How a Pop-Up Clinic Is Working to Close Philly’s Vaccine Equity Gap

Here’s how Penn Medicine, Trinity Health, and community faith leaders collaborated on “operationalizing equity” around COVID-19 vaccine distribution.

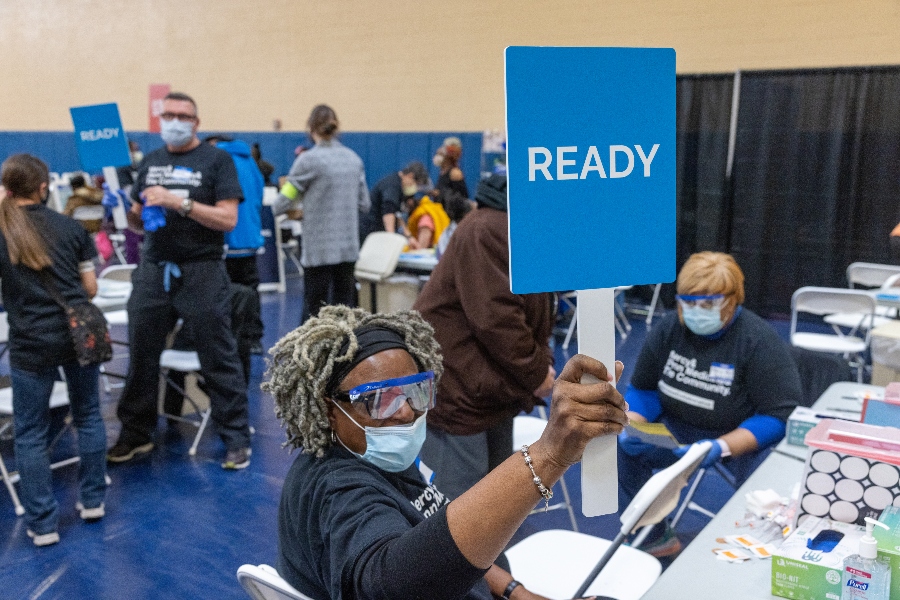

Since mid-February, a health system and community leader collaborative has been working to improve vaccination disparities in Philly. Photograph courtesy Penn Medicine

Nearly four months since the first COVID-19 vaccine was administered in Philadelphia, health commissioner Thomas Farley announced on Tuesday that the city administered its one millionth dose. Though a milestone, the city still has a long way to go — only 22 percent of Philadelphia’s total population is fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

More urgent, though, is the ongoing racial, economic, and geographic disparities that exist regarding vaccine sign-up and distribution. The city has attempted to close the vaccine equity gap by allowing walk-up appointments at the Center City FEMA site, operating health department clinics in traditionally underserved neighborhoods, and opening a second FEMA location in Hunting Park focused on reaching the Hispanic community. And since February, Ala Stanford’s Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium has been administering vaccines for residents of the Philadelphia zip codes with the highest incidence of COVID-19 disease and death.

The disparities in vaccination in Philadelphia have also inspired a collaboration between Penn Medicine, Mercy Catholic Medical Center-Mercy Philadelphia Campus, and community faith leaders, who worked together to launch a rotating vaccine clinic. Since mid-February, the partnership has run seven clinics out of churches, recreation centers, and school gymnasiums in West, Southwest, and South Philadelphia. In their first three clinics, they vaccinated 2,821 people, 85 percent of whom were Black.

On April 7th, the organizers behind the clinic detailed their methods in NEJM’s Innovations in Care Delivery journal, in an article titled “Operationalizing Equity: A Rapid-Cycle Innovation Approach to Covid-19 Vaccination in Black Neighborhoods.” In it, the authors describe how the unique partnership between two health systems and community leaders worked to combat the structural barriers preventing communities of color from accessing vaccinations.

To learn more about their efforts, triumphs, and challenges, we spoke with Kathleen Lee, director of clinical implementation at Penn Medicine’s Center for Health Care Innovation and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Penn, who helped design the clinic model.

NextHealth: Why did this rotating vaccination clinic get started?

Lee: The genesis of the clinic stemmed from ongoing conversations our C-suite was having throughout the pandemic about the racial inequities related to COVID-19. Though, it’s important to note that this was a huge coordinated effort between us at Penn Medicine, Trinity Health, and faith leaders throughout the city, including Terrilynn Donnell, [pastor] W. L. Herndon, and [reverend] William Shaw. When it came to the topic of vaccines, we knew that one of the major driving factors of disparity is the structural barriers that limit vaccine access to underserved communities, specifically Black and Brown communities. Around January, we took an intimate look at those barriers as they emerge across Philadelphia in order to determine how to best create an incredibly inclusive environment for getting vaccinated. Around the same time, conversations started taking place between the health systems and community leaders to cultivate relationships and to leverage community networks and healthcare partnerships.

