Expect a Rise in COVID Cases for the Next Month, CHOP Says

The latest CHOP COVID projections for Philly suggest a challenging fall ahead. Photo Kevin Dietsch/Getty

The Policy Lab at CHOP has been a leading voice when it comes to trying to model the course of the pandemic. It’s the kind of job where all you really want is to be put out of business. In May, that finally happened: Cases were so low across the country that there wasn’t much to model anymore.

That was then; this is now. Thanks to the emergence of the Delta variant, along with rising cases and hospitalizations in parts of the South — states like Mississippi, Texas, Florida and Louisiana have been those especially hard hit — CHOP is bringing back the model. The forecast, which looks at a host of factors including current cases, population, regional movement trends and county-level vaccination rates, ultimately tries to discern where things might be in four weeks’ time. If you’re a parent, you know that’s right around the time schools are reopening. We checked in with CHOP modeling expert David Rubin to find out what the model holds for Philadelphia and the region.

Current Projections in the Philly Region

As it stands, Philadelphia is seeing its highest weekly case counts since May; the current figures also top the number of cases at this time last year. But there is one sign of good news: The number of hospitalizations, while rising, is at an average of 139 over the past two weeks, below the most recent peak of 520 in April. Sixty-four percent of Philly residents are fully vaccinated, and despite the high number of hospitalizations in some states, the vaccines, by some estimates, remain between 85 to 95 percent effective at preventing severe illness, even against the Delta variant.

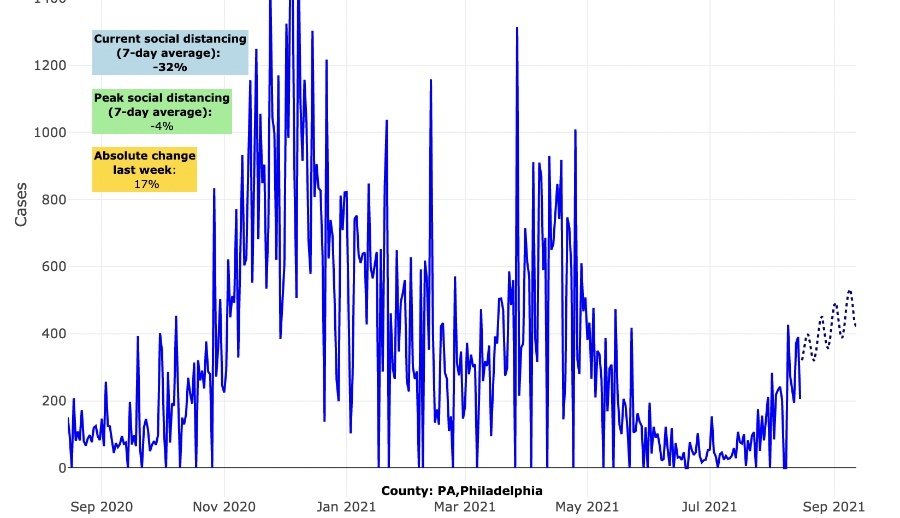

Rubin’s model suggests that cases will continue to rise in Philly over the next four weeks. The “reproduction number,” which is to say the number of additional infections resulting from each COVID case, is actually modeled to drop from its current level of 1.7 to about one by September 11th. But in order for cases to start declining, that figure needs to drop below one; otherwise, each new case will just create another additional case, effectively establishing a plateau. That’s why the model projects cases in Philly to rise from the current two-week daily average of 268 cases over the next four weeks.

Current COVID projections for Philadelphia, according to the CHOP model. The projected rise in cases is noted by the dotted line.

The most critical question is how that predicted rise in cases will affect hospitalizations. Even if 79 percent of Philly residents have received at least one dose of vaccine, we can learn something from cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco, which have similarly high vaccination rates yet are still experiencing bumps in hospitalization of their own.

“It’s a real tenuous time here,” Rubin says of the Philly region. “There’s a fair amount of uncertainty.”

