This Life-Threatening Condition Is Underdiagnosed. A Local Physician’s Innovation Helps Kids Thrive

In 2017, Katelyn Sewell found herself at the center of a medical mystery. She was surfing with her dad in her hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina, a typical afternoon for the 15-year-old, when she felt suddenly and completely out of energy.

“I started to paddle out and I just couldn’t make it,” says Sewell. “My body would just physically not let me.”

That day, Sewell went from the urgent care to an ambulance to the emergency room, getting test after test. But at the end of the day, doctors simply told her she was anemic, had low hemoglobin, and needed blood. After a transfusion, she went home.

But in February of that same year, she was surfing in Hawaii with her friends and noticed the unmistakable lethargy return. “I didn’t even have the desire to surf,” she says. For her, that’s a big deal—a competitive surfer, Sewell had traveled to the likes of Barbados, California and North Carolina to test drive her growing talent, one she’d been cultivating since she was eight years old.

Sewell and her family began a long journey to find a treatment, one they wouldn’t find until years later, with an innovative, new intervention at Nemours Children’s Hospital. It’s there that children like Sewell come from across the globe to get answers about a mysterious, underdiagnosed, and life-threatening condition called Protein-Losing Enteropathy–and receive unique, transformative interventions that restore their health.

“There are hundreds of patients out there who probably don’t know that there are centers doing this [intervention],” says Dr. Deborah Rabinowitz, MD, chief of interventional radiology at Nemours Children’s Hospital in Delaware.

Today, Sewell is still surfing—and no longer just test driving her talent, but competing (and, often, winning) on a successful college team in Florida. Here’s how Rabinowitz and her Lymphatics Disease Program at Nemours Children’s are working to keep Sewell and young people all around the world living a healthy and active life.

The Disease

For Sewell, the time up to the diagnosis was long and frustrating, from the first moments of her struggle to the hospital stays, endless blood transfusions, and theories about her condition.

“I didn’t really know what was going on,” she says. “I just knew I was swollen and I had absolutely no idea why.” Sewell had an especially long journey to diagnosis largely because—besides the team at Nemours Children’s—there aren’t many health professionals who know exactly how to identify PLE.

Dr. Eric Sandler, a pediatric hematologist oncologist at Nemours Children’s Hospital, Florida, recognized Sewell’s low albumin as a marker of a lymphatics disorder. Albumin is a protein that comes from the liver. In Sewell’s case, the albumin was leaking into her gut instead of being sent into circulation.

She underwent colonoscopies and endoscopies, MRIs, angiograms, took octreotide shots for swelling, and a medicine called sirolimus which has been thought (but not proven) to help with lymphatic malformations in children.

Due to the medical uncertainty, Sewell was in and out of the hospital throughout her entire four years of high school, agonizing over decisions to take or not take medicine with brutal side effects, wondering if she’d ever get over this mystery condition. “It’s just always, constantly, on your mind,” she says. At one point, she even developed thrombosis, a type of clot, in her brain that sent her to the emergency room.

But once Sewell came to Nemours Children’s, and Rabinowitz and team were able to explore her diagnosis and condition, they came up with a real solution to the leaking albumin—one that had never been tried before.

The Search

Fortunately for Katelyn, the Lymphatics Disease Program at Nemours Children’s Hospital was primed to find a solution to her disease. Founded by Rabinowitz and lymphatics trailblazer Dr. Max Itkin, the program was her best shot. Before they developed a revolutionary treatment for Protein-Losing Encephalopathy, people who were diagnosed with the disease were just getting albumin transfusions to treat their symptoms. Rabinowitz and Itkin wanted—and successfully–developed a more precise treatment for their patients.

“Going to the hospital once or twice a week to get albumin transfusions while you’re not feeling well is just not a lifestyle for a 17- or 18-year-old girl,” Rabinowitz says, referring to Sewell’s case. “You have to try something, right?”

Still, the treatment, and even the PLE itself, is underrecognized. It wasn’t surprising that Sewell’s family had such a hard time finding a doctor who could diagnose her—although Rabinowitz specializes in and knows the lymphatic system well, it’s largely skimmed over during medical school.

“We spend maybe a morning on the lymphatic system in medical school,” she says. That meant that whenever they were talking to Sewell’s parents or even calling upon collaboration from other medical professionals, there was lots of explaining to do.

On Sewell’s end, Rabinowitz’s explanation went a long way. She felt like she made a personal and medical breakthrough when she arrived at Nemours Children’s.

“This was the first time that I felt like I was talking to doctors who knew more about my disease than I did from my own experience,” she says. She was refreshed by their experience working with similar conditions, and hopeful that they could make a real difference. “They knew all the right things.”

