If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Jawdropper of the Week: Colonial Pleasure Palace in Upper Makefield

This stone house at 9 Hayhurst Dr., Newtown, PA 18940 has that authentic 18th-century style so many prize in Bucks County country houses. But it’s just one piece of a several-building compound designed for modern living, entertaining and even recreation. / Bright MLS images via BHHS Fox & Roach Realtors

I don’t know whether it’s the influence of New Hope, or the rolling countryside, or the abundance of raw materials, but Bucks County has this way of attracting people who love to play and entertain.

The current owner of Egypt Farm, this Upper Makefield country estate house for sale, is clearly one of those people, as you will soon learn.

This nearly 38-acre rural retreat dates to 1729. That’s when the stone house you see at the top was built.

Aerial vies of compound: main house and garage at left, pool to its right, barn and mock covered bridge next to the pool, fire pit and carriage house beyond those

And an aerial view of Egypt Farm’s central compound today should make clear that this was once an actual farm.

You could make it one again, but that would require adding things like a new barn to it, for the one that’s there now serves as a combination guest house and classic Bucks County party barn.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s take a look at the main house first.

Living room

Living room

It has many of the hallmarks of a 1729 house but has been updated to accommodate modern living. The rear entrance opens onto a large living room with two fireplaces.

Den

Another one all but fills this den. Colonial history buffs will recognize it as a kitchen hearth fireplace. The listing agent says it’s believed to be one of the largest surviving Colonial fireplaces in Bucks County.

Front porch

A Dutch door leads to the front porch from this room, which also contains a wine bar with a beer tap. If you wanted to, you could turn this into a distinctive formal dining room. And if that hearth fireplace still works — and it appears to — you could throw a truly unique party by feeding your guests the way an 18th-century family would. I’m sure there are people at Historic RittenhouseTown in the city who could show you how.

Kitchen

Kitchen and dining area

However, you’re more likely to feed them food prepared in the totally modern yet historically sensitive eat-in kitchen.

Primary bedroom

Past and prsent also meet in the primary bedroom suite upstairs. The bedroom itself looks much as it might have in the 1700s — once you factor out the electric lamps and modern rug, that is.

Primary bathroom

But the bathroom clearly reflects modern desires even as it respects the past. It has a steam shower, dual vanities, a soaking tub and a mirror TV. None of these would have existed in their present form (or at all) in 1729.

Five other bedrooms and three bathrooms also occupy the two upper floors.

Guest house/party barn

You will find two more bedrooms plus two full and two half baths in the barn, which architect Joel Petty transformed into what you see here.

Great room

Of course, it has a great room that preserves the barn ambience while offering modern style and comfort.

Great room

It has both a balcony overlook and a retractable movie screen over its main fireplace.

Dining room

Kitchen

The barn already has a formal dining room and a kitchen equipped to produce great meals for those dining in it.

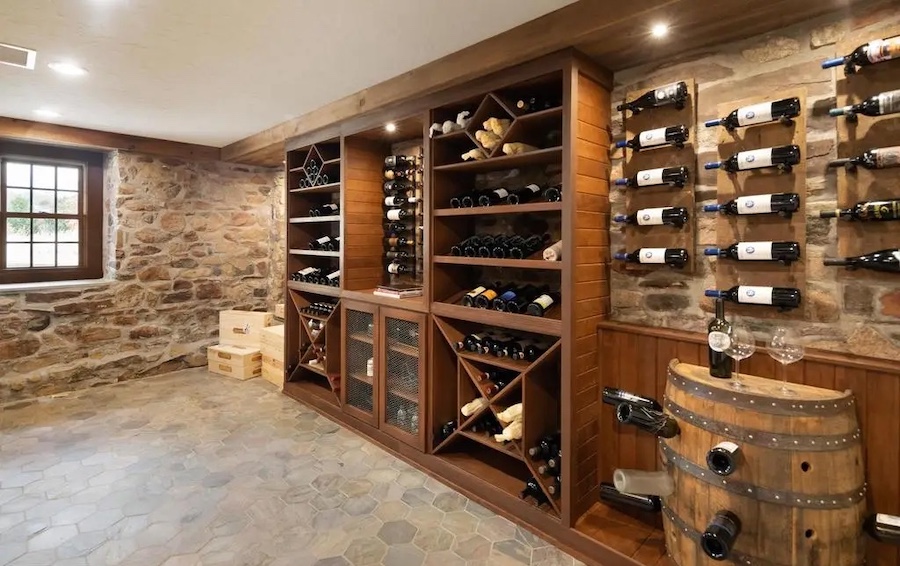

Wine cellar

It also has a wine cellar and tasting room.

Game room

The second floor boasts a game room with what I could only call a man-cave chandelier over its bar. The barn also has a striking spiral staircase and an elevator serving all floors.

Golf simulator

Resistance pool

And it has features to please your inner jock: a golf simulator off the great room, a Swimex resistance pool and a sauna.

You should have copped wise by now to the fact that this place was designed for entertaining. But I’m not done showing off its entertaining spaces yet.

Pool, spa and fire pit

Behind the barn you will find a saltwater pool with a Jacuzzi spa and a fire pit.

Carriage house dining area

Past the fire pit, a carriage house has an outdoor dining area under its arbor.

Carriage house party room

Custom beer keg tap in party room

Inside, it has a spacious room whose bar has a custom beer-keg tap. The listing agent says you could put a Ping-Pong table here, I say get a folding one so you can move it out of the way and hold a dance party here. (If disco is your thing, the cathedral ceiling can easily accommodate a mirrored ball. And pardon my channeling New Hope, but that means you could show your guests a gay old time here.)

All of this takes up only a small piece of Egypt Farm’s 37.9 acres. And that means you have room to add more outdoor amenities. Tennis, anyone? How about an actual golf hole or two, or a driving range? Or you could build that second barn, outfit it with stables, and make this an equestrian farm. If you’d like to grow your own food, there’s room for that as well.

Add those and you’d have the best retreat in Bucks with this Upper Makefield country estate house for sale. Even without them, Egypt Farm is already a strong contender for that title.

THE FINE PRINT

Main House

BEDS: 6

BATHS: 4 full, 1 half

SQUARE FEET: 4,100

Guest House/Party Barn

BEDS: 2

BATHS: 2 full, 1 half

SQUARE FEET: 7,000-plus

SALE PRICE: $4,975,000

9 Hayhurst Dr., Newtown, PA 18940 [Lorraine Eastman | BHHS Fox & Roach Realtors]

Thanksgiving Tips from Philly Chefs

Tired of the same old turkey? Get some Thanksgiving tips, tricks and recipes from our favorite Philadelphia chefs. (Getty Images)

Want to know how to tell if your turkey is actually done? (Don’t trust that pop-up thing!) Not sure if you’re supposed to take that bag containing the weird looking stuff out of the cavity before putting your bird in the oven? (You are.) For queries like these, there’s the tried-and-true Butterball Turkey Talk-Line, 1-800-BUTTERBALL. But if you want advice from some of our favorite Philly food people on how to spark new life into America’s biggest food holiday and not go totally bonkers in the process, you’ve come to the right place. Happy Thanksgiving!

Jose Garces On Deep-Fried Turkey

I’ve been frying my turkeys for a long, long time. It’s a tricky thing. And it’s kind of dangerous. But it’s also the most simple and effective way to do it. The end product is great. And it’s fast. For a 20-pound bird, I fry it for 45 minutes to an hour. And by frying the turkey, the oven is freed up. When you’re entertaining, the hardest thing is to get all of your sides hot. This solves that problem. Jose Garces is chief culinary officer of Garces Group.

Ellen Yin On Turkey Being Overrated

Turkey was never a big thing in our house. It was always just symbolic. My mother used to stuff a chicken with rice and Chinese sausage and braise it in soy sauce. People will eat turkey. But what people really want are the fixings. Ellen Yin is the owner of Fork, A.Kitchen, and High Street Market.

Jennifer Zavala On Gift-Giving

If you’re going to someone’s house for Thanksgiving, you absolutely need to bring a gift, whether that’s a bottle of wine or a joint. You can also bring some pre-made items from a small, local business. These are great conversation starters. Go to Isgro’s and get cannoli. They’ve been making those cannoli for 120 years! Bring them and tell all the guest the Isgro’s story. Jennifer Zavala is the owner of Juana Tamale.

Joe Cicala On Turkey Soup Recipes

In the Abruzzo region, they use a lot of turkey for Christmas. And there are wild turkeys running all over the place. They have a turkey soup recipe with escarole, stracciatella style. They mix an egg with pecorino and black pepper and use that as the protein. It’s kind of like egg drop soup. And then with all of the cooked meat, they pick it off and make a turkey salad as a secundo. They dress it with pomegranate seeds. The seeds are tart and sweet and take away some of the gaminess. I sprinkle my roasted turkey with pomegranate seeds. They’re in season. Joe Cicala is the executive chef and owner of Cicala at the Divine Lorraine and Sorellina.

