Inside Par Funding: The Wild $550 Million Financial Scandal That Rocked Philly and the Main Line

Joseph LaForte and his associates claim they ran a legitimate lending business. The SEC and the Justice Department say it was a massive grift — and one of the biggest financial crimes in Philly history. What everyone can agree on? It’s gotten vicious.

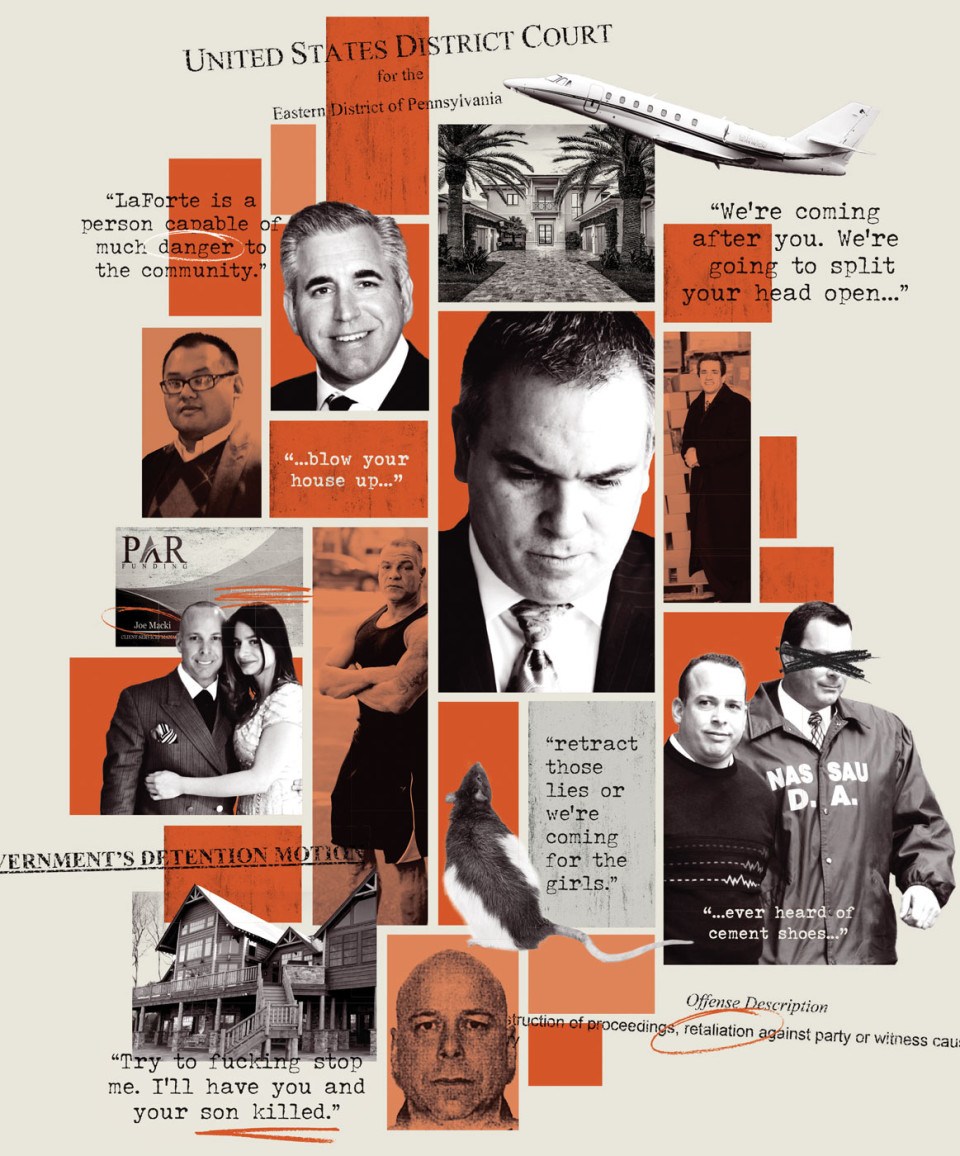

Inside the world of Par Funding: Perry Abbonizio; Stephen Odzer; Dean Vagnozzi; Joseph LaForte (being arrested); James LaForte; Joseph LaForte and wife, Lisa McElhone; Renato “Gino” Gioe; Joseph Cole Barleta / Photo-illustration by Leticia R. Albano; photography via Pelican Pix, LLC (Florida home), Aaron Lee Fineman/Hikari Pictures (Stephen Odzer), New York Post (arrest photo); Jefferson Siegel (Renato Gioe), Getty Images (plane and rat)

The lure was a free dinner and the promise of returns as high as 14 percent. The key pitch came from Joe LaForte, a two-time felon whose prior financial trickery cost his victims $14 million.

The 300 or so guests in the ballroom of the Sheraton Hotel in King of Prussia on November 21, 2019, didn’t know that. LaForte sold himself as someone with only their best interests in mind.

“Every day we go into the office, we understand there are real lives behind these investments,” LaForte told the gathering. “We really feel strongly about the fact that people are trusting us. You’re putting your trust in our company. And that’s meant a lot to me since day one.”