Rabinowitz and her team knew that they needed to find the exact source of the albumin leakage into Sewell’s gut and stop it. Even with Rabinowitz’ specialized experience, however, she would need to develop a novel intervention to fix Sewell’s particular condition. As a starting point, she looked to a treatment she developed and used for patients with heart disease. “What we figured out is that the patients who have heart disease have lymphatic fluid that leaks into their bowel from their liver,” she says. “So that was sort of the groundwork.”

Rabinowitz decided to perform a new, related procedure to investigate the liver and mesenteric lymph nodes to find where Sewell’s albumin leaks were coming from and stop the leaks. Sewell and her family were trusting and confident, even eager to invest in the plan. “I was ready to go there as soon as I possibly could, because it was the best news that I’ve ever gotten in my entire life,” she says. “I finally felt completely understood.”

A First-Of-Its-Kind Treatment

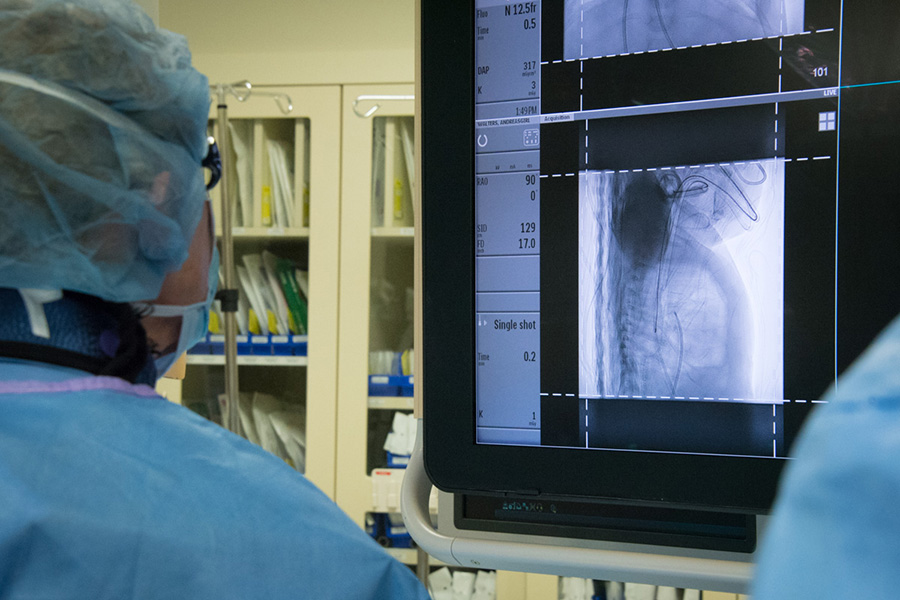

To find and embolize Sewell’s albumin leaks, Rabinowitz and her team at Nemours Children’s employed their life-changing intervention. Rabinowitz uses ultrasound and fluoroscopy to find the lymphatics in the liver and mesentery, and injects those lymphatics with a blue dye. Then a scope or camera is placed in the bowel and confirms leakage if the blue dye is in the bowel.

They found that they could reach those lymph nodes with a needle, identify areas that were suspicious, confirm said suspicion when the blue dye leaked through on-camera, and embolize that confirmed leak. “You can actually take a needle through the scope and very precisely put it in the exact hole where the leak is happening,” she explains. “So that’s what we did with [Katelyn].”

Rabinowitz and Itkin are the first to employ the method of putting the needle through the scope and directly into the leak. “The way we treat this is with something called medical superglue,” she says. “We find the leak, and we try to glue it shut.” They’ve taken this method around the country, presenting on the procedure so that other medical teams, like the one at Nemours Children’s, can change patients’ lives like they did for Sewell.

Rabinowitz’ procedure is a game-changer for patients and medical professionals everywhere. She’s had patients come to Nemours Children’s from around the world, hailing from Germany, Italy, Russia, California, Oregon, and more. Not only is she employing the procedure in her own operating rooms, but she’s also spreading the knowledge at conferences and talks so that more patients can have access to the treatment they need.

“The LGDA [Lymphangiomatosis & Gorham’s Disease Alliance] and the LMI [Lymphatic Malformation Institute] put together a conference where I’ll be speaking to families and physicians,” she says. Conferences like these are helping to normalize and bring awareness to this life-saving intervention. “We’re honored to be part of it.”

Going forward, Sewell may need treatment every few years to maintain her condition, but it’s worth it because life returns to normal—an outcome she long feared would never come. “I went to college, and I surfed as much as I wanted to,” she says of her life after the procedure. “I was able to travel, I could fly on an airplane, I could go on walks. I finally was a normal person, and it was so amazing.”

This is a paid partnership between Nemours Children's Health and Philadelphia Magazine