Keith Taylor On Planning Ahead

Do as little cooking as possible on the day of Thanksgiving. Make a list of everything you are going to make. And start early. There’s no reason you should be baking pies on Thanksgiving Day. Pies are the last thing you eat and the first thing you make. They hold beautifully. And with turkey, do a lazy man’s turkey. A day or two before Thanksgiving, roast a whole brined turkey and then cool it down to 40 degrees. Then deconstruct it. Slice down the breast meat. Take off all the dark meat. And refrigerate the whole thing. Forty minutes before it’s time to eat, put the turkey in the oven, covered with wet paper towel and then foil. Roast it for 40 minutes at 400 degrees. And that’s it. Doing things like this will take so much stress out of Thanksgiving Day. You can sit back and listen to some beautiful R&B. Keith Taylor is the owner of Zachary’s BBQ Soul Kitchen & Catering.

Jennifer Carroll On the Perks of Being Efficient

Clean out and organize your fridge before you go shopping for ingredients. This ensures you have enough room to properly store things. Make a shopping list and prep list. This will make you more efficient and focused. Clean while you cook so you don’t have a major mess at the end of cooking. Read your recipes from top to bottom before you start cooking it. Jennifer Carroll was featured on Bravo’s Top Chef and is the owner of the experiential dining company Carroll Couture Cuisine.

Rich Landau On Color In Your Thanksgiving Recipes

Most Thanksgiving food tends to be brown. Bubbling brown gravies. The stuffing. I always think of it as ugly food. We try to bring in colorful squashes. And the green vegetables that we do use, we don’t cook them to death. We also believe in the centerpiece, even at a vegetarian Thanksgiving. Many vegetarians just do the side dishes. But psychologically, we all grew up with this giant carcass as a centerpiece. So we might do a giant roasted squash, a whole roasted eggplant, or giant portabellas with gravy in the center of the table. The key for us is color and variety. Rich Landau is chef and owner of Vedge and Ground Provisions.

Marc Vetri On Why You Should Never Roast a Whole Turkey

I’ve never roasted a whole turkey with the stuffing and all that. I’m just not into it. I like to break it up and do different things with it. This year, I take the breasts, leaving them on the bone and smoking them. The thighs and legs, I’ll debone and then I’ll salt it for three to four hours. Then I kind of hammer it out and cook it between two sheet pans in the oven until it’s almost finished. After that, I’ll let them cool down and then stick them on the grill. And then I’ll use another turkey for turkey sausage and I’ll make a turkey sausage pizza. I like to have fun, mix and match. Marc Vetri is the chef and owner of Vetri Cucina.

Bryan Sikora On Avoiding Excess

Don’t overdo it. Everybody ends up with too much food, spending too much money, and too much time on Thanksgiving. Leftovers are nice. But there are really only a couple of things that people actually want. You don’t have to go out and spend $500 to feed 8 people, with most of the food going to waste. You can be more focused on doing things right, buying the right wines. Because when it comes down to it, less really is more. And you always wind up with more no matter what. I don’t think anyone has ever run out food on Thanksgiving. Bryan Sikora is the owner of Noble Goat, La Fia, Merchant Bar, Crow Bar, and Heath Kitchen in Wilmington and Chester County.

[Ed. Note: Some of these tips appeared in a previous version of this story.]

All the End-of-Year Restaurant Openings You Need to Know About

Loretta’s bagel sandwich / Photograph courtesy of Loretta’s

Howdy, buckaroos! And welcome back to the weekly Foobooz food news round-up. I know it’s Thanksgiving week, and a lot of you out there have more important things to worry about than who has a new restaurant opening (Liz Grothe, Jesse Ito, Lauren Biederman, and others), who has a seven-chef collaboration dinner coming up (Cantina La Martina), or where to get a killer new cheesesteak (Reading Terminal Market). So let’s just keep this brief so we can all get back to brining the turkey, untangling the Christmas lights, resenting our in-laws, watching Home For The Holidays for the 100th time, or whatever else it is you do to make it over this first hurdle of the holiday season. We’ll kick things off this week with this …

Wait, What Do You Mean Jesse, Liz, Lauren (and Others) Have New Restaurants Opening?

Yeah, last week was a big week for opening announcements. Everyone wanted to get it out of the way before their momentous news got lost in the hubbub of theme dinners, office parties, and holiday bar crawls. So we had details from several big operators that we covered right here on Le ‘Booz, but all of them are worth mentioning again, just in case you missed ’em.

First, we had a wealth of details from Maddy Sweitzer-Lamme on the imminent opening of Liz Grothe’s first permanent restaurant, Scampi. After years of operating a kind of rolling, semi-private dinner party out of her apartment, after years of pop-ups and nostalgic/nerdy collaborations, Grothe announced a few months back that she’d finally picked up a permanent space and would be turning it into a restaurant celebrating both the cuisine of the Italian diaspora and whatever weird, hyper-specific obsessions with Midwestern chain restaurants or suburban comfort foods happened to be knocking around in her head. The space she picked? The old Neighborhood Ramen spot at 617 South 3rd Street in Queen Village — all of which we talked about back when I first wrote about Grothe’s big jump.

But now we know a few more things, too. Like how the menu is going to be a $115 all-inclusive prix-fixe, covering five courses, with two seatings a night — at 5:30 p.m. and 8:15 p.m. And what, exactly, she’s going to be cooking: “It’s regional Italian food with influences from everywhere Italians have gone,” Grothe told Maddy. With a spike of her own tastes and sense of humor. Think culurgiones stuffed with trout sitting in sour cream and topped with trout roe, sure. But also a classic tiramisu topped with Frosted Flakes.

And Scampi is going to be hitting the scene soon, too. Opening night is December 4th, and reservations are available right now.

Anyway, Maddy has a lot of details (including where the name came from). And you can read all about it right here.

Photograph courtesy of dancerobot

Next, I got the first details on Jesse Ito’s new restaurant, which we’re all going to have to wait a little bit longer for.

He’s calling the place dancerobot (which I love), and it’s going to be an ’80s-inspired Japanese izakaya focusing on traditional and modern Japanese bar food, Japanese-American comfort food, and brunch — which is a huge departure from the works he’s been doing for the past several years at Royal Sushi & Izakaya, but does give him the chance to make Japanese pancakes and homemade milk-bread toasts, so it’s pretty much win-win for everybody.

Dancerobot will be opening in the old Foodery space at 1710 Sansom Street with Ito’s long-time right-hand man, Justin Bacharach, leading the kitchen. The opening date is still very much up in the air, but they’re looking at spring (or maybe summer) 2025.

Up in NoLibs, Laura Swartz got to take a look at Mr. Ivy, and it is weird. I mean, cool, sure, if you’re into modernist cabaret, DJ sets, “ambient performers,” and light installations, but also a place that is leaning very hard into being as cutting-edge and provocative as possible — right down to operating on weekends only and making everyone cover up their cell phone cameras with stickers before they enter.

Still, Laura has some very Tron-meets-industrial-modernism-plus-that-one-party-scene-from-the-first-season-of-Succession (yeah, you know the one I mean) pictures from inside, plus details on the build-out and what’s going to go on there when the doors open to the public — which happened over the weekend. So check it out if you’re curious.

Finally, remember last week when I told you about the new caviar kiosk that Lauren Biederman had opened at 19th and Arch to complement the array of fancy foods she already has available at her storefront in the Italian Market? Yeah, well, that wasn’t the only new project Lauren had cooking.

She’s also got a full-on restaurant in the works. Tesiny will be an oyster bar and grill with a double bar and a cocktail program, opening in an old garage with big front windows at 719 Dickinson Street in South Philly. Biederman is hoping for an April opening.

Oh, Wait. There’s Still Some More

Cloud Cups Gelato / Photograph by Kory Aversa

Thought we were done? Nope. That’s just the places that we’ve talked about on Foobooz over the past week or so. But believe me, there’s more.

We also got word that Cloud Cups Gelato and Darnel’s Cakes had teamed up like some kind of mini-dessert Voltron to open a combined storefront at 2311 Frankford Avenue in Fishtown. This is something of a homecoming for Galen Thomas, owner of Cloud Cups, because 2311 Frankford? That’s where he had his original shop (which closed in 2022 for renovations, and so he could open his flagship store in Harrowgate).

Now, both he and Kyle Cuffie-Scott of Darnel’s are combining forces in the shop that reopened over the weekend. They’re leaning into both the season and the team-up with a “Let It Snow” vibe, offering candy cane and egg nog gelato, hot chocolate affogatos, sundaes made with Darnel’s cookies or brownies topped with gelato, cookie-gelato sandwiches dipped in sprinkles or toasted cake crumbs, and “D’s Cloud Birthday Cakes,” made with two layers of Darnel’s cake and two layers of Cloud Cups gelato, then iced, decorated, and served frozen for a wintertime birthday treat.