Moreover, LaForte said, he had put his own money on the line to launch his business, the Philadelphia lender known as Par Funding. “I started the company eight years ago with $500,000 of my own capital,” he said. “And here we are with $434 million in account receivables.”

And he went on: “Just to brag a little about the company, we’re probably the most profitable cash-advance company in the United States — or maybe the world, for that matter, pound for pound.”

Par Funding’s financial model wasn’t complicated. It took in money from investors, touting high returns, and lent that money out at punishing interest rates to smaller merchants who couldn’t get loans from banks. The firm, its executives boasted, delivered great results in a burgeoning trade known as the merchant cash-advance industry.

LaForte, compact and with a signature buzz cut, was just one of a battery of pitchmen wielding microphones that night to sell Par Funding to the assembled middle-class diners. Par executive Perry Abbonizio, with salt-and-pepper hair and a distinguished mien, talked up the firm’s “rigorous operational standards” and how it had the “best underwriting in the industry.” That was why, he said, fewer than one percent of Par Funding’s borrowers defaulted on their loans.

LaForte and Abbonizio were teed up by Montgomery County financial adviser Dean Vagnozzi, at the time a ubiquitous media presence thanks to his years of heavy advertising on KYW and Talk Radio 1210. His ads touted his “alternative investments” and complimentary meals at Ruth’s Chris Steak Houses. Vagnozzi, a bulky man with an imposing square head, explained at the dinner that his recommended financial products, like Par Funding, weren’t for sale on the stock market and thus avoided its ups and downs. He gushed about how merchants loved borrowing from Par Funding despite the high payback charges. Investors would love it, too, Vagnozzi promised: “Everyone gets between 10 and 14 percent. The more money you put in, the more you get.” And he added breathlessly: “This is merchant cash, and we are knocking it out of the park.”

Unbeknown to the hosts, one guest that evening was a ringer. He was Ed Horner, a private eye hired by a lawyer for a beleaguered Par Funding borrower. Horner took a seat right at the front and put what looked like a car key fob on his table. It was actually a spy camera, available on Amazon for $49.

The footage he shot that night figures prominently in a federal criminal indictment and a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit against Par Funding and its principals. The SEC says LaForte and others engaged in a farrago of lies, misstatements and omissions that night and in many other forums for years. The feds say Par Funding amounted to a $550 million fraud — one of the biggest such crimes in Philadelphia business history.

For starters, investigators say LaForte hadn’t put up half a million dollars. “Not only did LaForte not invest his own money to start Par Funding,” the SEC suit says, “but he has in fact never invested in Par Funding.” For another, Par Funding wasn’t among the world’s most profitable companies. Earlier in 2019, in fact, its outside accountant had stamped its financial report with an “adverse opinion,” finding it was hiding its losses. Nor, contrary to leadership claims, was Par choosy about its lending. At the time of the 2019 dinner, Par had filed more than 1,000 lawsuits in Pennsylvania alone that sought more than $145 million in missed payments from defaulted borrowers.

Abbonizio didn’t mention that he’d previously been fined for unethical behavior by regulators and barred for a time from the financial field. Neither Vagnozzi nor anyone else mentioned that both Vagnozzi and Par Funding had agreed over the previous year to pay nearly $1 million in penalties for violating state securities law.

No one mentioned LaForte’s criminal record.

Before the SEC stepped in in 2020, LaForte and his wife banked tens of millions of dollars in a scandal that the government says churned on for years — marked by the couple’s lavish spending on real estate, high-end cars, paintings, designer watches and other toys. FBI raids turned up an armory of guns and $2.5 million in cash stashed in their three luxury homes. The saga allegedly includes “kicking up” of Par Funding money to the Mafia, the planting of a dead rat on the mailbox of an opposing lawyer, and a brutal assault in Center City that left another legal adversary with seven staples in his skull.

While the SEC has effectively prevailed in its civil case, the criminal indictment is one of the Justice Department’s most aggressive moves against the controversial field of merchant cash advances. Par Funding lawyers contend that the government has recklessly crushed a legitimate business; federal prosecutors, like the SEC before them, depict Par Funding as a ruthless business that exploited both its investors and its borrowers. The firm lied to the former and gouged the latter, they say.

You could say the entire story has a cast out of Ocean’s Eleven — minus George Clooney, Julia Roberts, and even an inkling of charm. At the center of the action was LaForte, now 53, who founded Par Funding only a few months after he got out of prison in 2011 for grand larceny, money laundering and illegal gambling convictions. He’d hired a digital “reputation manager” to push his convictions down on Google and adopted several fake names that hid his past from investors. LaForte was glib and genial when courting the moneyed, but prosecutors say he was a menacing bully when he turned on debtors and other perceived enemies.

