Chef Omar Tate’s Plans for Philly Go Well Beyond Food

Chef Omar Tate has big plans for Philadelphia. Photograph by Marcus Maddox

[Wall Street]

This story starts the way every story must start in this day, this age. Restaurant stories in particular, but really, every single story of any kind. It’s a disaster story. A love story. A food story. It’s about memory and family, fame and power, collard greens and potato salad. And it begins in a penthouse on Wall Street, Manhattan, USA, high above a site where, once upon a time, grain and oysters and Black people were bought and sold.

[New York, New York]

It starts in March. Early March 2020 — which, as we all know now, is a very different place than mid-March will be, or late March. It starts at the end of a certain kind of world.

Partnering with a company called Resident, chef Omar Tate was cooking a series of well-attended high-end dinners for groups of 10 or 20 at a time. They happened in luxury apartments on the Upper West Side, in Brooklyn, wherever. The series was called Honeysuckle Pop-Up, and he was getting $150 a head for “New York Oysters” with thyme and cream, smoked turkey neck over beans (a dish named after the MOVE bombings, dubbed “Smoked Turkey Necks in 1980s Philadelphia”), roasted yams inspired by that scene in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, buttermilk-fried rabbit (which he called “Bre’r Rabbit”), and a course named “Remnants on a South Philly Stoop” — crab, sunflower seeds, charred lemon and garlic powder. There was Kool-Aid (his version) on every table, and ice cream for dessert, flavored with honeysuckle.

Omar had curated the art on the walls, the music coming out of the speakers. Every menu was deeply personal, deeply historic, and came “from a distinctly Black perspective.” He’d handwritten poems to guide people through the biographical experience of dining at Honeysuckle, in this pocket universe of Kool-Aid and collard greens he created in borrowed spaces. It was part dinner, part theater, and around the time he’d moved the Omar Tate Show to the Wall Street space — to an apartment overlooking the former location of one of Manhattan’s most notorious slave markets — he was publishing, speaking, meeting people. The New York Times was writing about him, and he was starting to work on a project with the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. He was hustling. He was right on the verge of blowing up.

But instead, everything else did.

Esquire, April 30, 2020

Honeysuckle was real. It was peaking as an event and as a philosophy. I had been adding to the conversation of power shifting. I was rubbing elbows with “important people” on the outside. Inside I was rubbing sticks together for fire. I was behind on my rent and living contract to contract. When the pandemic hit, I lost all income that was projected for the next six months with little left to stand on. I entered March with about two thousand dollars in my bank account wondering what my future was to be. The important conversations with all of the important people don’t seem to matter much anymore.

— Omar Tate

[Philadelphia]

On the phone, I ask Omar how he got started. How he ended up cooking.

I tell him, “Some people choose cooking, I know. They love it young. They go to school or whatever.”

“That wasn’t me.”

“And there’s this … this narrative about growing up watching your mother cook or your grandmother cook and falling in love with it.”

“Yeah.”

“That’s the sort of traditional arc of the chef story, right? But so much of the time, it’s just such utter bullshit.”

“Total bullshit.”

“Right?”

Because sometimes (a lot of the time), people don’t choose kitchens. They just end up there. It’s circumstance. Willingness. A lack of any other viable options. Sometimes it’s luck. Restaurant work, hotel work, at a certain level, it’s a meat grinder. It takes people in, chews them up, and spits them out again. And the machine always needs fresh bodies.

Omar laughs. “I was a drug dealer, but I was really bad at that. So I was looking for work. My first real job, I was 17. I was a porter at the Philadelphia Marriott. I worked overnights at the Rittenhouse Hotel.” Those weren’t cooking jobs, but they were service jobs — washing dishes, scrubbing the stainless, deep-cleaning. He was in the kitchens, even if he wasn’t on the line. “And that proximity to kitchens allowed me to lie on my résumé and say I could cook.”

