The Wild, Wild West of Philly’s Food Influencer Scene

Philly diners are spending their dollars based on recommendations from TikTok and Instagram. It’s the democratization of food criticism. What could possibly go wrong?

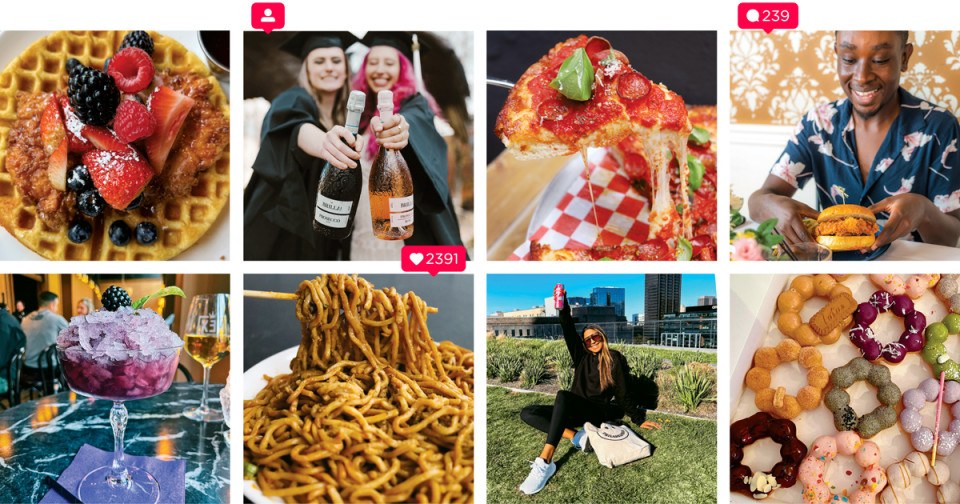

Clockwise from top left: Chicken and waffles at City Winery (by Josh Moore); the @PhillyFoodLadies at their Temple graduation (courtesy of PhillyFoodLadies); Chicago-style pizza at Hook & Master (by Josh Moore); Josh Moore at Southern Cross (by Josh Pellegrini); the goods at Mochi Ring Donut (by PhillyFoodLadies); Cassandra Matthews at Cira Green (courtesy of Cassandra Matthews); dan dan noodles at Han Dynasty (by Josh Moore); a cocktail at Rex at the Royal (by PhillyFoodLadies).

On May 4, 2022, Josh Moore uploaded a seven-second video to TikTok, just like he does every few days. The clip begins as a sped-up rendition of Daft Punk’s “Around the World” plays. The screen fills with waves rippling in the Delaware River beneath the Ben Franklin Bridge. A text box reads: “Things to do in Philly, Liberty Point.” Next, a southern-facing view of the river reveals the part of the sky where the sun has already oozed to pink. Cut to a frozen tie-dye swirl of red and yellow booze in a plastic cup, twisting slowly. Then a cheesesteak held aloft, all blotchy and spotted with provolone goo. “Great vibes, drinks, & food right on the Delaware River,” a new text box declares. “The ultimate summer destination in Philly!”

Moore’s Liberty Point video has been viewed 12,400 times on TikTok, the popular social media app that lets users upload short videos paired with trending audio clips. The post is one of hundreds of similar videos capturing the newly opened waterfront spot, which is said to be the largest restaurant in Philadelphia history. “Who’s excited to check out Liberty Point on the Delaware River Waterfront in Philly?” Moore’s caption reads. A commenter on the post writes: “I’m there.” Another chimes in: “I see all the Philly influencers were at the same spot.”

Watch on TikTok

In 2022, Philadelphians are discovering local restaurants on TikTok and Instagram. These diners, who typically land somewhere in the 18-to-34 age category, wade through videos of restaurant patios adorned with perky flowers and happy hours offering $6 frozen margaritas in search of their next Friday night out. They are shepherded to small businesses not by restaurant critics or journalists, but by a new, democratized breed of influencer. Armed with handheld lights and looping autotuned background sounds, TikTok and Instagram restaurant influencers are reaching hungry new audiences and encouraging younger generations of diners to explore their city at a time when all restaurants — even the longtime classics — are eager for customers.

