If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Benjamin Franklin: 45 Things You Never Knew About Philly’s Own Founding Father

In advance of the new Ken Burns documentary, the lowdown on the life and loves of the Philly icon.

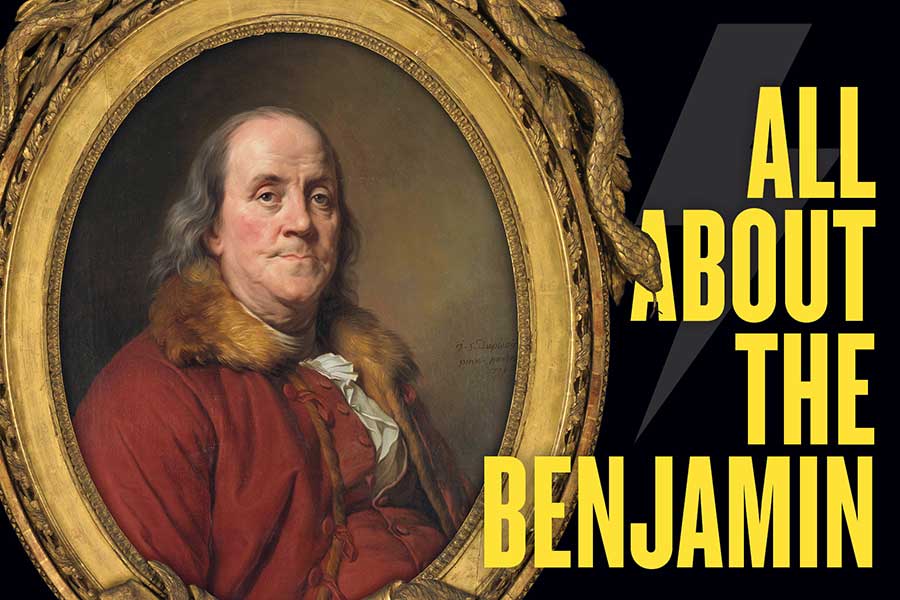

Painting by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis via Metropolitan Museum of Art

This month on WHYY TV 12, PBS.org and the PBS Video app, historical documentarian extraordinaire Ken Burns debuts a new two-part, four-hour production, Ben Franklin, exploring the life and times of this city’s most famous resident (albeit an adoptive one; he was born and raised in Boston and only moved here when … well, just watch the show). Advance reviews of this exploration of the man the Washington Post once called “the most lovable of the Founding Fathers, and perhaps after Lincoln the most beloved of Americans” have been unanimous in their praise. In honor of the occasion — and the polymath genius who inspired it — we hereby present a cornucopia of trivia tidbits about Philly’s favorite son.

1. Benjamin the Muse

Ben Franklin was one of the most frequently painted people of his time. He got so many requests to sit for artists that he once wrote of those sessions, “I am perfectly sick of it. I know nothing so tedious as sitting hours in one fixed position.” One of the largest collections of images of Ben is housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which owns at least 150. The one above, though, lives at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

2. Three Philly Institutions Begun by Ben

You wanna talk about founding fathers? Ben was the brains behind any number of local institutions, including:

- The first volunteer fire company in Philly

- The Library Company of Philadelphia

- The University of Pennsylvania

3. Ben’s Many Aliases

Among the various pseudonyms under which Ben published his voluminous prose: female figures Silence Dogood, Alice Addertongue and Polly Baker, and jaunty Anthony Afterwit and Richard Saunders, a.k.a. Poor Richard, of almanac fame.

4. Ben’s John Hancock

Ben is the only founding papa to sign all four of the most foundational documents of our country: the Declaration of Independence; the Treaty of Amity and Commerce (with France); the Treaty of Paris (between the U.S., England and France); and the U.S. Constitution.

5. Till France Do Us Part

Ben’s marital status was … complicated. That story about Deborah Read laughing when she first saw him coming down the street straight off the boat from Boston, a loaf of bread under each arm? True. And he did move in with Deborah and her widowed mom, and the two young people — he was 17, she 15 — fell in love. But then he went to Europe, and Deborah married another dude, who, it turned out, already had a wife, so she tried to divorce him, but he’d disappeared, so she couldn’t. Then Ben had a baby, not with Deborah. Still, the couple’s common law marriage lasted for many years though they spent much of it apart.

