An Oral History of the Sound of Philadelphia

Fifty years after founding their legendary Philadelphia International Records, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, with friends and collaborators from Thom Bell to John Oates to Patti LaBelle, look back on the musical partnership that came to define the city.

Leon Huff (left) and Kenny Gamble in 1970, in the early days of their legendary partnership. Photograph by Charlie Gillett Collection/Redferns/Getty Images

In 1971, a lyrically gifted singer-songwriter from South Philly and a classically trained pianist from Camden launched Philadelphia International Records (PIR), a Black-owned hitmaking label that would write for and produce world-famous acts including the O’Jays, Teddy Pendergrass and the Jacksons.

No matter where you were in the country, you couldn’t avoid their songs in the 1970s — love ballads such as “Me and Mrs. Jones” and “If You Don’t Know Me By Now,” or dance hits like “Back Stabbers” or “TSOP” (a.k.a. the Soul Train theme song). The music, dubbed the Sound of Philadelphia, was played by an intensely talented pool of session musicians and orchestra players known as MFSB, which stood for “Mother Father Sister Brother.” But it wasn’t just about a sound. There was also an unmistakable feeling. This music and the message captured Philadelphia so perfectly that the songs resonate today just as much as they did back then.

Here, 50 years after the formation of PIR, and with a series of boxed sets and reissues on the way, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, with friends and collaborators from Thom Bell to John Oates to Patti LaBelle, look back on the legendary sound.

The Early Years

Kenny Gamble, co-founder, Philadelphia International Records: I grew up at 15th and Christian. I wasn’t raised in a musical house. I was self-taught. Didn’t have any kind of training at all.

Leon Huff, co-founder, Philadelphia International Records: Let me put it this way — when my mother conceived me in Camden, New Jersey, there was an upright piano waiting for me in the living room. My mother played for church, and I gravitated to the piano at a very young age. I learned to play it by ear.

Thom Bell, arranger, Philadelphia International Records; producer of the Spinners, the Stylistics and the Delfonics: My mother made me learn piano. And I was brought up very classically oriented, from the harp to the French horn. I knew about it all.

Leon Huff: My mom did have me take some formal lessons to learn the basics. But my ear was very powerful. My piano teacher told my mom the lessons were a waste of money. And I was playing the piano really good by age 10 anyway.

Kenny Gamble: It would have been great if they had music in the schools. You really do need music in schools. Oh, they had something like a music class when I went to West Philly High. But they didn’t actually teach you music. They didn’t teach you how to play an instrument. They didn’t teach you how to understand the science of music. We never had anything like that at all, and Huff and I talk all the time about how it would have been great if I could have learned to write symphonies. But I surrounded myself with people who were extremely talented with the music and the arranging.

Leon Huff: When I was in high school in Camden, they had a wonderful music program. I took drum lessons and made the all-star orchestra every year. I became very aware of what orchestrations sound like.

Thom Bell: I don’t even think I heard any rock-and-roll or R&B until I was 14. But then when I did, the arrangements really struck me, and I realized I wanted to be a part of that. I made a deal with my mom that if I got good on the piano, she would buy me a set of drums. And then one Christmas, my mother and father got me that set of drums, and I was as happy as a termite in a lumberyard. [laughs] And then I didn’t want to listen to Beethoven and Bach. I thought Mom Bell was gonna kill me when I told her I was tired of Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp minor.

