We’re All Getting Screwed by Fees, Pretty Much All the Time

Inside the infuriating world of the hidden fee economy.

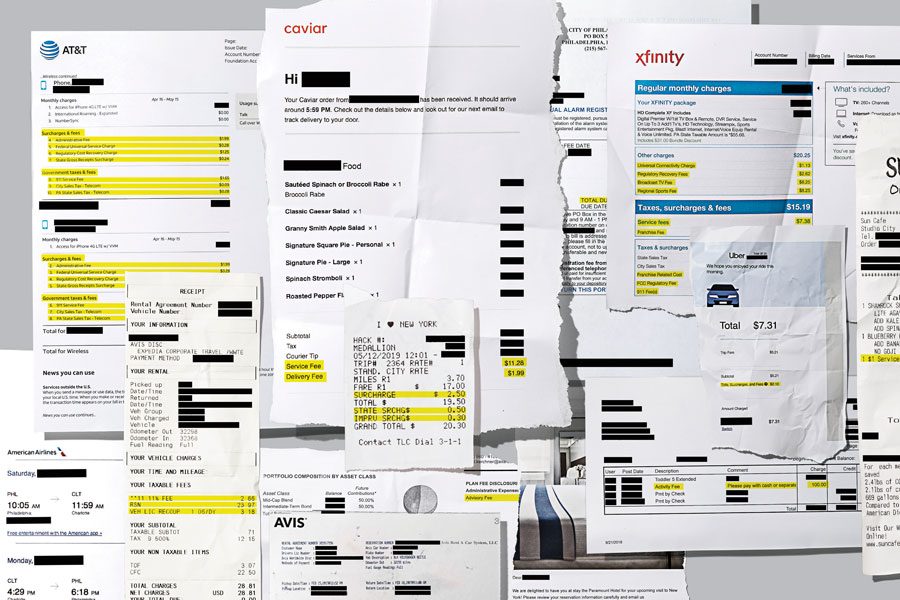

Hidden fees are everywhere. Photograph by Claudia Gavin.

There’s something perversely satisfying about learning that someone who screwed you over is, in turn, getting screwed.

That was my first thought when I read recently that bankers — never ones to shy away from soaking people with all manner of fees — were incensed that the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq had been steadily inching up the fees they charge banks for access to data. Bank execs claimed they were paying 10 times more in 2018 than they had in 2010 for the same vital info. The exchanges, bank execs complained to the Wall Street Journal, “don’t disclose profit margin for these kinds of services” and “have monopoly pricing power.”

I had to wonder: Did any of the bankers who gave quotes to the Journal stop to ponder the irony? Lack of transparency? Egregious gouging? I laughed and told myself it wasn’t going to be such a bad day after all.

There are a few universal facts of life: We all die. We all poop. And we’re all getting screwed by fees, pretty much all the time. According to a survey released in May by Consumer Reports, 85 percent of Americans have encountered a hidden fee over the past two years — and two-thirds say they’re getting hit with more surprise charges than they did five years ago.

When I started telling people a few months ago that I was writing about fees, everyone had a story to share, and I watched as their voices rose a few octaves, their arms flailed, and their faces contorted. (Comcast came up a lot. So did the airlines.) Googling “fees outrage” pulls up hundreds of posts about people losing their minds (and, in some cases, filing lawsuits) over fees. “When you feel powerless and are forced to do something, you get outraged,” says Alice Moon, an assistant professor of operations, information and decisions at Wharton. But there are other emotions associated with fees, too, like helplessness, guilt, and a sense of injustice.

If you’ve felt any of those feelings when confronted with a fee — i.e., if you’re alive — take a deep breath, because your blood pressure is only going to go up from here. When you take a closer look — when you really start to examine your bills, your receipts, and what you’re agreeing to when you click “buy now” — you realize it’s not just in-your-face banking and baggage fees. We’re actually being assaulted with a million tiny tariffs — a few dollars here, a few dollars there — all day long. When I was little, my brother used to sneak up next to me, quietly put his finger next to my cheek, then call my name. That’s what fees feel like today — every time I turn my head, I’m being unexpectedly poked.

I tracked the fees I paid over the course of a few months just to see how bad the situation really is. I combed through paid bills, email receipts, paper receipts, and bank and credit-card statements. I found fees on my AT&T cell-phone bill and my Xfinity bill; an annual $100 activity fee for my daughter’s daycare in Queen Village (which is already a good chunk of change); a surcharge on tickets for a show at the Arden; a bonkers Uber surging fee from a day when it was raining (I could have taken a taxi, but of course, that has a fuel surcharge); the fee for being on my husband’s health insurance because I have the option of being on my own; and some Caviar fees from Santucci’s and Bing Bing (those bills included both a delivery fee and a service fee, and I had to tip the driver). There’s more! There was the annual $50 fee I have to pay to the City of Philadelphia for having a security system on my own house (are you effing kidding me?); something called a “small cart fee” on Postmates (that’s on top of the service fee and $5.99 delivery fee); the $200-plus we paid in admin fees for leasing a car from a dealership in Cherry Hill; and a $3.95 fee on my water bill, not because I was late with my payment, but because I used a credit card. I could actually go on, but for the sake of my health, as well as not punching a hole through my wall, I’ll stop. Grand total: somewhere in the thousands of dollars per year.