Speaking of desserts, it looks like Weckerley’s Ice Cream is looking to expand into Rittenhouse Square. The Business Journal is reporting that Weckerley’s current owner Cristina Torres — who took over Weckerley’s from founders Jen and Andy Satinsky in 2023 and already has locations in Fishtown and King of Prussia — has gotten approval for signage outside a space at 1600 Spruce Street but hasn’t yet completely settled on the location.

Getting signs ready? That seems like a pretty big step. So we’ll be keeping an eye on the space in the coming months to see what happens.

But if you’re looking for something with an opening date that’s a little bit closer, how ’bout this: Remember back in July when I told y’all about the folks from Bloomsday and Green Engine Coffee making plans for a “cafe and bakery offering robust sweet and savory Viennoiserie-style pastries, seasonal breakfast and lunch staples, and a specialty coffee program in Philadelphia’s Headhouse Square neighborhood?” Well, guess what? That place is called Loretta’s, and Loretta’s is ready to open the doors, and has set December 7th as their official opening day.

Ham and brie sandwich / Photograph courtesy of Loretta’s

But I’m mentioning it now because the joint is currently in soft-open mode and has been selling coffee and pastries at 410 South 2nd Street from 8 a.m. until everything sells out. And, apparently, stuff has been selling out.

In its final form, Loretta’s will be offering breakfast and lunch staples, plus pastry and coffee. We’re talking chorizo, egg, potato, and cheese hand pies, breakfast hoagies, spoon salads, meatloaf patty melts, apple galette, cinnamon buns, and homemade cosmic brownies, plus a full Green Engine-style coffee program in a 16-seat, 600-square-foot cafe in Headhouse.

Honestly, they had me at the breakfast hand pies, but I will walk a mile for a cosmic brownie, so if y’all need me, you know where to find me starting December 7th.

Okay, Last One

Amid all the other news that broke last week, I wasn’t about to let this one slip past me: Roy Rogers is opening a new store on Haddonfield Road in Cherry Hill this spring. This will be the first Roy Rogers to operate in the Philly area since the ’80s. And Victor Fiorillo already used his column space to make fun of it a little bit.

But I am NOT making fun of it. I am excited about it. Because me and Roy Rogers? We got history. My wife has an even longer love affair with a certain classic menu item from the drive-thru burger joint. And having one closer to us than the Allentown Service Plaza is absolutely something worth looking forward to in this fucked-up moment of history we find ourselves currently living through.

No matter what Victor thinks.

Now who has room for some leftovers?

The Leftovers

7 Moles spread from 2023 / Photograph courtesy of Cantina La Martina

Okay, so I know I already made one Voltron joke this week, but we’ve got two additional team-ups that are pretty Voltron-esque in the greater-than-the-sum-of-their-parts department.

First, there’s a new cheesesteak joint that just opened at the Reading Terminal Market. And while normally this wouldn’t be worth much more than a brief passing mention, this one is different because it has some serious neighborhood heavyweights behind it.

Last week, Joey Nicolosi of Tommy DiNic’s, Dave Braunstein of Pearl’s Oyster Bar, and Danny DiGiampietro of Angelo’s all got together and opened Uncle Gus’ Steaks at the RTM, in the space formerly occupied by Carmen’s Famous Italian Hoagies and Cheesesteaks. And this place is doing nothing but slinging steaks — 12-inch cheesesteaks on DiGiampietro’s homemade bread, with high-quality ingredients and produce sourced from Iovine’s. It is local, it is focused, and it is serious about its steaks.

Plus, these three guys have known each other for a long time. DiGiampietro used to run a bread route that delivered to both DiNic’s and Pearl’s at the RTM. DiGiampietro and Nicolosi grew up together in South Jersey, and Braunstein got to know DiGiampietro as a customer at his original Angelo’s in Haddonfield. Also, Dave Braunstein’s brother, Jared, manages the Angelo’s in South Philly.

Small world.

The new shop is up and running now. Hours are 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., seven days a week.

Second, over at Cantina La Martina, Dionicio Jiménez is bringing back his 7 Moles dinner for a third year, calling in seven local chefs to cook a seven-course dinner featuring seven different mole dishes. And the lineup is bonkers. Dig it: He’s got Alejandro Sánchez from Mesona, Chance Anies from Tabachoy, Jennifer Zavala from Juana Tamale, Yun Fuentes from Bolo, Ange Branca from Kampar, Eric Leveillee from Lacroix, plus chef Ed Crochet AND pastry chef Justine Macneil from Fiore, all cooking a single menu for a one-night-only riff on the classic Feast of the Seven Fishes.

And check out the menu:

Spiced charred apples, aromatic apple mole

Alejandro Sánchez

Lumpia sariwa: crepe spring roll with shrimp and vegetables, brown peanut mole

Chance Anies

Mole blanco, seared scallop, chicharron, pomegranate oil

Jennifer Zavala

Banana leaf steamed red snapper, warm ejotes salad, mole amarillo

Yun Fuentes

Babi buah keluak: pork with the illusive keluak nut mole from the mangrove forest

Ange Branca

Glazed lamb belly, chicatana mole and marigold

Eric Leveillee

Bonet with amarena cherries, amaretti cookies, Italian black mole

Ed Crochet and Justine Macneil

There’ll also be live performances, a complimentary apple, guava, and sugar cane ponche, and a gift for everyone who shows up, courtesy of Jiménez and his wife, Mariangeli Alicea Saez. Seriously, it looks like one of those events that no one will want to miss. So if you’re down, tickets are $150 a head, not counting tax, tip, or drinks. And you can get yours here.

I wouldn’t wait too long.

Finally this week, once upon a time, we used to close out our Thanksgiving week coverage on Foobooz by posting the classic 1978 “Turkeys Away” episode of WKRP in Cincinatti — one of the single greatest half-hours of television ever broadcast.

Apparently, we’re not allowed to do that anymore. And as much as that sucks, I think y’all know that I am nothing if not a man with a healthy respect for the rules. A fine and upstanding young gentleman who would never dream of running athwart John Law.

So while I’m no longer able to simply show you the video, no one can stop me from wishing you all a happy Thanksgiving in the best way I know how. Here’s to ya, Philly. And happy Turkey Day to all.

Bastia: A Mediterranean Marvel in Fishtown

From left: Tyler Akin; a plate of honeycrisp apples with Perrystead’s Atlantis cheese, lonzu, tarragon, and honey at Bastia. / Photography by Courtney Apple

There’s this scene in Ratatouille where Remy the rat is trying to show his brother (Emile, also a rat) that he can do better than eating garbage all day. Remy gives Emile a grape and a piece of cheese. He tells Emile to close his eyes. To focus on the flavors of each thing. Emile does what Remy says. He eats the cheese, then the grape, and, on screen, we see some little sparks of color to represent the experience of truly tasting something. But then he eats both together, and, for the first time ever, fireworks explode in his head — these two flavors together, creating something greater than they could ever be on their own. A new sensation that Emile has never experienced before.

That’s what it’s like eating at Bastia.

On a warm autumn night I’m sitting in chef Tyler Akin’s understated dining room just off the lobby of the boutique Hotel Anna & Bel in Fishtown. My daughter is with me, smart and beautiful and home from college on a short break, and we both say the same thing at the same time. We’re sharing a plate of Honeycrisp apples soaked in spiced honey, the plate dotted with folds of lonzu and cubes of seawater-washed Perrystead Atlantis, and she looks up and says, “It’s just like that scene in Ratatouille — ”

“When Ratatouille gives the grapes and cheese to his brother. It is.”

“The rat’s name is not Ratatouille. You know that.”

“I do know that.”

A spread of seasonal dishes

The plate is so simple. So perfect. It is emblematic of nothing about cooking and everything about being a chef — the choices made, the careful balancing of flavors, the knowledge of what must go with what to balance sweet against salt against savory against spice. Fireworks. Every time we take a bite.

AT A GLANCE

Bastia

1401 East Susquehanna Avenue, Fishtown

CUISINE: Corsican seafood

PRICES: $$$

Order This: Anything, really, but if the swordfish

is on the menu, go for that.

At our corner banquette, under soft lights, we ate shaved bluefin tuna with bottarga, sundried tomato, and little green rounds of sliced olive, and pasta cupped like seashells dressed in a wisp of lemon butter sauce and tossed with chunks of Maine lobster. There were grapes and burrata served with hazelnuts and dark chocolate, split langoustines marked on the grill, and skate cheeks over polenta with a brown butter crisp touched with the smoky sweetness and strange vegetable softness of Jimmy Nardello peppers, and all of it bled together like the dreams you have just before waking — hyper-real but blurred around the edges, sweet and wistful both at the same time.

