The Senator Says He’s Not a Rapist

Daylin Leach’s accusers call him a monster. He calls their charges lies. Power, politics, and sex in the age of #MeToo.

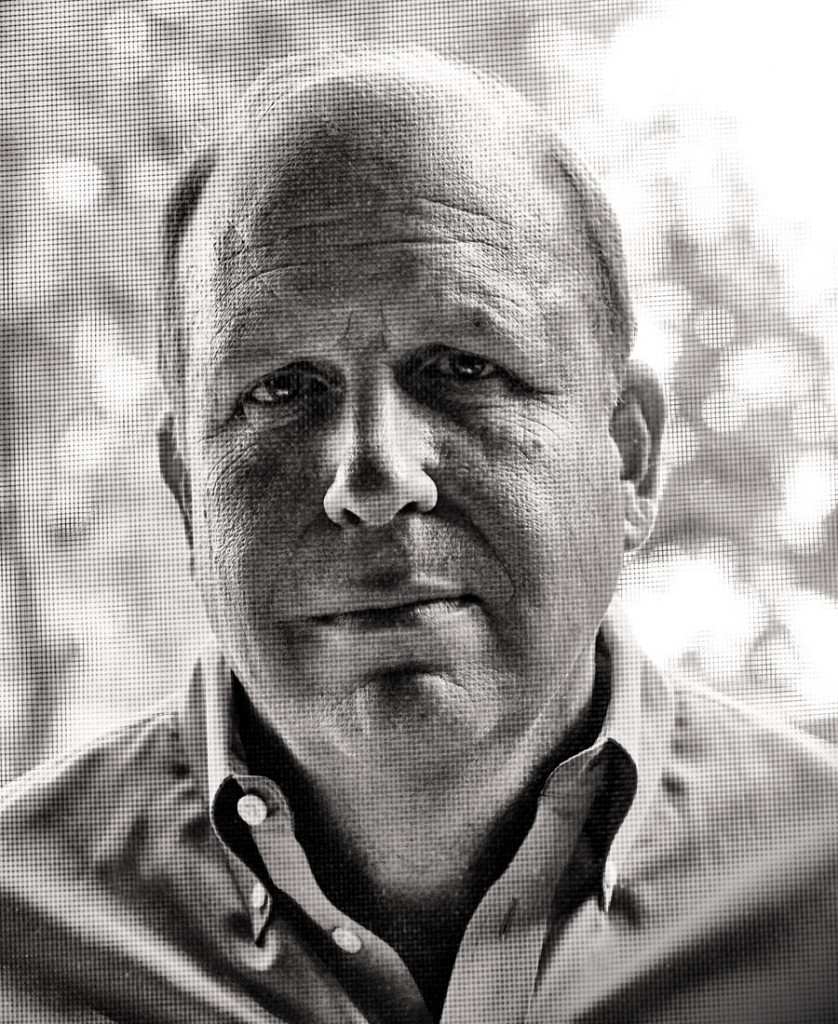

Pennsylvania State Senator Daylin Leach, photographed in July. Photograph by Dave Moser

This is the kind of thing that set it off.

Five years ago, Daylin Leach, a state senator from Wayne, was gearing up for a run for Congress. Leach is a magnetic guy, a former stand-up comic who pulls people to him; he was the cool boss in Harrisburg, fun to hang with. Leach was also a hard-charging progressive at a time when progressives were still in very short supply in the state Senate. He was the guy who made medical marijuana a reality in Pennsylvania. Who was at the forefront of gay marriage, who championed women’s issues. With a 10-foot basketball hoop in his big office off the Rotunda in the State Capitol.

She was young, in her mid-20s, and would occasionally stop by to chat politics. She had worked under Leach, though not directly for him, and had gotten to know the senator a bit. They’d talk — Leach is a big-league talker. One day she went to his office to kill some time — she still worked in the Capitol — and gossip a little. People often came in and out of his office.

Alone for a moment, they shot hoops. Leach is hulking and awkward, though a surprisingly good athlete, if shooting hoops in an office can be called athletic. They were chatting, firing set shots, and that’s when she says it happened: Leach’s hand was on her back and moved up and down. She ignored it. It was only a couple of moments, his hand on her. But it was a little … odd.

So she moved away — went to the couch along one wall and sat down. Leach followed and sat next to her — in fact, she says he sat so close on the long couch that their arms touched. He didn’t have to be so close. They were still alone; Leach kept talking. She doesn’t remember the conversation now, though it was budget season, so it was probably about that, or maybe someone’s upcoming campaign. What she will never forget is how he sat right there next to her, his arm touching hers, and now it wasn’t just a little odd but downright strange, and uncomfortable. She didn’t move away from the senator, or ask what he was doing, or ask him to move. She got up and left his office.

