I Walked Across Philadelphia With a Record-Breaking Endurance Swimmer and About 50 of Her Friends

With the EverWalk initiative, Diana Nyad is trying to get more people to walk and talk. This is what one of her "Epic Walks" is like.

Endurance swimmer Diana Nyad and trainer Bonnie Stoll started EverWalk to get more people to, well, walk. / Photograph courtesy of EverWalk

Have you heard of Diana Nyad? I had heard of Diana Nyad. But when I received an email with the subject “Diana Nyad – interview opportunity / Philadelphia event,” remembering why I knew who she was was like trying to take a word on the tip of your tongue and spit it out into the world. Athlete, for sure. Swimmer, I think?

As I read farther down, my recall kicked in: Yes, she was the first person to swim from Cuba to Florida without some terrifying-sounding apparatus called a shark cage, which when I google it turns out to be a metal box that keeps you from being a great white’s next meal. She’d set or broken several other open-water swimming records — from Capri to Naples, across Lake Ontario, from the Bahamas to Florida — and subsequently worked as a journalist, an author, and a nationally renowned public speaker.

So why was she bringing a group of folks to Philadelphia to…walk?

It was the first question I asked when I got Nyad on the phone a few weeks before her 137-mile “Epic Walk” from Philly to Washington, D.C., the fourth in a series of 100-plus-mile walks that each take place over a week’s time. She was in the middle of a 10-mile practice walk while she talked to me, but that didn’t slow her down — her words came as quickly as I imagine her feet stepped, as if she wanted to break the record for conversational pace, too.

“When Bonnie and I finished the Cuba swim at long last (that was a unique endeavor; no one’s ever done it, and I’m not sure anybody will do it again, it’s truly of that sort of stature), but we were so high on the purpose of it and the team of it,” Nyad said in one breath. “We used to talk about swimming over the entire curvature of the earth and taking in this blue jewel of a planet as ours. As much as that would be tough physical stuff, you can’t help but start reflecting on what’s going to be the future of the earth’s oceans, what’s going to be the future of your life.”

“If you and I took a walk and looked up at the trees, the horizon, the sky, the blue jewel of the planet, sky instead of the sea, chances are we would come across deeper things than if we just chatted,” she continued. “Some of the great minds in history, from Steve Jobs to Thoreau to Charles Dickens, they walked to think. They walked to talk. Nietzsche was a big walker. They found that the endorphins of walking and being able to gaze far away at the horizon instead of being stopped by your screen where you’re only seeing six inches, 12 inches in front of you, is very freeing.”

At this point, I am utterly split. I can tell Nyad has told this same type of thing, this “let us see, really see, the curvature of the earth and use that as a vehicle to talk about meaningful things” line, to many people. This is the tagline, the calling card, the hook of EverWalk, this initiative to get people to walk that she started several years ago. I’m fully aware of this, and yet I’m also fully buying it. Nyad’s voice is hypnotizing but not in a lulling you to sleep sort of way. Rather, she draws on the second phase of the hypnotist’s act: With only a few words, she convinces you to do exactly what she says.

But it’s more than just her voice that makes EverWalk and its Epic Walks compelling. My theory is that Nyad has taken walking, an ordinary activity that few of us consider to be that life-changing, and made it cool. Sure, walking was on the scene already, thanks to FitBits and the whole 10,000-steps-a-day regimen. But there’s something different about an endurance athlete, who’s in the record books, who’s been on Saturday Night Live and profiled in the New Yorker, adding her endorsement to the practice.

For one thing, if you sign up to be even a daytripper on an Epic Walk (not everyone can afford to take a week off of work and pay for seven to eight nights’ worth of hotel stays just to walk), you can spend time with this world-famous celebrity. For another, Nyad is gamifying walking. On the Liberty Epic Walk from Philly to D.C., walkers’ mileage will be tracked via Runkeeper for the first time. And this fall, EverWalk is launching the 110.86 Mile Club; to become a “member,” you have to walk at least that distance in a month, which averages out to 3.4 miles a day.