I drank cold gin and told my girl she had to try the ricotta dumplings I didn’t even remember ordering because I was envious of her lobster. They were Corsican-style storzapretti — fork-soft but firm, threaded with chard, rich without being overwhelming — in a sharp arrabbiata punctuated with salty guanciale.

Storzapretti at Bastia

“It’s good?”

“So good,” I told her, pushing the bowl across the table. Then, when her hands were full, I stole some of her lobster.

Next was herbed pork belly with roasted new potatoes over Sardinian flatbread called pane carasau. It was perfectly trimmed and fanned, roasted with wild maquis herbs, the potatoes split and cooked hard so the insides steamed. It would’ve been the highlight of almost any other table in the city. Here it was just the thing we pushed aside before descending like starving wolves on the best swordfish I’ve had, possibly ever. Brochettes, on skewers, grill-charred but meltingly soft on the tongue. Served with black rice, with a walnut pesto that could’ve made shoe leather sing, with a smear of gently spiced labneh that added just the slightest touch of acid, there was nothing about the dish that wasn’t perfect. Like the egg raviolo they used to do at Res Ipsa after the sun set on Walnut Street, made to split and bleed yolk into a warm brown butter sauce, it was a dish I knew I could eat one bite of and remember for 20 years.

Scenes from Bastia’s dining room

“I’m sorry,” I said to my daughter, sitting across from me.

“For what?”

“Because you’re probably never going to have swordfish this good again in your life.”

And she looked at me strangely, tilted her head, scowled, and asked me, “Dad, why do you have to ruin everything?”

4 Stars — Come from anywhere in America

Rating Key

0 stars: stay away

★: come if there are no other options

★★: come if you’re in the neighborhood

★★★: come from anywhere in Philly

★★★★: come from anywhere in America

Published as “Basking in Bastia” in the December 2024/January 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Can John Fry Revive Temple?

John Fry at Temple University / Photograph by Colin Lenton

“I’m not a real estate person,” John Fry says 10 minutes into a winding tour of Drexel’s campus on an overcast afternoon in late September. You could be forgiven for thinking otherwise. Fry, piloting his dark Volvo wagon while impressively avoiding the swarms of jaywalking students around him, has been dropping addresses and square footage like a high schooler rattling off SAT vocabulary words.

Across from 30th Street Station he points out an imposing flat slab of concrete that used to be the home of the Bulletin newspaper; the building has undergone a complete makeover, its once-windowless facade replaced with glass, and is now home to the multibillion-dollar gene therapy pioneer Spark Therapeutics. Down the street, there’s 3025 JFK Boulevard — a two-tiered skyscraper containing life sciences lab space on the bottom half and luxury apartments on the top. There’s 3151 Market — a misshapen blue-glass cube with a Drexel University flag blowing out front that will be home to 470,000 square feet of life sciences lab and office space. Just beyond that, 3201 Cuthbert comes into view, a square mass of beams emanating from the ground, which will eventually become yet more lab space.

The point that not-a-real-estate-guy Fry is trying to make is this: “One thing I know is that these real estate people do not like to go first. They want to know that someone is taking the risk and has confidence. And once that starts happening, then other things happen.”

There is certainly no shortage of things happening. As president of Drexel University, Fry kicked off a building bonanza, partnering with private developer Brandywine Realty Trust on Schuylkill Yards, a $3.5 billion life sciences and residential development that’s transforming the area around 30th Street Station. (Drexel owns the land and issued decades-long ground leases to Brandywine, which is paying for the construction.) Fry’s real estate philosophy is bearing out in real time: The Bulletin Building, 3025 JFK Boulevard, and 3151 Market Street are all Brandywine developments; 3201 Cuthbert is a $450 million project separate from Schuylkill Yards involving Drexel and an entirely different developer.

Fry is admittedly not just a builder. In his 14 years at Drexel, he has raised more than $1.3 billion and helped lead the school to Carnegie R1 status, a distinction afforded to only 146 of the top research universities in the country. (The other two in Philly are Penn and Temple.) “We’re not going to out-Yale Yale,” Fry says, but he has established a few institutional priorities — like the school’s autism research institute, which Fry announced early in his presidency — that have enabled Drexel to, in his view, “punch way above its weight.”

Still, the building is the most obvious sign of Drexel’s growth. Fry likes to think of Schuylkill Yards as an “innovation neighborhood” that serves to connect the Drexel students and scientists working in labs with nearby Center City. “I have a long obsession with public environment, how institutions and neighborhoods should interact in a much easier, almost boundaryless type of way,” he says. The form this obsession takes is a constant analysis of geography: where to build, how to build, how to integrate a project into the existing urban fabric. One of the first Schuylkill Yards projects was Drexel Square, a compact green space across from 30th Street Station with crisscrossing footpaths that from above looks like a flattened basketball. This would have been the “perfect site for a major tower,” Fry says; instead, Drexel and Brandywine created what he likes to think of as Philadelphia’s sixth square.

As we zip around University City — past new residential towers dotting the eastern bank of the Schuylkill (more proof of Fry’s theory) — the tour begins to take on the feel of a victory lap, though Fry would hate the term. “We’re in the super-early innings here,” he says at one point; at least three more Brandywine towers are planned, and Fry eventually believes a cap will be built over the Amtrak rail yards running into the train station, allowing construction to extend even further. But Fry will not be here to witness any of that: His race at Drexel is over. In November, he crossed the river and headed north to become the 15th president of Temple University.

In this game, if you want to make an impact, you probably want to make a commitment of at least 10 years. So I thought, ‘I’ve got one more window.’” — John Fry

When the news of Fry’s move first leaked, in June, it qualified as a shock. With a little more consideration, though, it begins to feel like the most obvious next step in the world. Fry, who played a major role in transforming West Philly as executive vice president of Penn in the ’90s, who as president of Drexel since 2010 has turned a campus once rated the nation’s ugliest into a place where skyscrapers sprout from the ground like dandelions, who has used the might of universities to change neighborhoods, is taking on the challenge of Temple. Judith Rodin, the former Penn president who hired Fry in the ’90s, describes Temple and North Philly as “the last piece of Philadelphia that really needs the kind of integrated, intervention set of strategies” that she and Fry deployed in West Philly.

Fry feels drawn to Temple, which in recent years has been unmoored, struggling with a 25 percent drop in enrollment — down to 30,000 students from 40,000 just seven years ago — while confronting a public safety crisis spurred by the murders of a student and a university police officer in the past three years. The neighborhoods around the school are some of the most economically disadvantaged in the city; in the 19121 zip code just west of the university, the median household income is $35,700 and the poverty rate is 40 percent. Two of Temple’s last three presidential hires have not even made it through a five-year term. But for all of Temple’s challenges, it retains an irresistible appeal: It is the city’s sole public university, and ever since a minister named Russell Conwell began tutoring working Philadelphians in a church basement in 1884, Temple has maintained that access to an excellent education is a core part of its mission. The degree to which Temple lives up to that mission has arguably as much impact on the future economic and social health of Philadelphia as any institution in the city.

If the move seems obvious, though, Fry insists it wasn’t. When Temple approached him in early 2024 to see if he would be interested in the position, Fry did not experience the glorious revelation of new possibilities. Instead, he began to feel sick to his stomach. After 14 years, he was struggling to envision leaving Drexel, even if some part of him knew it was time. “In this game, if you want to make an impact, you probably want to make a commitment of at least 10 years,” Fry says. By that point, Fry, who’s 64, will be in his mid-70s. “That’s probably around the time you should hang up your spikes as well,” he says. “So I thought, ‘I’ve got one more window.’”

No one grows up dreaming of being a university president. It is the kind of job you usually ascend to by doing something completely different: being a professor. Fry took a less conventional path. He grew up in Brooklyn and made his way to Pennsylvania after being recruited to run cross-country at Lafayette College. He chose an interdisciplinary major called American Civilization. “That’s sort of when the city bug started to bite me,” he says. Budding urban interests aside, Fry was not thinking about a career in the academy. He wanted to go to law school.

After a disappointing showing on the LSAT, he had to make other arrangements. He ended up at the accounting firm Peat Marwick (a predecessor of KPMG), going through a boot camp that trained liberal arts grads in the illiberal art of public accounting. For the next two years he worked while taking night classes for an MBA. Eventually, he was assigned to a project at Virginia State University. Impressed by his work, his bosses asked him to transfer to the higher-ed consulting division of the firm; Fry was happy to oblige. “It was serendipitous, and definitely not that much of a plan,” he says.

Serendipitous moment number two: More than 10 years later, with Fry still working in higher-ed consulting, he was starting a new gig for the University of Pennsylvania. The school’s president, Sheldon Hackney, had left after more than a decade, and Fry had been brought in to review Penn’s administrative structure. One of his tasks was to help Rodin, the new Penn president, fill a vacancy for executive vice president, essentially the university’s chief operating officer. One weekend, Rodin called Fry to discuss the four finalists. “We ended the conversation and he said to me, ‘You know, I’ve gotten to know you very well, and you don’t sound enthusiastic about anyone,’” Rodin recalls. Rodin’s next move was straight out of a Nora Ephron rom-com: She told Fry, “‘I think you would be the perfect choice.’ And he just sort of gasped.”