The woman, who asked that her name not be used, has shared that story with a dozen or more people over the years. When she considers, now, what it was about — those few minutes alone with Daylin Leach in his office — she doesn’t know.

Maybe it was a test. Maybe he was seeing what he might be able to get away with. Maybe he wanted to see what she might be willing to do. She doesn’t know.

When I tell Daylin Leach, in his backyard in Wayne on a hot Friday in July, what the woman claims happened in his office and how it made her feel, he says he doesn’t remember any such incident. This is how it’s gone since December 2017, when the Inquirer published a long front-page piece about his behavior with women who work with him. A pat on the knee, a hand on a shoulder, a dirty joke told maybe 10 years ago — “That’s what they’ve got?” he wonders, again and again. He describes himself as a guy who touches people, says his hand on a knee or an arm or a back is simply part of his natural energy and friendliness. The accusations strike him as small and absurd.

Others have had a different reaction, starting in late 2017. Al Franken had just resigned from the U.S. Senate over his behavior with women, and the Harvey Weinstein story had broken in October. The day the Inquirer article appeared, Governor Tom Wolf called on Leach, a fellow Democrat, to resign. Leach was in the midst of a second run for Congress, and his campaign staff descended on his house in Wayne en masse to quit. His Senate staff urged contrition, but Leach isn’t built that way. Instead, he lashed out online, calling one accuser “a truly horrific monster” and “a human wrecking ball of hate.”

It would get worse.

Early this year, a woman named Cara Taylor would go to Harrisburg and pass out to each state senator a copy of a criminal complaint. It claimed that in 1991, when she was the 17-year-old daughter of a woman whom Leach, then a 30-year-old lawyer in Allentown, was representing, he manipulated her into performing oral sex on him in his apartment. Though the complaint was unsigned by Taylor and the alleged crime was far beyond the statute of limitations, Leach’s caucus, the Democrats, hired a law firm to investigate.

Cara Taylor, photographed in early August. Photograph by Dave Moser

But instead of slinking off, à la Franken or Charlie Rose or Matt Lauer or other public figures either fired or shamed into quitting, Leach again doubled down, characterizing Taylor as a convicted perjurer who has changed her story multiple times, and suing her, along with two #MeToo activists who have called him a rapist, for defamation. He’s now preparing a lawsuit against the Inquirer to boot.

Certainly, Leach’s career is at risk — though it’s not just his career; this is also a judgment of just what sort of man he is. “I can’t let these fuckers win,” he says in his Harrisburg office in late June, meaning his most adamant accusers. “Is that the protocol now? Someone says something about you and we just assume it’s true? And you have to go, you’re gone. Shunned from the community.”

The stakes really go even deeper than that. The Leach case has Democrats fighting in Montgomery County and in the state Senate over Old Boy loyalty and power, as a new day for women in the workplace — and in power — comes fitfully forward.

“Is that the protocol now?” Leach asks. “Someone says something about you and we just assume it’s true? And you have to go, you’re gone. Shunned from the community.”

The Senate broke for summer recess just after a bizarre showdown — with progressive women leading the charge — over Daylin Leach. Expect more fireworks this fall, because they’re just getting started. It really is a brand-new day.

Not so long ago, he was riding high.

Victoria Cox, like a lot of progressive Democrats, was woefully depressed after the 2016 presidential election, and she credits Daylin Leach for bringing her out of her funk. Leach emceed a “resistance forum” at an Upper Merion school just before the inauguration of President Trump, and Cox, then a committeeperson in Montgomery County, was taken with his passion and candor and wit. Afterward, she went up to him, “and he very gently put his hand on my forearm and said, ‘You’re not alone,’” she says. Which was exactly what Cox needed. Other progressives talk about a similar effect Leach has had on them, and what he’s been delivering as practically the lone arch-progressive voice in the state House and Senate for almost two decades. Leach certainly walked the talk: As a state senator, he has pushed not only the legalization of medical marijuana, but also bumping up the minimum wage, extending anti-discrimination protections to Pennsylvania’s LGBT community, and banning the shackling of pregnant prisoners. He has aggressively opposed measures that seek to curtail women’s rights, including a bill in 2017 that would have banned abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

In the summer of 2017, at the Radnor Hotel, Leach announced his candidacy for U.S. Congress in the 7th District, citing the need to take on Republican incumbent Pat Meehan in the age of Trump. It looked like his race to win.