There is LaForte’s entrepreneurial spouse, Lisa McElhone, a petite South Philadelphian eight years his junior who runs a hip Old City nail salon and once claimed to be worth $795 million. That might be debatable, but there’s no dispute about her and Joe’s $6 million jet or their multimillion-dollar homes on the Main Line, in the Poconos, and along the waterfront in Jupiter, Florida. Their digs in Florida were just a short drive from the home of Donald Trump Jr. and Kimberly Guilfoyle.

There’s Joe’s younger brother, Jimmy LaForte, 47, a.k.a. Jimmy Schillaci, identified as being a soldier in the Gambino crime family in a racketeering indictment last year. There’s Par Funding’s chief financial officer, Joseph Cole Barleta. He kept Par Funding’s books and was a competitive eater who entered the 2013 Wing Bowl under the nickname Johnnie Excel. There’s Stephen Odzer, the businessman authorities say paid about $9 million in kickbacks to LaForte — after Odzer was pardoned by Donald Trump on the last day of his presidency, wiping out a conviction for bank fraud. We’d be remiss if we left out Renato “Gino” Gioe, the tattooed bodybuilder who has pleaded guilty to threatening people who owed Par Funding. He said he might “stick a fork” in the head of one, prosecutors said, and allegedly warned another he would cut off the debtor’s hands if he didn’t pay up.

With advice from two top Philadelphia law firms, Par Funding operated in a Wild West loan realm under growing attack from consumer advocates, combative attorneys general, and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

The SEC filed its sweeping lawsuit in 2020, triggering a mammoth legal fight that so far has generated nearly 2,000 court filings and at one point pitted two dozen defense lawyers against a lone government attorney, Amie Riggle Berlin. Then, in late 2021, after months of scorched-earth lawyering, LaForte and others suddenly folded ahead of trial. Without conceding wrongdoing, they agreed to repay investors close to $230 million. But in May of 2023, federal prosecutors raised the ante. They charged the LaForte brothers, McElhone and Barleta with 63 criminal counts, ranging from securities fraud and loan-sharking to extortion and tax evasion. The defendants are to go on trial in April. Abbonizio has already pleaded guilty to conspiring with LaForte and others to commit wire fraud and securities fraud and given up his two Jersey Shore houses, each worth about $3 million.

Vagnozzi settled with the SEC for $5 million without admitting wrongdoing. He wasn’t criminally charged.

Joe LaForte’s roots are on Staten Island. There, his wealthy grandfather was known — according to federal prosecutors, the FBI, and New York police officials — as “Joe the Cat,” a lieutenant for the Gambino crime family. In 1987, the grandfather garnered headlines when the mutilated body of an enemy of John Gotti, the newly installed boss of the Gambinos, was found in one of many Staten Island buildings he owned — a candy store. The victim had been shot five times in the face.

However, in December 2018, a law firm hired by Par Funding insisted the grandfather was no mobster in a letter threatening legal action over a critical news story:

Joseph LaForte’s grandfather died a peaceful death at age 99, with no significant criminal history, never convicted of organized crime activity and leaving behind a valuable real-estate portfolio that was the achievement of a lifetime of legitimate work and investment.

The letter had benign words for LaForte’s father, too: “Joseph’s father was a hair stylist in Hollywood, and worked on many movie and television productions. That is, Joseph LaForte’s family business was show business, not some sort of unlawful activity.”

In promotional materials, Par Funding’s Joe LaForte boasted of his stellar career in the financial industry, his MBA, and his time as a “switch-hitting catcher for the Seattle Mariners.” In fact, he dropped out of two colleges, and the school from which he claims to have earned an MBA in 1992 offered no such degree at the time. The Mariners say he was briefly signed to a non-draft contract but never played a game for the team in the minors or the majors.

In his 20s, according to industry records, LaForte worked at several New York financial houses between periods of unemployment. With only a high-school education, he had enough financial acumen to pass several rigorous stockbroker exams.

In 2000, when LaForte was in his late 20s, a Staten Island contractor sued him and several others, blaming them for a $92,000 loss in an allegedly fraudulent investment. The lawsuit quickly took a bizarre turn. The plaintiff, builder Joseph Zarrelli, also sent a letter to financial regulators laying out his alleged loss. In the letter, filed as part of the public record in the lawsuit, he said he had been warned not to raise complaints because the defendants had ties to the mob. “I certainly would like my money back and not have to worry that some organized crime person is going to kill me like they intimated,” Zarrelli wrote. Zarrelli also took his allegations to the New York City police, according to the court file.

Within weeks, however, the contractor signed a new statement completely retracting any complaints against LaForte. His references to “organized crime and my fear for my life were a lie and completely fabricated by me,” he wrote.

In recent interviews for this story, Zarrelli said he signed the second statement under threat. He said his lawyer, Dennis Peterson, told him, “You gotta sign this or I can’t guarantee your safety.” Zarrelli said he believed a threat had been conveyed to Peterson and that the retraction statement had been drafted by an organized-crime figure and given to the lawyer. Zarrelli said he knew few of the details of that.

“Dennis Peterson was an organized-crime attorney, and he knew all the players. I took him at his word,” he said, adding, “I really resented signing that letter.”

