How the Always-Smiling, Always-Practicing Tyrese Maxey Became the “Absolute Key” for the Sixers

Three years ago, Maxey was playing high-school basketball. Now, on the eve of his third NBA season, Philly fans have embraced him with unprecedented verve, and Daryl Morey has called him the "absolute key" to the Sixers' title chances. No pressure, kid.

Tyrese Maxey is so practice-obsessed that head coach Doc Rivers has had to close the gym for the entire team—what he’s come to think of as the “Tyrese Maxey clause”—just to keep him out. Photo-illustration by Chris Crisman

Tyrese Maxey has just thrown a basketball at Spencer Rivers.

It’s a playful throw, but a throw all the same, and the ball caroms off Rivers’s back, hitting the ground with a thud. Rivers, one of the 76ers’ skills development coaches (and son of head coach Doc), has been guarding Maxey for the better part of an hour at the team’s practice facility in Camden, running through a sequence of rapid-fire offensive moves: every variety of layup in the known universe, quick-trigger mid-range jumpers, pull-up threes, balletic step-back threes. Rivers holds a padded pole — an attempt to re-create the impossibly wingspanned giants Maxey normally spends his time playing against — and tries to block shots. They’ve been keeping score: each make a point for Maxey, each miss a point for Rivers and the three other assistants running the drill.

For the moment, the skill Rivers appears to be most focused on developing is Maxey’s ability to tune out incessant shit-talk. Each time Maxey misses a shot, Rivers, like a mosquito buzzing in the dead of night, begins to taunt: “That’s on you! That’s on you!” Another miss. Rivers, gloating: “JAMES GUARD-EN. I’M JAMES GUARD-EN.” Now Maxey makes a shot. Rivers, screaming: “FUCK!” Another make. Rivers, still screaming: “FUUUUCK!”

It goes on like this until finally Maxey drains a three from the left corner. Workout concluded, it seems like détente might ensue. Then Rivers mutters, “You cheated.”

Maxey recoils as if he’s been physically struck. “What the — ” And now comes the throw at Rivers’s back.

“This elbow almost hit me,” Rivers says as they re-enact the play in question, in which Maxey may or may not have jumped sideways while shooting, fouling Rivers. Comically low stakes aside, they proceed, half-joking but also half-serious, neither wanting to be the one to concede.

“I. Missed. You.”

“You hit groin!”

Rivers calls out to a Sixers employee in a side room: “Pull up the tape!” And off they go to watch the instant replay, at 7:15 a.m. on a Wednesday in August.

For Maxey, who has made a habit of beating people to the gym ever since he was a high-schooler in the Dallas suburb of Garland, there was little exceptional about this scene during the dog days of the NBA off-season. He’s fond of saying that he prepares “in front of nobody to perform in front of thousands and millions,” and it’s the 6 a.m. workout — more accurately, a cycle of three workouts, all back-to-back, starting with skills development and then moving to weight lifting and back to basketball again — that’s arguably the central tenet of his basketball philosophy. Underpinning the whole system, aside from the ascetic, constant repetition, is an invented competition with his future opponents. “I’ve done three workouts before someone even opens their eyes to prepare to work out,” Maxey says. “I just feel like that creates a psychological advantage when I step on the court. I have no reason to fear anybody.”

There’s been little reason to doubt the system. After just two seasons, Maxey has gone from mid-first-round draft pick to not only one of the Sixers’ most important players, but one of the ascendant young stars in the entire NBA. Perhaps more impressively, he’s one of the rare Philadelphia athletes fans have unabashedly and uncritically embraced. Maxey is six-foot-two, not especially imposing in a basketball context, but his arms seem not to have gotten the memo from the rest of him to stop growing. He has the upper body of a linebacker — shoulders so broad they seem at risk of caving in. If certain players carry themselves like tortured philosophers, burdened by the infinite universe of moves they could unleash upon a defender, Maxey plays with something closer to puppy-dog energy: Fetch ball. Drive to hoop. In the first game of last season’s playoffs, Maxey went up against the Toronto Raptors’ forest of long-armed defenders and took a saw to them, scoring 38 points — 21 in the third quarter alone. There were acrobatic layups, parabolic floaters, immaculate threes. At one point, as Maxey lofted a free throw, the entire arena chanted his name.