Then, that summer, Inquirer reporters Angela Couloumbis and David Gambacorta came calling. Couloumbis works out of Harrisburg, Gambacorta (who once worked for Philly Mag) is in Philly, and they independently started getting leads about Daylin Leach. The reporters began calling his ex-staffers and campaign workers, asking about Leach’s behavior with women and the atmosphere in his office.

In mid-December 2017, the Sunday Inquirer ran the long front-page article. It began with the story of a 27-year-old woman named Emily who in early 2016 was a temporary employee of the Senate Democratic Campaign Committee, which Leach then chaired. She met Leach at a fundraiser in Harrisburg one night, and the next morning, while she was registering guests for an SDCC breakfast in the Hilton, Leach sat next to her, she said. Emily was wearing a skirt, and as Leach chatted her up about his advocacy for women and told her he might be able to find her a job, “He grabbed my thigh, almost to punctuate his point with a cruel irony,” she told the paper.

Aubrey Montgomery, the finance director for Leach’s 2008 Senate campaign, was the only critical source who went on the record in the Inquirer article. She acknowledged that Leach pushed policies that helped women. “But as great as his legislative record is for women globally, he can be awful to women individually,” Montgomery said. The Inquirer noted that “eight women and three men recounted instances when Leach either put his hands on women or steered conversations with young female subordinates into sexual territory, leaving them feeling upset and powerless to stop the behavior.” Examples of sexualized banter the Inquirer cited: Leach would talk about “actresses he wanted to sleep with” and how he wanted a “full set” of secretaries that would include a blonde, a redhead, a brunette and a “bald chick.”

After the story was published, Leach wrote a long Facebook post in which he denied incidents in the article and decried the “whisper campaign” that had been started against him. One day later, though, with media coverage of the story raging on and calls for his resignation mounting, Leach took to Facebook again to announce his intent to “step back” from his Congressional campaign. He also offered the following statement: “While I’ve always been a gregarious person, it’s heartbreaking to me that I have put someone in a position that made them feel uncomfortable or disrespected. In the future I will take more care in my words and my actions.”

The effective end of Leach’s Congressional run wasn’t the only fallout from the Inquirer story. One of the people who read the piece was Cara Taylor, who immediately called reporter Angela Couloumbis. By February, Taylor was making her own allegations about Leach on social media. In response to a Leach tweet that said President Trump was “ripping families apart” with his position on DACA, Taylor posted:

Replying to @daylinleach

Ripping families apart? Remember when you ripped mine apart? Do you remember when you sexually violated me and then sentenced me to a life of poverty when you conspired to have me convicted of perjury so no one would ever believe me? If Im lying then SUE ME.

Around the same time, Taylor began communicating with a group of women whose goal was clear: to hold Daylin Leach accountable for his behavior.

One of the women was Colleen Kennedy, a political operative who’d worked for Leach during his first Congressional run in 2013 and come to see his office environment as toxic. Kennedy had sent an email to Ronan Farrow, the New Yorker reporter who helped break the Harvey Weinstein story. In it, Kennedy described herself as a “silence breaker” and “the leading whistle-blower” against Leach. (She was reaching out to Farrow in hopes he would write about Cara Taylor.) “He is a monster,” Kennedy wrote of Leach, “and he is more vindictive and invincible than anyone could imagine.”

In their online communication — including an anti-Leach Facebook group they formed called Project Puke Fuck — the women offered support and advice to one another. Early on, after first hearing Taylor’s story, Kennedy wrote to her: “I tend to believe women. this stuff is ruthless though so it’s always safer to figure it all out before you come forward and know what questions will be asked and just be ready for it. … I’m really sorry for all that you’ve had to deal with, and please hear this from me … you have no one to apologize to.” Her appraisal of Leach was unwavering: “We need to take away his law license,” she’d write to Taylor later in 2018. “He’s dog shit.”

Kennedy, by her own admission, had once revered Leach online as a progressive hero, won over when she was still a college student taking in what she called his “amazing, thoughtful arguments.” But Kennedy would come to revel instead in the confrontation: “I … ran into a daylin defender who refused to shake my hand,” she messaged Taylor early this year. “I’m enjoying making them all feel uncomfortable.”

“You are seriously a fucking BEAST,” Taylor replied. “I wish I could be a fly on the wall … just to watch Batman in action … fuck, it gives me goosebumps.”

Gwen Snyder, an activist who was also part of the group, took up the fight with a vengeance as well. “I’m a sexual misconduct accountability trophy hunter these days,” she wrote. She had a place on her wall “reserved for Daylin’s [head], and plenty of space left over for more.”

Daylin Leach in 2013, announcing his intention to introduce a bill legalizing same-sex marriage in Pennsylvania. Photograph by Matt Rourke/Associated Press

When it comes to the forces aligned against him, Leach is angry, certainly, but he also seems confused. Early on in our conversations about all this, he admitted something in passing: “I’m almost oblivious to the emotions of others.”