He had a choice: There was a job at the Crowne Plaza, doing the same thing he was doing, for $12 an hour. And there was a job at the RiverCrest Golf Club and Preserve, as a cook, for $10. The Crowne was on City Avenue. The RiverCrest was in Phoenixville, two and a half hours away by public transit.

“I chose the cook’s job because the journey of going from a cook to a chef was something I could envision. That I could define.” Plus, Omar had a son, Bashir, who was 10 months old then. He thought that cooking was something he could teach the kid someday — was a skill beyond making the stainless shine. He thought cooking was a path to being able to pay the bills, to sending Bashir to college someday. Omar had plans.

So he chose kitchens. He chose the kitchen because the kitchen was where he already was and where he could see himself. Because the kitchen was a story that he already knew the bones of, and with a little hustle, a bus pass and a few small lies, he thought he could slide himself inside without anyone noticing.

Omar Tate preparing pies at South in Fairmount. Photograph by Marcus Maddox

[Wall Street]

Omar wrote his last New York Honeysuckle menu in February. It was 10 courses, eight of them inspired by song or album titles. (The last two were desserts.)

The gig at the NMAAHC would’ve brought in enough to pay the bills, clear some debt, get even, maybe. The money would’ve buoyed him up for the season, kept Honeysuckle going.

But then March. Fucking March, right? Can you remember the moment? The one where everything turned upside down? Everyone has a story. Those of us who live will carry it with us forever.

“Once I realized the pandemic was real, all I could think about was my son. I was in Brooklyn. He was here. I pretty much immediately left my life, and I came home.”

[Phoenixville, Berwyn & Philadelphia]

“Shallot,” Omar says. “Fucking brunoise. I don’t know what either of those words means.”

Not now. He knows what they mean now. This is before. This is the 2000s, Phoenixville and Berwyn and Old City and Walnut Street.

“When I stepped into that space” — and he means kitchens, all kitchens back then, but the RiverCrest kitchen in particular — “I let my whole self go. I was assimilating. I listened to different music. I talked different. Yes, Chef, no, Chef.”

He didn’t know where anything was or where anything went. He didn’t know how to use any of the equipment. He didn’t understand the rhythms of the line, or the language spoken there. He had to make himself into a new character to fit into this story, and he did. Fourteen hours a day, five days a week — not counting the commute. He was only paid for 40 hours (a story as old as restaurants), he got screamed at, but he learned. Omar was born in Philly, raised in Philly, educated in Philly. Now he was going to be trained in Philly, too.

After the RiverCrest, he went to Berwyn. To Nectar, at the height of Nectar being Nectar — which means something to people who understand local restaurant history and maybe nothing at all to people who don’t.

“Two hundred twenty seats,” he says. “Four, five, six hundred covers on the weekends. Nothing but Land Rovers and Benzes out front every night.” He worked hot apps and grill under chef Patrick Feury.

“When I got to Nectar, I had my skills. I knew the names of things; I knew what the equipment was.” He walked like a cook and talked like a cook and worked like a cook, but it wasn’t enough. Wouldn’t be enough, maybe ever. Because he was also a Black man cooking.

“The very first time I remember talking about food, I remember being in that kitchen.”

Talking about food meaning, you know, actually talking about food. Talking with other professionals. Sharing ideas. As a peer.

“I was making sausages. They were like Toulouse sausages, you know? And we’re all standing around tasting it, and Patrick comes over. I wanted to talk with him about it. And he takes a bite, and he goes … You know those old breakfast sausages? The frozen ones? They were cheap grocery-store shit. Called Brown ’N Serve?”

I tell him, “I know Brown ’N Serve.”

“Right. He says, ‘Tastes like Brown ’N Serve!’ And then he walks away.”

“Jesus.”

“And it’s like, I was trying to connect with you, man. I was trying to have a conversation that wasn’t, like, work-related. It was kind of crushing.”

And it would happen again. And again. And again.