Behind the scenes, though it may not seem obvious, lies a rarely seen reality of food influencers and hospitality PR agencies. In this ecosystem, the ethics of local restaurant coverage brush up against the ethics of paid content production. Video posts are exchanged for free meals — or in some cases thousands of dollars. Work is contingent on positive restaurant experiences, and often, posts are agreed upon before an influencer ever sits down for a meal. Publicists throw grand opening parties with guest lists made up of those they hope will communicate a perfect picture of a restaurant. The world of Philly influencer marketing is new, ever-changing and unregulated. It’s giving power to those who know how to harness it, and it’s messy with questions about the dynamics that exist off-screen. But when you’re scrolling online, you may only catch the part that lights up your phone.

When I meet Josh Moore at Café La Maude in Northern Liberties, we order the same breakfast: a platter with soft scrambled eggs, curly-greasy bacon, white toast, and two hash-brown patties that taste like glam cousins of the frozen variety sold at Trader Joe’s. Moore has agreed to eat with me here sans content production. Had he come to nab food photos and videos for his popular TikTok and Instagram accounts, he says, he might opt for a pancake meal, or maybe a tower of French toast: “When I go to a place for content creation, I don’t order what I actually want to eat. I order what I think will do well.’”

View this post on Instagram

Online, Moore goes by @josheatsphilly — a local food influencer interested in tacos, cocktails colored so vividly they might have electricity running through them, and miraculously non-drippy ice-cream cones. In real life, he works a finance job. He’s sunny-sweet, Jersey-born, earnest and professional. He talks about his social media side gig with as much gravitas as any CEO or business owner characterizing an enterprise.

In 2011, Moore was as early to join Instagram as he would be to download TikTok years later. He created his account as a brand-new Philadelphian, hoping to make friends by going out to as many restaurants and bars as he could, posting about his experiences, and fostering online connections as he shared his world in photos. One day, Moore’s brother gave him the idea to treat Instagram like a personal blog. It was then that Moore began chronicling his favorite restaurant meals around Philly via still images tinted with sepia filters (as was the custom). Soon enough, hordes of loyal strangers relied on the account, often sending direct messages asking for his honest restaurant opinions, or whether he could recommend a place for a date night in Center City. In 2019 and 2020, Moore pivoted his social strategy to prioritize video, allowing him to tell the story of a restaurant in ways a single image of a dish never could. Suddenly, restaurants — new ones and tenured spots, all struggling to fill seats in the age of COVID — came knocking.

“Because of the following I’ve amassed, I’ve had a lot of restaurants reach out to me,” Moore says, “and they’re like, ‘Hey, can you come and feature us, we’d love to have you.’” Last spring, a restaurant owner Moore prefers not to identify contacted him seeking advice. The owner had recently opened a sushi spot on Market Street and was anxious to attract customers to its fairly sleepy location. After Moore recommended online exposure, the owner offered a complimentary meal in exchange for a promotional TikTok video and an Instagram Reel on @josheatsphilly. Moore had never visited this particular restaurant before he agreed to work with its owner. He showed up, ate his sushi and shot his footage, and had a consult with the owner about how best to present the food to his @josheatsphilly audiences on TikTok and Instagram. (Moore has 25,700 followers on TikTok and 72,800 followers on Instagram). Moore’s TikTok video of the meal accumulated around 9,500 views.

Fellow Philly influencer Christina Mitchell says that collaborating with a restaurant on a social media post and receiving free meals carries inherent expectations, some of which go unspoken. “If you’re actually being invited,” she explains, “there is more pressure to make the video better.” Sometimes, these pressures are contractual. “I won’t say what specific restaurant this is,” Mitchell’s dining partner, Rebecca Neckritz, tells me, “but we were invited to a restaurant and then given a list of words we couldn’t say about the restaurant. I remember we couldn’t say the phrase ‘meat sweats.’”

Neckritz and Mitchell are behind the local TikTok and Instagram accounts @PhillyFoodLadies. After the two were assigned as first-year roommates at Temple University in 2017, it didn’t take long for them to find something in common: Both grew up in the Philly area wanting to be food critics. As a kid, Neckritz was an obsessive reader of Craig LaBan’s restaurant reviews in the Inquirer. “I want that to be my job,” she recalls thinking. “But there’s only one of them, and he already has the job.” During their first year in college, the two roomies created a shared food Instagram account with long diary-style captions, just for fun — a way to keep track of their various Philly meals and tell friends about them. Then, one day, their favorite Vietnamese spot on campus offered them free pho if they posted a photo on their account. “We were like 18 years old, and we were very excited about this,” Neckritz says. “I remember they were the first ones to ever offer us anything in return for posting.”