There was less to cheer about in the next round, as the Sixers meekly unraveled in six games against the Miami Heat. The fans unfurled their frustration at practically everyone, including the suddenly inept James Harden. Only two people seemed exempt: Joel Embiid and Tyrese Maxey.

Photo-illustration by Chris Crisman

For a team that harbored championship aspirations, there was no sugarcoating it: The playoffs were a massive disappointment — a second early defeat in as many years. Still, by almost any metric, the season was an individual success for Maxey. Daryl Morey, the team’s president of basketball operations, says Maxey “absolutely crushed expectations in year two.” Here was a player who spent large chunks of his rookie season on the bench and who, a year later, averaged 17.5 points per game and led the team in minutes during the playoffs. The progression was so rapid, it was as if everyone in the world had fallen asleep while Maxey had been awake and practicing the whole time. He’s still just 21 years old, yet Morey went so far as to identify him as the “absolute key to our title odds,” saying the team’s future championship hopes hinge on “Joel and James being their great selves and Tyrese taking one more step forward.”

Over the summer, Maxey’s name started cropping up in the Kevin Durant trade sweepstakes. The fact that it wasn’t preposterous to suggest Maxey as the central player heading to Brooklyn for Kevin Freaking Durant spoke to his improvement as much as anything. A conversation between Doc Rivers and John Calipari, Maxey’s college coach at Kentucky, at an NBA Hall of Fame event over the summer provided yet another indication. Calipari was nagging Rivers that he’d better not trade Maxey, to which Rivers responded, according to Calipari, “He ain’t going nowhere.” Even Morey, whose job is essentially to never call someone untradable, admitted, “I think I’d have to quit if he ever leaves.” The trade never materialized.

At the post-game press conference after Game 6, the mood was dour. But when Doc Rivers spoke to the media, he couldn’t avoid a touch of optimism: “I think we should celebrate Tyrese; he grew up right in front of your eyes.” When Maxey shuffled up to the podium himself a few minutes later, in a shirt that read MORE SELF LOVE in rainbow lettering, he was more exacting. He proceeded to talk about how if he’d learned one thing about himself that season, it was this: “I just wasn’t good enough.” He was reflecting on the season that had just ended, yes, but it seemed to be a statement about the next season, too — an acknowledgement that his time as precocious overachiever was over. Maxey was, for the first time in his pro career, about to be facing major expectations.

For many NBA players, the aftermath of a playoff defeat is a time to decompress mentally, physically, spiritually — to think about literally anything but basketball after the grueling odyssey that is the NBA’s 82-game season. This had been Maxey’s plan. He told his uncle, Brandon McKay, that he’d sworn off watching the rest of the playoffs. “That lasted, like, a day or two,” McKay says. “He was calling me like, ‘Come over, let’s watch the game.’” A few days after the loss to the Heat, Rivers’s phone rang at one in the morning: Maxey was calling. Maxey, Rivers says, couldn’t stop thinking about the season — what had gone wrong in the playoffs, how Doc had done such a great coaching job and he and the team just didn’t perform well enough. Rivers tried to preach patience. “But he was down,” Rivers says. “He just wanted to win. And I love that.”

After the season, Maxey decamped to Garland to recover for two weeks. He took the first vacation of his life — a week-long trip to Cabo with seven family members, the only time he’d ever been out of the country for non-basketball reasons. “I kind of got to sightsee a little bit and then just sit on the beach, watch the waves crash and let my mind wander,” Maxey says. But his mind seemed to inevitably wander back to the same place: basketball. “I’m big on the work,” he says, “so a week off for me, it’s way too long.”