Walkers on the Pacific Northwest Epic Walk in August 2018. / Photograph courtesy of EverWalk

And then there’s the charming elements, like the little plastic fireplace that the crew pulls out of the support truck at the end of the day on Epic Walks, so everyone can have a “fireside chat” about how the day went. “Some people have funny stories to say, but honestly, a lot of people come to reckonings,” Nyad tells me. “They come to peace. A lot of people our age [Nyad just turned 70], not usually millennials, are thinking about how much time is left, what do they want to do with their time, do they want to do more public service than they’ve been doing in their selfish, private lives? At the end of EverWalk, a lot of people say, ‘I’m going home with a new plan.’”

Well. I am a millennial. But I say there’s nothing like a quarter-life crisis to make you feel like you need a new plan. After half an hour or so on the phone with Nyad, I said I’d join these epic walkers for the first day in Philly.

And reader, EverWalk delivered.

***

The morning of August 26th was cloudy, the temperature in the high ’60s, and the group of about 50 EverWalkers gathered at the Independence Seaport Museum to start their Epic Walk were gleeful. Although most of them weren’t from Philly, they knew we and the rest of the East Coast had just come off a major heat wave that made even walking miserable. This, in contrast, was dream strolling weather.

It didn’t hurt that they got to stare up at Independence Hall and peek in at the Liberty Bell within the first mile. I felt like a local (and a bit of a know-it-all) as I regaled my fellow walkers with facts about the other Liberty Bell housed at Valley Forge. They were good sports, and the conversation flowed easily to how they got involved in EverWalk.

Michelle Pare had googled “inspiring women” and up popped Nyad’s name. Linda Stauf had been recruited by Laura Petersen, an early adopter in Los Angeles. That’s where Nyad and Bonnie Stoll, Nyad’s trainer and EverWalk co-founder, both live, and it was the starting point for their very first Epic Walk, which spanned 134 miles from Los Angeles to San Diego in October 2016. Petersen, a short, dark-haired, animated woman with enough energy to walk through a wall, had heard about this long walk and was intrigued, though, having never found a workout that worked for her, she wasn’t sure if it would take or whether she’d be able to make it through the whole trek. Turns out she loved the way walking lots of miles made her feel and, gradually, how it connected her to like-minded people. “I’m really enjoying this conversation,” she said as we walked toward City Hall, the forward-thinking William Penn keeping watch over us. “And if I weren’t doing this, I never would have met you.”

It hasn’t always been easy to convince new folks to join the movement, though, even with Nyad’s name attached. Petersen’s an official EverWalk ambassador and leads a shorter-than-an-Epic walk in the LA area on the first Saturday of every month, but the size of the group varies widely, and getting people to show up consistently has proved difficult. “Everyone’s so busy,” Petersen said. “They don’t want to commit to being at a certain place at a certain time.” The EverWalk Nation Facebook page, the communication hub of the group, counts close to 1,100 members, but there’s a handful who drive most of the conversation. That’s how it is with virtually every group (not everyone feels the need to be a vocal leader), but as we came out on the other side of City Hall, I pondered what it really takes to build a thriving community.

At this point, Petersen et al. made a pit stop for a restroom break, and I fell in with another small group. I was immediately drawn to Toria Price, a tall woman with short, silvery hair. There was a grace about her — both in her posture but also in her aura, like she understood her own self-worth. It took us no time at all to start talking about deep topics. As we walked past the Love statue, the concept of crossroads came up. For years, Price lived in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she ran a school and a prominent Native American art gallery, but when she was forced to move, she decided to become, essentially, a nomad. Now, as a paid public speaker and author, she travels across the country (and sometimes around the world) with her Subaru Crosstrek and her dog.

This sounds like a charmed life and, in a way, Price has led one. She’s the daughter of Vincent Price, who was well-known as a horror film actor and an art historian and collector, and has had access to wealth and connections that most of us will never get within six degrees of. Yet she said she’s always seen herself as a rebel, understood intimately and early that the life of the rich and famous wasn’t for her. At one point, she was an interior designer for the one percent but decided instead to go to seminary and become an interfaith minister. At another, she went to graduate school and studied the cult of celebrity, to better understand the world she’d grown up in and why people cared about it so much. “It was like therapy,” she told me.

I confided that I felt similarly, that I would rather tell the stories of the marginalized than the privileged. That I agonized about all the terrible things going on in the world and felt helpless to make an impact. That, over and over, I’d been told I didn’t fit into modern society and struggled to find people who recognized my value. That I felt alone most of the time.