Peterson leapt to his death in 2003 from the 10th floor of his Staten Island apartment building. At the time, he was out on bail under federal indictment for loan-sharking. LaForte’s lead defense lawyer, Joseph Corozzo, did not respond to questions about the Zarrelli matter.

In 2005, at age 34, LaForte was charged with masterminding a multimillion-dollar financial scam on Long Island — a crime strikingly similar to the one he’s now alleged to have carried out in Philadelphia. It was the same year he married Lisa McElhone. It’s unclear where he met McElhone, who grew up near 12th and Oregon in South Philly, the daughter of a maintenance worker for the Philadelphia school district.

As is alleged with Par Funding, the Long Island scam was very much a family affair. Along with LaForte, authorities arrested his father, James; his mother, Tina; and his younger brother, Jimmy. The clan was accused of setting up a fake law firm to take settlement money from homebuyers and siphon it off into various fronts. The local district attorney called it one of the largest money-laundering schemes he’d ever seen. Prosecutors said the family spent their stolen money on real estate and a stable of cars, including Bentleys, Rolls-Royces and Mercedes-Benzes. In a classic Ponzi maneuver, the LaFortes used money from subsequent victims to cover earlier rip-offs until the scheme collapsed.

LaForte’s next arrest came in 2009, while he was serving time for the money laundering. He was charged in federal court with operating an illegal gambling operation before he was jailed.

LaForte pleaded guilty to both crimes and was given prison terms for each. When he got out in 2011 after serving four years, he and Lisa got down to business. Within months, prosecutors say, the couple started Par Funding. The same year, his wife, a graduate of St. Joseph’s University, incorporated her nail salon, Lacquer Lounge, opening it in South Philadelphia before moving the shop to Old City. (Lacquer has been a repeat winner in this magazine’s Best of Philly awards.)

In a 2019 deposition in a borrower’s lawsuit, LaForte bristled when the plaintiff’s lawyers brought up his criminal record. He praised Lisa while downplaying his role with Par.

“She does her own thing. She’s a lot smarter than me. Since you already exposed me, when I was in jail my wife had to fend for herself because she’s very intelligent, very smart, and she formatted this whole business. I’m lucky to be involved in a sales capacity so I could have a job. As a convicted felon, I’m lucky to have a position.” The next year, he was less self-deprecating in an email to Par Funding’s lawyer at the Fox Rothschild firm. The email was made public in the civil case. “I am a winner,” he wrote. “I like to win at all costs … always … that’s all that matters to me is winning … nothing else.”

Over nearly a decade, Par Funding took in more than $500 million from 1,200 investors and gave out millions in loans to nearly 8,000 small businesses, merchants, trucking firms, contractors, medical offices and many others. All the time, the SEC and prosecutors say, LaForte concealed his role, often hiding behind aliases and keeping his name out of SEC filings.

Vagnozzi knew about LaForte’s criminal record but appears not to have been bothered by it. He has said in court papers that his lawyer told him those past crimes weren’t significant enough to tell investors about. Besides, “Everybody deserves a second chance,” Vagnozzi said the lawyer told him. Vagnozzi raised more than $100 million for Par Funding.

In an interview after this article was first published, Vagnozzi says he had believed in good faith that Par Funding was operating honestly. He says that he, his father and his father-in-law, had all invested substantial amounts of their own money with the company.

Par Funding’s business strategy depended on a controversial aspect of the law — an area of legal bottom-fishing. To get loans, Par required borrowers to sign a “confession of judgment.” These documents barred the merchants in advance from contesting Par Funding when it said they were behind in payments — and gave Par power to immediately garnish their bank accounts. As the Pennsylvania Supreme Court once wrote, a confession of judgment is “perhaps the most powerful and drastic document known to civil law,” the “equivalent to a warrior of old entering a combat by discarding his shield and breaking his sword.” But the practice was legal, the court found, as long as borrowers’ “helplessness and impoverishment was voluntarily accepted.”

The FTC banned the use of confessions of judgment against consumer borrowers decades ago. Many states, including New York, have followed suit to forbid or limit their deployment against commercial borrowers, too. But their use against businesses remains legal in Pennsylvania.

Another key Par Funding tactic was semantical. The firm didn’t characterize the money it lent as loans, but rather as “cash advances” in which Par was buying a share of the borrower’s future sales. Presto — this meant that Par, like others in the field, could argue it was exempt from usury laws capping interest charges for loans. Thus, critics say, Par was able to charge astronomical interest rates — often more than 100 percent.

Par operated out of offices on North 3rd Street in Old City. There, judging from SEC snapshots, LaForte set up quite a man cave, with leather couches and armchairs, a stocked bar, a wine cabinet and cigar humidor, countless ashtrays, a $2,500 Pac-Man machine, and walls lined with baseball memorabilia. LaForte was prominently showcased in a framed magazine article that had the friendly prose and look of a purchased piece — another example of “reputation management.” Its main photo showed a grinning LaForte in a pugilist’s pose.