When regular campus social life dried up during the pandemic, Neckritz and Mitchell refocused their energy into growing their Instagram account and newly created TikTok profile. They set out on a mission to highlight Philly’s best happy-hour deals, rooftop views, and bars with unique elements like mini golf or board games. They strategically followed local restaurants and other food influencers online in hopes of getting the coveted follow-back. They reached out to Philly businesses for collaborations and were quickly inundated with free products in the mail — everything from ice cream to cold-brew concentrate. Eventually, their online community expanded beyond its initial Temple reach. When we spoke this spring, the @PhillyFoodLadies TikTok and Instagram accounts had grown by more than 15,000 followers in 2022 alone.

View this post on Instagram

Though both women wanted to be food critics in childhood, neither considers herself a critic now — not even with a following of Philadelphians watching their restaurant recommendations. The distinction between online food influencer and restaurant critic is hairier today than most critics probably would like to admit. When we discuss the topic, Mitchell and Neckritz take the title “critic” literally, pointing out that they’re not critics because they only post positive reviews. These days, though, restaurant reviews largely follow the same uplifting-takes-only model as the influencer’s work. The key distinction between restaurant influencer and restaurant critic has everything to do with payment.

While Mitchell and Neckritz say they often receive free meals in exchange for creating online content recommending restaurants, they’ve also been paid for their work by local restaurants, big brands like Dunkin’, and the Center City District, for coverage of Restaurant Week. Their ambitions for the accounts have little to do with cash flow, however, since their @PhillyFoodLadies income isn’t currently “self-sustaining” and they’ve both accepted full-time jobs after graduating from Temple earlier this year. (Mitchell is a public health researcher, and Neckritz works in social media marketing.) “Our goal is to uplift small businesses,” Neckritz says. “We want to help out restaurants.” The money they’ve made through influencing mostly comes via working with big brands rather than restaurants themselves. “You need a lot of followers to make this into an actual full-time job — at least a couple hundred thousand,” Mitchell says. At press time, the two women had 15,400 followers on TikTok and 26,300 followers on Instagram.

Because influencer marketing is relatively new, there are few standards when it comes to payment for work, and per-video rates in Philly range widely. “I’ve heard people say their rate is $200,” Mitchell says. “I’ve heard other people say their rate is $1,000 per video.” The Philly Food Ladies have only been paid “a couple of times” by local restaurants. They tell me that those eager to work with influencers are typically smaller businesses looking to boost their customer bases and can’t always afford to pay in cash rather than free food.

Both Moore and the Philly Food Ladies are clear that not all the Philly restaurants featured on their accounts invite them in for free meals or paid content creation. “I think there’s this misconception that influencers get everything for free,” Moore says. “Some people see the number of followers I have, and I think they just assume I get everything for free and that I’m getting paid to post, and that’s not the case.” The local businesses that Moore promotes organically — that is, without complimentary meals, event invitations or payment involved — don’t know he’s coming. He often pops into restaurants with his ring light — a small handheld device that illuminates the table and lends a high-contrast, flashy quality to the footage — in tow. For those visits, Moore typically requests a table in a dark corner where he won’t bother anyone. He’s used to being yelled at by other diners: “I’ve had people glare at me. This one lady was like, ‘You’re disturbing my day.’ I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m working right now.’”

Recommending restaurants that he isn’t being paid to promote allows Moore to “maintain authenticity” on his account, he says. He describes authenticity, in part, as showcasing his identity as a Black queer man and promoting restaurants run by people who align with his background. He notes that he’s still working through the ethical balance of posting about restaurants he visits on his own (and wholeheartedly approves of) and videos that result from restaurants offering to work with him for free food or compensation. Moore has never been invited to a restaurant, received a complimentary meal, and then decided not to post a TikTok or Instagram Reel — even if the restaurant experience has its bumps. When the food tastes great but the ambience or service isn’t commendable, Moore says, he’ll feature the meal on his page and write something of a disclaimer to his online audience. (“Just be aware you might have to wait, things get really busy there.”) If the reverse is true — if service goes off without a hitch but the food disappoints — Moore will choose a dish he likes and focus his energy there.