6. Oooh La La! An American in Paris

During the time he spent in France, Ben acquired a reputation as quite the ladies’ man. Hey, what woman could possibly resist such a proto-nerd? Claude-Anne Lopez’s 1966 book Mon Cher Papa: Franklin and the Ladies of Paris recounts his many flirtations and dalliances (that’s him on the riverbank below) and notes that he viewed women “not merely as objects of desire, but as people with a different outlook, with their own contributions to make.” At one celebration, “the prettiest among 300 ladies” was chosen to crown him with a laurel wreath and kiss him. On another occasion, notes an “ecclesiastical friend,” Abbé Martin Lefebvre de la Roche, in his memoir:

When one particular lady, eager for his preference, asked him if he did not care for her more than for the others, he would answer: “Yes, when you are closest to me because of the force of attraction.”

Très charmant, Ben. / Getty Images

7. Ben’s Big Day

His January 17th birthday is shared by a stellar list of famous folks, among them Oprah, Betty White, Muhammad Ali, Michelle Obama, James Earl Jones, Dwyane Wade and Al Capone. Admirable company! The trouble is, that wasn’t really his birthday. He was born on January 6, 1706; a royal adjustment to the calendar in 1752 — September 2nd was followed by September 14th — changed his celebration date.

8. On the Subject of Farts

Frustrated with the frivolous pursuits of much of the scientific establishment of his day, Ben responded to the Royal Academy of Brussels’s call for scientific papers by penning a tongue-in-cheek demand for a deep scientific exploration — a probing, if you will — of, well, farts. “It is universally well known, that in digesting our common food, there is created or produced in the bowels of human creatures, a great quantity of wind,” Franklin wrote at a probably flatulent age 75. “That the permitting this Air to escape and mix with the Atmosphere, is usually offensive to the Company, from the fetid Smell that accompanies it.”

9. Benemies

Though Ben was famously amiable, some people really, really didn’t like him, in particular William Penn’s son Thomas; John Adams, the second U.S. president; and William Smith, the first president of UPenn. Thomas was incensed by Franklin’s attempts to convince the British crown to end his family’s proprietorship over the colony of Pennsylvania. Adams took umbrage at Ben’s easy way with the ladies. As for Smith, he and Franklin clashed over plans for the “College of Philadelphia” they were founding. Franklin urged a utilitarian curriculum, while the highly religious Smith (successfully) argued for one grounded in the classics. Smith was also a stout defender of the Penn family, leading Ben to express his hope that “the Proprietors will be gibbeted up as they deserve to rot and stink in the Nostrils of Posterity”

![]() 10. The Room Where it Didn’t Happen

10. The Room Where it Didn’t Happen

A song sung by Ben was cut (as was his character) from the Broadway musical Hamilton. The Decemberists recorded a version; the chorus goes, “Do you know who the fuck I am? I’m Benjamin fucking Franklin.” We think leaving it out was a mistake.

11. A Tale of Two Bens

After its creation in 1914, the hundred-dollar bill went through very few changes until 1990, when the U.S. Treasury realized something had to be done to prevent counterfeiting of our most valuable circulating currency. The result: security features such as that metallic vertical thread imprinted with “USA” and the “100” to the left of Ben’s portrait. But that wasn’t enough. What you may not realize is that there are now two Ben Franklin portraits on all those C-notes in your wallet. In 1996, Treasury added a second portrait of Ben as a watermark. It’s to the right of the Treasury Department seal, and you can only see it if you hold a bill up to the light and look very closely for the faint image, which is visible from either side of the bill. The feature was updated in the current version, which debuted in 2013, but ne’er-do-wells still somehow manage to knock the suckers off.

12. Ben and the Gulf Stream

A cousin of Ben’s, Timothy Folger, captained a merchant ship that sailed between Great Britain and the Colonies. When Ben inquired why Folger’s ship completed the sail so much more quickly than official British mail ships, Folger noted that British sailors must not have been aware of the existence of the Gulf Stream, which he’d learned of in years spent as a Nantucket whaler. Ben subsequently charted the stream on his journeys to and from Europe, and during the Revolution, he passed his knowledge on to America’s French allies so they could use the warm current to speed their ships.

13. Ben the Belonger

There’s some controversy over whether Ben ever actually said, “We must hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.” What we do know is that Ben was a joiner. He really dug hanging with his crew. Here’s a partial list of the many, many civic and fraternal orgs of which he was a member: a book club, a library, a fire company, a philosophical society, a militia, a men’s social club, the Freemasons, the Royal Society of the Arts, the Lunar Society of Birmingham, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Whew. That’s a lot of monthly meetings.