For borrowers who fell behind, the blows were real. Prosecutors alleged that its collection techniques, as described in one Inquirer article, sometimes amounted to “little more than a successful old-school mob loan-sharking operation dressed up in a business suit.”

Defense lawyers dispute all that, arguing that LaForte and his colleagues are the victims of lies by disgruntled borrowers. LaForte’s legal team includes Brian J. McMonagle, well known for his successful defenses of Bill Cosby and Meek Mill, and New York City attorney Joseph Corozzo. Federal prosecutors there have called Corozzo the in-house counsel for the Gambinos, saying his father was a consigliere of the family and his uncle a captain. However, in 2010, a federal judge rejected a government bid to disqualify him from a case on that basis. Lawyers for other defendants in the criminal case declined comment for this article, but Corozzo spoke up in defense of LaForte.

“I believe he will be exonerated at trial,” he said. “If not for the intervention of the SEC, the business would be continuing to this day as a very profitable business.” LaForte, his wife and other defendants have pleaded not guilty.

For borrowers who fell behind, LaForte is said to have laid it on thick. “Do you want to take this to the streets? We’ll take this to the streets,” U.S. prosecutors say LaForte warned the wife of one debtor. “I’m going to put a bomb in your car, and when you turn it on, it’s gonna blow, and you’re going to go with it.” He allegedly also told the woman she would end up at the bottom of the Hudson River, that she would go to pick up her children at school one day and find them missing, and, resorting to cliché, that he wondered whether she had heard of “cement shoes.”

In another incident, prosecutors say, LaForte told a victim he would take control of all his assets, saying, “Try to fucking stop me. I’ll have you and your son killed.” LaForte’s lawyers deny that he has threatened debtors. In one court document, they cite a complainant’s supposed $11 million debt and say, “She has $11 million reasons to lie.”

As an especially intimidating collector, Par Funding deployed Gino Gioe, a former convict who told Bloomberg News that he traveled the nation to confront 700 debtors for the firm. In one confrontation, Gioe allegedly took the Rolex off a big debtor after lingering at his Florida business for hours. That day, the owner sent LaForte a text: “please call off the hounds … and by that, I mean that animal you sent down here.” Gioe pleaded guilty to Par-related extortion in 2022.

Even the lawyers apparently weren’t out of bounds.

For years before the SEC took action, Philadelphian Shane Heskin battled with Par as an attorney for aggrieved debtors. (He dispatched the private eye to the Sheraton Hotel dinner.) The court-appointed receiver in the case once called him Par Funding’s “arch-nemesis.” In 2018, Heskin discovered a threat on his mailbox — the word “prey” cut from a magazine and stuck to the box. Separately, his legal colleague, Justin Proper, found a dead rat atop the mailbox outside his suburban home. The pair concluded they were in no ordinary commercial white-collar legal fight. After finding the rat, Proper said, “I personally tried to stay extra-vigilant, being aware of my surroundings. We took additional safety precautions to be assured my family was safe.”

In the summer of 2021, SEC attorney Amie Riggle Berlin headed from her condo to its garage. Her young child was with her. They found their Jeep Wrangler covered in what appeared to be blood.

None of these incidents led to arrests or were definitively tied to Par. But Heskin’s and Proper’s legal skirmishing with Par now figures in the pending criminal indictment. In it, the government says both LaForte and Barleta repeatedly lied in depositions with the two lawyers and prepped two other Par employees and “coached them to lie” as well. The two men were charged with two counts of perjury apiece. The indictment says an unnamed top lawyer with the Philadelphia firm of Fox Rothschild, Par Funding’s law firm, attended the prep session and depositions, although no charges were brought against the firm. Fox didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In the massive paper pile generated by the SEC suit, a debate emerged about the nature of Par Funding: Was it a Ponzi scheme, much like the LaFortes’ Long Island mortgage fraud, or a legitimate, albeit ruthless, business?

Expert-witness accountants for the feds and the firm wrote lengthy analyses … in total disagreement. After SEC trial counsel Berlin flatly termed the business a Ponzi scheme in court in April 2022, outraging Par’s legal team, she agreed not to use the term. Yet a month later, she said in a court filing that Par Funding was “a fraudulent scheme and also used investor money to pay purported investment returns” — the definition of a Ponzi scheme.

The one undeniable thing, though, was the money, which rolled in for years and which LaForte and McElhone spent with abandon. In 2016, the couple moved into a $2.4 million gated estate in Lower Merion. Less than a year later, they acquired a rustic lodge in the Poconos for $2.6 million. In 2019, they put down $5.8 million to buy the Florida estate of Brook Lenfest, son of the late Philly cable magnate and philanthropist Gerry Lenfest. Perhaps emulating LaForte’s grandfather, the couple also spent tens of millions more buying dozens of elegant apartment buildings and storefronts across Center City. They loaded up on trendy art — $2.1 million of it in just one month — expensive cars and watercraft. In January 2020, they bought their priciest vehicle, a $6.2 million 12-seat Cessna Citation Sovereign jet.