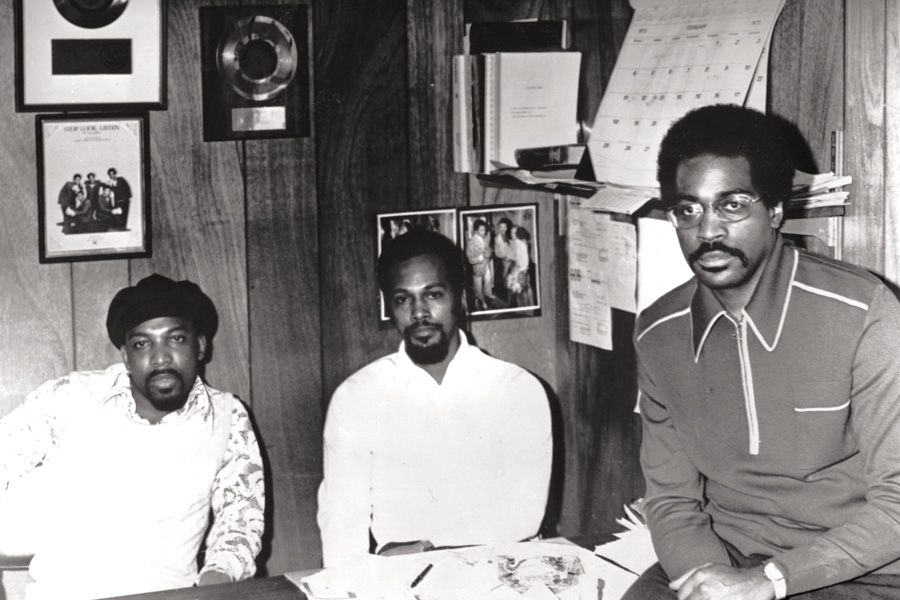

Huff, Thom Bell and Gamble in 1973. Photograph by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