14. Benventions

Among the newfangled stuff Ben’s inquiring mind cooked up:

Among the newfangled stuff Ben’s inquiring mind cooked up:

- Swim fins. A lifelong avid aquarian, Ben was only 11 when he increased his speed in the water by paddling while holding round wooden plates with holes for his thumbs.

- The armonica. Ben declared this musical instrument composed of dozens of color–coded glasses seated inside a cabinet his favorite of all his brainchildren.

- The urinary catheter. Inspired by the suffering of his brother, who had kidney stones and had to use a rigid metal tube to urinate, Ben in 1752 produced a flexible hinged version.

- The Franklin stove. Franklin’s initial version of this cast iron fireplace, intended to produce more heat, didn’t work very well, but his friend and fellow member of the American Philosophical Society, David Rittenhouse, improved it significantly.

- The lightning rod. This pointed metal rod affixed atop buildings directs lightning strikes harmlessly into the ground.

- Bifocals. Weary of switching between eyeglasses for reading and distance vision, Ben sliced the lenses from two pairs in half horizontally and fit them together.

Ben never applied for patents for any of his many inventions, believing that knowledge should be shared freely. Or, as he put it, “That we enjoy great Advantages from the Inventions of others, we should be glad of an Opportunity to serve others by any Invention of ours. … ”

15. Rotten Apples on the Franklin Family Tree

In February of 1730, Ben’s acknowledged illegitimate son, William Franklin, was born. The identity of his mother has never been discovered. William was raised by Ben’s common-law wife Deborah, and there has been speculation that she gave birth to him, but no one knows for sure. William grew up to be a lifelong Loyalist — a supporter of the British crown — much to his father’s chagrin. He served as the governor of New Jersey from 1763 to 1776, when he was arrested and imprisoned by Colonial troops. After the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781, William headed to London and never returned to the New World. Father and son met once more there, briefly, in 1784, to iron out some legal matters.

While studying law in London in the 1760s, William sired an illegitimate son of his own, William Temple Franklin, known by his middle name. Alas, like his father, he proved a disappointment to his grandfather, with whom he lived for a number of years. He sought but never was given a diplomatic post for the new nation, lived in London and Paris, had an illegitimate son and daughter, indulged in land speculation, and gained and lost a fortune before dying in 1823.

Ben’s only legitimate son, Francis “Franky,” died of smallpox at age four. Ben’s only surviving legitimate offspring, Sarah “Sally” Franklin, was born in 1743. She married Philly merchant Richard Bache in 1767 and had four sons and four daughters, all but one of whom survived infancy and produced assorted children.

Artwork courtesy Archives/Alamy Stock Photo

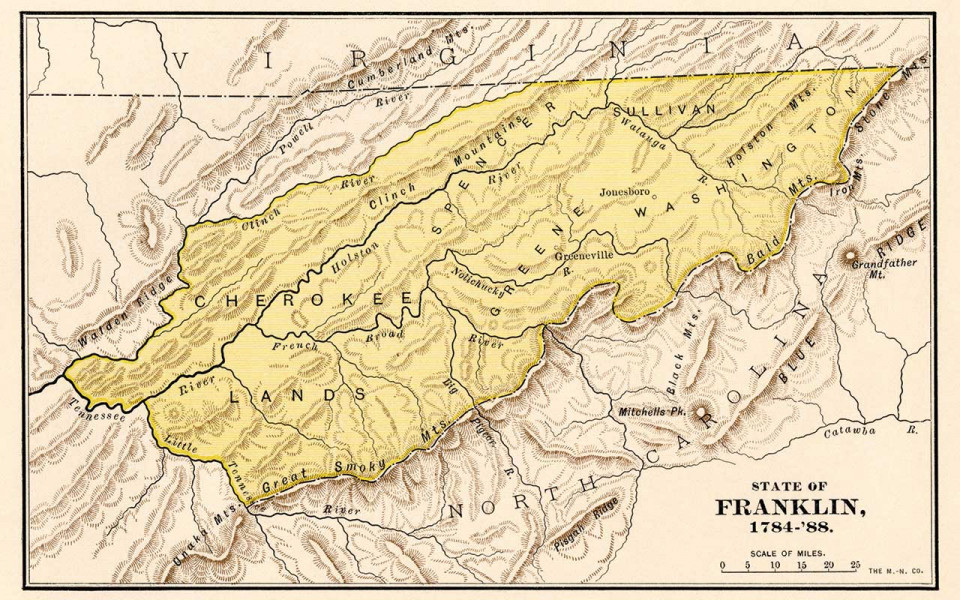

16. Ben Got His Own State … Briefly

What we know today as Tennessee was once part of North Carolina. In 1784, residents of the region were frustrated with the state’s government, so they seceded, forming their own State of Franklin. Regrettably, political divides and infighting led to the collapse of the State of Franklin in 1789, one year before Ben himself died.