His surprise over women’s reactions to him might explain why he’s tended to lash out at accusers. Last summer, after then-candidate (and now state senator) Katie Muth refused to share the stage with Leach, he sent an email to Montgomery County party head Joe Foster calling Muth, who’s a rape survivor, “a dreadful person” and “a toxic hand grenade.”

The woman who says Leach made her uncomfortable five years ago in his office in Harrisburg as they were shooting hoops has a subtler take on his anger now: “I feel like Daylin generally, he knew where the line was, he knew how close he could get to not really trigger any accusation of something inappropriate. If it weren’t the middle of #MeToo, his behavior wouldn’t be taken seriously. I think that’s why he’s so angry, because he never crossed the line to get in trouble. I’m just a touchy-feely guy.”

There’s no question that #MeToo has charged the atmosphere, emboldening women who might otherwise have remained silent. At a Leach fund-raiser at the Great American Pub in Conshohocken in June of last year, Cara Taylor, Gwen Snyder and a few others demonstrated and chanted. Taylor’s sign read:

I was 17 when Daylin Leach planned and executed my SEXUAL ASSAULT. Was he joking then, too?

Leach’s daughter, Brennan, came outside and started screaming at the demonstrators. “Do you know who I am?” Taylor said to her.

A Leach staffer put a hand up, walling off Brennan and ending the moment.

“She was the same age I was when her father did what he did to me,” Taylor says now. Seventeen.

In an op-ed that Daylin Leach wrote for the Inquirer three weeks after its article ran, he was clearly searching for understanding: “I spent my childhood in profoundly uncomfortable situations. I had very limited parental contact, no siblings, and lived in a series of challenging foster homes. I learned early on that humor and personal contact were ways to make friends and put people at ease.”

Leach never met his father. “You know how some people have annoying habits,” he says in his office in Harrisburg during budget week in late June, “like leaving the toothpaste top off? My dad had the annoying habit of impregnating women and then changing his name so he didn’t have to pay child support.” “Leach,” in fact, was a name his father had borrowed from a long-deceased aunt. And Daylin’s mother — young, naive, a graphic artist — was a reluctant parent as well.

“It’s hard to talk about your mother this way,” Leach says. “But she was ill-equipped to be a parent, especially a single parent of a hyperactive kid with ADD. I now know I have a wicked case of it. When I was four or five, she told me there were mothers who love their sons much more than she did and that she was going to give me away.”

She did. Leach lived in a series of foster homes from ages seven to 11, and his description of life in those places is nothing short of nightmarish. At his first placement, Leach says, he accidentally broke a window, and his foster father later asked him for one reason why he should let him live. He told Daylin he was going to kill him and had him record a last statement before taking him out to Ivy Hill Cemetery, just behind their backyard in Chestnut Hill. Daylin started screaming, and the threat of violence stopped there.

A couple of foster homes later, in Northeast Philly, nine-year-old Daylin shared a room with two other foster kids: another boy, who was 13, and a girl who was five or six and still not potty-trained; she spent all her time in a crib. Leach says dinner was often a boiled potato served in the water it was cooked in, as if it were soup. “My wife thinks that may be why I have food issues now,” he says. “I order at restaurants as if I think I’m never going to eat again.” Leach says that one night when the other boy came home, he said to Daylin, “Check this out.” He then proceeded to have the girl suck his penis, which Leach says happened multiple times. He wanted Daylin to do it, too; he declined.

Mostly, Daylin stayed away from the house. Weekends, he would shoplift tennis balls and roam — if you had a ball, you could make friends with random people, invent some game. And he discovered books. One day, wandering Northeast Philly, he ventured into a library, where it was warm. He remembered his mom talking about Robert Kennedy on the day he was assassinated in 1968, when Daylin was six. Now he found a book on RFK, and then others on the Kennedys. He started reading about 19th-century presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester A. Arthur and devouring Time magazines, and he was off, suddenly intrigued by leaders and politics and what was happening in the world in a way that he wasn’t interested in anything at school.

After a year or so, his Northeast foster family had had enough of Daylin. His mother grudgingly took him back, though she’d send him off to boarding schools: first the George School in Newtown, where he got a free ride because his test scores were so high, then Church Farm School in Exton, with, Leach says, “troubled fatherless boys.” Mostly, Daylin stayed stoned on weed supplied by fellow live-ins from Philly.