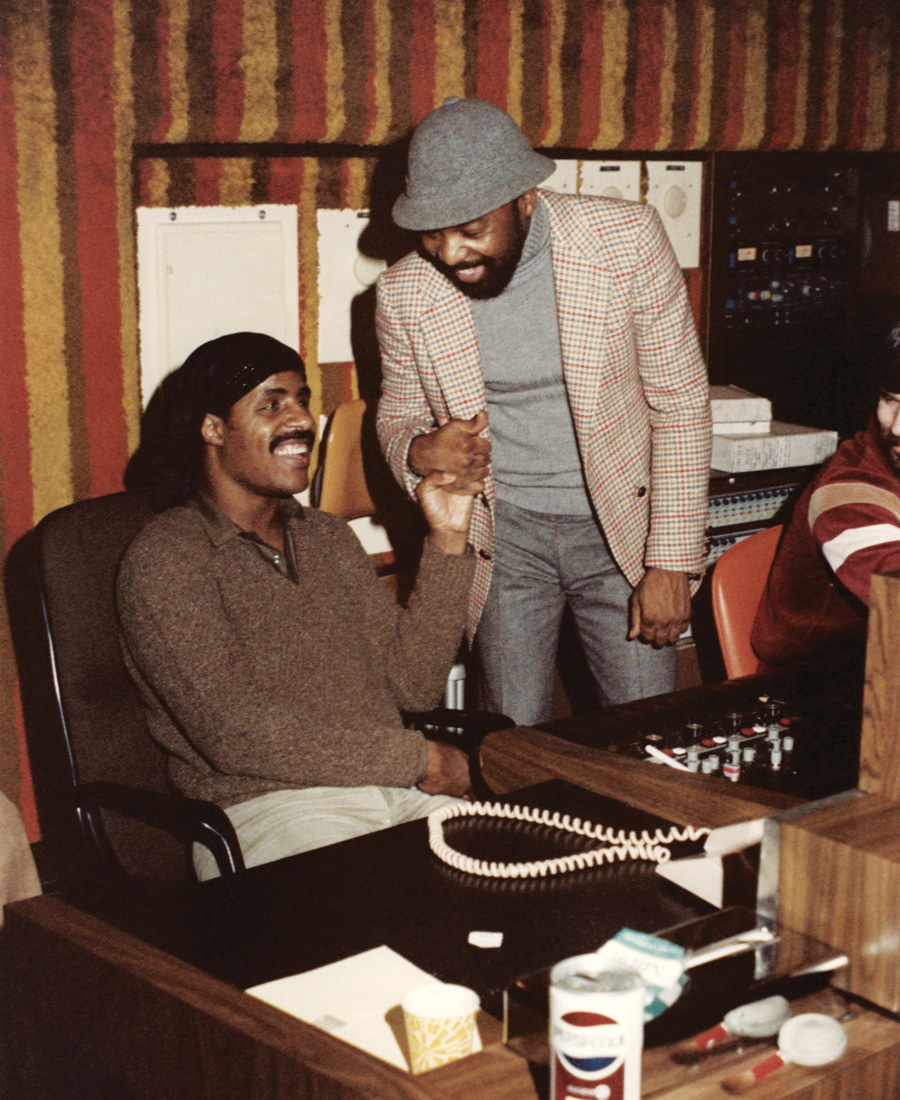

Stevie Wonder (seated) with Huff in 1980. Photograph by Echoes/Redferns/Getty Images

Kenny Gamble: In my neighborhood, we had so many corner groups that stood outside singing those doo-wop songs. I wound up singing with some of those groups with my brother and my cousin. And I wrote songs for those groups, too.

Patti LaBelle, singer; released three albums with PIR, including 1981’s The Spirit’s In It, which includes her masterful interpretation of “Over the Rainbow”: I first met Kenny, I think, when I was 15 or 16. I’m bad with dates. But he had friends on my block at 58th and Washington. He was always visiting them. They knew I could sing and they knew he was writing songs, so they told him he should meet me. So he comes and sits on the stoop at my mom’s house one day. I remember I wanted some beer, and I told him to tell my mom it was his beer if she saw me. [laughs] I sang for him, and he said, “Girl, you have to do something with that voice!” It wasn’t until some years later that we actually got a chance to work together.

Thom Bell: Gamble went to school with my sister. He knew I played. And he said, “Hey, man, I write songs. You play. We should get together sometime.” The next day, he and I were writing and singing. We had a blast.

Kenny Gamble: After high school at West Philly High, I went to school to become a lab technician. And then I worked in a lab with different cancer technologies. After work each day, I would go home and write songs and sing. And I formed a group called Kenny and the Romeos, with Thom on the keys. And that’s what really got the juices going. I was the only guy in the band who didn’t play an instrument. I was the up-front person. We were very busy. We used to take songs that were already hits and rearrange them. We would put together medleys of songs by Marvin Gaye, Junior Walker, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. Whatever was hot, really. That’s what we’d play.

Leon Huff: I became a session pianist in New York, living in Camden. I used to take the Trailways bus up and back two or three times each week. This was before I worked with Gamble. I played for the Quincy Jones sessions in New York City. And I played for Phil Spector and his group the Ronettes, who had a “little” hit called “Be My Baby.” [laughs] I was in New York, playing for some great producers and songwriters. I was nervous as hell, but I knew I had to shine, because it was a great opportunity. But then a lot of that session business moved out West. Quincy called me and said, “Come out to L.A.!” But I didn’t want to go out to California. So I started hanging around in Philadelphia, looking for sessions.

Kenny Gamble: I had been doing songwriting for a guy by the name of Jerry Ross, who had this company, Ross Associates, on the sixth floor of the Shubert Building on Broad Street. I learned a lot from Jerry. See, I knew how to put words together with a melody, but I didn’t know how to structure songs. And I didn’t know anything about the music industry. Jerry taught me all that.

Leon Huff: I had a job as a $50-a-week staff songwriter for a company on the second floor of the Shubert Building. The first time I laid eyes on Gamble was in the elevator there. I think he was carrying a guitar. We got to talking. He said he was a songwriter, and we both realized we were doing the same thing. And he said we should work together one day. And, well, as you know, that’s what happened.

John Jackson, music historian and author, A House on Fire: The Rise and Fall of Philadelphia Soul (Oxford University Press, 2004): The Shubert Building was one of a few places at the time that just happened to be songwriting hubs in Philadelphia. You had all kinds of songs being written out of that place.