Taking payments from certain restaurants in exchange for content — in addition to receiving free food — further complicates the overall transparency of Moore’s page authenticity: “I personally wouldn’t feel comfortable saying to, like, Café La Maude, ‘Hey, pay me $500 so I can post a Reel.’ I can’t expect that from every single restaurant, for one.” If a restaurant does compensate him for a post, Moore says, he tries to offer an additional service — social media consulting, say, or photos he takes with his professional camera rather than his iPhone. “Influencer marketing is still the wild, wild West,” he says. “It’s still so new, especially here in Philadelphia, where I feel like not everyone gets it yet. So it’s hard to say to restaurants, ‘Here’s my rate,’ and then the next day post something for a restaurant that didn’t pay me. What value is the restaurant that paid you getting?”

Moore says that when local PR reps reach out to him about an invitation, they seldom ask about rates: “I think from their perspective, they’re working with hundreds of influencers in the city. If I say no, someone else is going to say yes.” When it’s an individual restaurant seeking exposure, he says, it’s different — “I feel like they want me, they want my story, they want my storytelling. I feel like it’s a more personal connection.”

The influencers in this story all agree that a viewer is more likely to engage with a restaurant video that appears to be coming from a heartfelt place of recommendation rather than one that reads like a restaurant ad — even if that video is quite literally an ad without the audience knowing it. (Instagram’s and TikTok’s branded content policies require users to toggle on a paid partnership label whenever posting branded content. Instagram defines branded content as “a creator or publisher’s content that features or is influenced by a business partner for an exchange of value.” In practice, these rules are rarely followed by Philadelphia influencers sharing videos about free meals or paid restaurant work. For instance, Moore’s TikTok of the sushi place doesn’t disclose that it’s promotional content, even though he notes that his Wawa Instagram Reels are ads in their captions.) According to these influencers, their most-watched videos on TikTok and Instagram Reels are for hyper-local, visually exciting unique-to-Philly spots.

Back in the mid-aughts, Luis Tuz discovered he had a talent. Tuz was working as a server at Tequilas Restaurant in Center City and realized he could balance a cocktail atop his head and deliver it to a table without a single spill. Even before the dawn of viral TikToks and Reels, regulars loved Tuz’s cocktail trick. Two decades later, that trick is bringing a new, younger customer base to the restaurant, Tequilas owner David Suro-Piñera says: “People say, you know, obviously they saw that on social media, or their friends told them about it. They ask for it: ‘We hear there are some servers that bring the cocktails on their heads.’”

View this post on Instagram

Suro-Piñera has owned the Mexican restaurant since the day it opened in 1986. It’s set in a historic building, with architectural details that date back to the 1860s. Suro-Piñera and his kids, David Jr., Elisa and Dan Marcos, now run the business together, with Elisa helping out with bookkeeping and reaching out to influencers to invite them to visit. Suro-Piñera says the team doesn’t currently pay any influencers to create content: “Yeah, we don’t see the need yet.” They will occasionally comp a round of drinks or a couple of appetizers for those with social media followings.

Suro-Piñera will be the first to tell you he doesn’t quite understand social media. But he’s got no complaints about the new diners finding his business through TikTok and Instagram videos of his servers carrying cocktails on their heads. “It’s something that adds to the casual, very unique atmosphere of the restaurant,” he says. “We are a formal-dining, tablecloth restaurant. But we still have fun.” Suro-Piñera and his team recently redesigned the interior, in part to appeal to new generations of customers. “It’s very interesting,” he says, “to see the social media really help us present that to this new, young audience.” His happy hours draw in the crowds, but slinging discounted drinks isn’t always profitable. Suro-Piñera says it’s worth it to get younger customers in the door, since they might order food or come back again.

Kory Aversa thinks about influencers 24/7. He thinks about how they post, who they are, which ones are receiving invites to his parties and which ones aren’t. Aversa runs a local public-relations company, Aversa PR & Events, that hosts more “media and VIP” events at local restaurants than just about any competitor in the market. According to its website, Aversa PR works with some 125 local clients, including Dim Sum House, the Garces Group and Uptown Beer Garden.

Aversa’s interest in social media influencers increased “5,000-fold,” he says, when TikTok and Reels gained traction in 2020. Early in the pandemic, he saw an emerging use for people who were active on the platforms. “The media outlets sort of shifted gears,” Aversa says. “They were covering more important and larger pandemic topics.” This left a gap in what he calls “micro-stories,” or reporting on individual restaurants’ offerings: a new brunch, a revamped happy hour, an opening. Influencers on TikTok and Instagram filled that media void for Aversa PR. They could capture a restaurant’s frozen margarita or spacious outdoor patio more dynamically than a press release ever could, particularly in the age of what Aversa describes as “vibe dining.” A 10-second TikTok of a new restaurant shows how diners are dressing or interacting — even what the bathroom looks like. “These days,” Aversa says, “you literally could know every single thing about a restaurant before you get in.”