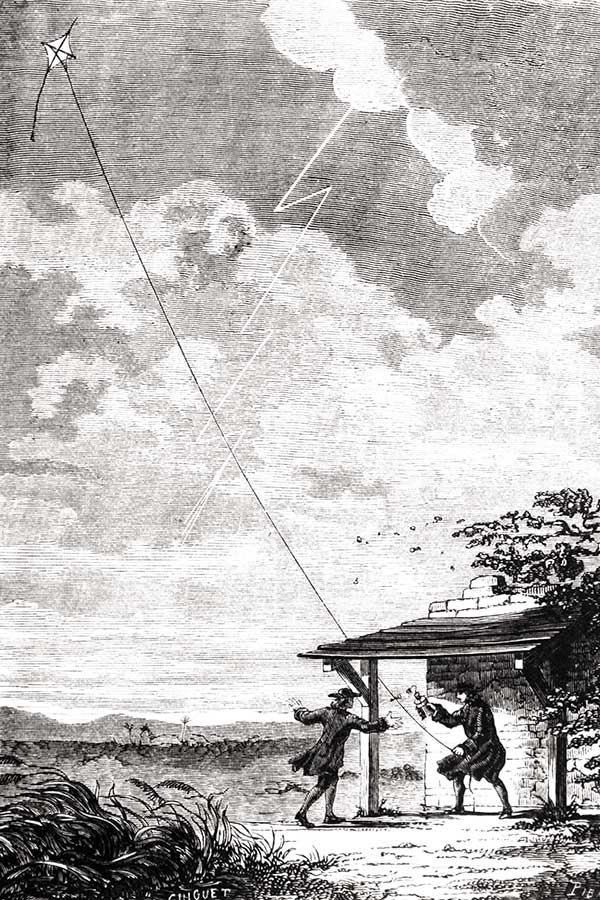

17. The Lowdown on That Electricity Thing

So Ben didn’t “invent” electricity; nature took care of that. And people did know about electricity; they used it for parlor tricks that employed sparks and shocks. What Ben did was observe that there are similarities between electricity and lightning, then prove they’re the same thing by flying that kite in a thunderstorm in 1752 with the help of his (grown) son, William. And the kite wasn’t struck by lightning, as that would have cooked Ben proper. Instead, it picked up an electrical charge from the atmosphere that was conducted through the kite string to an attached metal key. When Ben moved his knuckle near the key he got an electrical shock. The experience helped guide future experiments and inventions like the lightning rod.

Artwork courtesy Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

18. Ben’s Shocking Party Tricks

Ben enjoyed amusing guests with electrical tricks, and for a dinner party in the summer of 1749, he put on an electrical barbecue. He killed a turkey with an electrical shock, which he believed made the meat more tender, then roasted it in his fireplace on an electrified rotisserie. Guests drank wine from electrified glasses that delivered mild jolts. A similar production went awry when the deadly shock meant for the turkey got delivered to Ben instead. Guests saw a flash and heard a thunderous crack; Ben was knocked unconscious and was sore for days afterward.

19. The Man (Is) on the Moon

Ben is in good company with da Vinci and Copernicus (well, and Michael Jackson) on the list of people with craters on the moon named after them. The Franklin Crater is 35 miles across, and if you have a telescope in your closet, you can find it between Mare Crisium and Mare Tranquillitatis, just northwest of the landing site for the final Apollo moon mission.

20. Ben’s Better Alphabet

He wanted to fix English so it would be more logical. One can see the appeal. In 1768, he created an improved alphabet that Noah Webster (of dictionary fame) included a description of in his 1789 work Dissertations on the English Language. Ben’s version excised six letters — C, J, W, Q, X and Y — that he deemed confusing, doubled vowels (as in “ee” and “aa”) pronounced as long sounds, and added six new letters representing common sounds like “ng,” “sh” and “th.” He hoped his system would improve spelling — a new alphabet for a new nation! — and even had special printing blocks made for it. Alas it never caught on.

21. Ben + Penn

Did you know that the University of Pennsylvania’s shield is a mashup of Ben’s coat of arms and William Penn’s coat of arms?