Fry’s response was to tell Rodin she’d be crazy to hire someone with no real experience. “I really made a strong case because she was my client,” he says. “Of course I was flattered. But I just did not think I was the right choice. I think she probably said to herself, This guy will always have my back; if he’s willing to throw himself under the bus, he must really sort of care about me.” Fry lost the debate and got the job.

John Fry / Photograph by Colin Lenton

The Penn that Fry walked into in 1995 bears little resemblance to the institution of today, in large part thanks to what Fry and Rodin would soon get up to. “It was the perimeter that was really in trouble,” Fry recalls. There was little in the way of retail or foot traffic along the corridors of Walnut Street and 40th Street. “People just felt creeped out after dark,” he says.

The problem of campus safety came to a head in 1996 with the murder of a research associate named Vladimir Sled. Sled had been walking home with his fiancée near 43rd Street and Larchwood Avenue when someone tried to rob his fiancée. Sled intervened and was stabbed. “The Penn campus exploded,” Fry says. “It was like the last straw.” Though public safety had been a long-standing concern, in the aftermath of Sled’s murder, “all the excuses that Penn had given about why Penn can’t impact its environment kind of were no longer viable excuses.”

The various responses Rodin and Fry came up with would eventually come to be known as the West Philadelphia Initiatives. Penn brought together neighborhood businesses and institutions to create the University City District, a nonprofit business improvement district — largely funded by Penn at first — that provided foot patrols and cleaning services to the streets bordering the campus. Fry played an instrumental role in boosting the retail around campus, bringing a hotel to Walnut Street and a movie theater and grocery store to 40th and Market. (Penn spent $170 million on those two projects alone.) At the same time, Penn sought to entice faculty and staff to move to the neighborhood and fix up the housing stock, offering mortgages at 120 percent of a home’s value, plus a forgivable $15,000 loan for repairs. The university also created a housing fund, with investment from the likes of Fannie Mae, to buy up rental properties — all the way from 40th Street to 49th Street and from Market Street to Woodland Avenue — that the university deemed to be in “deplorable condition” or whose poor management “threatened the stability of the neighborhood,” as Rodin describes it in a book she wrote detailing Penn’s efforts. But perhaps the most important move was that Penn partnered with the School District of Philadelphia to build Penn Alexander, a K-8 public school that could serve all those hypothetical new university-affiliated residents moving into the neighborhood. (Penn to this day provides an annual per-student subsidy, ensuring that it remains better-resourced than the average public school.)

Taken together, the suite of policies was as transformational as intended. The University City District, which also offers job training to community residents, is a blueprint for countless other business improvement districts across the city and country. Penn students today can walk down 40th Street at night, listening to music and scrolling on their phones without a care in the world. For Fry, a development ethos was beginning to take shape. “What we tried to do is reinstill confidence in the neighborhood by making sure there were basic neighborhood assets,” he says. “Places to shop, and especially to buy fresh food at reasonable prices. A place to send your kids to school. Houses that could be a little more affordable because the university was giving you a boost.”

Working at Penn in the ’90s was a kind of crash course in how a university can impact its physical environment. Fry started to think he might like to be a university president someday. He began a PhD in higher-ed administration, calculating, not unreasonably, that a university probably wouldn’t want to hire someone without a doctorate as president. But it turned out Fry didn’t need to go back to night school to get the job he wanted. In 2002, Franklin & Marshall came calling.

No disrespect to the great people of Lancaster, but this is a story about John Fry in Philadelphia, so we are going to vault over Fry’s eight years at Franklin & Marshall, except to note two key details: It was at F&M that Fry began to establish his reputation as a builder of projects no one thought possible. When Fry arrived at F&M, there was a rail yard bisecting the campus. What did Fry do? He got the rail yard relocated. “It’s impossible to move a train track,” says Craig Carnaroli, Penn’s current executive vice president. “But he got it done.” The second relevant detail about Fry’s time at F&M is that he never really took his eye off of Philadelphia. In 2006, Fry was asked to interview for the presidency of none other than Temple University. Fry did the interview, but while driving back to Lancaster, he realized he hadn’t yet accomplished much of anything at F&M. “It would have been really premature to have left,” he says. When he got home, he called Temple to withdraw from the search.

If you assemble the educational assets and you marry up talented people with big opportunities, eventually you can make these things” — innovation and inclusion — “connect.” — John Fry

When Fry took over as Drexel president in 2010, it was a sort of homecoming: back to University City, back to a private research university, back to a campus that needed serious work. But Fry did not come to Drexel with the idea of building skyscrapers. What he knew was that he wanted Drexel to become the most civically engaged university in the country. “It felt to me like the extension of A.J. Drexel’s vision,” he says. “He didn’t find a nice suburban location to put this. He put this in the middle of what was the heart of industrial Philadelphia back in 1891. I mean, rail yards and slaughterhouses and God knows what else. So I thought, 120-plus years later, what’s the next gesture that an institution like this should take? And it just felt like the civic stuff was a missed opportunity.”

John Fry in 2010 after accepting the role of Drexel president / Photograph by Mark Stehle/Associated Press

Over time, skyscrapers and Fry’s “innovation neighborhood” are what emerged. At the center of it all, as at Penn, is a school. “This is the magic,” Fry says on our drive as we approach the sleek, low-slung gray structure that houses Powel Elementary and Science Leadership Academy Middle School. “We built this school from the ground up.” Fry, who calls this the “single hardest project I’ve ever worked on,” raised more than $45 million to construct the school; Drexel leases the building to the school district at the cost of $1 per year. Unlike Penn Alexander, which at its core was built as a neighborhood asset for potential new Penn-affiliated residents, Fry thinks Powel/SLAMS, as the new school is known, serves a different function. “We like to say that the young girl growing up in Mantua goes to the Powel Science Leadership Academy Middle School,” Fry says, “then goes on to Central High, then goes to Penn or Drexel, and then goes to work at Spark. But she started in 19104, and she had the educational opportunities.” Fry concedes that this is a “misty-eyed view of the world,” but he believes that “if you assemble the educational assets and you marry up talented people with big opportunities, eventually you can make these things” — innovation and inclusion — “connect.”

It is impossible to have a conversation about geography and urban universities without also talking about history. A few minutes after passing by Powel/SLAMS, Fry gestures at One uCity Square, another node of Fry’s innovation district. The building sits on land once occupied by University City High School, which was itself a product of a different kind of innovation district, as urban historian Laura Wolf-Powers notes in her recent book, University City: History, Race, and Community in the Era of the Innovation District. In the urban renewal era of the 1960s, the federal government, in concert with Penn and other universities, razed the Black Bottom neighborhood in West Philly, displacing hundreds of families to erect the University City Science Center, an original innovation district. University City High School was meant to educate the students who would eventually populate the innovation district — much as Fry envisions Powel/SLAMS. But University City High School — perhaps unsurprisingly, given the original sin of its creation — never lived up to its ideals and was instead marked by underfunding and student underachievement; by 2013, it was set for closure. Then Drexel entered the scene, teaming up with a developer to purchase the land for $25 million and build One uCity Square, its innovation do-over. (In further proof of the impossibility of outrunning history, Drexel’s new building is actually a partnership with the University City Science Center as well, though you wouldn’t necessarily know it because the Science Center has since rebranded itself as uCity Square.)

The question to ask of any urban university development project is simple: Who benefits? Wolf-Powers answers one way, writing that “the capacity of innovation districts to deliver benefits” to the Black communities where they’re often sited “remains constrained, because the developers of these new urban spaces are designing them — physically, economically, and institutionally — around the capital, credentials, and purchasing power of people who already possess high socioeconomic status.” Another way of considering the question is to ask who gets to stay around to reap the benefits. In University City, thanks largely to the West Philadelphia Initiatives Fry had a hand in crafting, property values more than doubled, jumping from an average of $78,500 in 1995 to $175,000 in 2003, according to a WHYY report. (These days, the average home in the neighborhood goes for just under $500,000.) That may have been a boon to the residents who owned their houses, but it wasn’t to the much larger majority: renters. When the Penn Alexander school opened in 2001, 57 percent of the student body was Black; today that figure is just 13 percent.

Fry says he never expected the degree of change in the neighborhood around Penn. “I think in retrospect maybe we should have seen some of that gentrification coming, and we didn’t see it,” he says. “I know at least in the rooms I was in — and I’m pretty sure I was in all the rooms — there was never a conversation. We didn’t think gentrification could ever be possible in this neighborhood.”