Leach would study poli-sci at Temple, go to law school in Houston, and then head for Allentown, where he’d ended up with his mother, to practice law and enter local politics. And he started performing as a stand-up comic — he’d discovered he was funny back in sixth grade, and it quickly became a way to deflect trouble and get attention. He says now that “my favorite thing is to get a roomful of people laughing.”

As a newly elected state rep, Leach had an early dustup with the Inquirer in ’05 over his bawdy comedy. He was married and living in Wayne by then, with two young children. The page-one piece in the paper found his online comedic blog unbecoming to his position.

Leach hosted the Gridiron, the annual Harrisburg send-up of state politicians, for nine years. It comes naturally to him: “I struggle all day to keep my comedy in, because my brain just throws up stuff.”

Once Cara Taylor’s voice popped up online in early 2018, how Leach was generally viewed began to change. If he was capable of doing what she was accusing him of, then what everyone else was saying shifted from hard-to-pin-down accusations to something that seemed more sinister.

Back in the summer of 1991, Taylor’s mother, Kathleen Speth, was out of jail on bail. She’d been charged with the attempted murder of her husband, Cara’s stepfather — with running a hose from their car’s exhaust pipe into the house to asphyxiate him. Cara had picked Daylin Leach out of the Allentown phone book a year or so earlier for help in a minor landlord dispute; he was now her mother’s lawyer, and one day, Kathleen woke Cara late in the morning — Cara generally slept late because she often worked until 2 or 3 a.m. at a bar as a stripper. Leach was coming over to pick up Cara, who was 17 years old, to consult about the case.

She sees this now as a setup: Her mother offered her to Daylin Leach as a sort of payment, she believes, and perhaps for another reason as well, which we’ll get to.

At a lawyer’s office in Norristown one afternoon in late June, Taylor tells a wrenching story about that encounter. Leach told her, she says, that he wanted to take her to his apartment across the city because he had something to show her. Once they got there, she sat on the couch, looking around as Leach got something to drink from his refrigerator. The place was small and messy, with dirty clothes everywhere. It smelled.

“He disappeared behind me,” Taylor remembers. “After a couple of minutes, he called my name, and I got up to where I heard him, and it was his bedroom. I was standing in the doorway, staring at him — he was completely naked except for socks; his dick was hard and in his hand, and he told me to come help him out.”

Did it seem like a demand?

“It felt like that was exactly what I was there to do. I’m standing there, and every thought went through my head like in a movie, and my first thought was, I could leave. The front door was right there. By the time it took him to get dressed, I knew I could be up on Tilghman Street. I probably didn’t even have to run.

“Then all the other thoughts came. I didn’t have my purse. I didn’t even have a quarter. There were no cell phones back then. I knew that on Tilghman Street or the highway, either one, he could just find me. Without a quarter, how could I call Mom to come get me? Then I remembered if I got ahold of Mom, that would be the worst.”

Why?

“Because if I pissed off Daylin, then that would be it, she wouldn’t have a lawyer. … But I just — I knew I couldn’t make him angry. I knew that if I didn’t do what I was supposed to do, our lives were just over. … She was looking at decades in jail, so if I didn’t do it, I was ruining this — it was all ruined. … I remember thinking: Three, four, five minutes tops, and if I do a really good job, it won’t take long.”

Taylor says she knelt on the bed between Leach’s legs. He applied a red lubricant to his penis. She performed oral sex on him, and the lubricant tasted like berries and plastic.

Then he drove her home.

Taylor, 45 years old now, with four grandchildren, believes that Daylin Leach raped her that day 28 years ago. Forcible compulsion can be psychological as much as physical, she says: “People can be given choices without really having a choice.” Through much of her story, she’s been crying; now Taylor wipes her eyes. “I do it to my grandson: You can take a bath or go to bed.” She smiles. “He’s got to pick one.”

Daylin Leach says this episode with Cara Taylor never happened — that he never so much as even shook her hand.

Moreover, he says she’s not to be believed because she has a history of lying. Taylor would end up pleading guilty to perjury following the trial of her mother, who was convicted of attempted murder and served 10 years in prison. Taylor claimed at her mother’s trial that she was the one who ran the hose carrying exhaust fumes into the house — that she, not her mother, tried to kill her stepfather. It was a way out for her mother — an explanation Daylin Leach suggested, Taylor claims, that might save her mother from years in prison. She’s careful not to say that Leach told her to lie on the stand — he presented it to her as a possibility, something to consider, to create reasonable doubt about her mother’s guilt. And he said that prosecutors would go much easier on someone her age, since she was still a minor. Taylor says she took the bait and ran with it and ended up spending a month in prison herself, with a felony conviction yoked to her for the rest of her life.