At Fork (under a different Feury now — Terence this time), Omar worked garde-manger. He was cooking the staff meal one time, and he made potato salad. He made potato salad like he remembered his neighbors making. Block-party potato salad. “And he liked it, man! That was a big deal to me. That was huge.” But he asked what kind of potato salad it was. Where it came from. And Omar explained — told him how this was his Block-Party Potato Salad.

“I had to explain to him what that was,” Omar says, still a little disbelieving a decade later. “The fact that he even commented on it was strange. It was an exchange that was just condescending. That’s what that was.”

Because Omar Tate’s food was not allowed to be food under the definitions of a fine-dining kitchen. Because his lived experiences were not accepted as legitimate experiences. A thousand chefs have made motherfucking bank trading on their food memories. I’m one of them. But then, there, in that place and at that time, Omar’s were … invalid. They didn’t count.

“I had a duality, or even a tertiary existence in this world that I tried really hard to get into.”

He was a cook, sure. But first and foremost, he was a Black cook. That was what everyone saw.

[Wall Street — An Aside]

We’re talking about Honeysuckle, Omar and I. About what it was like there when everything was good. About what it meant. I ask him if it was weird, looking out over those tables covered in bean pie and biscuits, smoked squab with stew greens and salads inspired by Black chef and author Edna Lewis, and seeing all those white faces, all that corporate money.

Omar Tate’s end-of-summer tribute dinner to Black life in Philadelphia, a pop-up hosted at Plowshare Farms in Bucks County last year. Photograph by Ryan Collerd

Photograph by Ryan Collerd

Photograph by Ryan Collerd

He says yes, but no. No, but yes. Of course. Totally. And then he tells me a story.

This one night, he says, there was a woman who complained about the price tag: $150 a head, $300 a table. And for what? For Black food? For collard greens? The collards, in particular, seemed to really get under this woman’s skin.

And Omar explains. He says to me that the ingredients were foraged locally. The greens were from a local farm. He’d made the vinegar himself. He tells me all the steps he went through to make those collards — including how he learned to make collards, the research, the study.

He says, further, that the way these dinners work, he comes out onto the floor. He explains everything to his guests. So this woman, she had all the information that he just gave to me, and still she couldn’t see it. It didn’t matter that this was just one part of an eight-course meal cooked by a chef with nearly 20 years in the game. It didn’t matter that it was done with professional technique and deep concern. It didn’t matter that it meant something. This was Black food, and Black food, to her, was just worth inherently less than, say, French food. She felt cheated. Nothing ever changes.

But Omar says it didn’t matter. It stung, of course. But it didn’t matter. That woman? She’d shown up. She’d paid. She’d had the experience that Omar wanted to give her.

“Whether she liked it or didn’t, I still won.”

[Philadelphia & New York]

At Fork, Omar had a rough time. After months, he was still on the garde-manger station. “He wasn’t never moving me off garde-manger,” he tells me. “I wanted to use hot shit. I wanted to learn something new.” So Omar demoted himself. He volunteered to do the breakfast-and-brunch shift — and in the restaurant world, no one wants to do the brunch shift. That’s the worst gig. A punishment assignment.

And it sucked because of course it sucked. It’s not even something we talk about, because it isn’t something we have to talk about. He would come in, do prep, cook through the service. At some point every morning, Terence would come in. “He’d ask me to make him an omelet, then throw it away and tell me it was shit. I got really good at making fucking omelets, man. They were like paper.”

We laugh about it, because these stories? They’re not all bad stories. Cooking, at a certain point in every serious chef’s career, becomes like something out of a kung fu movie. There’s a moment (or multiple moments) where the aged kung fu master just hits his fucking apprentice over and over and over again with a stick, where he tells the apprentice that he’s shit and will never amount to anything, that he can’t learn, won’t learn, is incapable of learning and should just quit. Give up. Go home.

But the apprentice doesn’t quit. The apprentice gets better. He becomes unstoppable. He surpasses his master and goes on to avenge his family or defeat the evil wizard or whatever has to happen next.