Maxey’s very first memory in this world is of holding little stuffed basketballs. As a young kid, he had miniature baskets set up on both sides of his bedroom, and when a visitor walked in, there was no escaping getting conscripted into a full-court game of foam-ball one-on-one. Maxey put more than a few holes in the walls over the years, archaeological remnants of attempted dunks.

Maxey grew up on a quiet suburban street with his parents, three sisters and both grandmothers. His father, Tyrone, was a high-school basketball coach. His mother, Denyse, sold insurance. As a three-year-old, Maxey would get up on the bar between the family’s kitchen and living room and cannonball onto the couch. Anytime the family opened the front door to their house, he would sprint through it. “That’s just the kind of kid he was,” Denyse says. “He was always doing something, always jumping around.”

Sports quickly became an outlet for the Maxeys’ hyper-energetic child — and with a dad who’d played collegiately at Washington State and was coaching in Texas, basketball was the obvious choice. In Maxey’s first competitive game, playing as a four-year-old in a rec league against kids two years his senior, he shot the ball every time he touched it. “I told him, ‘Man, nobody’s going to want to play with you!’” Tyrone says. It might not have been the most auspicious start for the son of a point guard, but even at that age, it was clear Maxey had a knack for the game: He was the only one who could dribble.

By the time he was in grade school, the family had oriented its life around his basketball pursuits. He traveled to Detroit, Orlando, Las Vegas, Washington, D.C. He was already playing a miniature NBA schedule: three games on Saturday, three on Sunday, three out of every four weekends, eight months a year.

When he was eight, during a game of one-on-one with his dad, Maxey made his statement of intent: He wanted to be like Dwyane Wade. It was the kind of conversation that has surely transpired thousands of times before between fathers and sons on the basketball court. But two critical factors differentiated this discussion. The first: When his son vocalized his dream, Coach Maxey didn’t laugh it off. He said: “Look, man, you want to be good? You want to be like Dwyane Wade?”

“Yes, Dad.”

“Then you gotta train. Or do you want to just play one-on-one?”

And factor number two: The next day, when Tyrese got to the gym, he didn’t ask to play one-on-one. He said he wanted to train.

So they trained. Tyrone compiled videos of players like Kyrie Irving and Steph Curry and taught Tyrese their moves. He showed Tyrese how to improve his handling by dribbling two balls at once. He made Tyrese practice shooting across the court. Made him practice jab-steps. Dribble-drives. On Thursdays, as the family drove to tournaments across the country, Tyrone was already insisting his son get “locked in.” No video games, no nothing, just visualization of the task at hand. Tyrone would coach Tyrese during the game, then spend the drive home critiquing. Then they’d watch film when they got home. “It never stopped,” Denyse says.

The first time Tyrone Maxey allowed himself to think the fantastical thought that his son might be good enough to play in the NBA came when Tyrese was in fifth grade. Somewhere in the first quarter, he broke his left index finger — and went on to score 45 points. Still, Tyrone was wary: “I’ve seen talent, and some guys don’t make it.”

In 2017, when Maxey got invited to the NBA Top 100 Camp — a national proving ground for many of the league’s best prospects, including eventual players Cole Anthony and Immanuel Quickley — Tyrone was still guarded. “We would go to all these workshops as parents, and they were talking about, ‘Oh, we gotta treat these boys like pros, we gotta take care of their body.’ I’m thinking to myself, ‘Y’all talking about pros? This kid is a sophomore in high school!’”

Tyrese himself harbored no such hesitation. In high school, his Instagram handle was “ballislife_maxey,” and you get the feeling it was an earnest statement of belief. (One of his posts, from 2015, is an screenshot of a text message reading “I wanna be in love

There are three things everybody mentions when you talk about Tyrese Maxey: his pure, absolute love for the game of basketball; his freakish work ethic; and his equally freakish affability and happiness. These are often presented as discrete characteristics, though it wouldn’t be unreasonable to suggest the latter two follow from that first, most elemental trait. It’s precisely because he loves basketball so much that he gets to the gym every morning at 6 a.m. It’s precisely because he loves basketball that he’s happy almost all the time. (And it is almost all the time, according to McKay. “It’s just his perspective,” he says. “He only sees the positive in things.”)

