, rife with sports and with young talent itching for work experience, what other viable models of support might exist? How many rec centers could be adopted? How many more teams could get coaching help? Or lighting for their fields? Or new fencing? How many 10-year corporate commitments to paying for field upkeep or uniform donation or training programs for community members might make a difference to countless children and neighborhoods?

The World Cup is coming to town in a handful of months, with some $770 million in economic impact, reports suggest. How about taking a hefty sliver of the tax money coming in and using it to bolster Inter Philly and other soccer initiatives? Major League Baseball will likely throw a few million toward youth sports this summer when Philadelphia hosts the All-Star Game, as it did in 2025 in Atlanta. Now is the time to figure out how to find matching donors, how to use that money to roll into bigger public-private partnerships, how to invest in something more lasting than patching up our fields for a season. Now is the time to understand what is at stake in this moment, to proceed with intention. Ahead of the massive sports year that will be 2026 in Philadelphia, why not appoint a youth sports czar, Mayor Parker?

The overwhelming benefits of citywide youth sports programs and more facilities to host them — like Vare, like Marian Anderson — will help the next generations build a sturdier, safer, stronger urban fabric. It will also create that now, in real time. It will boost our neighborhoods. “We’ve seen the community embrace us,” the Sharks’ Mathis says. And obviously, as he notes, it also makes a difference to our young people, who have an outlet and a place they can claim — and come into — as their own. Something every kid deserves.

Published as “Leveling the Field” in the December 2025/January 2026 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Can This New Food Hall Solve College Hunger?

University City’s Gather stands alone for its commitment to community, small local restaurants and fighting hunger — though you can just go for the tasty food