“They’re kitchens,” Omar says. “It’s not like the story ends with and then I went to HR. As terrible and toxic as kitchens are sometimes, I have no regrets.”

After Fork, Omar was a tournant and saucier at Farmer’s Cabinet. He cooked for Andrew Wood at Russet, worked at Buddakan, staged at Le Bec Fin under Nick Elmi.

He went to New York in January of 2013 because that’s what young chefs do. Like a rite of passage: leaving the nest, the hometown, heading out into the world to seek your fortune. He bounced around, working wherever he could, in whatever kitchens he could find — a little Italian here, a little Spanish there, bakeries, cafes. He was learning, honing his craft, but at the same time, he was looking for something.

I’m not sure if he knew what it was then. I don’t think he was sure, either — not in any specific terms. But it started with the looking.

The looking was what was important.

[At Home, in West Philly]

When COVID hit, Omar went home — back to his mom’s house in Mantua. She’s an essential health-care worker, working with people with mental health Issues, and he moved into a spare room. He had a bookcase and a mattress, the clothes on his back, not much else. When he said he looked at his life in New York and just walked away, he walked away. Just turned on his heel and left it all behind. When he got here, he took a job delivering for Caviar.

From Wall Street to your doorstep, just like that. From the New York Times and the James Beard House to an empty bedroom and counting up his tips at the end of the night. To him, the Caviar job wasn’t a lot different from what he’d been doing. “I was in service to people,” he tells me. “I’ve been conditioned to do that for more than half my life.”

Instagram, March 28, 2020

I went out for a cup of coffee today

A risk for a bitter taste of normalcy

I was told that there was no more

That’s when I knew life would never

be the same ever again

— “Styrofoam,” by Omar Tate

[Philadelphia]

The conversations, phone calls, emails, texts are sporadic, come in bursts. I’d told Omar when we started all this that I wasn’t really doing an interview — that none of this was an interview — but that I just wanted to talk. The ’rona has fucked up everything. How we work, how we communicate. The isolation that everyone was feeling? It was a part of this, so that when we would connect, our conversations were like loud music heard from a passing car, like finding someone else’s photographs scattered on the bar. The conversations are interruptions in the grind of quarantine, of pandemic precaution. Windows looking out on someone else’s yard. And the story, whatever it was going to be, would just come together. We’d will it into being, together.

“I’ve never been afraid of taking a step back,” Omar says to me one afternoon when we’re talking about something else entirely. About comics, maybe. Or kitchens. Asshole chefs and their asshole ways. About menus.

And then one day, Omar just goes dark. Stops responding for a week, week and a half. It’s nothing at first. Things are busy. Things are weird, because they’re always weird now. I send a couple of emails, hear nothing back, send a couple more — cool, casual, but fuzzy with a kind of background panic. A frisson of stress.

JASON SHEEHAN

TUESDAY 7/31/2020, 10:21 P.M.

TO: OMAR

Just checking in. Making sure I didn’t weird you out with that long email the other night. I figure you’re busy, but I just wanted to make sure that a) you saw the last email, and b) I didn’t scare you off. Let me know what’s up.

— Jason

JASON SHEEHAN

WEDNESDAY 8/5/2020, 3:08 P.M.

TO: OMAR

Omar,

Got any time to talk today or tomorrow? I just cleared a couple deadlines, so I’m pretty wide open at the moment.

— J

And I’m thinking, Did I do something wrong? Say something wrong? Because I’m bad with people sometimes. I assume there’s more of a connection than there actually is. I talk too much. I’m too coarse. And this distance? These phone calls — these removes made necessary by pestilence and plague? Fuck.

JASON SHEEHAN

TUESDAY 8/11/2020, 11:37 a.m.

TO: OMAR

Omar,

If you have any time today, I’m pretty much wide open. Failing that, how about tomorrow sometime between noon and 3 p.m.? My deadline on this piece is the 15th. I can probably beg a couple extra days if I have to, but things are starting to get a little tight.