Here’s a typical Maxey quote: “I have this joy about playing basketball. So I’m extremely focused, extremely competitive, and I’m out there having the time of my life. I get to do what I love every single day, and it’s a blessing.” By his own admission, his off-court interests border on generic. He spends his downtime watching Marvel movies and playing with his dog, a cane corso named Apollo. He doesn’t drink and rarely parties. He calls his parents multiple times a day and is so close to his family that he’s spent his first two years as a professional living with McKay, who, at 38, is like an older brother. “I really have a simple life,” Maxey says. “I’m not anybody extravagant.” This isn’t mere self-effacement, according to McKay. “All the kid literally wants to do is play basketball,” he says. “We’re boring, okay?”

Descriptions of Maxey’s personality approach the hagiographic. “Smiling, happy, full of life,” says McKay. Doc Rivers says there are some players who “bring in sunshine” when they walk into the gym, while others bring a “cloud fucking behind them.” Maxey, he says, “is definitely a sunshine guy. He’s just a pure kid. And I hope the NBA never takes that away.” His agent, Rich Paul, who’s encountered plenty of players with a “you-should-be-calling-me-type mentality,” says Maxey routinely calls him out of the blue to check in, instead of the other way around.

Maxey’s chipper demeanor, however, obscures the challenging and turbulent past three years of his life. In the summer of 2019, before he was set to begin school at Kentucky, Maxey was at a basketball camp when Tyrone suffered a major stroke. As Tyrone was rushed to the hospital, Tyrese was the only family member present and had to give the word on whether doctors should try a risky procedure to reverse the effects of the stroke. “I had to make some decisions that most 18-year-olds probably didn’t have to make, but you know, it’s life,” he says. When Maxey played his first-ever collegiate game, a sensational debut at Madison Square Garden against top-ranked Michigan State in which he scored 26 points, his dad couldn’t attend. It was the first game he’d missed in years. By the middle of Maxey’s freshman year, Tyrone had recovered and moved to Lexington, alongside McKay, to be close to Tyrese. The family eased into its old routines, with Tyrone and McKay fixtures at every game and, afterwards, Tyrese coming over to watch and then rewatch the game he’d just played in, his dad coaching him up on what he could have done differently.

By the spring of 2020, normalcy seemed to be setting in. And then: pandemic. Maxey’s collegiate career unceremoniously ended on a Thursday in March, in Nashville. His family had just made the 10-hour drive to watch the SEC Tournament, only to see it canceled. The NCAA tournament: nixed, too. As a freshman, Maxey had been one of the best players on the eighth-ranked team in the country. The tournament was what every college basketball player, whether you played for Kentucky or Grand Canyon University, dreamed of. For Maxey, it was also a chance to showcase his skills ahead of the NBA draft. Instead, he found himself clearing his dorm room and returning home to Texas. Just like that, college was over.