John Fry with a Powelton Village resident in West Philly / Photograph by Mark Peterson/Redux

Given that legacy, one might expect Fry’s reputation in West Philly to be checkered. In some corners it certainly is. In a 2022 article about a Drexel development project, the school’s newspaper quoted a student activist blaming Fry for “leading the destruction of West Philly communities since the ’90s.” (The student then went on to erroneously state that the University City District was responsible for demolishing homes in the neighborhood.) But at least according to many of those who have worked directly with Fry, he is far from an object of acrimony.

Sheila Ireland, who lived in West Philly in the ’90s and was the founding director of the University City District’s workforce development program, doesn’t blame Fry for the market pressures wrought by the West Philadelphia Initiatives. “It’s always a double-edged sword,” she says. “Do I have sympathy for folks that are experiencing displacement or rising taxes and assessments that they can’t keep up with? Absolutely. But by the same token, would I have changed any of the approaches? Probably not.” Della Clark, who runs the Enterprise Center, a nonprofit that provides capital to minority-owned businesses in West Philly, rejects the gentrification line of inquiry altogether. “Gentrification in most people’s lenses is a white person walking with their dog in a community that was previously dominated by diverse families and now has got white families,” she says. “I don’t believe in that. I think there should be blended families, blended people in one community.” In Clark’s view, Fry’s work has been in service of making that more of a reality.

Fry, to his credit, has modified the playbook during his most recent chapter at Drexel. By way of proving the point on our tour, he drives us north of Spring Garden Street into the neighborhood — in this case Mantua. Here we look at the physical manifestation of Drexel’s, and Fry’s, evolution: the Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships. The center was in no small part formed as a response to Drexel’s prior relationship with its neighbors, which Fry flatly describes as “terrible” and “one of real neglect.”

Fry’s answer was to build a community resource that is steered by members of the community; based on feedback from Mantua residents, the Dornsife Center offers everything from a free legal clinic to a primary care facility for uninsured patients to a community writing class. While there may always be an inherent tension between the expanding university and its neighbors, De’Wayne Drummond, the current president of the Mantua Civic Association, says he found in Fry a willing partner. “He did more than other people have done,” Drummond says. “At least he tried. John also realized our community motto — Plan or be planned for. You’re not just coming in here making decisions for us. We can make decisions for ourselves. And I think John understood.”

Schuylkill Yards will undoubtedly exert pressure on a neighborhood like Mantua, but it does seem to differ from Penn’s West Philadelphia Initiatives in one meaningful way: It is not so much a neighborhood improvement project as it is a neighborhood creation project. Fry has very consciously avoided building outside the campus core. “We have literally never crossed Powelton Avenue, other than the Dornsife stuff, which was an abandoned piece of property that everyone considered an eyesore,” he says. In fact, Drexel has built more than 3,300 new student housing units during Fry’s time as president — part of a long-term bid to suck transient, partying students back onto campus and away from neighborhoods like Mantua and Powelton Village. A coalition of neighborhood groups has also managed to extract some concessions from Brandywine. As part of a community benefits agreement, the developer agreed to give $9.3 million over 15 years to the coalition for affordable housing support and other initiatives; the neighbors also succeeded in changing zoning regulations, making it harder for developers to build multi-unit student housing by right.

Across the street from Dornsife is the West Philadelphia Community Center, a rec center that was set to be demolished and sold to a residential developer building more student housing — “the last thing this neighborhood needs,” Fry says. Drexel outbid the developer, and after a $2 million renovation, the rec center is still a rec center. This type of community engagement represents Fry’s solution to the gentrification problem. “The reason why so many of these things are community-facing is precisely to combat that,” he says. “Because we’re doing this with our community, and our community is not going to give us advice that’s going to end up creating a situation where everyone is going to lose their house.”

Fry maintains a devotion to his work that fits the profile of tech CEO more than that of university president. He wakes up around five in the morning, then goes to the gym. At the office, he schedules upwards of a dozen meetings a day, stacked in rapid succession. At night, there’s usually some kind of a dinner. Fry lives in Chester County with his wife, Cara, an art historian who has worked as a volunteer at Drexel, curating shows on fashion history. Despite the peculiarities of his job, Fry has taken pains to establish a semblance of a normal life. “Weekends we really try to keep for ourselves and kids,” Fry says. Their three kids are now grown — Fry is a newly minted grandfather — and all three still live within driving distance. Still, work manages to creep in on the margins. Fry has been at work, haltingly, on a book for Princeton University Press about university development. Even a look at his bookshelf offers a reminder: He owns a 5,000-book collection of university histories and biographies of university presidents.

This style of work does not come without costs. On the eve of the pandemic, as Fry approached a decade at Drexel, he was close to accepting a job outside of academia entirely. Fry won’t go into more detail, except to say that the disruption of the pandemic made him recalculate and recommit to Drexel. Still, there seemed to be a faint recognition that Fry’s work habits might not be totally sustainable. When he told his wife about the Temple opportunity, she encouraged him, but also offered a caveat: “She said, ‘Look, do this if you want to do this, but try to do it in a different way relative to the kind of impact on us and our time. Go out and work hard, but don’t take it as personally as you’ve done in the past,’” Fry says. This is a little like telling Wile E. Coyote not to run off the cliff, but Fry has pledged to make a good-faith effort. “I don’t think she would have said that if she didn’t really mean it,” he says.

By 2021, Fry felt he had reestablished Drexel on firm footing and started thinking once more about his next move. That July he gave an interview with the Inquirer essentially pre-announcing his departure, telling the paper, “The art of this game is you don’t overstay your welcome. I’m starting my 12th year. I’ll finish that out and who knows beyond that, but not a whole lot more. It’s time for the natural cycle of change.”

That same year, Temple hired a president it hoped would be leading the institution for its next decade. Instead, Jason Wingard lasted less than two years. Wingard’s tenure was undone by a confluence of factors: a disengaged management style that alienated many of his subordinates, a grad student strike to which Wingard responded by cracking down and revoking students’ tuition benefits and health care, and a public safety crisis. In 2021, a student named Sam Collington was shot and killed in a broad-daylight carjacking one block from Temple’s campus; two years later, Temple police officer Christopher Fitzgerald was fatally shot while stopping a group of carjacking suspects on the street. After Wingard’s resignation in 2023, Temple tapped longtime professor and law school dean JoAnne Epps to serve as interim president. In September of that year, Epps, who had gamely agreed to postpone her retirement to help right the ship, collapsed on stage during a Temple event and died.

This was the environment Mitch Morgan, the chair of Temple’s board of trustees, had to contend with while beginning yet another presidential search. Morgan, a billionaire real estate investor and recently minted part owner of the Phillies, had previously drawn criticism during the Wingard search for not giving faculty enough input into the process. “I definitely went in this time saying that we want to get this right, and we don’t want to make this decision from the boardroom,” Morgan says. At a meeting with faculty, Morgan asked whether anybody had examples of a president they thought would be a good fit for Temple. Someone volunteered Fry’s name. Morgan wasn’t overly optimistic; despite Fry’s public comments about leaving Drexel, he appeared to have changed his mind and in 2022 signed a contract extension through 2028.

As word got around that Temple was interested in John Fry again, people close to Fry started pitching him, unprompted, on the position. Among the cavalry was Governor Josh Shapiro, who had gotten to know Fry while serving with him on the transition team for then-Governor Tom Wolf. “He reached out more as a friend and encouraged me to take a look at it,” Fry says. “It wasn’t a sell.” (It definitely was a sell.)

By the time Fry agreed to interview, the search committee had already narrowed the candidate pool to four finalists. He was the last to interview, and he prepared an hour and a half’s worth of comments on the university — where it could be doing better, where it was doing well already. “He knew everything,” Morgan says. “He read the bylaws.” When Fry left the room, Morgan stayed silent, waiting for the committee to render a verdict. “They unanimously said he is amazing, he has everything we’re looking for, we have to figure out how we can get him,” Morgan says. A few days later, Fry had a job offer.

That still left the matter of Drexel. Fry had spoken into existence the prospect of his leaving, yet he still found himself hesitant as he approached the precipice. “It’s not an easy thing,” he says. “And I have a lot of Catholic guilt to begin with, so you can just imagine.” But the voices in his ear encouraging him to take a chance won out.

What happened next did not go as planned: Fry had intended to announce his move at Drexel’s board meeting in September 2024, with the idea of staying the entire academic year, until a successor was named. Instead, in June, someone leaked the news that Fry had accepted the Temple job, and Fry found himself calling members of the stunned Drexel board. “It’s really unfortunate,” he says. The leak ended up hastening Fry’s exit. Drexel tapped a longtime trustee to serve as interim president; Fry’s last day would be September 30th.

In classic Fry fashion, he spent the last day of his employment at Drexel calling donors, squeezing out every last hour.