Plus, this is fraught, right? I mean, let’s be honest here. This is 2020, and I’m the white food writer in a largely Black city talking to a man whose food — whose entire reason for cooking — is rooted in the one thing about him I can never understand no matter how much we talk (or don’t), no matter how much he writes (or doesn’t). And I will never capture from him (borrow from him, tease out of him) an nth of what that experience is.

“I get a different kind of news,” Omar wrote in a piece for Esquire in April. It was a refrain, a motif, a well he returned to again and again in order to capture what living in his skin is like. When he talks about his uncle dying of COVID — 77 years old and already in the hospital because of complications from diabetes. I get a different kind of news. When he tells me about his cousin and his cousin’s drama with unpaid child-support payments and how that happened and why that happened and then says, “I could spend a year trying to explain his situation to you and you wouldn’t understand.” I get a different kind of news.

And all of that just means that the world is coming at him from a different angle, on a different wavelength, that I am never going to see. It means that our consensual reality really ain’t all that consensual, right?

The Next Morning

I get a text from Omar:

Hey Jason, sorry about that. This week was just not a great week for work stuff. I don’t remember if I told you but I got married yesterday.

[New York, Bucks County, Orangeburg & South Carolina]

In New York, Omar was doing research. While he was working, while he was paying the bills, doing 14-, 16-, 18-hour shifts and trying to hold things together with both hands, he was studying, searching. And the thing he was looking for was himself.

No, that’s not poetry. That’s not cleverness. That’s truth. He was looking to find pieces of himself on plates, in menus. But before he could find that (or not find that), he had to learn how to recognize it.

“I open myself up to possibilities because I don’t fucking know shit. I don’t.”

On the phone, Omar is telling me about research. He says, “I went to this museum and told the librarian I wanted to know about Black food and Black culture and Black life. And she gave me, like, 80 books. She just loaded up a dumbwaiter and dropped it on me.”

