Philly Colleges Plan to Return In-Person. Some Professors Aren’t So Sure.

Do professors feel comfortable returning to teach on campus this fall? That depends on whom you ask — the administration or the faculty.

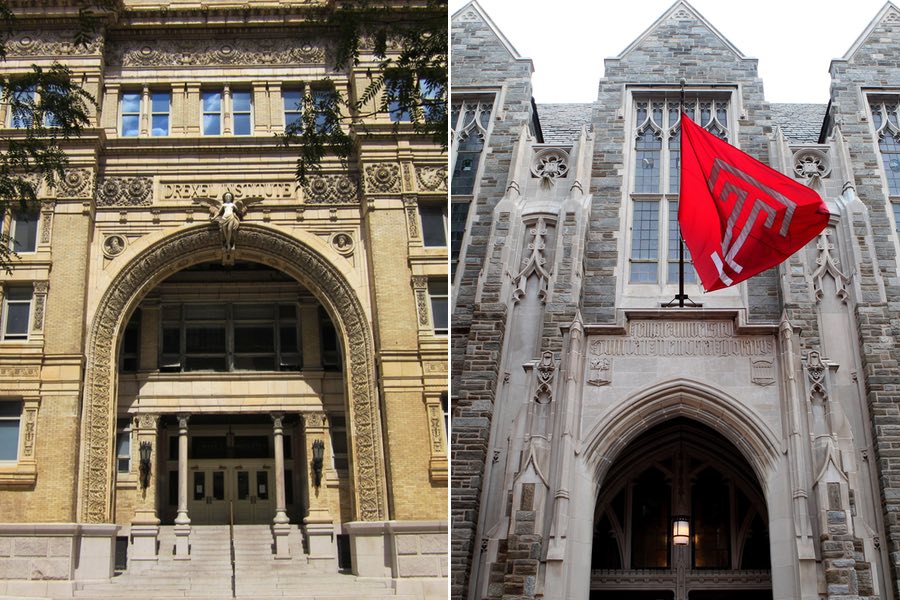

Drexel and Temple both have plans for college reopening this fall that involve in-person classes. Photos (left to right) by Ameykhanolkar/Wikimedia Commons and Raymond Boyd/Getty Images.

As the fall draws nearer, we’re finally starting to learn how education amid pandemic might play out at universities. Back in the spring, when the coronavirus first hit, there was near universal agreement among the country’s institutions of higher education: All classes would immediately pivot to online instruction. But now, even though the country is reporting more COVID-19 cases than at any point in the spring, schools are starting to express different philosophies. Some, like Harvard, are remaining entirely online. Others, like Temple and Drexel and Penn, are bringing students back to campus for a “hybrid” experience, in which large courses will take place online and smaller ones in person, at the discretion of individual departments and deans.

These distinctions aren’t as extreme as they initially might seem. Harvard, not forgetting the fact that a significant portion of its revenue comes from being a landlord, is still encouraging freshmen to come to campus (read: dormitories) in the name of some vague, idyllic “college experience,” though it will surely be more like a funhouse mirror version of college, with students holed up in dorm rooms, taking classes on the computer. Only in a few cases, like at Dickinson College, have institutions said they planned to close down dorms altogether and embrace a truly remote model.

So far in Philly proper, just one school has committed to completely online learning: The Community College of Philadelphia. (It also happens to be the one school that isn’t a landlord.) The others have all embraced hybrid learning to varying degrees. There is, of course, another reason for this. Colleges have been trying to simultaneously transform the way they operate, while convincing their students that nothing meaningful has changed — that if they return to campus, they’ll get the same quality education and the same suite of best-years-of-your-life experiences … for the same price.

But amid all of this shuffling, there’s another group at some schools that is starting to feel they weren’t adequately consulted during the process: the professors.

Battle of the Surveys

At Temple, Steve Newman, a professor of English and president of the Temple Association of University Professors (TAUP) faculty union, has numbers to back this up. A few weeks ago, he sent a survey to his membership — 2,700 faculty, adjuncts and librarians — asking that very question. Of the 360 to respond, 86 percent said they didn’t feel sufficiently included in the university’s decision-making. Seventy percent said they didn’t feel comfortable returning to campus. In a separate survey, Temple’s graduate student union polled its members and reported that 80 percent didn’t feel comfortable teaching in person, either. Newman says he has “grave concerns” over the process Temple has developed — not one of the members of the school’s “Return Team” task force represented the faculty or graduate student unions. Ray Betzner, a school spokesperson, said via email that the Temple faculty senate, which represents more instructors than TAUP, reviewed all of the school’s plans and that “its members are the appropriate voices to be heard when these decisions are made.”