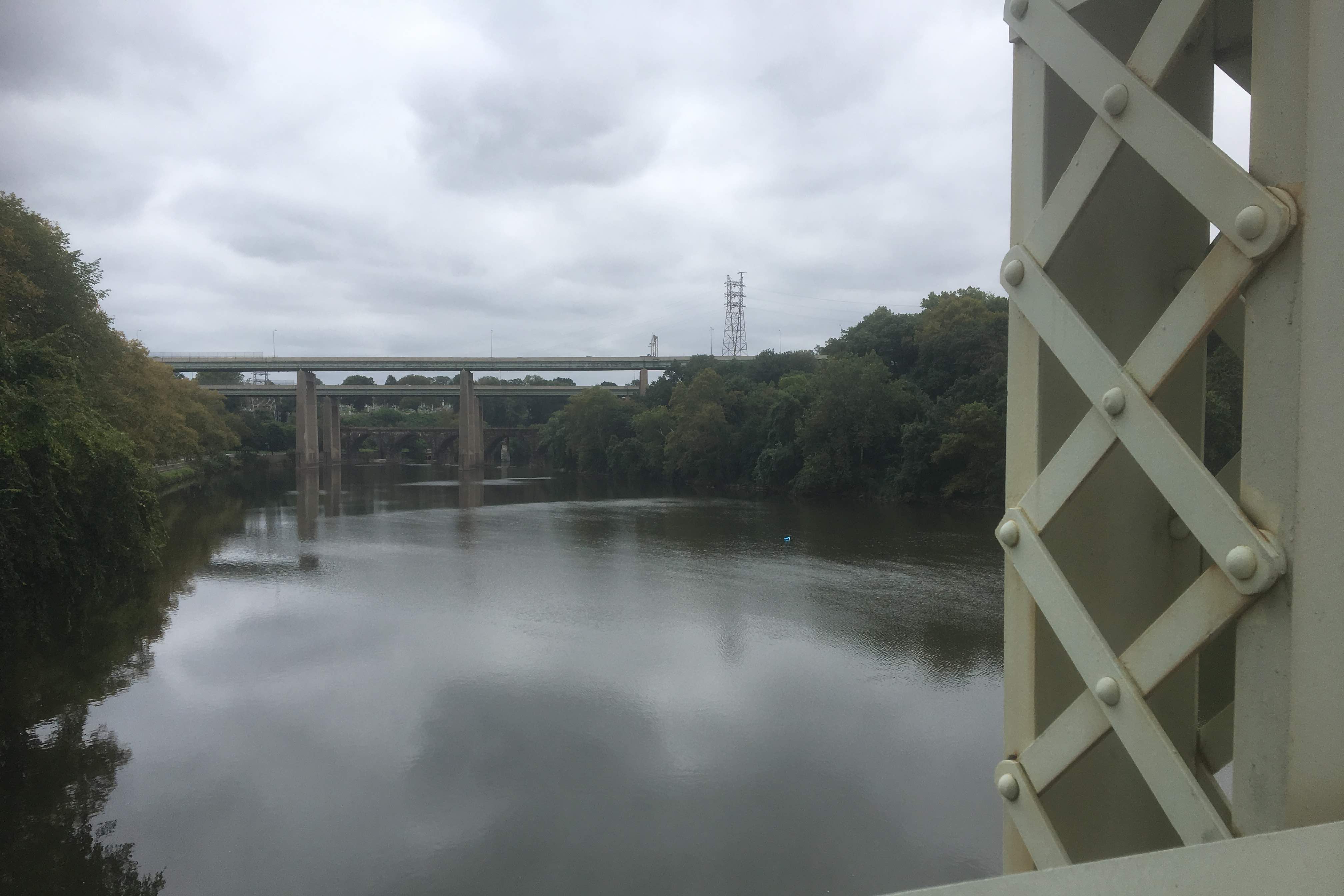

Now. I’m a fairly open person, to a fault sometimes. But I’ve never cracked open my heart and spilled its murkiest contents this quickly with a stranger, face to face. By then, we were crossing the Schuylkill River, and the water was stone gray, more of a mask than a mirror. The sun didn’t break through the clouds and shine a light that gave me hope or metaphorically showed me the path forward. But Price turned and looked directly at me. I’d mentioned to her that my chronic insomnia often prevented me from functioning like a coherent human. I, she said, was aware of the systemic problems and my own otherness and the tragedy of it all and the need to burn it all down, and that was power I could harness. “Maybe it’s not time for you to sleep,” she said. “Stay awake.”