Jerry Blavat, Philly DJ: In the early part of the ’60s, the big Philly labels were Chancellor Records, which had Frankie Avalon, and then Cameo-Parkway, which had Dee Dee Sharp, Chubby Checker and Bobby Rydell. And then you had these little labels, and Gamble and Huff both worked separately for the little labels before they got together.

Kenny Gamble: There was this place in Lawnside called Loretta’s Hi-Hat. And I was playing there every weekend with the Romeos. That spot was jumpin’!

Leon Huff: I saw Gamble with the Romeos at Loretta’s after I was done work one day at my other job at Cooper Hospital. I was washing dishes at Cooper. I got down to Loretta’s, and I couldn’t believe it. The line was around the corner. And these guys didn’t even have a record out. They were just great entertainers. And I knew I had to be a part of that band and work with him. But Tommy Bell was already the keyboard player, so I had to wait my turn. Then Bell got a job writing for Cameo-Parkway Records, and I took his place in the band. By the grace of the Almighty, the opportunity presented itself, and I just stepped right into that role.

Kenny Gamble: Jerry Ross had this group the Dreamlovers, and they had a song called “When We Get Married” that was a big record. So Jerry started to do pretty good for himself and got a big job in New York. I took over his office, and I called Huff on the second floor and told him to come work upstairs.

A Partnership Is Born

Leon Huff: We started hanging out and talking. And one day, he came over to my house in Camden. I was living in the projects, but I did have a piano. In one day, we must have written five or six songs. It was just spontaneous. And we knew we had to do this again. We knew we had to keep doing it. So we kept doing it. And we struck a groove.

John Oates, co-founder, Hall & Oates: Daryl and I were doing some songwriting work on the fourth floor of the Shubert Building while Gamble and Huff were up on six. Daryl also worked with Thom Bell, so we all knew each other pretty well. Daryl and I started solidifying things, and we had to make a decision. We could’ve gone up to the sixth floor to work sessions with Gamble and Huff. Or we could strike out on our own. This was just as Gamble and Huff were beginning to hit their stride. Then we got a record contract with Atlantic in 1971 and left for New York, which is where we did our recording. And then Gamble and Huff really took off.

John Jackson: Gamble and Huff already had major songwriting hits with “Expressway to Your Heart” by the Soul Survivors in 1968 and “Cowboys to Girls” by the Intruders in 1969. And with that momentum, in 1971, they solidified their partnership as PIR, which was backed by Clive Davis at CBS Records, a.k.a. Columbia. And they also formed, along with Thom Bell, Mighty Three Music, which was a publishing company. They started recording up at Sigma Sound, which had become really hot in the late ’60s.

Kenny Gamble: Sigma Sound had really gelled under Joe Tarsia. We knew Joe from his previous work with Cameo-Parkway Records. And so we took our business to him at Sigma for the recordings. We knew the quality of Joe and his team.

Max Ochester, owner, Brewerytown Beats record shop; music archivist; unofficial Philly music historian: Joe Tarsia had left Cameo-Parkway and took out a second mortgage on his home to purchase the second floor of a building on North 12th Street, calling it Sigma Sound. Joe was doing things with sound engineering that nobody else around was doing.

Kenny Gamble: Our strength was writing songs, finding artists, and producing records. We made the deal with Clive and CBS so that CBS would become our worldwide distributor and could concentrate on marketing and distribution, because that’s what they were good at. This made it much easier for us to concentrate on the music. We had Billy Paul, we had the O’Jays, we had Dee Dee Sharp in those days.

William Powell, Eddie Levert and Walter Williams (from left) of the O’Jays in the mid-’70s. Photograph by Don Hunstein/Sony Music Archives

MFSB performs at Sigma Sound in 1978. Photograph by Michael Putland/Getty Images

Leon Huff: Listen. I knew I could play piano. And I could write a song. And I could produce a record. But Gamble — Gamble could just spit out words spontaneously. He was a poet. I would throw in a word every now and then. But really, I was focused solely on the music, and Gamble was the lyric writer, the storyteller.

John Jackson: Kenny is shrewd. Kenny is a businessman. Kenny knows the angles.