22. Founding Fashionista

You may think Ben looks quaint in his cravat and breeches, but in his day, he was considered highly dashing. When he was sent to France to seek military help in fighting the Revolution, he affected a fur hat, thinking it fit the French image of Americans as primitive frontiersmen. The hat became his signature, and French ladies began wearing wigs approximating the look known as “coiffures à la Franklin.”

23. Ben the Breaststroker

No, we’re not talking about his reputation with the ladies. Though most of us picture the bloated man from his later years, in his prime Ben was arguably the Michael Phelps of his time, swimming in the Thames, Seine and Schuylkill rivers, sometimes in the buff. “The exercise of swimming is one of the most healthy and agreeable in the world,” he once wrote. True to this day. Well, assuming you’re not swimming in the Schuylkill, that is.

24. Ben Bet on the Wrong Bird

Can you believe that Franklin thought this weirdo, the turkey, was somehow superior to the majestic bald eagle, our national bird?

Artwork via Getty Images

Franklin felt eagles were of “bad moral character,” in part because they sometimes steal their food from other critters. A man of strong principles, indeed.

25. Ben the Corn Enthusiast

European newcomers to America wanted nothing to do with starchy old corn, which wasn’t a thing on their former continent. But Franklin was a huge fan of the veg. He became quite the corn booster, introducing diners to “parched corn” (popcorn’s predecessor) and grits, and those little kernels finally caught on. Today, the United States is the world’s largest corn producer.

26. The Fake News OG

Though that exact term only became fighting words in the 21st century, mischievous Ben published true masterworks of misinformation. Not only did he pen numerous stories that would give Factcheck.org’s analysts aneurysms. He took it a step further, publishing an entirely fake version of an actual newspaper, including in it a fake story about a fake incident during the Revolutionary War and even running a fake letter from John Paul Jones, a real war hero, to bolster his claims. Imagine if this Ben guy had a Facebook account!

27. From Slave Owner to Abolitionist

Like many of his peers, Ben owned slaves. Unlike many of his peers, he came to loathe slavery in his later years, emancipating those in his household. In 1787, he became president of the country’s first abolitionist group. He raised money to help free slaves. And just a few months before his death in 1790, in his last public act, he petitioned the 1st U.S. Congress to ban slavery in the newly formed nation — something that wouldn’t happen for another 75 years.

28. Ben in Pop Culture

Artwork courtesy Gene Colan/Marvel Entertainment

COMIC BOOKS

- As a companion to the superhero Deadpool, Ben turns himself into a ghost using the power of — what else? — electricity.

- Dr. Strange and his girlfriend Clea travel back in time and meet Ben, who promptly seduces buxom Clea with whiskey and apples.

- Though Ben didn’t appear in any of the Spider-Man comics, Spidey’s respectable uncle Ben Parker, who raised him, was named and modeled after Franklin.

VIDEO GAMES

- Assassin’s Creed 3: Ben’s womanizing side is played up, and gamers try to help him find missing pages of his almanac.

- Tony Hawk’s Underground 2: In the third mission of the skateboarding game, you complete a goal by chasing skateboarding Ben into a school building. (No, we don’t understand this stuff, either.)

- The Adventures of Benjamin Franklin: A retro arcade game created by the Franklin Institute. You play Ben and collect keys and lightning bolts while avoiding rats (so Philly!) and other obstacles.

TELEVISION

- The Flintstones, 1965: Fred travels through time and happens upon Ben in the middle of his kite-and-key experiment. Fred takes the kite string and promptly gets electrocuted. Ever the scientist, Ben takes notes.

- Bewitched, 1966: All of Samantha’s magic can’t seem to fix a lamp, so her goofy Aunt Clara steps in. “Wizards of AC/DC transmission,” she chants. “Send me … an electrician.” Franklin appears in a poof of smoke.

- The Office, 2007: Michael tells Jim to hire a male stripper for Phyllis’s bridal shower. Instead, he hires a Ben impersonator who knows so much about Franklin that Dwight thinks there’s a slight chance he might be real.

- Saturday Night Live, 1992: Ben (played by Phil Hartman) time-travels to 1992 to help solve the deficit problem, only to become frustrated with (ironically, considering Ben’s own penchant for propaganda) the sensationalist news media. Bonus: This was the infamous pope-photo-ripping Sinead O’Connor episode.

29. Ben and the Jersey Devil

The menacing, Pine Barrens-lurking Jersey Devil is, of course, the child of Mother Leeds, a woman who lived in the area with her family in the 1700s and whose unholy union with Satan himself spawned the winged beast. Or something like that. And how did this legend begin? Historians say the well-traveled rumor may have originated with Franklin, who was a staunch business and political adversary of the Leeds clan.