At 8:30 the next morning, the first day of his unemployment, Fry, in his usual black suit, stands in front of Sullivan Hall, the gothic building housing Temple’s administrative offices. Until now, Fry hasn’t spent much time on Temple’s campus, for fear of giving the impression that Drexel didn’t have his full attention. Newly unburdened — and happy to share that he did his morning workout wearing a Temple t-shirt instead of his usual Drexel one — Fry is here to take a tour of the campus with chief operating officer Ken Kaiser.

Kaiser, a Temple grad in a gray suit who has the wheeling and dealing energy of a Miami real estate agent, spends the next hour detailing Temple’s considerable real estate plans, starting with the $167 million renovation of Paley Hall, the school’s brutalist-style former library, into the new home for the College of Public Health.

Although Temple is situated in the middle of dense North Philly, additional future development opportunities abound, as Kaiser cheerfully points out throughout the walk. He highlights no fewer than five different parking lots owned by the university that will eventually be developed. Kaiser mentions plans to demolish a group of buildings across from the new Paley building to make way for a central quad befitting a great university. The site that for years was slated for a controversial football stadium is instead going to become a performing arts center and the home of the Klein College of Media and Communication. Temple has been gobbling up additional parcels along North Broad as well.

Part of John Fry’s charge at Temple will be to grow enrollment and allay long-standing concerns over public safety on campus. / Photograph by Ryan S. Brandenberg for Temple University

One thing that quickly becomes apparent is how much further along Temple is in its campus and neighborhood development than Penn and Drexel were when Fry got there. At Penn, Fry had to bring a movie theater and grocery store to the neighborhood; Temple’s already got both, right on Broad. As for the campus, it may not have quite the architectural grandeur of Penn, but it’s in no danger of being named to any ugliest-in-the-country list either. The place feels truly vibrant, thanks in large part to who’s walking around. There is every kind of student imaginable: kids in do-rags, kids in hijabs, frat-bro types in sports jerseys, nerdy kids, stylish kids with shockingly baggy pants. Next to the Cecil B. Moore Broad Street Line station, there’s a small sunken plaza where every day you can find a crew of skateboarders kickflipping back and forth — a scene that would be unfathomable somewhere like Penn.

For Fry, the strength of the campus core means he can spend more time thinking about “the edges, which is where campus meets community. And if you’re going to develop more commercial, biosciences, tech uses, they’re going to want to be on the commercial corridors.” Fry says he’s “not so presumptuous to say I have any sort of a vision for Temple at this point,” although he has a few rudimentary thoughts, one of which is to better connect Temple’s main campus to its hospital campus, which is located a mile and a half up Broad Street. At the same time, Fry and Temple are keeping their eyes trained southward as well — to what was the UArts campus. Though merger discussions failed — reportedly after the main UArts benefactor, the Hamilton family, refused to allow the school’s $62 million endowment to be transferred in a deal — Fry is not giving up. “Should have happened,” he says of the merger. “It could have been a different story, and it didn’t work out, but that doesn’t mean that Temple still can’t find its place down there. To be determined.”

Despite these reasons for optimism, Temple is not without major challenges, chief among them public safety. The murders of Sam Collington and Christopher Fitzgerald have produced a major image problem for Temple. Fry recently met with the school’s athletic director, who informed him that families of recruits are frequently shocked, upon visiting the school, to find that the campus is actually nice. The challenge for Temple is that you don’t have to go far for the feeling to change. According to a report commissioned by the university after the two murders, from January to mid-August of 2022, there were 19 people shot within four-tenths of a mile of the main campus. In surveys, professors reported that students have considered dropping out because they don’t feel safe coming to campus for night classes. Some parents, the report found, have even gone so far as to hire private security for their children living off campus. The lack of on-campus housing also fuels the safety issue: Just 19 percent of Temple students live on campus, and the last dorm was built a decade ago.

A lot of people have a lot to say, and they want to say it to me directly. And I’m totally good with that.” — John Fry

The obvious solution to the public safety problem, for Fry, is a repeat of what worked at Penn: using a University City District-esque institution to bolster lighting, foot patrols, and cleanliness. Unfortunately for him, some of these institutions already exist, and they’re not exactly thrilled with Temple. Sheila Ireland, the former University City District workforce development leader, now works as the CEO of OIC Philadelphia, a North Philly workforce development program that’s been around since 1964. In the two years she’s been working at OIC, Temple hasn’t once invited Ireland to the university to talk. “They don’t appear to have an overarching strategy for how they’re engaging the community,” she says.

Shalimar Thomas, the executive director of the North Broad Renaissance business improvement district, is similarly disillusioned. In 2019, Temple announced that it was funding a brand-new special services district to the tune of $500,000. When Temple’s initiative was announced, Thomas says, North Broad Renaissance was listed on the website as a partner. “I’ve never met these people a day in my life. Never. And I’m listed as a partner?” The episode did little to quash the feeling that Temple had marginal interest in earnestly working with community members, although both Ireland and Thomas are optimistic that Fry’s arrival could herald a shift.

Fry, too, seems to understand that many people both inside and outside the institution have their complaints. “A lot of people have a lot to say, and they want to say it to me directly,” he says. “And I’m totally good with that.”

The past 25 years, according to Carnaroli, the Penn executive vice president, have been the “golden age” of higher ed: increasing enrollment, a booming stock market, endless philanthropy. That period happens to cover almost all of Fry’s time as a university president. The post-pandemic higher-ed environment Fry is working in today is one of flagging enrollment and budget cuts. Not long after Fry’s move to Temple was announced, Drexel shared unsettling news of its own: The school had a $63 million operating deficit in 2024 and a 15 percent decline in first-year student enrollment. At the same time, Fry will be coming to a Temple campus that has seen its fair share of student protests over Israel’s war in Gaza — protests that, at other institutions, felled a number of presidents. (In October, just before Fry’s start at Temple, the university suspended a group called Students for Justice in Palestine after a protest at a campus job fair.)

Nevertheless, it’s fair to say Fry will be starting with the wind at his back at Temple. Bucking the national trend, Temple’s first-year enrollment is up nearly 30 percent, and almost 500 kids have taken advantage of a new program that provides free tuition to low-income students from Philadelphia. For the third straight year, students of color make up more than half of the freshman class. Meanwhile, the faculty union just agreed to a new four-year contract, which should take some pressure off of Fry, who’s never presided over a unionized faculty before. For the most part, the mood at Temple seems to be one of jubilance. “Electricity is now in the air at Temple,” says Valerie Harrison, an administrator who served on the search committee.

What will success look like for Fry at Temple? Fry says he’s “not the kind of person who’s interested in coming in with a blueprint on the first day” and that much is dependent on what he hears from faculty and staff at the university. But with that disclaimer out of the way, he launches into a detailed disquisition: He believes the school needs to become more affordable. Enrollment needs to grow to around 35,000, which may require recruiting students from parts of the country (or world, even) that are far afield from Philadelphia. He anticipates a major fundraising campaign tied to the school’s 150th anniversary in 2034. Academically, he wants Temple to be thought of as one of the “great urban public research universities in the country,” which will require targeted investments in areas where the school can excel. “Only the very wealthiest institutions can afford excellence across the board,” Fry says.

And then there is the development side, where the goal is so obvious it scarcely needs to be said: “a real emphasis on strengthening the North Broad corridor from an innovation, a commercial, a residential, and retail standpoint.” And while Temple is just one institution, Fry is willing to say that he and the university should be judged on whether they can successfully impact some of the city’s most intractable problems of violence and poverty. “I think Temple very much owns those outcomes, along with city government, along with the other anchors,” Fry says. “That’s what people should expect of a great public institution.”

One thing Fry does not believe is that there ever was a golden age of higher ed. Which is maybe why the present moment doesn’t feel particularly daunting. “I know Temple can be full of its complexities, but I feel like I’ve been training for this all my life,” he says. “I’ve been doing this job since I’ve been 41. Every year is hard.” He goes on, “I am not overconfident about anything. I’m too experienced to be overconfident about anything, because things can come from all sorts of different places to surprise you. And I guess I feel right now nervous about this, not taking anything for granted, and feeling extremely humble and excited to get going. But you know, it’s nice to be my age and still be living on the edge of your seat.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story included an incorrect figure for the amount of money Fry raised during his tenure at Drexel.