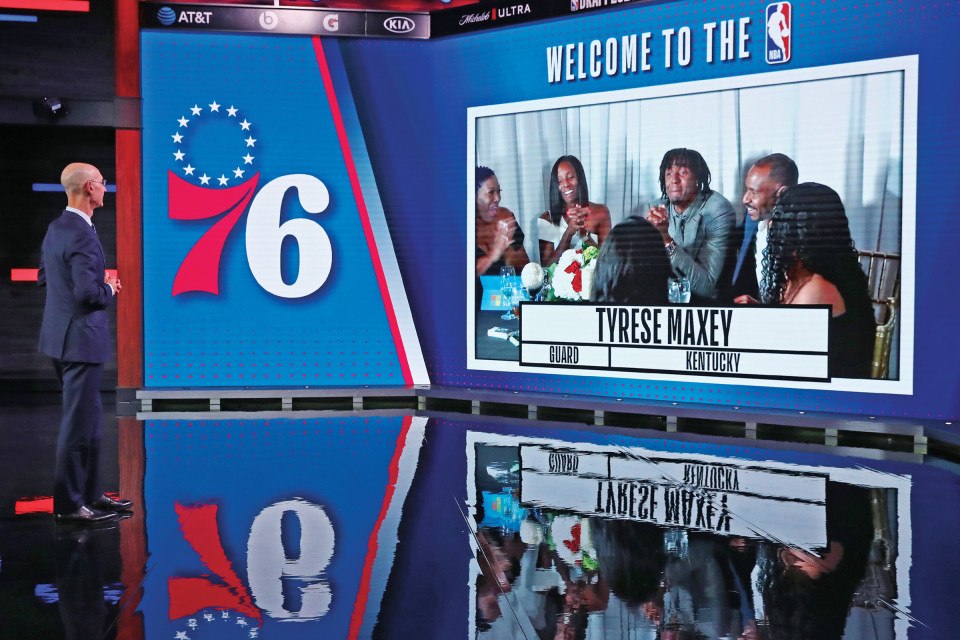

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver watches Maxey’s reaction to being drafted in November 2020. / Photograph by Nathaniel S. Butler/Getty Images

Maxey was projected to be a top 14 lottery pick, but the season at Kentucky had been mixed. His three-point shot, normally a strength, had been hot and cold. There were questions about his ball-handling and playmaking. On draft night, Maxey watched on TV as the picks ticked by: first, fifth, 10th, 15th, 20th. Behind the scenes, Calipari was calling everyone who would listen, including Doc Rivers, saying, “If he slips to you, you better jump so fast.” (Calipari blames the canceled NCAA tournament for Maxey’s slide in the draft: “There’s no way Philly would have got him. No way. He’d have been a top 10 or 12 pick.”) Finally, with the 21st pick, Maxey heard his name called. Instead of walking across the stage in New York City to shake commissioner Adam Silver’s hand, though, he sat at home in Garland with his parents — another crowning moment snatched by the pandemic.

COVID decimated time for almost everyone, bringing it to a halt. But for Maxey, it had the opposite effect — without any of those capstone memories to grab, it was as if someone was pushing a fast-forward button. “Life changed so fast,” he says. “In three years, it went from being in high school to now I’m traveling, sitting in front of Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons and playing with those guys. It moves so quickly.”

Twenty-first overall picks aren’t supposed to make an impact on a playoff team. Not on a team coached by Doc Rivers, who’s known to make young players earn their minutes, and especially not a young player like Maxey, who didn’t even have a full college experience. “You can easily make the case he came straight out of high school,” Rivers says.

When Daryl Morey met his new draftee, it quickly became clear he had an agreeable personality on his hands. Morey didn’t necessarily consider that a good thing. “When a first interaction goes very positive, that can cut both ways for me,” he says. “A lot of times, the people who are good in social situations, they often are not as good of workers.” According to Morey, a lot of “delusional players” “stop improving because they think they’re already there; they already have the money; they already have the lifestyle.” It didn’t take long, however, for Maxey’s workout habits to assuage any doubts. Maxey saw the gap between his current and imagined future self and had the discipline to close it. He was at the gym so often that Rivers had to institute blackout dates — what he came to think of as the “Tyrese Maxey clause.” He would routinely tell Maxey, “You are forbidden from going into the gym.” In a town where one of the most infamous sports quotes questions the very purpose of “Practice?,” Maxey can’t get enough of it.

Maxey was quick to impress his new teammates at his first training camp. “After the first day, I was like, ‘Yo, this kid can go, he can really hoop,’” Sixers forward Tobias Harris recalls. One day, Maxey played with the third-string players in a pick-and-roll drill and beat the veterans. As NBA achievements go, it was a small one, but it helped remove any sense of being starstruck. Maxey thought to himself, “Okay, maybe this isn’t as bad or as hard as I thought it would be.”