30. Chess, Anyone?

Ben played a mean, mean game of chess, a skill he honed in the cafes of gay Paree. As he wrote in his 1786 essay “The Morals of Chess,” the lessons the game offers were a path to a better existence, sort of like Dianetics. In 1885, the Franklin Chess Club — the second in the nation — was founded in his honor; it remained active until recently, when it shut down because membership dwindled. Too bad they couldn’t hold on for The Queen’s Gambit.

31. It Ain’t Easy Being a Franklin

There’s a wide network of Ben Franklin descendants in the country, and they occasionally get together for reunions, sometimes at Old City’s Christ Church, where Ben is buried. But don’t think that all of them go around advertising their connection to the big man. “When you have this kind of heritage, it’s somewhat of a burden, because you feel you should do something great with your life,” Franklin descendant Sarah Franklin Jayne told the Wall Street Journal in 2006. “And perhaps like anyone else you’re very normal.”

32. Ben in the White House

Donald Trump is said to be a big fan of Andrew Jackson, whose legacy has taken a nosedive in recent decades. When Trump became president, he had his decorator procure a portrait of the white-supremacist seventh president for the Oval Office. And what did Joe Biden do upon occupying that big desk? He kicked Jackson out of the Oval and moved a 1785 portrait of Ben by French painter Joseph-Siffred Duplessis to the same prominent position.

33. Ben’s Stony Gaze

The massive 30-ton statue of Ben inside the Franklin Institute’s rotunda isn’t just an impressive piece of artwork. It’s also, by declaration of the U.S. Congress, his official national memorial, like the Lincoln Memorial in D.C. Sculptor James Earle Fraser, who also designed the Buffalo Nickel, spent six years crafting the statue, from 1906 to 1911.

Photograph courtesy Hemis/Alamy Stock Photo

34. Did Ben Kill Beethoven?

Love a good conspiracy theory? Hold onto your tinfoil hat! Ben invented the glass armonica, a musical instrument that back in the day contained a fair amount of lead glass and lead-based paint that the player would be exposed to, since the whole idea is that you touch the glass with your moistened fingers. He introduced the possibly poisonous instrument to good old Ludwig van, who composed a song for it. Back in the 1990s, scientists studying Beethoven’s hair discovered — are you ready for this? — lots of lead, 100 times what should have been there, telling professional armonicists what they already suspected: Franklin’s armonica may have played a role in Beethoven’s death. According to one armonicist who spoke with the Los Angeles Times about the theory in 2001, the rumor had been “running around in the armonica community” for years. Most surprising about all this? That there is an armonica community.

35. An Ill-Begotten Bolt

If you’ve ever driven over the Ben Franklin Bridge from New Jersey into Philadelphia, you can’t miss the piece of twisted steel at the foot of the bridge that’s supposed to represent a kite, a lightning bolt and a key. The unfortunate tribute to Ben’s experiment was once called “the ugliest piece of art in Philadelphia” by this very magazine, and even after overpaying $850,000 for it back in 1984, the Port Authority wasn’t sure it would actually display it. Then one Port Authority official pointed out a silver lining: “It’s so damn ugly, it’ll take people’s minds off the higher tolls.” Thus the monument went up, and so did the tolls — by 25 percent.

36. About That Bridge

It would seem perfectly fitting that the builders of what was then the world’s largest single-span suspension bridge and the only one connecting Philly and Jersey would name said bridge after the city’s favorite father — especially since the bridge was dedicated in 1926, on the sesquicentennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Alas, it was boringly christened the Delaware River Bridge. Ben only earned the namesake nod when the much less impressive Walt Whitman Bridge was built in 1957.

37. Famous Things Ben Didn’t Say

According to the Franklin Institute (and who would know better?), Ben’s often credited for witticisms he, uh, isn’t responsible for. Among the best-known misattributions:

- “A penny saved is a penny earned.” Nah. Sorry. What he did write in Poor Richard’s Almanac: “A penny saved is two pence clear.” Not nearly as catchy.

- “God made beer because he loves us and wants us to be happy.” Ben wasn’t one to turn down a drink, mind you, but what he actually wrote this about was … wine.

- “Lighthouses are more useful than churches.” He almost certainly agreed with the sentiment, having once escaped a shipwreck, but nope.

- “Any fool can criticize, condemn, and complain … and most fools do.” That would be Dale Carnegie, we’re afraid.

38. President Franklin??

A 2016 study by memory researchers at Washington University at St. Louis showed that a quarter of Americans falsely believe Ben was president of the United States. Shocked? Don’t be. A full 71 percent of those surveyed said Alexander Hamilton was president once upon a time.