Published as “John Fry’s Last Dance” in the December 2024/January 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Governor Shapiro Throws SEPTA a $153 Million Life Preserver

SEPTA’s buses, trolleys and subways will run as usual for the rest of the year thanks to an infusion of $156 million ordered by Gov. Josh Shapiro. / Broad Street Line photograph by Ben Schumin via Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

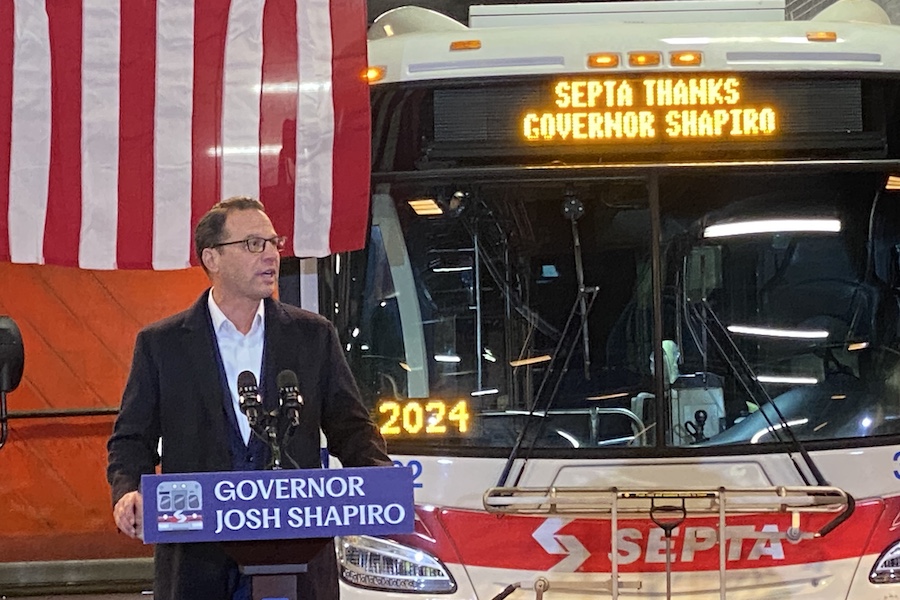

Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro announced this morning that he will provide $153 million in funding for SEPTA for the remainder of the fiscal year.

Standing in a bus garage at Frankford Transportation Center in Northeast Philadelphia, Shapiro ordered Pennsylvania Transportation Secretary Michael Carroll to transfer the money from seven highway projects across the state, most of which have yet to be started. The flexed funds will allow SEPTA to call off a planned 21 percent fare hike scheduled to take effect January 1st. The agency can also avoid deep service cuts this spring.

At the news conference, Shapiro touted this action as another example of how he works to “get shit done.”

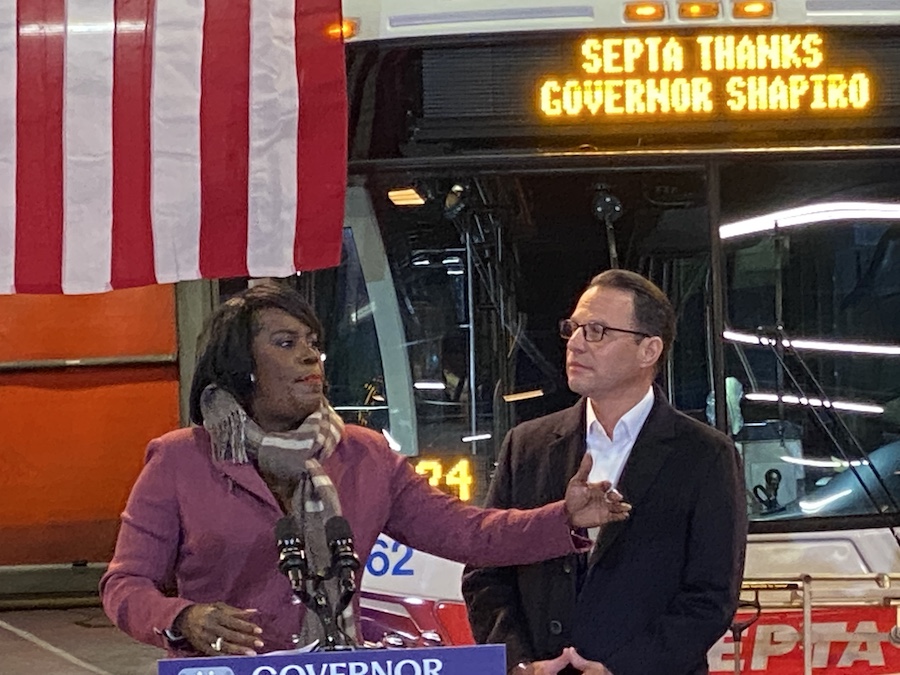

Along with funding from the Commonwealth, the five counties must also chip in money. Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker announced at the news conference that the city would add $30 million to its SEPTA contribution. Montgomery County Commissioners Chair Jamila Winder said her county would toss another $1 million SEPTA’s way. The other three counties in SEPTA’s service territory will also provide additional funding as the law requires.

Of course, all this merely buys time for SEPTA while Harrisburg figures out a permanent funding fix for public transportation statewide. Shapiro praised the state House leadership for passing his transportation funding package three times this year, but while “not pointing fingers,” he got digs in at the state Senate for repeatedly tacking on additional requests that he would agree to — then failing to pass a bill.

Gov. Josh Shapiro speaks at today’s news conference / Photographs by Sandy Smith

After praising SEPTA’s management, its unions, the police and construction trade unions, and the various elected officials who worked with him to make this happen, Shapiro devoted most of his remarks to the challenge ahead: Making sure that a new steady source of funding makes it into the fiscal 2026 budget.

Like many other big-city transit agencies, SEPTA relied on pandemic assistance funds and additional money supplied by the Inflation Reduction Act to continue to operate service at pre-pandemic levels after ridership crashed. While riders have slowly returned to the buses, trolleys and trains — ridership has recovered to 75 percent of pre-pandemic levels in the two most recent monthly reports — permanent changes in the way people work, especially remote work, mean that ridership will not return to pre-pandemic levels unless new sources of riders arise.

The end of the pandemic money left SEPTA some $240 million short on its fiscal 2025 budget. An infusion of $53 million in state money and local matching funds carried the agency through the fall; the fare hike and future service cuts announced November 12th would have both closed the rest of the gap and put SEPTA on what it called a “doomsday spiral.”

Mayor Cherelle Parker speaks as Governor Shapiro looks on

Several bills passed by the House this year would have averted this crisis, including one that allowed the five Southeastern Pennsylvania counties and Allegheny County to levy their own dedicated sales taxes for transit. None of them made it out of the Senate.

However, Parker offered reason to hope for a different outcome in the coming legislative session: she noted in her remarks that the last time PennDOT shifted highway money to SEPTA, former Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell served as governor — and the next year saw the passage of Act 44, the first successful measure to provide dedicated transit funding across the Commonwealth.

It might be worth noting here that both of the chief executives who did this hail from the Philadelphia region. Shapiro noted that the five Southeast counties are the state’s economic engine. While he suggested that this meant the region could figure out how to fund its transit system on its own, it also meant that most of the rest of the state needs tax revenue from the Southeast to fund its road and bridge repair projects — and he also touted the progress his administration has made on those fronts this morning. SEPTA is just one of 59 agencies providing transit service to communities large and small, all of which get some of their operating funds from the Commonwealth.

(left to right) State Rep. Greg Scott (D-Montgomery County), SEPTA Board Chair Ken Lawrence, Jr., and SEPTA boardmember William Leonard

In a news release issued after the conference, the Commonwealth Foundation, a conservative think tank, blasted Shapiro (falsely) for not cooperating with the Senate but also pointed out that SEPTA received an unusually high portion of its operating support from the state. “State funds account for 49.9 percent of SEPTA’s funding,” the release states. “This is disproportionately high compared to other large mass transit agencies.

“The state share for New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is 9.2 percent, for the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) 26.5 percent, for the New Jersey Transit Corporation (NJ Transit) 26 percent, and for Boston’s Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) 30.5 percent,” the release reads. The foundation, however, fails to note that at least three of those agencies — the New York MTA, NJ Transit and Boston’s MBTA — are units of their states’ governments rather than independent regional public authorities.

The release also noted that SEPTA gets a lower share of its revenue from fares than the New Y0rk MTA, CTA and MBTA do and that the county governments provide only 7.4 percent of its revenues. While a statewide funding fix is still needed, some of these figures also ought to rise. Shapiro said at the news conference that he has received commitments from the five counties to increase their share of funding for SEPTA.

In addition to Shapiro, Parker and Winder, a parade of elected officials, SEPTA brass and private business leaders spoke at the event, including both state House Speaker Joanna McClinton and Majority Leader Matthew Bradford, State Representative Jordan Harris, Independence Blue Cross CEO Greg Deavens and SEPTA Board Chair Kenneth Lawrence, Jr.

Updated Saturday, November 23rd, at 9:04 a.m. to correct the title of the first statewide transportation funding bill. Governor Rendell signed Act 44 into law in 2007; Act 89, which fixed flaws in Act 44, was signed into law by Governor Tom Corbett five years later. Mayor Parker referred to the latter bill in her remarks at Friday’s news conference.

The First Details About Jesse Ito’s New ’80s-Inspired Izakaya

Photography courtesy of dancerobot