Bridge and river sights on the Epic Walk. / Photographs by Mary Clare Fischer

***

Fast forward to the afternoon. We’d stopped briefly for lunch, where most people had taken off their shoes — my kind of humans — and then quickly headed back out on the trail. I ended up talking to Catharine Fitton, who headed up much of the recruiting for EverWalk. Much of her work was around finding ambassadors, like Petersen, who would lead walks on the first Saturday of every month in different locations. These weren’t Epics but shorter hikes that could grow the community beyond its fervent base. Folks were simply asked to post a picture of the walk on the Facebook group to create a sense of togetherness across the country.

She’d done a remarkable job, growing the program to about 60 ambassadors in maybe a month of work. One of those new recruits was Lisa Phillips, the Philadelphia ambassador, who’d be leading the first short group walk in Philly on September 7th. Although she was participating in the first day of the Epic, like me, I never ran into her, proof that the group was large enough to prevent you from talking to everyone, even on an all-day walk. (I wasn’t able to get in touch with her before this piece ran, but I vowed I’d try to experience her version of EverWalk.)

Walking back to Center City on the Epic Walk. / Photograph by Mary Clare Fischer

I detoured into a Barnes & Noble to use the bathroom and ran into Pare and Stauf, my first walking buddies, who’d had the same idea. I started chatting with Stauf, a thin redhead with a kind demeanor; she’d told me she lived in Louisville, Colorado — not too far from Denver, where I’d made my home for quite some time before moving to Philly. She asked about my job and background, and I told her my mother was a dietitian. Turns out Stauf had wanted to be a dietitian as well, but all the chemistry involved had scared her away. Instead, she got a degree in social work and later became a stay-at-home mom. At 50, she vowed that she wouldn’t let chemistry continue to get the best of her and enrolled in a lab at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Of course, she aced it.

But as we looped back into Center City, we talked more about me. Stauf always had another question and enough patience and interest to listen to the answer. In a way, it was unnerving; I’m used to asking the questions. For the millionth time that day, I felt heard. And I wondered again — what does it take to build community? Was it the star power of Nyad? Was it this walking format that caused typical social norms to fall away in favor of a more authentic way of living? Was it truly this group of passionate, honest people, who decided together to revel in the beauty of the curvature of the earth?

Our finish line for the day was Head House Square. I didn’t see the plastic campfire, but there were candles that made a little ring instead. The people who finished before us were already rubbing gels on their feet and munching on snacks; some grabbed ice cream from the shop across the street. Lights were strung across the ceiling above us, and a celebratory vibe hung in the air. And then Nyad began to speak.

Photograph by Mary Clare Fischer

Photograph by Mary Clare Fischer

She told the story of John B. Kelly Sr., the actress Grace Kelly’s father, whose bronze sculpture we’d passed along the Schuylkill. He grew up in East Falls and was one of the best scullers — a rower who uses two oars — in the state in the early half of the 20th century. As a top athlete in his sport, Nyad explained, he figured he’d be eligible for the Henley Royal Regatta, a premier rowing event in England. Yet he was denied permission to compete because he was a bricklayer, a working man, and Henley was reserved for the upper crust. Kelly was not dissuaded. He went to the 1920 Olympics, raced the winner of that year’s Henley, and beat him. Not by much, but it didn’t matter. The victory was his.

As a middle finger to the bourgeoisie, Kelly allegedly sent his sweaty cap to George V, the king of England at the time, and vowed that his unborn son would win Henley some day. Not only did that promise come true (John B. Kelly Jr. won twice at Henley), Nyad said, but the current queen of England still has that hat.

Throughout, Nyad’s voice soared and dipped, empathizing with the sting of rejection that Kelly had experienced at his lowest point and saluting him at his triumphant summit. Mesmerized, the rest of us fell and climbed with him and her. Today, we had conquered adversity. And tomorrow, we would walk on.

The first Philly Phriends EverWalk (not an Epic Walk) is Saturday, September 7th, starting at 8:30 a.m. at Boathouse Row’s Lloyd Hall. Register here.