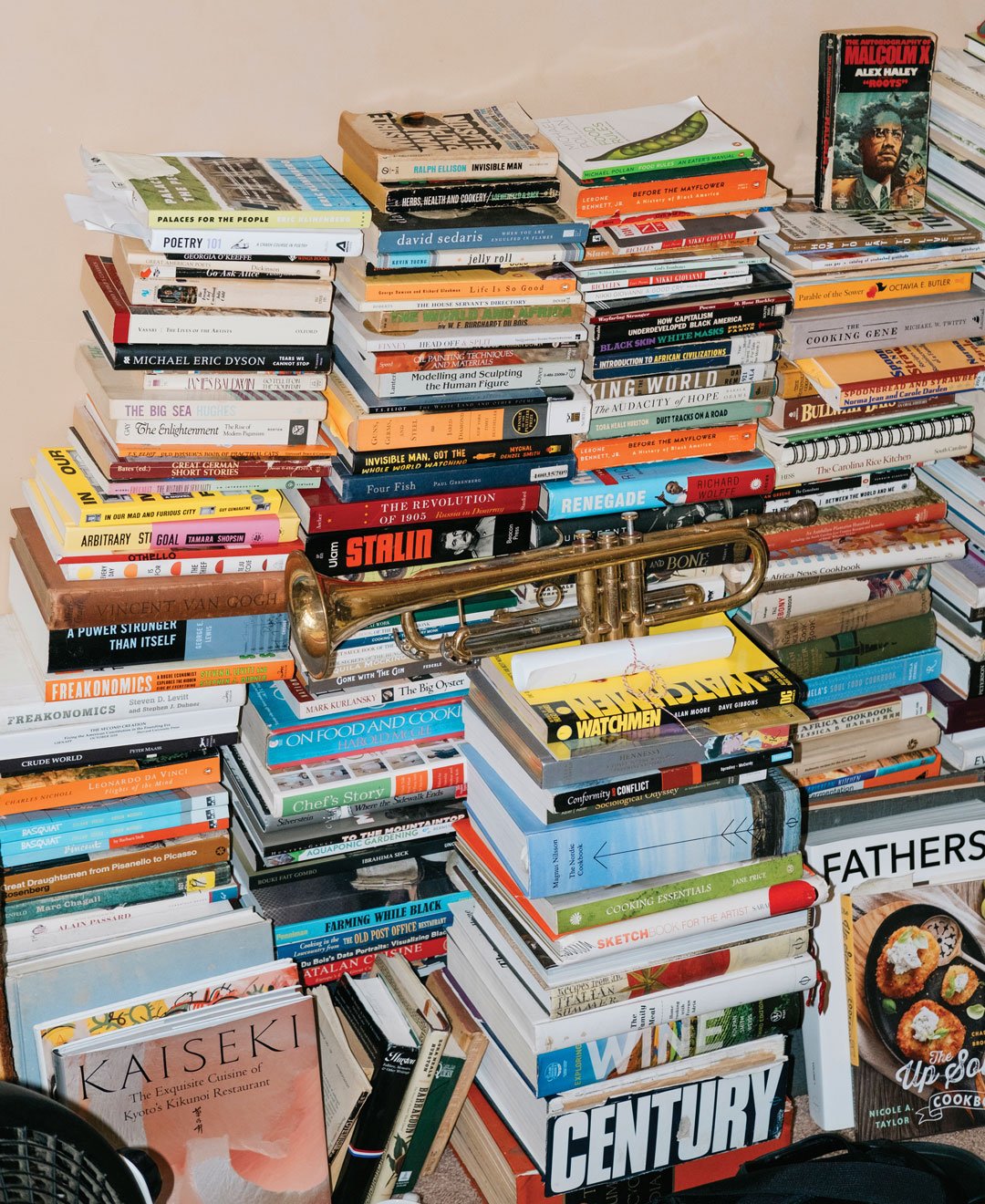

A collection of Omar Tate’s books that inform his Honeysuckle Pop-Up menus. Photograph by Marcus Maddox

He’s telling me about Edna Lewis and Zora Neale Hurston. About J.J. Johnson, who opened the Cecil in Harlem in 2013, doing Afro-Asian fusion, and for whom Omar would go to work when Johnson went to the Henry at the Life Hotel in Manhattan to cook the cuisine of the African diaspora with an Asian accent.

“Fundamentally, it was the same,” he says of the experience — of the kitchen and its rhythms, “but it was also different. He would put bird’s-eye chilies in the mirepoix.” Which might seem like a little thing unless you’ve been a chef, been trained French, had the French canon and French technique beaten into you every day of your life, because then, messing with the mirepoix? That’s a signifier. A magnesium signal flare denoting a point of unmistakable departure. The huge-est thing in the world. Pete Wells reviewed the Henry for the Times and gave it one star.

But Omar’s head was already in a different place. He was traveling all over the South. He went to South Carolina and found the names of his enslaved ancestors written in the records of the Orangeburg Presbyterian Church — their given first names and then their master’s last name written next to them, in parentheses: Jamison.

Jamison was a physician, Omar tells me. He lived in Bucks County: “Then he moved to South Carolina and enslaved my family.”

Omar went there, to the property that Jamison owned in Orangeburg, South Carolina. He walked on the ground his ancestors walked. And it’s just woods now. Weeds. “But I found the gravesite of the family that owned my people.”

Omar’s mother’s and father’s families were both in Orangeburg as slaves. Three hundred years later, his mom and dad met in South Philly and made Omar, who would later walk in Orangeburg and go back to Manhattan and realize that what was missing on all those plates, on all those menus, was a representation of him.

He emails me: I felt that there was no representation of my Black life in food. In searches prior to my pursuit of Honeysuckle I found all of the Black representations in fine dining or that arena to be Southern or West Indian. I felt like I had no place as a Black person from the North.

Honeysuckle would fix that.