“It’s about a power trip,” Taylor says of Leach. “It’s that I want something from you, and I’m going to take it. It could be sex, money, a car, a law — it doesn’t matter. It’s a personality. People like him need to be feared.”

Daylin Leach says he never suggested any such ruse to Cara Taylor — that she came to him claiming she had tried to kill her stepfather. He didn’t believe her, he says, and he told her to hire her own lawyer. His duty was to his client, Cara’s mother — to give her the best possible defense. The idea that Cara was a child who deserved better is absurd to him now: “It was not my job to nurture this girl.” He laughs. “And I wasn’t mentoring material when I was in my 20s.”

Which goes to the heart of what Cara Taylor is saying. Everyone — her mother, the criminal justice system, Daylin Leach — was only too ready to use her and then toss her aside. But she’s no longer willing to accept that that’s the way things should be. Those days are over.

“Daylin Leach,” she says, “ruined my entire life for a fucking orgasm.”

Though when you get down to it, she says, this isn’t about sexual assault: “It’s about a power trip. It’s that I want something from you, and I’m going to take it. It could be sex, money, a car, a law — it doesn’t matter. It’s a personality. People like him need to be feared.”

What we are witnessing through the #MeToo movement is a shift in power, brought into our state’s politics by Cara Taylor and Colleen Kennedy and Senator Katie Muth and others, and the fear that that power is generating.

In January of this year, Cara Taylor made the trek to Harrisburg to distribute her unsigned criminal complaint to senators. Her lawyer laughs about Taylor’s gambit now — how naive and bold it was of Taylor, and how effective it turned out to be.

That same month, Muth, newly elected, called for Leach’s expulsion. What bothers her most about his behavior, she says, is “his reaction to those allegations. We don’t talk about that nearly enough. He mocked victims on social media. I don’t care what’s true and what’s not true — it’s irrelevant compared to his reaction, and that has been cut out of the story repetitively. No reporter, no one in the caucus, is talking about that except me, and now [fellow senator] Maria Collett, and that is just mind-blowing to me.”

Both Muth and Collett are survivors of sexual assault. Leach calling Muth “a toxic hand grenade” has been much derided; when Collett tweeted her excitement over being named Democratic chairwoman of the Senate Committee on Aging and Youth, Leach tweeted: “Well, I’m very old. Though I look very young. So you’ll be serving me in everything you do.” (Leach claims that his Twitter account was hacked, and he hired an IT firm to investigate.)

It was enough to push the Senate Democratic caucus — not a body known to police its own — to hire the law firm of Eckert Seamans to investigate Leach, ostensibly over Taylor’s complaint, but in reality over any untoward behavior.

Meanwhile, Marcel Groen, the head of the state’s Democratic Party when the initial Leach allegations hit in 2017, had been pushed out by Governor Wolf a few months later — Wolf said Groen “embarrassed” him by refusing to back his call for Leach to resign. And trouble had been building locally in Montgomery County. This past February, at the county’s convention to endorse this year’s candidates, Senator Muth, whose district includes part of Montco, stood up and screamed that the party had to do something about Leach: “This is fucking bullshit!”

A month later, party chair Joe Foster presided over a meeting of Montco Dems at which they were pressed to sign a letter demanding that Leach resign. As the discussion went on, the mood became intense: If you don’t sign, it will look like you don’t care about women. Victoria Cox, now a political leader in the county and still a Leach supporter, was hugely disappointed as almost everyone fell in line, agreeing to sign the letter despite all Leach had done for them, and for the progressive cause, over practically two decades in office. “No one seemed to have any backbone,” she says. “It was like Agatha Christie: And then there were none.”

For his part, Daylin Leach filed his lawsuit for defamation against Cara Taylor, along with Colleen Kennedy and Gwen Snyder, in late January. Yet Kennedy and Snyder remain as adamant as Taylor. “We will not be silenced,” they say in a joint statement through their lawyers. “Daylin Leach is attempting to stifle and punish his critics through this lawsuit. These are behaviors unbecoming of an elected official. Senator Leach’s lawsuit appears designed to intimidate not only us but other potential witnesses.” Leach was putting the final touches on his lawsuit against the Inquirer this summer. “We’re going to own the Inquirer,” he brags, though what Leach wants, more than anything, is a page-one retraction that will take away at least some of the damage done by that first article two years ago.