In the fight with the SEC, LaForte and McElhone have pleaded the Fifth, using it as a shield to rebuff demands for a financial accounting. But in an email obtained by the case’s receiver, McElhone sent her husband a statement at one point that put her wealth at $795 million. “This is impressive!!!!” she wrote.

Then the wheels came off.

In April 2020, Vagnozzi sent investors a disturbing email. “Par Funding appears to be insolvent,” he wrote. “It’s as simple as that.” He blamed the pandemic, saying it had hurt the ability of borrowers to pay off their loans, and urged his customers to take a cut in their payments while Par rebuilt itself.

In July 2020, the SEC swung its hammer, filing its mammoth civil suit against Par Funding, Joe LaForte and his wife, Abbonizio, Barleta, Vagnozzi and others. Almost immediately, federal judge Rodolfo Ruiz II, sitting in Florida, where Par Funding moved its nominal office in 2017 to cut taxes, granted the agency’s demand that LaForte and others be stripped of control of the firm and an outside receiver be appointed. The judge gave the job to a Florida lawyer, Ryan Stumphauzer. The receiver in turn quickly appointed Philadelphia lawyer Gaetan Alfano as his counsel.

That same month, Joe LaForte was captured on another surreptitious tape. He was in a convivial mood when he and Abbonizio chatted over dinner and many drinks with two guests they thought were wealthy businesspeople. Prosecutors would later describe them as “undercover FBI employees.” The conversation turned from luxury glamping and Caribbean vacations to guns and what fun they were.

LaForte: I’ve got rifles. … I’ve got AR-15s, what do you want bro, come on.

FBI employee: I’d love to shoot one of those. … Do you have like a lot of cool guns to shoot?

LaForte: We’ve got everything. AR-15s. We’ve got, uh, sawed off shotguns, rifles. We’ve got, I don’t know, what do you want?

Convicted felons are forbidden to have guns. Within days, the FBI simultaneously raided LaForte’s homes in Haverford, in Pike County in the Poconos, and in Jupiter. In the Haverford master bedroom, the FBI says, it found a pair of loaded Smith & Wesson handguns in a nightstand and a loaded rifle under the bed. Two more handguns and two shotguns turned up in the home office and basement.

After LaForte was arrested on charges — still pending — of illegal possession of firearms, he said the weapons were either gifts to his wife or guns she bought after a knifepoint robbery at her nail salon. (In the police report for the incident, she said the robber took her $25,000 earrings and a wedding ring worth $250,000.) In the raids, the FBI says, they also found something else — a staggering amount of cash. They scooped up more than $590,000 in Haverford, more than $595,000 in the Poconos, and more than $1.2 million in Florida.

Some possible light was thrown on all that cash when prosecutors later brought their criminal case. The government contends that Par Funding’s top borrower paid millions in “under-the-table cash kickbacks” to LaForte for years. That borrower, businessman Stephen Odzer, had a criminal history of his own: a 2004 federal conviction for defrauding three banks of $16 million. Odzer was given an 18-month sentence. In 2021, President Trump pardoned him on his last day in office.

For months after the SEC began the first court proceedings against them, LaForte, his wife, and a battery of lawyers fought with the SEC before suddenly agreeing to disgorge millions of dollars back to investors. Without admitting any liability, they settled just before the civil case was to go to trial.

While that was a key development in the lawsuit, the legal battles have continued. The federal criminal case brought in May 2023 is closing in on a trial — and the scandal has taken an even darker and uglier turn.

Though Dean Vagnozzi wasn’t criminally charged, he now says he’s a ruined man.

Back in the day, one of Vagnozzi’s many pieces of online self-promotion was a video that showed him tooling along in a canary yellow Porsche, top down, on his way to his King of Prussia office. You see what he calls his “rather large” $800,000 Main Line house and watch him and his wife enjoying glasses of red wine. You see him cheering on his daughter at a St. Joseph’s soccer game. The message: He was a wealthy man living the good life.

Today, he says he has been stripped of his credit cards, loan accounts, and state license to sell insurance and reduced to driving for FedEx at age 55. His cars? Repossessed. The $27,000 soccer benches he donated to St. Joe’s? His and his daughter’s names have been scrubbed from them. He’s too embarrassed now to serve as a lector at his church, reading Scripture. He says he’s been subjected to death threats. No longer at the wheel of a Porsche, he has filed a court briefing with a photo of him, unsmiling, in his FedEx uniform inside a company garage.

In an interview after this story was first published, Vagnozzi says that he had little choice but to settle with the SEC because the agency had frozen his bank accounts, leaving him unable to pay lawyers for a lengthy civil trial. No one has alleged that he mishandled or misappropriated investors’ money, he says, adding that he had not harbored doubts about Par Funding because investors had done so well, year after year. “They paid like clockwork,” he claims. Moreover, he says he paid his lawyers $1 million over the years to review Par and the attorneys had repeatedly assured him and investors that everything was legitimate.