39. The Original Pro-Vaxxer

Smallpox was a scourge of the human race for many centuries, expanding as trade routes evolved. (Pustules have been found on ancient Egyptian mummies.) Vaccination against the viral disease, which killed three in 10 victims and disfigured many more, was introduced to the U.S. by an enslaved African, Onesimus, in the early 1700s. In the 1730s, Ben was a public proponent of smallpox vaccination efforts. When his four-year-old son Francis died of the disease in 1736, those who opposed vaccination started rumors that vaccination had caused his death. Ben published a notice in the Pennsylvania Gazette refuting the gossip: “I do hereby sincerely declare, that he was not inoculated, but receiv’d the Distemper in the common Way of Infection … I intended to have my Child inoculated.” Many years later, in his autobiography, he wrote: “I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation.”

40. Ben and Vegetarianism

Ben dabbled in vegetarianism throughout his lifetime on the grounds of philosophical objections … then finally began eating critters again because he couldn’t resist the smell of fried fish.

41. Ben Gone Wrong

Nobody loves the guy more than we do. But sometimes, love goes awry. Here, a few Franklin “tributes” we’d like to see die.

- The Impersonators. Guys. It’s not cute that you dress up in faux 18th-century clothes and walk around Old City desperately trying to interact with children and tourists. It’s creepy. Begone with ye!

- Ben Franklin, Craftsman. A.k.a. that hideously misshapen statue the Freemasons gave to the city that sits on the northeast skirt of City Hall. We’ve heard rumors sculptor Joseph Brown was going blind when he made this. We believe them.

- Daylight Savings Time. He proposed it as a joke, people. He was making fun of Parisians for being lazy slugabeds. He never, ever meant that every goddamn spring, we should yank ourselves out of bed an hour earlier and screw up everybody’s biological clocks just to save money on candles. Sheesh. Is humor dead?

42. Ben Franklin Slept Here

The building at 36 Craven Street in London where Ben stayed for nearly 16 years, near the Whitehall Gardens and Trafalgar Square, is the sole home he ever lived in that still stands today. It’s now Benjamin Franklin House Museum, opened in 2006. In 1998, during construction to conserve the building, workers uncovered a cache of some 1,200 human and animal bones in the basement. They’re believed to be remnants from an anatomy school run on the site in the 1770s, during Ben’s tenure, by William Hewson, the son-in-law of Ben’s landlady. Hewson made valuable contributions to knowledge of the lymphatic system.

![]() 43. Ben Delivers the Mail on Time

43. Ben Delivers the Mail on Time

As postmaster general for the City of Philadelphia and then for the Colonies, Ben greatly improved and expedited mail delivery. Under the British, the job didn’t pay much — just a 10 percent commission on customers’ postage — but its “franking” privilege let Ben mail his newspaper for free, which helped make the Pennsylvania Gazette a big hit. His improvements in scheduling and system analysis cut the time for a letter and its reply to travel to New York City and back to Philly to 24 hours, which — you know, we’d settle for that today. The spread of information and knowledge via the postal service greatly contributed to the success of the young American nation.