Soon enough, Aversa began inviting Philly influencers to client restaurants’ parties so they could capture content before the public got to check the spots out. “PR parties used to be more media-based prior to the pandemic,” he says. “Now we have clients that, you know, they want their media, but they’re separating it where media might come on a different day or are treated differently. There are entire events that are just for influencers and content creators.” Aversa might invite 100 influencers to a single event — and each invitation comes with directives about posting. Some are written down; some aren’t.

Watch on TikTok

Influencers who attend Aversa PR events are expected to post one grid post and three stories at minimum. Those guidelines are explained before the event, Aversa says: “If you’re coming to this event and you like it and enjoy it and you want to share it, here’s what we’re looking for.” (These party-posting parameters aren’t unique to Aversa PR events. This magazine hosted an influencer event over the summer; local influencers attended for free and were encouraged to share the experience via stories, posts or both.) If an influencer isn’t impressed by an event or a meal, Aversa wants to hear about it privately rather than see the sentiment expressed online: “Let’s learn from it. Let’s fix what’s wrong, and let’s have you back another time.” He says he isn’t shy about changing up the guest list. In one instance, Aversa recalls dropping an influencer after she failed to adequately describe an “authentic chip” at a Mexican restaurant. He says she posted a TikTok describing her distaste for the chip rather than providing context and education about it that the restaurant staff had given her during her meal.

Despite the control Aversa attempts to exert over influencers’ content, he considers them collaborators rather than contractors: “I’d say we’re partnering with them.” In less than five percent of cases, he pays influencers to attend events or for TikTok or Instagram posts. “I want them to come because they love food, they feel passionate about it,” he says. “This goes to the Kory TikTok side of me and being an influencer myself. I want people like me, like Philly Publicist.”

That would be Aversa’s personal TikTok account. @PhillyPublicist just happens to be responsible for the most viewed TikTok video in Philadelphia history — a clip of two hippopotamuses catching pumpkins in their mouths at the Zoo that went viral in 2021, with 54.4 million plays. He has 97,800 followers on his personal TikTok account — more than twice as many as Moore and the Philly Food Ladies combined. In addition to posting videos of his own restaurant visits and excursions around town, he uses his account to promote the restaurant clients for which he does PR work. He also uses the account to play PR defense. In July, a Philly ride-share driver posted a TikTok relaying an allegation he’d heard from one of his riders: The rider’s boyfriend had recently been roofied at a popular restaurant. The ride-share driver called out the restaurant by name, and Aversa used his @PhillyPublicist account to dispute the accusation, commenting, “You’re causing drama against a business.” He didn’t mention that he was working for the restaurant.

Before Liberty Point debuted outside the Independence Seaport Museum in May, FCM Hospitality Group and owner Avram Hornik hired Aversa PR to ensure a splashy opening full of online buzz. Liberty Point was to be billed as Philadelphia’s largest restaurant to date, capable of seating 1,400 people at a time. “The new outdoor-indoor concept features three main levels, five bars, food, drink, live entertainment, beautiful landscaping, lush plants, blooming flowers, unique vibes and the best views of the waterfront,” an Aversa press release from May 4th reads. Months prior to the official press release, Aversa posted a TikTok on his personal account publicizing the upcoming restaurant. It shows him on the ground floor of Liberty Point with Dua Lipa’s “Love Again” playing as text flashes above his head: “When you are about to announce another brand new restaurant and it’s the biggest one in Philadelphia history. Here we go all again.” In the video’s comment section, Aversa included a link for viewers to apply to work at Liberty Point, which in turn attracted more than 50 staff applications. Elsewhere in the comment section, he pinned a message encouraging viewers to enter a contest to win tickets to Liberty Point’s media party, making sure to publicly respond to specific influencers’ comments that they should watch for invites coming soon. “Best party ever!” he wrote. “Stay tuned!”

Watch on TikTok

The difference between the influencers Aversa invites to make content for his clients and @PhillyPublicist, or the man behind it, anyway, is that Aversa is being compensated to do his job as a publicist while reaping the social benefits of being an influencer. “It’s a great way to get out the word about my clients in a different way, and I love being able to share the news of all these openings and give people an insider view,” he says.

