Here’s What You Really Need to Know About That Viral Mask Study

A neck gaiter didn't perform well in the Duke University study everyone is sharing online. But the researchers weren't really testing masks.

Masks for the prevention of COVID-19 as tested by Duke University School of Medicine. | Photo Credit: Emma Fischer, Duke University

We’ve been saying it for a while now: We all should be wearing masks in public spaces (as have the City of Philadelphia, the governor of Pennsylvania and the CDC). Hell, we even wrote about how to pick a “breathable” running mask. And to the best of everyone’s knowledge, this was sound advice.

“Masks and other face coverings are worn primarily to protect others from potentially infectious respiratory droplets or secretions from the person wearing the mask — this is source control,” says David Pegues, a professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pennsylvania. “Neck gaiters and fleeces are popular for recreational use in part because they fail to restrict air flow and are easier to exercise in.”

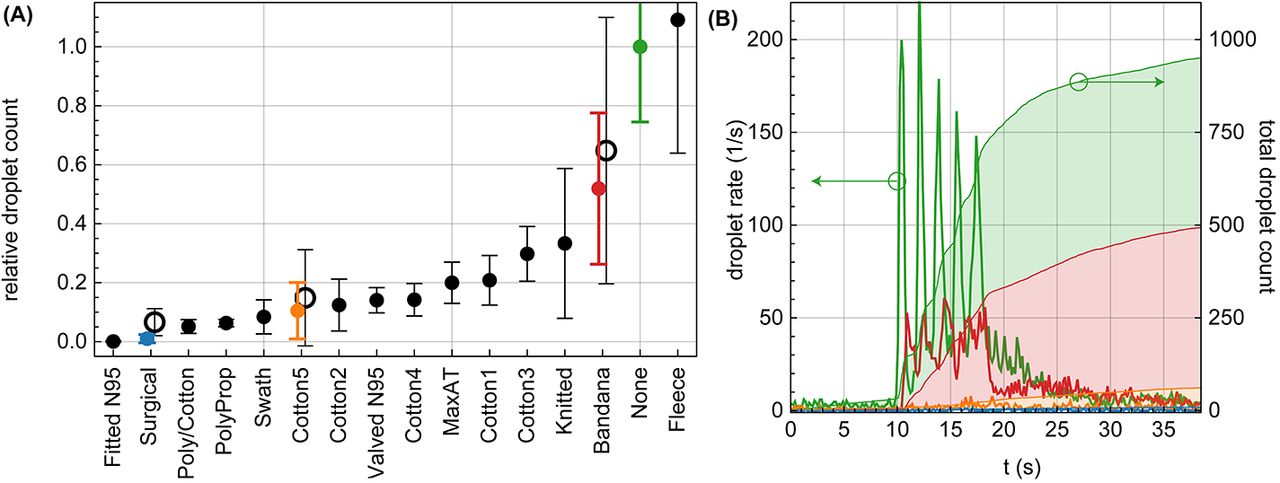

But a new study out of Duke University School of Medicine, published in Science Advances a few days ago, shows that all masks might not be created equal. And, unfortunately for runners — or anyone else who has been using a neck gaiter as a mask — at least one type of neck gaiter, also known colloquially as a “buff” (after the brand BUFF), seemed to test as the least effective form of mask.

The study itself is nuanced and doesn’t exactly lend itself to simple conclusions — more on that later — but one of its findings seemed to suggest that running gaiters and buffs offered very little protection, and could even be worse than wearing no mask at all where the dispersal of droplets is concerned.

“Unfortunately, because of the fabric weave and poor fit around the nose and chin, neck gaiters and fleeces appear to be the least effective face covering, allowing more potentially infectious respiratory secretion to escape,” says Pegues.

This finding means that certain breathable neck gaiters, fleeces and buffs could potentially be, well, a big problem — whether you’re running, wearing them to the grocery store, or pulling one over your face when you stop in to get your coffee from Rally or ReAnimator.

The Duke study explains that the gaiter was found to disperse an average of more droplets than no mask at all — and this was when the subject was not exercising. It’s important to note that this study only tested one neck gaiter — there are likely many similar styles and brands out there that are made of sturdier materials that would perform better.

“The bottom line is they tested one neck gaiter, made of one material, with a pretty rudimentary particle measurement device, and only in one direction of flow,” says Peter DeCarlo, a professor of environmental health and engineering who studies air quality and aerosol particles at Johns Hopkins University.

DeCarlo believes we should proceed with caution — but take these results with a grain of salt, considering the methodology of the study.