Kenny Gamble: We started to develop a style. And we started tracking down more musicians. We had MFSB. We had an orchestra. An actual orchestra! That was important. And we began fluently writing songs every day.

Jerry Blavat: Gamble and Huff took things a step higher with Philly International. There were bigger orchestrations. Beautiful strings. Great musicians. And great writers. And with songs like “Wake Up Everybody” and “Me and Mrs. Jones,” they were telling these great stories with these big orchestrations. It was no longer all about what rock-and-roll or Motown did or what Cameo-Parkway did. This was its own thing. This was the beginning.

Patti LaBelle: This was totally different from Motown. You’re in the car. You turn the radio on. I would be listening to the radio in the car on my way to the airport to fly to a gig, and there would be a Motown song on. But then the song would switch, and I would know instantly that it was from Philadelphia. Philly and the Sound of Philadelphia just have a different kind of crispness. I can’t explain it. There was this grit, but it was also very heartfelt.

Leon Huff: We started using the same elements on every album. The same musicians. The same studios. And with all that and Joe Tarsia as the engineer, we actually developed a style that DJs began to recognize. It sounded like a Philly record. There was a style of writing. A style of recording. And we quickly developed a sound that became internationally known.

“The Sound of Philadelphia was totally different from Motown. You’re in the car, and there would be a Motown song on. But then the song would switch, and you would know instantly that it was from Philadelphia. It had a different kind of crispness.”

Max Ochester: There was a real friendship and idea and thought of We’re all in this together. It was truly for the love of the music and the people around it. It hit the heartstrings of the public. One of the things that made it special, in my opinion, was that Sigma Sound was a place for all races and cultures. It didn’t matter who you were. Everybody there and everybody with Gamble and Huff had the idea that the message needed to be love and uplift. Their partnership and relationship was the seed of all that.

Thom Bell: I really didn’t want to be enclosed or tied down. Huff wanted to be with the musicians all the time and do the writing. Gamble was brilliant as the businessman, and he could also write. And I took care of the arranging.

Making It Big

John Jackson: About a year into the deal with Columbia, Gamble realized it wasn’t having any success in marketing the records. Columbia was just out of their league when it came to R&B. Not many people know this, but Gamble went to them and told them they didn’t know how to market this music, and he worked out a new setup where he said: You give us the money you wasted on promotion, and we’ll spend it well. Columbia realized they had nothing to lose, so they did it. Kenny was streetwise and knew where to put the money, if you know what I mean. But if you couldn’t get a DJ to play a record, you might as well not have a record.

Kenny Gamble: Motown was the inspiration for what I did. There, you had a group of people from Detroit who were able to put together a system where they had songwriters and young musicians all together, and they had a publishing business. And that taught young guys like me that it’s possible to participate in the business aspect. Not just dancing onstage and everything. You can own the songs. And that took my interest very much.

Patti LaBelle: Leon was such a quiet, quiet person. And you didn’t think he was going to do anything. But then he would sit down at that piano and I would say, “Thank you, Jesus.” They really had that Philly laid-back thing going on when he got on that piano.

Bobbi I. Booker, Philly journalist and DJ: Mr. Huff will strike you as the quiet one. That’s how he always struck me. But don’t sleep on him, because his music skills are no joke. He’s just a phenomenal keyboardist. Occasionally these days he’ll do a Facebook Live session from his studio, and the man can still get down!

Kenny Gamble: We were producing a lot of albums. You gotta put in the time to do the songwriting, and it could take up to a year just to write the songs. And then you have to actually produce them. With Lou Rawls, all you had to do was give Lou a great song and it would come out great every time. These days, it might be five years before you make another album.

Bobbi I. Booker: Lou Rawls was huge for Philly International. He did several albums with Gamble and Huff. He just became a huge part of the Philadelphia sound. And he wasn’t from Philadelphia, but he became a Philadelphian anyway. He would show up. He would get his hair cut at Process Junior’s on South Street. He poked his head into Bob and Barbara’s a couple of times.