The power Aversa yields over influencers in Philadelphia relies solely on those people wanting to play by his rules. Many of them do, in fact, in order to stay on the guest list for his parties. Cassandra Matthews doesn’t.

Not long ago, Matthews told Aversa she had a negative experience during a complimentary visit to one of his repped restaurants and was uncomfortable posting about the meal on her popular TikTok or Instagram accounts, @cass_andthecity. As a result, Matthews says, she was taken off the Aversa PR invite list. She adds that Aversa didn’t warn her or communicate why she’d been dropped. Aversa disputes this claim, saying, “We collaborated with her on a partnership and we hadn’t heard back. We gave her space to finish the content, and we communicated several times along the way, in writing and on the phone. As soon as the partnership was finished, we regrouped and moved forward with opportunities that were a fit for her and our clients.”

In the early days of the pandemic — two years before she had heard of Kory Aversa — Matthews was at home, just like everybody else. As she watched the world shut down, her steady gig as the assistant director of a local gymnastics gym seemed increasingly less promising. Matthews clung to social media for distraction and connection. She downloaded TikTok and noticed an open lane in Philadelphia for spotlighting restaurants and small businesses: “I saw a couple of New York City TikToks pop up on my page, and I was like, ‘Huh, nobody is doing this in Philly, and there is so much here.’” She decided to try it herself, sharing her Philly life and favorite local spots with anyone who might come scrolling by online.

Matthews began to stitch together sub-30-second montages, driving to local businesses with her mask securely over her face. In one of her earliest posts, from October 2020, she spotlighted the Cheesecake Lady, a small Black-owned Elkins Park bakery run by a mother-daughter duo. The video’s voice-over, paired with a dinging harmony that behaves like a meditative video-game soundtrack, explains that the Cheesecake Lady’s colorful cakes sell out every day the place opens. To get one, you have to show up early and hope for the best. Perfect fodder for TikTok, she thought. Her video about that “hidden gem” has 688,000 views — more than 10 times as many as any other video posted about the business.

Matthews often chooses to amplify Philly restaurants operated by women and people of color, noting ownership details in hashtags and captions. “I was showing things that people might not have known were there,” she says. She identifies as tri-racial — Black, Pacific Islander and white — and speaks openly about her identity on her pages. Following the success of the Cheesecake Lady TikTok, Matthews continued to post videos titled “Favorite Places Around Philly,” bopping to Pizza Jawn in Manayunk and Prince Tea House in Chinatown. Eventually, Instagram Reels joined the party, and she gained a following on both: 170,200 and 82,600 followers, respectively.

Influencing is now Matthews’s primary source of income; she recently retired as captain of the Flyers dance team. She’s signed influencer contracts with Wawa, Dunkin’ and Pepsi, created an LLC, hosted giveaways, and launched her own line of merchandise. “I’m bringing in a higher income than I ever thought I would earn in my life,” she says. A percentage of that income is from local restaurants — restaurants that, she says, “understand there will be an influx of business revenue, social media exposure” from her work. Those restaurants spend on influencer marketing and communications despite thin margins in the business generally.

In February of 2022, the team at Twenty Manning in Rittenhouse contacted Matthews about featuring the restaurant on her feed in hopes she’d highlight the newly redesigned space and a few specialty items on the menu. Twenty Manning certainly wasn’t new to the dining scene — Audrey Claire Taichman opened the joint in 1999, and it was eventually sold to Rob Wasserman in 2018 as part of a restaurant group that includes Rouge and what was once Audrey Claire and is now Charley Dove. Nor did the business revamp its concept. But it was looking to expand its customer base, Matthews says, and to let people know about the remodel.

During that initial ask, Matthews says, the restaurant team didn’t offer to pay her. Matthews fired back: “I knew they had [money]; they have multiple restaurants. And I also knew that they blew me off when I reached out for collaboration in the past.” After about a month of back-and-forth, Twenty Manning agreed to a payment plan: $1,500 for a TikTok post, $1,000 for an Instagram Reel, and $100 per story. When all was said and done, Matthews sent the restaurant group an invoice for $2,700 for a TikTok, a Reel and two stories. (Since then, her rates have gone up.) Matthews was given full creative control over her posts on Twenty Manning, and the meal was comped (She pays a 20 percent tip even when her meals are free.)