In a bid to recoup his losses, Vagnozzi turned on a key ally for nearly two decades: lawyer John Pauciulo, a partner at the big Eckert Seamans firm who had vouched for Par Funding’s financial products and even appeared with him in presentations for investors. Vagnozzi’s lawsuit, filed by Philadelphia lawyer George Bochetto, is brutal. It calls Pauciulo’s legal advice “amateurish, lazy, incomplete, and dangerously inadequate.” Strikingly, the suit against Pauciulo appears to disavow other “alternate” investments that had been touted by Vagnozzi over the years. In blaming Pauciulo, Bochetto wrote that two previous products were deemed illegal by the SEC.

Pauciulo, 58, has lost his job with Eckert due to the scandal. He was fined $125,000 by the SEC and barred from appearing before the agency for five years. In a long list of allegations against him, the SEC said he should have known that Vagnozzi was violating government rules about mass solicitations of investors. For its part, Pauciulo’s old firm agreed to pay a whopping $45 million into an SEC fund to repay Par’s investors. Despite all that, Pauciulo and Eckert are fighting Vagnozzi’s lawsuit, arguing that he was a former licensed broker, was plenty savvy about finances, and ignored legal warnings. (Pauciulo declined to give an interview for this story.)

In a final bit of irony — or, more aptly, chutzpah — Vagnozzi last year asked Judge Ruiz to help him in his suit against Pauciulo. He sought to bring a legal action to double the possible money available for payout in the case. Quoting from Vagnozzi’s own pleading, Ruiz acknowledged that the financial fiasco had taken a ‘tremendous emotional toll” on Vagnozzi. Yet, the judge noted, unlike so many others involved in the mess, Vagnozzi had been sued by the SEC as an instigator of the whole scandal. The judge rejected Vagnozzi’s request.

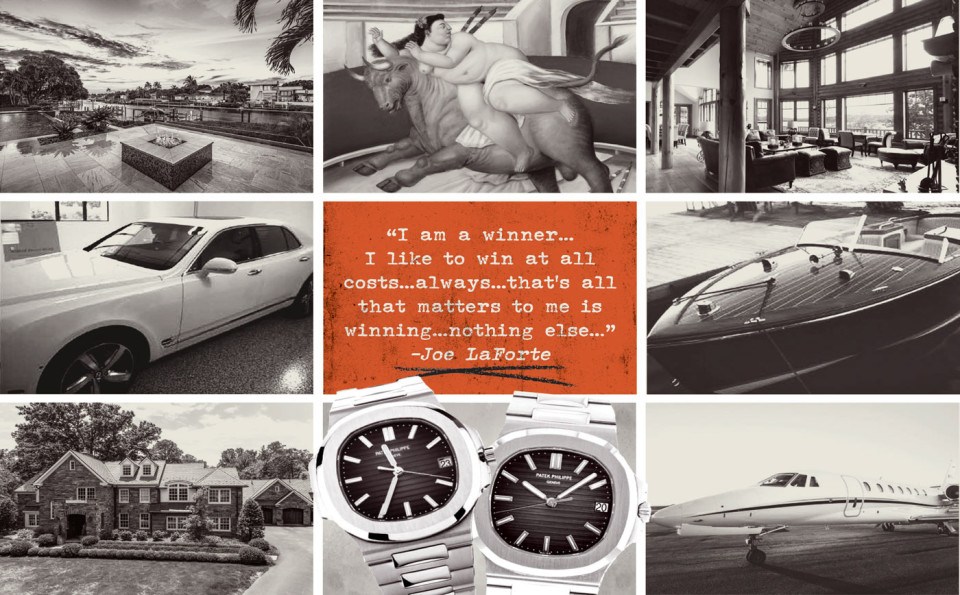

Some of the properties, artwork, vehicles and watches seized by the federal government from Par Funding founder Joseph LaForte and his wife / Photographs from court filings; photo-illustration by Leticia R. Albano

As the SEC pursued its lawsuit, receiver Stumphauzer began methodically clawing back the assets of LaForte, his wife and others. The campaign was led by attorney Alfano, a soft-spoken but relentless counsel to the receiver. The task wasn’t easy, given the stonewalling from LaForte and his wife. Nonetheless, Alfano’s team seized millions in cash and about $30 million in pricey real estate all over Center City, as well as LaForte’s and McElhone’s three houses. He took a Ferrari, their $232,000 Porsche, a $135,000 Bentley, a $100,000 Range Rover, and a $135,000 Mercedes SUV. He seized their $333,000 yacht, the $188,000 pontoon boat, and two WaveRunners. Alfano also took the couple’s art collection, highlighted by Fernando Botero’s Rape of Europa painting, purchased for $739,000. And he seized two Patek Philippe watches worth a total of $154,500. LaForte bought the watches just before the SEC went into court, the receiver alleged, faking paperwork to disguise the purchases as a Par loan to a borrower.

In the end, it appears that Par Funding’s 1,700 investors are about to be made largely whole, at least for their principal. The receiver hopes to return $250 million to them. One investor, Ron Grzywna, 62, while no longer staring down the barrel of a $600,000 loss, remains angry at LaForte and the rest.