“They said there were more droplets produced by the neck gaiter rather than by wearing no mask, but statistically there weren’t more, when you consider the error for measurement,” explains DeCarlo.

Essentially, this means that the findings of a neck gaiter being worse than a mask are not statistically significant. Statistically, the gaiter tested at about the same level as wearing no mask.

To DeCarlo’s point, we do need additional studies — as well as a more comprehensive review of particular fabrics and fits — in order to reach more conclusive results about varying types of gaiters and masks.

“There are lots of questions that remain in my mind from this study,” DeCarlo continues, “to focus on neck gaiters and not the fabric or fit, which we know to be very important, seems to be ignoring important variables.”

That’s also because, contrary to many outlets’ biggest takeaway from this study, testing masks in a robust way was not really the purpose of this study at all. The set-up and experiment was, as DeCarlo said, rudimentary — but it was that way on purpose.

You can see the photos of the masks that were tested, as well as the chart that outlines the findings here:

Masks for the prevention of COVID-19 as tested by Duke University School of Medicine. | Photo Credit: Emma Fischer, Duke University

Graph showing the results of testing of various masks for the prevention of COVID-19. | Courtesy of Duke University.

It’s generally not wise to jump at the first study that appears — particularly if it’s only one study. The credibility is there for this research, of course: Duke University is a strong research university, and Science Advances is a reputable peer-reviewed journal with a relatively high impact factor (a measurement of a journal’s reach and importance) of 13.116.

But, as mentioned above, the purpose of this study was not a comprehensive testing of mask efficiency — but rather, as its title says, a demonstration of a “Low-cost measurement of facemask efficacy.” In short, the aim was not to conclusively test the vast array of masks people have been using — but rather, a public service: a demonstration for businesses and non-experts of an easy, inexpensive (less than $200) method to determine, at least in a rudimentary way, if the masks they are making and selling are effective.

“We have demonstrated a simple optical measurement method to evaluate the efficacy of masks to reduce the transmission of respiratory droplets during regular speech,” the study’s abstract reads.

The neck gaiter finding, though alarming, is ancillary to the purpose of the study, which is why the testing they did was so limited. The majority of those black dots on the graph were just measurements from one person testing out one mask ten times in a row — the hollow dots are the average of four people testing out a mask ten times in a row.

That’s not a whole lot of research by any standard. Which is fine, because the study was just an example of how this testing process could be replicated, rather than a robust scientific process executed over time with a purpose to comprehensively test all market masks’ efficacy.

Nevertheless, Pegues thinks that though this is one study with limited testing, it’s calling enough attention to a potential problem that we should be changing our behaviors in response.

“The study findings, although performed in a laboratory setting and not while exercising, suggest that if you want to protect others, including your fellow runners, from COVID-19 infection, don’t wear a regular neck gaiter or fleece,” says Pegues, “Instead, wear a two-ply face mask.”

Just another day in the ever-evolving hellscape that is living through a pandemic. It’s a moving target, no?

But hey — science is fluid, and recommendations for what’s best for our health change constantly. That’s why there’s a scientific method — and why Thomas Edison said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” And, (as we’ve heard ad nauseam) these are unprecedented times — and there are bound to be ever-evolving changes and advances in our knowledge. As that happens, we’ll adapt, recalibrate, and move forward. If a new study comes out that proves a different type of mask or a specialized type of gaiter works better, we’re all for it — or, you can just replicate the Duke study and test it yourself.

For now, we’re acknowledging the points brought about by this (albeit limited) research, and recommending ditching your neck gaiters — particularly standard, thin gaiters — like these or these — for use as tools to prevent the transmission of COVID-19. (They’ll still work wonderfully for cold-weather running down the line.)

“Some fleece gaiters you can hold up and literally see through — and that means the air can go straight through, too,” says DeCarlo.

If you have a thicker, more high-tech running gaiter made of unique fabrics — like a Zensah Gaiter — it very likely is more effective, which could be confirmed after further testing. But, we’d still advise erring on the side of caution and eschewing the gaiter in favor of two-ply mask in public for now — especially if you’re indoors. (Here are some two-ply face masks to check out if you need to shop for a new one.)

If you’re still in doubt, just stretch out your neck gaiter or running buff and take a look. As DeCarlo noted: if you can see through it, air is moving through it — meaning it’s probably time to stop using it as a mask.

Want to hear more from us? Join Be Well Philly at:

FACEBOOK | INSTAGRAM | NEWSLETTER | TWITTER