Kenny Gamble: Cameo-Parkway was once the number one recording company in America. They had Chubby Checker and Bobby Rydell. After they shut down, we left the Shubert Building and moved into their space at 309 South Broad Street. It was all set up because it was Cameo-Parkway, and all we had to do was remodel a little bit.

Thom Bell: What people call the Sound of Philadelphia, I had a hand in almost all of those songs. The O’Jays’ “Back Stabbers.” Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me By Now.” You name it. We were happy. We were from Philadelphia. We were eating Tastykakes and hoagies and drinking Frank’s sodas and making music. We talked the same. We sounded the same.

Max Ochester: I’m 43, so I didn’t exactly grow up with this music. I actually grew up listening to hip-hop. And I became familiar with a lot of the Philly International stuff through these hip-hop groups sampling the ’70s stuff, the stuff from Gamble and Huff. And later, I decided to take a deep dive into their music.

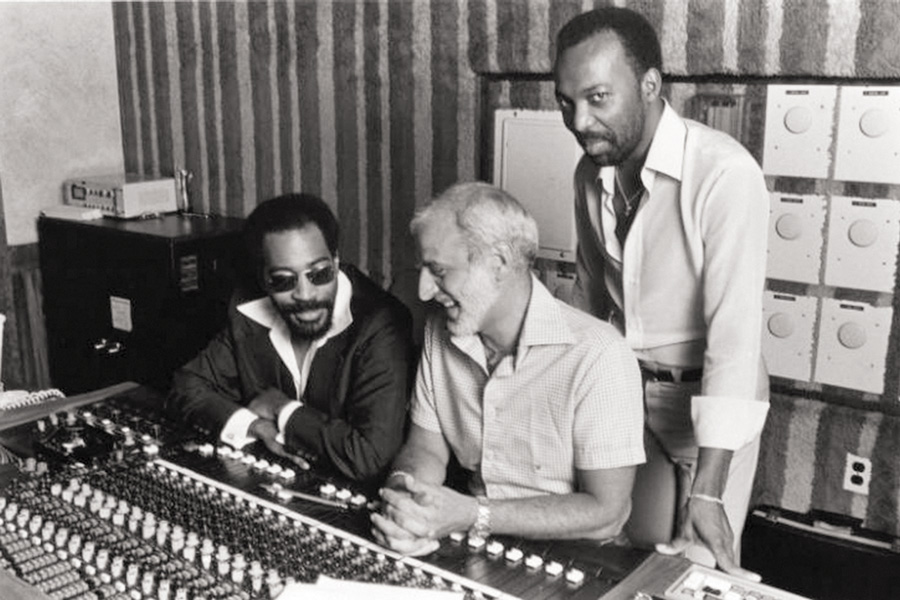

Gamble and Huff with sound engineer Joe Tarsia at Sigma Sound. Photograph by Don Hunstein/Sony Music Archives

Teddy Pendergrass on Soul Train in 1980. Photograph by Soul Train/Getty Images

Patty Jackson, DJ, WDAS-FM: I started deejaying for WSSJ in Camden in 1982, right after I graduated from high school. I grew up in Philly listening to all of the music that came out of that studio. Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes. The O’Jays. Teddy Pendergrass. Lou Rawls’s “See You When I Git There.” Mmm-hmm. [laughs] My father couldn’t sing a note, but he could swear that he could sing like Lou Rawls.

John Oates: All of a sudden, the Sound of Philadelphia is worldwide. No doubt about it. It was totally unique. It didn’t sound like Motown or the R&B in New York or Chicago. It wasn’t the sound coming out of Memphis. Gamble and Huff, with the help of people like Tommy Bell, really created something new. It was a unique combo of African American music and English classical influence. The string arrangements. The orchestra touches. And really, the sound is a reflection of the city itself. They somehow captured what the streets of Philadelphia sounded like. I hear “Back Stabbers” and I hear Philadelphia.