Newman’s concerns aren’t just about the deliberative process — equally troubling to him is the end result. Professors who don’t wish to teach in person have to apply for “accommodations.” Newman believes the process is backwards: The university should have asked which professors would opt in to classroom teaching. “If they would’ve started there, they might have gotten enough people willing to teach on campus,” he says. That way, the school wouldn’t have needed to bother with the accommodation process in the first place. Simply put: Newman feels as though the university’s approach risks “forcing employees to choose between their lives and their livelihood. That is not a moral choice,” he says.

Temple administrators feel differently. Betzner wrote that the school has consulted with numerous faculty and staff and “has made it clear that it will work with every employee, including faculty members, to make sure that they are in a safe working environment.” Betzner also cited the university’s own surveys, which he said found that “89 percent of the faculty respondents agreed the university is managing this situation well.”

At Drexel, there is similar worry over process and results. David Kutzik, head of the school’s (non-unionized) chapter of the Association of University Professors (AUP), sent a survey — notice a trend? — to nearly 800 faculty across the institution. Five hundred responded, 77 percent of whom said they didn’t feel comfortable teaching in person. (Nearly half also said they considered themselves at high risk of experiencing serious side effects of COVID-19.)

Drexel also convened a COVID-19 task force, but almost all of the faculty represented there had dual roles as administrators. Rank and file faculty were virtually unrepresented. “We had no role on that task force,” said Kutzik, who spoke as if he were tiptoeing barefoot around glass. “It would have been helpful, perhaps, to be able to play a role in it.”

Much like at Temple, Drexel administrators say they had their own conflicting survey results. Interim provost Paul Jensen noted that a school survey, which had more than 1,200 responses, found the hybrid model was the most popular method for fall instruction. Still, Jensen wrote, “We are working with college, school and department leadership to ensure that no faculty member has to teach a class face-to-face if they are not comfortable doing so.”

The Budgetary Incentive

For all the supposed division between faculty and administration, the real divide isn’t over teaching. (“Of course we want to be in the room with our students,” says Newman.) It’s about money — and how much of a financial hit colleges can absorb due to the pandemic. Drexel is slashing its spending by $90 million; Temple has estimated it will lose $45 million. That is the concern of administrators, and it’s why so many are proposing a hybrid learning model that will bring as many rent-paying students back to campus as possible.

Drexel has more or less said this outright. In a recent email to staff, president John Fry mentioned that a prolonged period of remote learning would “significantly impact Drexel’s ability to continue to support our faculty and professional staff.” (Translation: Your jobs depend on Drexel having a functioning campus.) Jensen, the interim provost, says the message was simply meant to describe the financial toll the pandemic might have on the institution.

More than anything, this controversy is a way of understanding the inequality gap that exists, not unlike in society writ large, between the haves and the have-nots of higher ed. Plenty of analysts have already posited that the pandemic is going to hit the large middle class of schools — expensive, middle-tier residential colleges (e.g. Drexel and Temple) — hardest. The elite colleges will be fine. So, too, will commuter schools.

Maybe that explains why there’s been less chatter of faculty angst at some of Philly’s more elite colleges. Entire departments at Penn — even ones that have small class sizes — have already decided they won’t teach in person. Swarthmore has said all of its professors can opt out of in-person teaching, no questions asked. But for these schools, with life preservers in the form of their multi-billion-dollar endowments, the question of whether they’re able to tempt students back on campus isn’t quite as existential.

All of the universities promising a return to campus acknowledge they’ll have to be nimble. The fall terms won’t begin until late August, an eternity from now in pandemic time. But, as Temple psychology professor Laurence Steinberg recently wrote in a New York Times op-ed, there’s an even more fundamental reason — to say nothing of employee alienation — to be skeptical that the return to in-person teaching will go well. Steinberg, who has researched the brain chemistry of young people for more than 40 years, says they simply aren’t good at impulse control. It’s not even their own fault.

Steinberg’s prediction? “Many students will have become cavalier about wearing masks and sanitizing their hands,” he wrote. “They will ignore social distancing guidelines. … They will get drunk and hang out and hook up with people they don’t know well. And infections on campus — not only among students, but among the adults who come into contact with them — will begin to increase.” Steinberg, like Newman, says he’s requesting to teach this semester from home.