At the end of that training camp, Rivers assembled his coaching staff and made a surprising prediction: Tyrese Maxey will be playing minutes for us by the end of the year. “I was in the strong minority,” Rivers says, laughing. “I think it was me vs. all our coaches. None of them saw that.”

Maxey’s first season was bumpy. He played in unpredictable bursts: 20 minutes here, 10 minutes there. Then, in January, before a game against the Denver Nuggets, almost the entire team caught COVID — the starting lineup that day was Danny Green, Dwight Howard, Isaiah Joe, Maxey, and someone named Dakota Mathias. Maxey took advantage, scoring 39 points in more than 40 minutes. It seemed this was finally a case of the pandemic handing him an opportunity rather than snatching one away. But there was a catch: What should have been a roaring coming-out party was muted. There were no fans in the stands to witness the performance in person.

When the COVID outbreak subsided, Maxey returned to the bench. In February, in a game against the Sacramento Kings, he didn’t get off it — his first time ever not touching the court in a game. He sought a positive spin — “It brings your ego back down to humility” — but the lack of playing time was frustrating. Maxey would at times complain to Harris that on a lesser team, he’d get to showcase his talent. To which Harris replied, “Yeah, you would, but you got to trust this whole path that you’re on right now — you’re on a winning team, we’re going to the playoffs, and you’re going to get your opportunity.”

Sure enough, when the playoffs came around, Maxey found himself on the court — and once he got there, he made a compelling case that he shouldn’t leave. In Game 2 of the opening series against the Washington Wizards, the Sixers had a 14-point lead going into the fourth quarter. Maxey came in and scored 10 points. “I started to realize, like, man, I can really help us maybe win in the playoffs like Coach Doc kept saying,” he says.

Of course, that season ended with The Dunk That Wasn’t — Ben Simmons passing to Matisse Thybulle instead of taking the open dunk in the fourth quarter of Game 7 in the second round, against the Atlanta Hawks. As the season wound down, Maxey wasn’t on many people’s minds. There were more pressing and dramatic questions at hand. (Among them: Why, Ben? Why? Why? Why?) Then, at the end of that off-season, as Maxey entered his second year, Rivers reconvened his coaches. He made another pronouncement: “Tyrese Maxey is playing big minutes next year.”

Tyrese Maxey shooting during Game 1 of last season’s playoff series vs. Toronto. / Photograph by Tim Nwachukwu/Getty Images

It had become increasingly easy to bet on Maxey. He had charmed most everyone in the organization by then. His teammates can barely remember him ever having a bad day. “Never seen him get mad,” Joel Embiid proclaims. “I don’t know if I’ve ever seen him rattled,” James Harden says. He seems to be physically incapable of not smiling, and he plays basketball with the excitement of a kid reporting to his first day of kindergarten. Once, when Toronto Raptors guard Fred VanVleet accused him of flopping — the kind of allegation that should produce at least a stink-eye in response — Maxey laughed and shot back, grinning: “It’s because I’m weak!”

That smile — with all the tumult he’s been through in the past three years, it can be tempting to wonder: Is it legit? Maxey, seemingly aware of that line of inquiry, has publicly insisted it’s not a front. Last Christmas Eve, his rental house in New Jersey caught fire while his family was inside, cooking dinner. His clothes: gone. His car: destroyed. His family was safe, though, and on New Year’s Eve, Maxey posted a series of joyful-looking photos on Instagram. The caption read: “I just wanted to let everyone know my family and I are safe. … The last week has been rough but a lot of people have helped us through this and helped me keep a smile on my face! That smile is not a cover up, it’s real because I’m extremely blessed to be here on earth and have great people around me. I’m posting this so y’all understand how blessed I am to be here along with my family! 2021 was full of blessings and new opportunities! Bigger and better things to come in 2022!!”