Thom Bell: I heard the future of what music could be, and I tried to write that future. But Gamble, he was the one who heard the future in the music business. Nobody understood the business like Gamble understood the business.

Bobbi I. Booker: You always hear about Lou Rawls and the O’Jays and Teddy. But a lot of people don’t realize that they also worked with the Jacksons. Note that I said “the Jacksons.” Not the Jackson 5. Michael and the boys had left Motown as the Jackson 5 and became just the Jacksons. And Gamble and Huff produced their first album away from Motown. It was simply called The Jacksons, and my favorite tune on it is “Enjoy Yourself.” It really showcases Michael’s vocal acuity and Gamble and Huff’s songwriting abilities.

Leon Huff: When it came to the Jacksons, that was a magical time. I sped into the studio when they came to Philly. We had some great cuts on that album. One of the highlights of my career was definitely working with Michael and his brothers.

Kenny Gamble: The number one thing we had going for us was that we all worked together. There was this mystical kingdom of a thing in the room. How you get along with each other. And the music was established from that spirit. You’re sending out vibrations on a lot of our songs, like the Soul Train intro. “People all over the world”! We wrote that. We were reaching out to the whole world. And they answered us back, because the music wound up all over the world. And it still is. You can’t stop it.

The Legacy

Patti LaBelle: Kenny was very much the perfectionist for my recordings. He didn’t let me get away with it if I was just a little sharp or flat. It was “Do it again.” And then “Do it again.” We did take after take after take. It sounded good to me, of course, but Kenny would say, “Again!” And we would do maybe 20 takes just to get one song.

Kenny Gamble: Patti was just so beautiful and marvelous to work with. She’s a natural-born great artist. And her personality is as great as her voice.

Patti LaBelle: I learned so much from working with them. Mostly: Don’t settle for halfness. Strive for perfection. Listen to “If You Don’t Know Me By Now.” That is a masterpiece. Listen to that orchestration. And it’s so Philly. Nobody does it like Philly.

Patti LaBelle in 1985 at Live Aid in Philadelphia’s JFK Stadium. Photograph by Ebet Roberts/Redferns/Getty Images

Kenny Gamble: Everybody is always in a hurry. They just want to get in and out of the studio. But part of being a good producer is being able to work with everybody. The number one thing you wanna do is get their voice on tape and get it right. Some of the artists, they pick up quicker than others. And then some artists are just in a big hurry all the time. It’s all good. You just have to know how to deal with different personalities and get what you need.

Eric Bazilian, co-founder, the Hooters: What great music they made. I remember a couple of times playing on sessions for other producers who wanted to make records like Gamble and Huff made records, and they couldn’t figure out how to do it. It was just hit after hit. I remember I was once given an audience with Ken. I was 21, and Ken was a bit older. My friend took me to Ken’s office, and he had a suit on and was sitting behind this giant desk. It was very formal, but he was also very friendly. I started telling him about the band, and he asked me, “Do you write songs?” And I told him, well, I had written a few, but I wasn’t really deep down in the trenches with it. And he just looks at me and says, “Just write songs. Just keep writing songs.” And that was the single best piece of advice anybody ever gave me.

Bobbi I. Booker: If you lived in Philly back then, and especially if you listened to WDAS, there were some things that were just standard to you. TSOP, the Sound of Philadelphia. MFSB, which was the orchestra for TSOP. And these were some of the best players you could find anywhere. World-class musicians. And the Sound of Philadelphia became the Sound of Black America once that tune was selected for Soul Train in 1973. People all over the world, indeed.

Patty Jackson: There was always music on at home. And Saturdays were made for Soul Train. The dance shows like that were hot, and hearing “People All Over the World” on the opening was amazing. Soul Train had so much of the Gamble and Huff music, and I used to love watching those dancers dance to those songs and know that those songs were made right here in Philly. It was so different. The instrumentation. The orchestra was something.

