Inspector General: City Failed to Properly Vet Philly Fighting COVID

"Simply put, there is no question that the City of Philadelphia should never have been so closely aligned with PFC," the city inspector general concludes, though he stops short of recommending any disciplinary action.

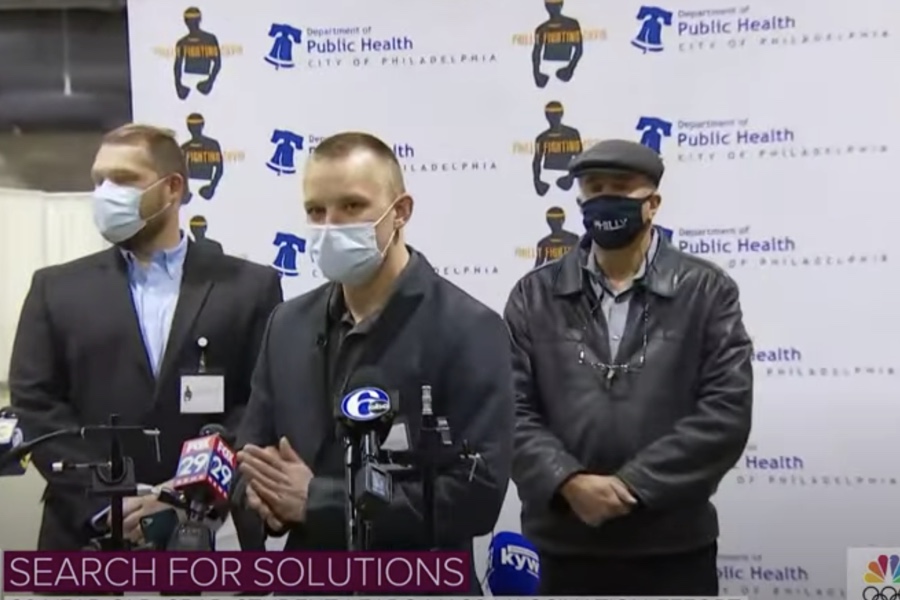

An independent investigation by the city inspector general concludes that the health department should never have given Philly Fighting COVID the opportunity to run a vaccine clinic. Screenshot via YouTube.

In the aftermath of the Philly Fighting COVID vaccine-clinic scandal, there was one main question on everyone’s mind: How the hell did this happen? Health commissioner Thomas Farley said he didn’t really know, and his deputy health commissioner handling the vaccine rollout, Caroline Johnson, had already resigned. So in came the city inspector general (at Farley’s request) to begin an independent inquiry into PFC and its relationship with the health department.

On Monday, inspector general Alexander DeSantis released an initial report of his findings. In it, he stops short of saying Farley or any other current health department employee committed acts worthy of discipline. But he also outlines a series of new revelations and warning signs that went ignored by health department officials. DeSantis paints a picture of a health department that was decentralized, poorly organized, and ultimately incapable of processing the multiple clear warning signs that should have indicated that Philly Fighting COVID wasn’t an appropriate group with which to partner on a vaccine clinic. “Simply put,” the report concludes, “there is no question that the City of Philadelphia should never have been so closely aligned with PFC.”

Here are the three biggest takeaways from the report.

There Were Known Problems With PFC Before Vaccinations

Prior to the vaccine clinic at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, Philly Fighting COVID had been running testing sites for months. Those sites, paid for in part through a city contract worth more than $190,000, seemed to run reasonably well, DeSantis found. But there were some signs of inexperience. In August, PFC arranged for a pop-up testing clinic in Society Hill and later attempted to bill the city for its testing; the health department had never authorized PFC to perform tests in Society Hill in the first place.

Months later, when the health department sent a “secret shopper” to PFC’s main testing site at the Fillmore concert venue’s parking lot in Fishtown, the undercover observer noted that there was virtually no signage, that the group was not responsive to an email inquiry, and that there was little information on the website about walk-up appointments or testing clinic hours.

The report also suggests that PFC struggled to comply with basic record-keeping and data requirements. Invoices sent to the city often contained mistakes, and while PFC was supposed to be collecting demographic data on its test recipients, it managed to do so for just 32 percent of those it tested. Compared to other testing providers in the city, DeSantis found, PFC had the “lowest reporting percentage by a significant margin.” The Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, by comparison, recorded demographic data on upwards of 90 percent of those it tested.

The Health Department Failed to Properly Vet PFC

One of the main themes throughout the report is the general lack of organization inside the health department. Department employees who had worked with PFC CEO Andrei Doroshin on testing expressed doubts about his competency and concerns over his lack of professionalism but failed to share that information with the separate group of employees working with PFC on vaccinations. “There was never a structured opportunity for the two groups to share information about Doroshin and/or PFC, particularly at a leadership level,” the report notes. (Doroshin declined to participate in the investigation, according to DeSantis.)

The report also calls into question the lack of a formal vetting process. While Doroshin began talking about plans for a vaccine clinic as early as August, his plans were never reviewed through a formal request-for-proposals process. In late December, when the health department reached out to PFC about the prospect of running a vaccine clinic — on just two weeks’ notice — all PFC had to do was submit paperwork to the CDC that affirmed it had a licensed physician and proper cold storage. “Whatever confusion arose, it was due to the fact that the health department had not robustly evaluated PFC (for vaccination work) via a structured, documented, public and well-reasoned mechanism,” the report concludes.

There were other signs of an institutional disconnect. On the eve of PFC’s first vaccine clinic, Farley didn’t find out about a scheduled press conference that would feature the Mayor and Deputy Health Commissioner Johnson until the night before. And while Johnson knew about PFC’s shift to for-profit status and didn’t seem to think it was a problem at all, seeing as the city routinely provides vaccines to for-profit entities like pharmacies, other city officials felt blindsided by the change.

Finally, just five days before the start of PFC’s first vaccine clinic on January 8th, the group’s chief medical officer resigned and called a city official to express his concern about the company, its for-profit status, and its general ability to manage a high-profile vaccination effort. That message apparently never made its way to Farley, and it wasn’t until January 25th that he changed course and decided to cut ties with PFC. “This was a serious red flag that should not have been ignored,” the report notes.

IG Stops Short of Calling for Discipline

The inspector general ultimately concludes that the decision to partner with PFC for testing wasn’t necessarily a mistake. He also writes that the decision to cut ties with the group was a sound one and gives Commissioner Farley faint praise for being the “most cautious voice within the health department.”

At a press conference on Monday, Mayor Jim Kenney defended Farley’s overall job performance throughout the pandemic while conceding that his health commissioner was at times “disconnected and uninformed” about the ongoing vaccine effort. Farley, too, suggested that the problems stemmed not from any individual decision-maker but from the structure of the health department itself. “Rather than blaming individuals,” Farley said, “I think the appropriate response is to try to fix processes and the structure so that we cannot make this kind of mistake again in the future.” Farley outlined a number of suggested reforms, including increasing the size of the health department group working on vaccinations and ensuring that a representative from City Council be involved with all future city-funded vaccine efforts.

DeSantis says this is is just a preliminary report and that his office’s investigation remains ongoing. You can read the full report here.

This story was updated to correct the health department secret shopper’s findings at the PFC testing clinic.