Remnants on a South Philly Stoop, Honeysuckle Pop-Up at Craft New York City, May 2019

The professional kitchen has been home to me for at least a third of my life. Unfortunately, that home has not loved me or people who [come] from where I come from as much as I loved it. I wanted to create a dish that represented my life, my family, and my environment. I am not a farmer, my parents didn’t have money or own a restaurant, I did not stand by my grandmother’s side while she made Sunday supper. I’m not African or West Indian or anything else. When people ask me where I’m from, I respond I’m from Philly. This dish represents the migration of my family from their home in Charleston, SC, ninety years ago to Philadelphia. Philadelphia where the crab man on the corner still exists, where we sit on the stoop or porch and chew on salted sunflower seeds in the summer and spit out the shells. Where we season our shit with old bay and garlic powder. In Philly where we still read the oldest black newspaper in the country, the Philadelphia Tribune. It’s all on this plate. Deviled blue and snow crab, candied charred lemon, fried parsley, sunflower seed purée, toasted sunflower seeds, handmade garlic powder, and handmade old bay.

— Omar Tate, via Instagram

[Philadelphia]

“You got married! Congratulations, man!”

“Thanks,” Omar says, laughing.

“How did that happen?”

So he tells me. Her name is Cybille St. Aude, and she’s a chef, too. From Long Island. She writes children’s books, cooks Haitian food, co-founded Earthseed Provisions in New York. The wedding “was planned for maybe two months, but it’s COVID, so … ”

So it became a small thing, a double party split between their families in Philly and on Long Island, and they’d spent the week bouncing back and forth.

“We’ve known each other for six months,” he says. “It was love at first sight. And with COVID happening, every day is like a year, so in June we said fuck it. Let’s do it.”

[Bushwick & the Italian Market]

Omar started doing pop-ups while he was still working at the Henry. The first official Honeysuckle dinner happened in November of 2018, in Bushwick. Then came one at Cristina Martinez’s El Compadre here in the Italian Market.

The menu was personal, intellectual, recursively self-referential, fragmentary in the way a poem can be, like little flashes of connection to time and history. Red Kool-Aid like the kind Omar mixed up as a kid in his mother’s kitchen for family dinners. Beef tartare masked in black squid ink, inspired by Clorindy: The Origin of the Cake Walk — the first Broadway show with an all-Black cast, conceived by Paul Laurence Dunbar and Will Marion Cook over a meal of beef, bell peppers and beer and performed (partially) in blackface. Roasted yams grown from heritage seeds that came, unadulterated, across time from the antebellum South and across distance from Manning, South Carolina. (Omar drove 36 hours, round-trip, on his days off from the Henry just to pick the sweet potatoes up from a friend he’d made while traveling.) The grilled whiting was a riff on his mom’s recipe for fried fish (he called it “Un-Fried Fish”), and a biscuit with sorghum molasses butter and damson preserves was named for his great-great-aunt Ella, who lived in South Carolina and died at 105. Omar never met her, but he knew her. He knew the stories. The history.

Omar tells me, “A recipe is just a recipe. But if you look close at it, there’s a story between the lines. The story of how I got here is the food I want to make.”

In 2019, the Henry closed. Omar had already been doing his Honeysuckle dinners on the side, but now he threw himself into it full-time. He signed on with Resident, which, according to the company website, provided “bespoke culinary experiences in unique residential spaces … [that] bring inspiring chefs and curious epicureans together.” That language sounds laughably arch now. Dated. Stuffy in a top-hats-and-ascots way that’s borderline discomforting — like it was a business built to serve only the Monopoly Man and his robber-baron friends.

Doubly so because even back in 2019, the beginnings of this story and the end of that world were already lurking. The pieces of it were being put in place. Coronavirus was like a future date crossed out on a calendar, so far away until suddenly it’s right on top of you. And the roots of that last Wall Street dinner existed in the first Honeysuckle pop-up — its end already written into its beginnings.