Matthews’s Instagram Reel of Twenty Manning, which was shared as a collaboration post between @cass_andthecity and Twenty Manning (meaning it would appear on both pages), accumulated 90,800 views. That figure represents roughly 83,000 more views than every other Reel on Twenty Manning’s page. “It did pretty well on TikTok,” Matthews says — 60,800 views. “You never know with TikTok’s algorithm if things are going to do well or not. I believe their following, like, probably doubled just for my posts about them within 24 hours.”

View this post on Instagram

Twenty Manning hasn’t reached back out to Matthews, though. “They’ve been working with some other foodie influencers since then,” she says. “You never know — if those other people are doing it for free and they like working with them, then they’ll work with them more.”

Matthews believes other influencers should ask for compensation from large restaurant groups that can afford to pay for marketing efforts rather than simply accepting comped meals or gift cards — a form of currency, multiple sources say, that the Starr Restaurant Group is particularly known for offering. “PR has become the middleman for a lot of influencers, especially locally,” she says. “There are some PR companies that I don’t think have our best interests at heart.” Matthews tells me she no longer receives invitations to most PR companies’ events these days.

Beyond the lack of compensation, Matthews generally finds press parties unwelcoming: “Influencing is heavily dominated by white women. … There aren’t many minorities at these events.” From the other side of the screen, the homogeny of those attending these parties is hard for viewers to discern. Just as hard to discern, perhaps, are details regarding which videos are sponsored and which aren’t. In some cases, the fantasy ends when the TikTok does.

The Liberty Point I came to know on TikTok promised a lot: great views of the Delaware River, a pink-orange sunset peeking through the sky. The videos signaled that when I went, I’d be drinking colorful booze and helping myself to sliders and soft pretzels stacked in little mountains.

The Liberty Point I came to know on a hot Tuesday in June exists somewhere between a subdued frat party and an airport lounge with its ceiling lifted off. On the day of my visit, there happened to be a private party on the deck where the bouncer told me the best views live. I ate crab dip that tasted like whitefish salad gone awry. I drank a frozen daiquiri with mango syrup dripping down the sides. My experience was without glamour or side effects of feeling like a VIP at a party. Liberty Point is, after all, a 1,400-seat bar masquerading as a 1,400-seat restaurant, and it would be challenging to feel like a VIP among 1,399 strangers all trying to figure out if their orders of soft pretzels are ready.

As enthusiastically as a TikTok influencer may claim to have found the best dining experience in the city, real restaurant visits carry no guarantees. Meals may vary based on the server’s mood after being denied a wage increase, perhaps, or due to the weather, or maybe to a cook who forgot to properly soak the beans because she was burned out from covering another cook’s shift. (This is in part why formal restaurant reviews are ideally published after multiple visits, though even that system is far from perfect.)

Josh Moore says it’s not uncommon for people to reach out to him about a disconnect between what’s on his TikTok and Philly’s dining reality, where staff shortages run rampant, margins are thin, and vibes can’t always be immaculate. In recent months, he went to an event thrown by a PR company and posted about it. “I had people DM me afterward commenting that, ‘Hey, I went there, the wait was two hours. I had this negative experience,’” he says. He hasn’t nailed down where his responsibility lies when creating videos for public consumption. How could he possibly anticipate someone else’s experience walking into a restaurant months after he did?

In real life, Liberty Point isn’t an apocalyptic disaster. Nor is it guaranteed fun: It’s ultimately an unimaginably large place at which to drink outside in the summertime. I wouldn’t personally suggest spending $20 to park at Penn’s Landing to have drinks there, but you could easily end up at a destination in Philly with worse rum and no view of the Delaware.

As I sipped my daiquiri in an area designated for walk-ins — furthest from the bar but closest to the bathrooms — I noticed the couple next to me take a selfie with the river and a big blue sky in the background. They examined the photo, agreed on their mutual displeasure with the image, and decided to move to a section with better views and try again. Watching them was like temporarily living inside the space between the internet and real life, the one that’s unpredictable, fast-moving, and full of equal amounts of cash and disappointment. You can’t take a video of that space and share it with your followers. You’ll just have to feel it for yourself one day.

Editor’s note: The print version of this story included a typo that changed the meaning of a quote by Kory Aversa. It has been corrected here.

Published as “Under the Influencers” in the September 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.