Fayette Pinkney, Valerie Holiday and Sheila Ferguson of the Three Degrees sang on the Soul Train theme song. Photograph by Tim Graham/Getty Images

Bobbi I. Booker: Music for my father was a very important part of life. I didn’t want to listen to spirituals and gospel music, but he insisted that I did because of their place in our history. Then in the 1960s and early 1970s, those same things became important to my father with the music that was out there. He wasn’t interested in pop music or nonsensical love songs. He didn’t care for James Brown, but he really cared for James Brown once James Brown sang “Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud!” And with the Sound of Philadelphia, the Black consciousness and the social message was in the music. And that piqued my father’s interest, and once I started choosing my own music, I was drawn to those messages as well. The messages emboldened my Black pride. And when I heard these tunes, I knew that this message went beyond my neighborhood. I knew there were Black folk in New York, in Detroit, in Atlanta, in L.A. The people who were dancing on Soul Train were partaking in this same message, and knowing all these people were out there really emboldened me as I went forth in life.

John Jackson: Everything came together. Everything worked really well. But then around 1975, you lost some of the original MFSB players. Then you lost some of the background singers. And the sound started to change. It wasn’t the same. There’s a point where you can put on a record and then you put on the next record that came out, and you realize: Things are different. There was also a point where Kenny had some personal problems and was out of the studio for about a year. And then of course, you have the Teddy Pendergrass car accident in 1982. Teddy was huge for Philly International. And that loss was a big blow for the label. But looking back, their ratio of hits to misses was still great.

Leon Huff: I wish we had a chance to work with Aretha. We talked about it. And there was an occasion where we were supposed to work together, but Aretha had taken ill, and then things had changed. Aretha did record some of our songs that we wrote, but we never got a chance to work directly with her.

Kenny Gamble: For me, it’s Miles Davis. I always wanted to work with Miles Davis. We had talked about doing it. Fusing Miles Davis with the MFSB orchestra would have been a classic. That man could play the horn. And you close your eyes and just listen. This guy was so weird and unique. I went to see him once, and he never turned around and looked at the audience once. He just looked at the band the whole time while he was jamming.

Leon Huff: The business obviously started to change a lot when the rap era started to happen, and the technology started to change. The way you make records was changing, and we had to make adjustments. I bought me a bunch of machines, all kinds of keyboards and synthesizers and drum machines.

Patty Jackson: It’s also disco. Once disco came around, there were no orchestras. And then there were computers. And sampling. Instead of an orchestra, you could just run something through a computer. And it’s not the same. It’s just not.

Kenny Gamble: I like the old way. You get a better presence. It can, of course, still work and all with digital. There are some good things about digital. But I really liked working with acoustic instruments. Rap definitely changed things for us. They sampled our music, but this was just a whole new sound. Everybody gets their turn, I guess. It’s what you did with your turn when you got it.

From left: Then-Councilmember Jannie Blackwell, Huff, then-Mayor Michael Nutter, Gamble and Jerry Blavat at a 2010 ceremony dedicating a section of Broad Street. Photograph by Gilbert Carrasquillo/FilmMagic/Getty Images

Eric Bazilian: Many years after that meeting in his office, I was at the restaurant Yama in Ventnor with my cousin, and Kenny was there. I figured what the hell, and I walked over to him and introduced myself again. And he said, “Ah, Mr. Bazilian, you’ve done very well for yourself. Have you written for other people?” And I told him I wrote “What if God was one of us.” And he stood up and shook my hand and said, “That’s like that ‘Imagine’ song that guy from the Beatles wrote.” [laughs]

John Oates: The Sound of Philadelphia will hold up forever. The word “classic” gets thrown around too lightly. People wind up using the term “classic rock” to infer that the music is old. To be truly classic, something needs to be timeless. It needs to have a classicism of its own that is irreplaceable. It needs to transcend space and time. And this music is absolutely classic. It will live forever, for everybody.

Patti LaBelle: Kenny and Leon, they just have this thing that is magic. It’s obviously stood the test of time. And it’s gonna stand forever.

Published as “People All Over the World” in the April 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.