What did the collaborative identify as major barriers to vaccine access, and what were your solutions?

We found that geography and technology were preventing ease of access, so we brainstormed ways to create rapid-cycle solutions for a wide-spread implementation effort. We decided vaccine administration needed to be done in communities themselves, instead of making patients travel to a healthcare setting. Also, we built an SMS-based and an interactive-voice recording system for folks to schedule vaccine appointments. Overall, our objective was to have multiple, low-tech intake strategies with every step coordinated with and for the community to ensure that equity was at the core of every aspect of the endeavor. In a matter of months, we had created the #VaccineCollaborative, a novel multi-health system, community-partnered COVID-19 vaccination clinic.

What have you found to be some of the clinic’s biggest accomplishments?

Seeing the uptake work with the scheduling paradigm we created was truly delightful. Our first clinic location filled so quickly, and it was great to know that people were able to schedule their appointment in a way that is easier to use. Similarly, many folks had signed up a loved one who wasn’t able to do it themselves. That digital nudge drove home how communal and community-driven our effort was. But the uptake was reflected in more than just the scheduling system. In our feedback surveys, we had people write, “It was like you were glad to see me” (we were!) and “Thank you for having clinicians who look like me.” That kind of feedback is invaluable.

Another major accomplishment was the streamlined process we designed. As I said earlier, we strove to accommodate all types of sign-up strategies, rather than relying on one technique. It allowed us to honor walk-ins, which we know is very important to many people, especially those who need a no-technology method. We also made sure to create a no/low-wait experience by conducting a group-based consent process and having our vaccinators use “Ready” signs. That way, patients were shuttled through — not in a rushed way, though — so that they didn’t have to deal with long lines. This was especially helpful when it was extremely cold outside. Nobody deserves to wait in the cold!

Those providing the vaccines used “Ready” signs to keep patients moving through the clinic and reduce wait times. Photograph courtesy Penn Medicine

What challenges did the collaborative face along the way?

Setting up a novel clinic in a non-healthcare environment is a big task to take on. We leveraged resources from the healthcare systems to bring all the necessary supplies on site, including vaccine refrigerators, monitoring equipment, medical supplies, wheelchairs, and other items. Seeing a nimble operation happen outside of a hospital setting was amazing. We did run into some infrastructure challenges at the beginning, which we anticipated might happen. For example, at the recreation center, we discovered there weren’t enough accessible entrances for patients with limited mobility. In response, our health system employees tapped into their networks and got a custom ramp donated.

Another hurdle arose when more people outside of our targeted group became interested in getting vaccinated at our clinics. From the beginning, we’ve been very transparent and intentional with our mission in order to promote equity for local residents. That’s why we added a preliminary step on all our engagement platforms that required active acknowledgment of our mission statement prior to signing up. (It reads: IMPORTANT: The purpose of this clinic is to address the vast racial inequity in COVID outcomes and vaccine distribution by vaccinating our West & Southwest Philly *Black and Brown* communities hit hard by COVID. Here are the zip codes this clinic is designed to serve: 19104, 19131, 19139, 19142, 19143, 19151, 19153.) Though we didn’t turn anyone away or validate based on race or Philadelphia zip code, we found that about 36 percent of individuals who started the text process didn’t follow through with signing up after reading the mission disclosure.

How might this model be applied to other communities outside of Philadelphia?

Our model was designed for generalized ability and scalability, but putting it into action does require intentional and coordinated effort, resourcing, and leadership. And in order to promote vaccine equity, diversity and inclusion need to be at the forefront every step of the way. I think our article says it best in terms of steps to take: “Engage community leaders early to inform design, activate their networks, and build bridges of trust between health systems and the community around vaccination. Embrace no/low-tech platforms to support vaccine ambassadorship and distribution. Reimagine clinic flows to enable an on-time model with minimal to no wait to ensure an uncompromising patient experience.” Though partnerships have to be done at every level, I do think leaders in the healthcare system should be role models and take initiative in order to truly help and improve the lives of community members. If not us, then who?

Where do you see this rotating clinic going from here?

We plan to be intentional about this long-term and hope to extend the pilot for months to come. We already submitted an RFP to city officials, which has been approved.

Philadelphia magazine is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and economic mobility in the city. Read all our reporting here.