Seasonality and Regionality

In the spring of 2020, scientists held out hope that the coronavirus would follow the seasonal patterns of many other respiratory illnesses and cease to spread as much during the warmer summer months, particularly as more people gathered outside. Of course, that didn’t happen — at least, not everywhere. While Philly’s cases during the summer dropped below the spring peak, parts of the South and Midwest spiked. This, Rubin explains, is one of the important factors to remember about the virus: Yes, it’s seasonal, but it’s also regional. Right now, we’re seeing spikes yet again, and in some cases record levels of hospitalizations in states like Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi.

“Last summer, there was a similar pattern of early resurgence,” Rubin says. “Now everything is speeded up a little bit because we’re largely unmasked and going to large gatherings.” Not to mention the fact that the Delta variant is both more transmissible and believed to be more virulent than earlier strains.

At the same time, transmission is increasing in the Upper Midwest as well as parts of upstate New York. Rubin predicts that some of the spikes in the South will slow down in the coming weeks, as there are fewer and fewer new people for the virus to infect. But that may not be the case here in Philadelphia, which has been spared from recent waves.

Adding to the difficulty of modeling right now: While historically, the early fall has been a time of lower rates of transmission — with people returning from summer travel and gatherings and spending more time at home — this season figures to have large gatherings like football games, not to mention the return of in-person schooling. Those forces could act as an accelerant. Of course, on the other hand, there’s now vaccination acting as a brake.

Still, for now, the model predicts growth, which Rubin thinks may in fact have something to do with the Northeast’s past resilience. Unlike other parts of the country, Rubin says, “We probably have a lot more room to grow than people expect.”

Despite Surge, Parents Shouldn’t Be Overly Worried

This latest wave of cases has produced lots of concern over the increasing numbers of infections among children. Could it be that the Delta variant is more infectious among kids? Rubin isn’t so sure.

“I don’t think the data is persuasive that the risk of hospitalization has changed,” he says, noting that across the entire Northeast right now, there are only about 50 kids hospitalized with the virus. Even in Florida and Texas, there are just 400 total kids in the hospital. That number is way too high, to be sure, but at the same time, there are more than 11 million children in those two states. “The last thing we need to do is terrify families at the onset of school,” Rubin says.

Instead of one-size-fits-all policies, Rubin laid out in a recent blog post a series of à la carte options depending on the situation on the ground. Masking during periods of pronounced spikes would be prudent. But it might be possible in other areas to only require masks, say, when kids are at the cafeteria, in the hallway, or on the school bus. The fundamental tools for all schools, though, Rubin says, should be consistent quarantine and contract tracing protocols. Even better if there’s weekly testing. And, obviously, more vaccinations mean fewer people who are susceptible to the virus and serious disease.

The Metric to Watch: Hospitalizations

As with kids, it’s important not to get overly preoccupied with rising cases. “The messaging around vaccines gave people the idea this was some kind of impenetrable shield,” Rubin says. “We don’t look at vaccination that way. What we’re hoping is to reduce the risk for severe disease.” By and large, that does seem to be working — even with presence of the Delta variant. In California, for instance, a New York Times analysis recently found that there were just 1,615 people hospitalized with breakthrough infections — about .007 percent of the 22 million fully vaccinated people in that state.

So while cases may rise here in Philadelphia, that doesn’t mean the vaccines aren’t working. The question of how well the city performs in preventing a surge in cases will really be graded based on how many people end up hospitalized.

The lesson from the regions currently surging is that even if upwards of 70 to 80 percent of your elderly population is vaccinated — as is the case in vaccine-hesitant states like Mississippi — that still leaves plenty of susceptible and vulnerable people open to severe infection. “Lots of folks ran out of time and didn’t have that opportunity” to get vaccinated before the recent Delta surge, Rubin says. There’s still time in the Philly region.

“But,” he adds, “that window is closing.”