At the heart of Leach’s suit against the Inquirer is an allegation that the paper went far outside the bounds of reasonable journalism in its reporting. Specifically, Leach charges that after Inquirer editors decided not to run an Angela Couloumbis story about Cara Taylor for fear of a defamation suit, Couloumbis crossed the line from reporter to advocate by coaching Taylor on what she needed to do to make her allegations against Leach part of the public record and thereby lessen the legal risk. Leach cites several posts written by Taylor on Project Puke Fuck as evidence:

1/16/19, 9:02 pm — As soon as I file for a pardon [for her perjury conviction] Angela says it’s a legal document that is public record and she can use that to report the story

1/16/19, 9:02 pm — There is NO way to answer the pardon application questions without involving Daylin. The who [sic] point of me filing that is for Angela’s ability to print the story

A week and a half later, after the paper still hadn’t run a story, Taylor wrote:

1/25/19, 12:30 pm — FUCK THE PARDON. I was only doing that so Angela would have a public document to publish her story.

Couloumbis disputes Leach’s analysis of her reporting: “If there’s any suggestion that I was somehow a Svengalian figure or master puppeteer pulling strings in the background,” she says, “it’s simply not true.”

Cara Taylor’s story is still the one that, for obvious reasons, carries the most potential trouble for Leach. Will it emerge from the stalemate of she said/he said? A friend of hers named Paulette Brown verifies that Taylor told her about the incident in Leach’s apartment not long after it happened. And then there’s the childhood friend of Leach’s named Jim Fike.

Fike, who’s now a hardware salesman in Florida, got wind of all this when a friend sent him the Inquirer article from late 2017. He then found Cara Taylor online. Fike met Leach when both were teenagers living in the Trexler Park Apartments in Allentown, after Leach’s mother took him back from foster care. They’d hang out, play ball, roam the city, and remained friendly through their 20s, Fike says. In 1991, Leach called him one day wanting to discuss something. Leach picked him up, and they ended up driving to a diner in New Jersey, where Leach told him about this impossible client he had who was charged with attempting to murder her husband by running car exhaust fumes inside their house. Leach kvetched about how he had no defense, that he didn’t know what he was going to do. And Leach shared one more thing, Fike says: “Jim, you’re not going to believe this, but I’m having sex with her daughter.” Cara Taylor.

Leach continues to deny any such thing ever occurred and says the conversation with Fike never happened. He trashes Fike as a right-wing conspiracy theorist whom he would never confide in about anything. And Taylor, Leach contends, has changed her story a few times. In 1993, her mother filed a complaint with the state Disciplinary Board, which oversees attorney conduct, that contained a statement ostensibly written by Taylor claiming she had a year-long affair with Leach and that he encouraged her to lie on the witness stand. Taylor says now that her mother wrote that statement, that it’s a fabrication, and that she was unaware of it at the time. (The board ruled that the complaint lacked sufficient independent evidence.) In 1999, in a different proceeding, Leach said under oath that he never had a sexual relationship with Taylor or suborned her perjury.

Leach also says that Angela Couloumbis told him Taylor changed her story during their interviews — that Taylor admitted the alleged sex was consensual, intended to finagle a lower fee from Leach for defending her mother, and that it was Taylor’s idea to lie on the witness stand. Asked about that in June, Taylor says Couloumbis misunderstood her characterization of the assault and that Couloumbis ended up apologizing to Taylor for her confusion. Couloumbis declines to clear things up now: “I don’t think it’s appropriate to talk about any reporting in this case or any other that never resulted in a story,” she says.

All of which proves nothing, except how hard it is to make final sense of a three-decades-old claim of … what? Cara Taylor says she was raped by Daylin Leach. Certainly, if her story is true, and a 30-year-old Leach coerced oral sex from a client’s 17-year-old daughter, who would then get up on the witness stand and attempt to take the rap for her mother, he behaved horribly, and it’s easy to say why that man shouldn’t serve in the state Senate.

But we don’t know — and we may never know — if Daylin Leach is that man. Though Leach is leaving no stone unturned as he hammers away at the story Cara Taylor tells of that day in his apartment: He says there was not, as she has asserted, a black leather couch or a huge piece of gym equipment in his living room. (He has pictures.) Nor is it credible, Leach says, that Taylor claims she was able to kneel on his bed, because in 1991, he had a water bed.

Regardless, Taylor’s accusation has given ballast to the more recent stories about him as a boss and how staffers have been made uncomfortable by his racy jokes and the way he touches them. These stories are important, certainly. But judging his office behavior has become difficult, and maybe impossible, since it is now colored by the worst possible reading of just who Daylin Leach is.

The state Senate doesn’t have a good history of dealing with sexual harassment allegations (or worse), and that history includes an earlier incident involving Daylin Leach. His caucus fielded a complaint in 2015 from a woman in her early 20s who said she’d had two run-ins with him, the first when she was an outside vendor hired by the Senate for events and the second after she’d become a staffer. The first incident: Leach allegedly went up to her at an event, put his hand on her back, and slid it down to touch her butt. The second: Several months later, she was working the front desk in a Senate office when, she claimed, Leach came in, went behind her, and tickled her. A member of Senate minority leader Jay Costa’s staff went to Leach and told him to stay away from the woman and to never do anything like that again. Leach angrily denied that it had happened at all, and that was that.