“A recipe is just a recipe,” Omar says. “But if you look close at it, there’s a story between the lines. The story of how I got here is the food I want to make.”

[Philadelphia, today]

There is another world where the pandemic never happened. An alternate dimension where Trump and lockdowns and midnight sirens and 180,000 dead are not our history, our reality. Where Omar Tate’s Honeysuckle pop-up went its way, growing and building. Where he met all the right people, did his gig at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, stayed in Brooklyn, became a success, continued shifting the conversation about food and Blackness at $300 a table.

But in that world, we don’t have this world — the one where Omar came home, married Cybille, started doing his pop-ups out of South Philly Barbacoa for neighbors and friends — smoked lamb marinated in palm oil, chowchow, fried okra and oysters, spring salads topped with snow crab and lemon, whole perch stuffed with callaloo. His menus are all-in for 40 bucks now. They’re meant to feed multitudes.

When we talk about it, he tells me this was always part of the plan. That he always intended to come home and bring Honeysuckle with him. He’d been thinking about it even before coronavirus. He’d been talking with Andrew Wood, was thinking about moving it permanently into the old Russet space, was thinking about lots of things.

“I was putting things in place,” he says. “Talking to people. I would’ve been pollinating the whole country with Honeysuckle. Then the pandemic happened,” he says, laughs. “That changed things.”

So now, he has the weekly pop-up in South Philly. Just before he got married, he launched an ambitious GoFundMe campaign to raise money for the Honeysuckle Community Center — his vision for the future. A combination grocery store, meat market, cafe/library and supper club.

“I’m using the word ‘community center’ because I want it to be about social activation. Food-focused, but I want to be able to hit people in the community at every single economic level.” To bring fresh groceries to Philly’s food-desert neighborhoods, to offer quick, affordable lunches in the cafe, to bring in artists and writers to speak to the people, and then do Honeysuckle-style dinners at the supper club that will bring some of that big money back to his neighborhood.

“I was never interested in opening a traditional restaurant,” he explains. “Because traditional restaurants have not historically served the community — particularly the Black community.”

The GoFundMe is rolling. It had brought in just shy of $63,000 on the last morning we talked — shouting at each other and dropping calls while Omar walked around Esposito’s market, scoring a great deal on chicken for the Haitian/French Creole dinner he was doing that night at South Philly Barbacoa with Cybille. His goal is $250,000, which will be enough for him to buy a space for the community center. Enough to own it outright.

“The most important thing for me is to own the space,” he tells me. “Because that’s the whole thing. Black people don’t own their own spaces.” Which is also why he turned to a funding platform. His original thought had been to do it all himself — to go city to city, hustling. Selling bean pies. Cooking meals to raise funds and raise awareness. Logistics killed that plan. COVID killed it. “It was too much. There’s not enough Omars to do everything I need to do. People want to help me, but I have no money. No money, no space, no nothing. I’m in this weird gray area. It’s like, I don’t want to have someone come and cook with me and then not be able to pay them a wage. That’s not right. I have all the thank-you dollars in the world, but that’s all I got.”

So at home, in Philly, he has the GoFundMe, which, now, he thinks was the right choice. Sixty grand in the first two weeks? It’s hard to argue with that. And it brings the community together so that “we can all own a little piece of it.”

Which, ultimately, is the victory that comes out of all this. The happy ending in this darkest timeline. Out of years of hustle, insults and shame, of potato salad, collard greens and Kool-Aid, of graves and slaves, pandemic and plague, comes hope. A fresh start. A future for himself, his community, his family.

“It’s never been about me,” Omar says. “It is about and of Black culture first, period. It is about Black people. It’s about legacy. It’s about pushing forward. I look at Black history as a written record by Black people primarily over the last 120 years. Before that, our history was recorded by other people, or it was destroyed. I want people a hundred years from now to look at this as a building block.”

He pauses.

“I want Bashir to say, ‘Man, we’re doing something important. This matters.’”

Published as “Remnants on a South Philly Stoop” in the October 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.