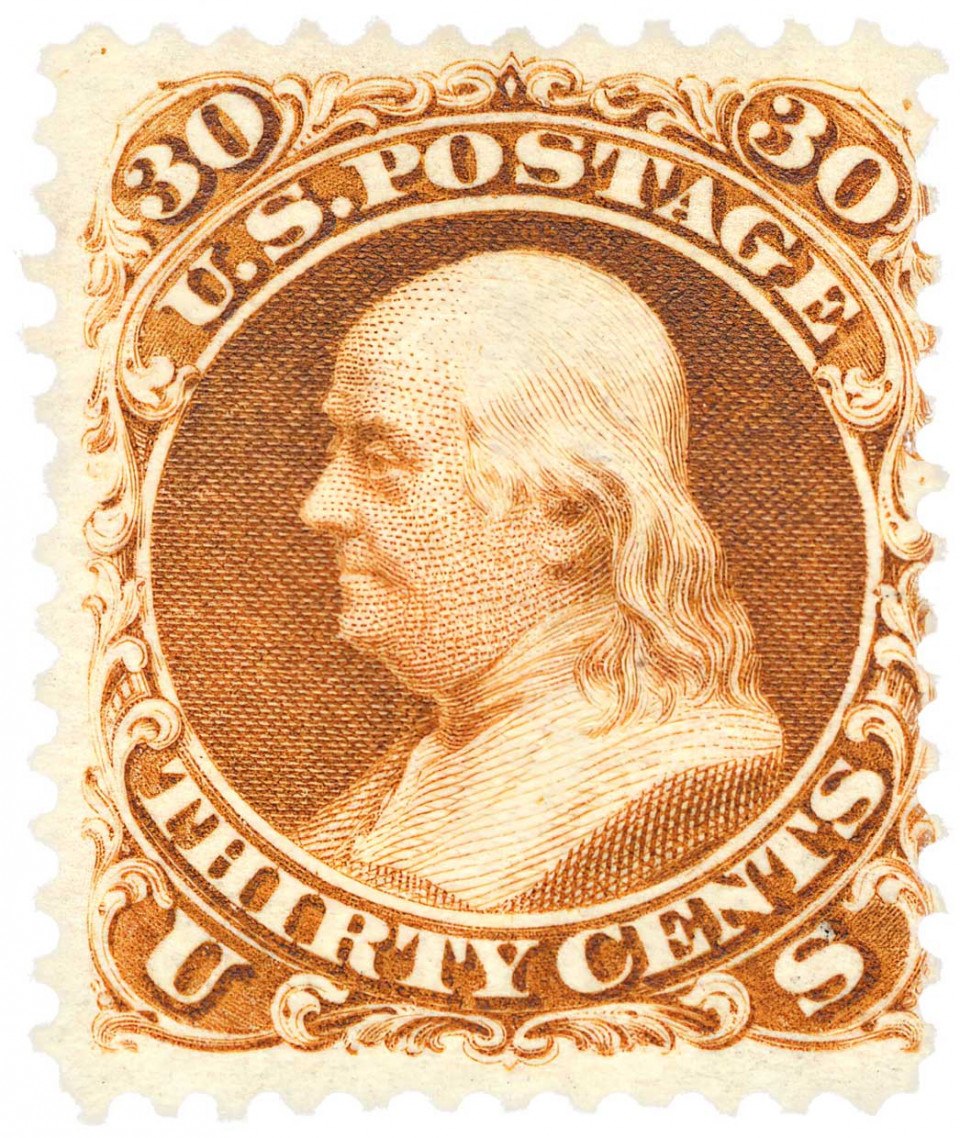

44. Ben Franklin: Coin Artist

The first circulating coin in the United States was designed by Ben and minted for only one year: 1787. The copper coin showed a sun shining down on a sundial and bore the motto “Mind your business,” a little double-meaning fun from its creator. Today, you’ll spend at least $1,000 if you want to own one—a mighty hefty markup.

45. Ben’s Epitaph

By the time Ben died, he’d long since written his epitaph, in 1728. It appears today on a plaque outside Christ Church:

The Body of B. Franklin, Printer;like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms.But the Work shall not be wholly lost;For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition,Corrected and amended By the Author.

Burns on Ben

Three questions for the legendary documentarian:

Photograph by Evan Barlow

- Why Ben?

I’m curious about how my country worked, and I love good stories. And among those stories of our founders, we are still woefully ignorant of Jefferson and Washington but even more so about those who didn’t make it to the presidency. Without Franklin, there is no United States. The last film I completed was Muhammad Ali. He was born on January 17th, as was Franklin. Ali was arguably the most compelling American personality of the 20th century, and Franklin of the 18th century. I’m not into astrology, but there you go. - What would Ben think of our society today, our politics, social media?

He was a social media pioneer, writing and publishing on a printing press, the most modern form of communication in its time. We aren’t in a special time now. We just have different ways of getting the information out. And his life intersected with themes going on right now: the ever-present question of race, political divisions, xenophobia, internationalism, science, vaccines, Indigenous people. - I’m sure you knew way more than the average person about Ben before embarking on this project. What truly surprised you?

I knew the extent of his genius and his interest in the common good. He’s the greatest diplomat in American history. We all know about the kite experiment, but you don’t know the depth of him as a scientist. He was Nobel-level. But the thing that was really surprising to me as somebody who thinks he knows a lot about race and enslavement: A lot of his work was possible only because of the people who didn’t get paid — his slaves, Peter, Jemima, Othello, George, John and King. Their names disappear in history. He did become an abolitionist late in life, but let’s remember that his comfortable life was only made possible by these other people.

Published as “All About the Benjamin” in the April 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

10. The Room Where it Didn’t Happen

10. The Room Where it Didn’t Happen 43. Ben Delivers the Mail on Time

43. Ben Delivers the Mail on Time