But suddenly, things have changed — the sort of change that seems to happen very fast but takes forever to get to.

Senator Katie Muth went ballistic, by her own assessment, in late June when her caucus met to discuss the preliminary findings of the commissioned report by Eckert Seamans. (Leach wasn’t present.) Eckert found no evidence of sexual harassment by Leach; no caucus rules had been broken. The summation found that “certain factual inconsistencies in [Cara] Taylor’s recollection of events exists” and also that “Ms. Taylor steadfastly believed her account of what transpired — her testimony on this point was detailed and passionate.” The report noted that determining the truth of her allegations would require a proceeding in which the principals were under oath, which was beyond the caucus’s purview.

This wasn’t what Muth was looking for. What really set her off was how there was almost nothing in the report about her experience of having to serve in the Senate with Daylin Leach. Or Senator Maria Collett’s experience, either. Both women, as survivors of sexual assault, find the very presence of Leach in the Senate — the way that makes them feel — to be beyond the pale.

“He’s not my rapist,” Muth says. “But we have to come to work, come in a room where people literally sympathize with the rapist, who might not have been ours. That is incredibly draining.

“To me, it’s the bullying situation, it’s not the sexual harassment. He’s a bully, and to this day, he still is. Maria and I have been in the Senate, we worked our asses off to get there, we have to sit with this guy, and everyone thinks it’s fucking normal. It’s not fucking normal.”

Muth says the Eckert lawyer told the caucus that the experience of the two senators was left out because the report was just supposed to be about previous work experiences, and that Muth and Collett came forward voluntarily to be interviewed.

“That’s when I lost my shit,” Muth says. “I said, ‘You’re a fucking liar.’” Eckert pursued her, she says: “I drove to Harrisburg on a non-session day, was interviewed for two hours, and they gave us three sentences in the report. I started crying — you never want to cry, but it was so frustrating. I took the time to say it all and was completely dismissed. That’s what a lot of caucus members realized. Maria cried, too.”

A few days later, when Jay Costa gathered the caucus around the lectern on the floor of the Senate, Leach suddenly showed up — seeming to come out of nowhere — and stood so close, twitching and hovering behind Muth and Collett, that they felt threatened. Muth looked at Collett next to her, and Collett’s lip was quivering. Muth led her to a side room, to drink a Coke Zero and calm down.

“It feels like waves crashing on us every day,” Maria Collett says of serving in the Senate with Daylin Leach. “It feels like needing to stand tall enough to get a deep breath. That’s how it feels.” One day, after a particularly uncomfortable moment during a Senate session, Collett texted Muth: “I feel like I’m 14 again, and I’m the slut and no one believes me.”

To Daylin Leach, Muth’s and Collett’s reactions to him are an absurd overreach: “Muth has an intensity of hate toward me as if I were her rapist,” he says. “And as if she’s acting on behalf of womankind.”

Which, in fact, is the definition of a movement — that Muth and Collett stand behind a cause. Muth in particular has her critics, plenty of observers who think she’s riding the Leach story largely as a political gambit. But whatever her motivation, there’s no question she’s fully invested, and her caucus will ignore her at its peril. That includes Jay Costa, up for reelection next year in Allegheny County. Muth laughs about how she, a 35-year-old freshman senator from the other end of the state, could have that sort of clout, but it’s a laugh that makes clear that taking on Costa isn’t a new idea.

Meanwhile, Daylin Leach is still standing firm.

At the end of a long conversation in his office in Harrisburg, he says of his accusers, “They are just dreadful people — they say in Puke Fuck, if we take down Leach, every male senator is going to have to bow down to us. Is that a good state of affairs? No. Someone has to stand up to these people. … Al Franken just resigned.”

I wonder if Franken has been destroyed by what happened.

“That’s a great question,” Leach says. “I’d love to know the answer.”

Leach is livid that Eckert was directed by the Democratic caucus to do more work, seeing it as a redo to come back with different findings. Leach threatened to make Eckert’s preliminary report public and claims that minority leader Costa said he’d publicly call for Leach’s resignation if he did.

Was Leach going to back down now? He made the PowerPoint of the Eckert report public, saying, in a strange choice of wording that echoes the president he despises, that he’d been “exonerated.” Costa then publicly called for Leach’s resignation. And everyone went home for the summer.

This month, they all return.

Published as “The Senator Says He’s Not A Rapist” in the September 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.