“Had I known anything about him, I would have run away from the investment,” Grzywna said in an interview. “They fooled a lot of smart people. They got over on a lot of people very convincingly.”

For the borrowers, the outcome looks less positive. Though many of their debts have been written off, the receiver has rejected their claims for damages — even from those who were allegedly threatened. Moreover, the receiver is recommending that their lawsuits against Par be barred. Lawyers for the debtors aren’t especially sympathetic to the investors, some of whom collected high returns for years. “It’s interesting that the receiver is taking such a protective stand towards the investors,” Proper said. “They were making money taking advantage of small businesses.” In December and January, lawyers for merchant debtors, including businesswoman Kara DiPietro, went into court to challenge the receiver’s decision.

After Alfano’s team seized LaForte’s real estate portfolio, it hired Ori Feibush, the well-known Philadelphia real estate broker and developer, to put price tags on it all. Prosecutors say LaForte grew angry, thinking Feibush was low-balling the estimates, potentially increasing how much cash LaForte might have to disgorge due to a shortfall in real estate valuations. According to a government motion to keep LaForte in prison until trial, LaForte showed up at Feibush’s office in a “violent rage.” The government says he threatened to have the broker “clipped” and warned he had “500 men on the street” to do just that. In response, LaForte’s lawyers said that prosecutors had “grossly distorted” a mere disagreement.

Prosecutors say another victim of threats was DiPietro, who ran a Maryland firm outfitting commercial kitchens and cafeterias.

At first, her relationship with LaForte — or “Joe Mack,” as he called himself — was cordial. In one 2018 email, he urged her to enlist her father as an investor. He wrote: “I have 80 million in the company myself. So his money would be side by side w mine.”

DiPietro bought it. “I believed him because he was putting his money where his mouth was,” she said in an interview. But in 2019, when DiPietro fell behind in loan payments, LaForte’s tone grew different. “Get your fat ass up and call me,” he texted her. In a police report, she contended that LaForte even threatened during this period to blow up her house.

Last year, DiPietro was at home one night when her phone rang. By then, she was a government witness. “Kara, Kara,” a male voice said. “We’re coming after you. There’s a lot of us. You’re never going to know where we’re going to show up. We’re going to split your head open, you cunt.”

“I was really scared,” DiPietro, 47, says. “I think about it every single day, multiple times a day.”

The same week DiPietro got that call, attorney Alfano, 68, took a walk from his Center City office shortly after taking part in an afternoon Zoom court hearing dealing, in part, with the receiver’s demand that LaForte and his wife be evicted from their Main Line mansion. Suddenly, on 19th Street, someone raced up behind him and struck him in the head with a hard object. His scalp cut open, blood falling to the pavement, Alfano turned and glimpsed a man running away. A broken flashlight was left behind.

Alfano was treated at a hospital for his wound. In the days that followed, FBI agents methodically gathered up a series of surveillance videos. In a motion for pretrial detention, the agency says that while they don’t show the blow itself, they do show a man dashing up behind Alfano and then fleeing: Jimmy LaForte, the younger brother of Joe.

Prosecutors obtained a store video showing Joe and Jimmy together earlier that day in Center City. They say electronic records show that Joseph LaForte, under house arrest, had watched the Zoom hearing from his Haverford estate and when it ended called his brother on his cell phone. They spoke for a minute. When the FBI arrested Jimmy a few days later, agents found a crumpled note in his jacket pocket with the scrawled name Kara and DiPietro’s phone number.

Jimmy LaForte has a longer criminal record than his brother, with convictions for loan-sharking, arson and gambling along with the family mortgage scam. Apart from the charges he and his brother face together, Jimmy was charged separately last year in a federal criminal case in New York. Prosecutors there said Jimmy had become a “made” member of the Gambino family in 2019 and had “kicked up” more than $1.5 million in Par Funding money to a captain of the family. Jimmy LaForte has pleaded not guilty to all counts.

Both LaForte brothers are now in prison, awaiting the criminal trial in Philadelphia. Joseph LaForte was released after his initial arrest when his wife’s parents, along with four others, put up their home as security. He was jailed again after Alfano was attacked.

Lisa McElhone has yet to face hard times. She’s living in a penthouse apartment on the Parkway that goes for $9,000 a month in rent, according to the SEC.

And as the federal case heads to trial, prosecutors aren’t mincing words.

“They weren’t one-off crimes of passion. They were not chance encounters gone wrong. They were premeditated, they were calculated, and they were retaliatory,” prosecutors said. “[T]hey are further evidence that Mr. LaForte’s entire way of doing business, his entire MO, is to use violence and threats of violence to get his way. Your Honor, respectfully, these are the tools in LaForte’s toolbox.”

Now, they added, LaForte is facing “astronomical” time.

Published as “Loan Wolves” in the March 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

–

Update: On February 27, 2024, after this story was published, the Department of Justice charged Joe LaForte, Jimmy LaForte, and Joseph Cole Barleta with violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. Joe LaForte and his wife, Lisa McElhone, were also charged with tax evasion. The racketeering trial has been moved to October, and the tax case is scheduled for December.