In August, Maxey returned to Kentucky to host a free basketball camp. Just three years before, he’d been doing sprints across Kentucky’s practice court, getting yelled at by Coach Calipari. Now here he was, still galloping around — in a gray shirt that said TYRESE MAXEY BASKETBALL CAMP on the front. In the far-off future, after his basketball career is finished, Maxey envisions pursuing commentary or acting, although if neither pans out, he could land a sure-fire gig as a camp counselor. For hours, he bounded around with as much energy as the grade-school attendees, running between two practice gyms where kids worked on drills and scrimmaged in games of five-on-five. Whenever Maxey joined a scrimmage, he ran up and down the court, blocking shots, dunking, dribbling through five kids at once, and passing out what must have approached the Lexington single-day record for high fives. At one point, in the hallway between the gyms, Maxey passed a mural showing former Kentucky stars — John Wall, Anthony Davis, Jamal Murray, Tyler Herro. Someone noted that Maxey was nowhere to be found, to which he said, cheerily and not missing a beat, “I’ll never be on that wall — that’s for lottery picks!” He didn’t sit down once in more than three hours.

Tyrese Maxey with kids at his Garland camp in August / Photograph by Darrell Ann/Klutch Sports Group

Maxey had arrived in Kentucky the day before from Dallas. After a summer of travel — working out in Texas for a month, then a month and a half working out in Los Angeles with LeBron James (who, upon learning Maxey liked to get to the gym at 6 a.m., made a point, on their first day working out together, to be in the middle of a bench-press when Maxey walked through the door), then running his camps in Garland, Philadelphia and Lexington — Maxey was finally gearing up for the coming season. He was doing his best to ignore the Kevin Durant trade rumors — “It doesn’t really bother me anymore,” he said — and later that month, the Nets would announce they were no longer trading the star.

A few weeks after the camp, Maxey was back in Philadelphia. On one of his first nights in town, he went to a Phillies game and spent an inning in the booth with John Kruk. On his way down to the field, fans caught a glimpse of him and began chanting: “MAXEY! MAXEY! MAXEY!”

This wasn’t exactly new for Maxey. As early as high school, kids from other schools had been coming to watch his games and ask for selfies. He’s constantly stopped for photographs — in Lexington, there were requests from a guest in the hotel lobby who was from Philly, then from a local businessman Maxey had dinner with. Each time, he happily obliges. “People say hi in the streets; it is what it is, and I appreciate it,” Maxey says. “But I mean, I’m used to it, I’m blessed.” He’s begun wearing a hoodie at the airport in a (mostly futile) attempt to blend in.

Still, something about the reception at the Phillies game felt different. It’s one thing for delirious fans to chant an athlete’s name as he does something enthralling in the heat of a game. To chant for him on sight, as the Phillies crowd was doing, was something else. Maxey had his first true breakout season, but between the loss in the playoffs and the fact he’d spent most of the off-season away from Philly, there had been no time to celebrate. Now he was taking a victory lap, one that was all the more sweet considering he’d been through an interrupted college experience, a lost NCAA tournament, an at-home NBA draft, a house fire, and a world-changing pandemic. But the adulation doesn’t come free. It has to be earned anew every time he steps on the court. Just imagine, God forbid, if Maxey doesn’t live up to expectations, while the corpse that’s Ben Simmons mystically revives in Brooklyn alongside Durant. The way the city feels about Maxey, and the Durant trade that wasn’t, could end up very different.

For the time being, though, Maxey is in the midst of a public shift: from role player to superstar. If he feels it, he isn’t letting on. “I don’t think I’ve changed at all,” he says. “I’m the same.” Watching him descend the steps, his name floating in the summer air, an entire sea of hands stretching toward him like a tide, it was tempting to reach a slightly different conclusion: Tyrese Maxey may not have changed, but everything around him has.

Published as “The Importance of Being Maxey” in the November 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.