When you have some time to kill, examine your bills and read all that fine print. You’ll see the fees, too, although they might be disguised with noms de plume like “surcharge,” “processing,” “handling” and “toll.” Economists — and CEOs, I would imagine — refer to them as “partitioned pricing,” a phrase that’s become the main character in many academic papers and studies. Which makes sense, because we’re officially living in a fee economy.

The economic downturn demanded that businesses come up with creative ways to bring in more revenue without raising prices, but like the “temporary” tollbooths set up on the Garden State Parkway in the 1950s, fees are here to stay.

While partitioned pricing has existed for centuries, it’s just recently grown “more pervasive and complex,” according to an article written by professors from NYU and Columbia and published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology in 2016. The 2008 recession is partially to blame for this: The economic downturn demanded that businesses come up with creative ways to bring in more revenue without raising prices, which would have been unpalatable to newly cash-strapped Americans. But like the “temporary” tollbooths set up on the Garden State Parkway in the 1950s, fees are here to stay. In fact, partitioned pricing has emerged as a reliable revenue stream, or a complete business model, for more businesses and governments than ever before. And in a trickle-down, pass-the-buck kind of way, guess whom it hurts the most? Yup, you and me.

Comedian Sebastian Maniscalco has a bit about airports in his 2014 special Aren’t You Embarrassed? “Now, the check-in process at the airport — they don’t even want to look at you. Head down, no smile, nothing,” he says, all agitated and hopping around the stage. “The only time they get happy is when the bag goes over the weight allowance. They love telling you you are gonna owe extra on this bag.” He goes on: “She’s like, ‘Oooohhhh, I’m soooorrry, your bag is two pounds over.” (Live audience roars in laughter, then probably cries a little inside.)

Jokes aside, baggage fees were a tipping point — the BC/AD benchmark in the historical timeline of inane consumer fees. Major airline carriers in this country began charging small fees for second checked bags in 2002. But in 2008, two noteworthy factors changed the fees game forever: Fuel prices soared to near-all-time highs, and the economy tanked. In May of that year, American Airlines boldly announced it would start charging passengers $15 to check their first bag on all domestic flights. “Our company and industry simply cannot afford to sit by hoping for industry and market conditions to improve,” American’s chief executive, Gerard Arpey, told shareholders. “Analysts said that they expected other carriers would watch passenger reaction to American’s decision and were likely to institute their own first-bag charges,” the New York Times wrote at the time.

Prescient. Today, most major national carriers charge for checked bags — and budget carriers like Frontier and Allegiant charge for checked bags and carry-ons. But while fuel prices have come way down since then, airline surcharges and fees have only gone up. American now charges $30 per bag, per flight leg for customers flying coach. Meanwhile, Ireland’s Ryanair has a baggage fee and an airport check-in fee, and it’s toyed — no joke — with adding a facility fee. (See? They know we all have to poop.) Here’s why baggage fees are sticking around: American Airlines made more than $1 billion from them in 2017 alone.

You can bet that other captains of industry have been watching. As when Starbucks rolled out $4 lattes and Lululemon unleashed $90 yoga pants into the universe, there’s no turning back. Joydeep Srivastava, a professor of marketing at Temple’s Fox School of Business, explains this concept to me one May afternoon. “Once things become part-and-parcel of the norm, people tend to buy into it,” he says. “The whole notion of norm is very dynamic. What the norm is now is not the norm tomorrow. To some people, paying $30 a night for parking is outrageous and always will be. But to most people, who see that every hotel is charging around $30 … defenses are lowered, and you know there’s no getting out of it.” In essence, the shock factor dissipates. Wharton’s Moon calls it our “reference point.” Once it’s been adjusted, we feel neutral, no matter how absurd a price may be.

Of course, American Airlines didn’t invent the concept of fees. They took it from the playbook of banks and governments, which have used partitioned pricing since, I don’t know, feudal days? For banks, at least, one could argue that the original conceit was sensible: If you withdrew more money than you had in your account, you had to pay a penalty. (Americans paid $34.3 billion in overdraft fees in 2017.) Similarly, governments and government-adjacent organizations (like Philly’s Center City District) have long used fees to pay for goods and services that fall outside an agreed-upon state or city budget. In the case of the CCD, businesses and residents fork over an annual fee in return for clean sidewalks, working streetlights and, I guess, Center City Sips.

But many of the fees we now encounter on the regular aren’t so transparent and, in fact, spring from a very different place: They’re simply a way for businesses to generate new revenue or deal with rising costs without raising their base prices.

There are plenty of examples of flagrant deception in this new world, like the recent trend of pool-and-palm-less city hotels implementing “resort fees” to pay for stuff like breakfast buffets and high-speed internet. (Lawsuits have ensued.) Other fees come not from greed, but from the government. To wit: In order to ensure that people living in low-income and rural areas have affordable access to broadband, the FCC created the Universal Service fund, which is paid for by telecom operators. Comcast passes that cost on to consumers; you’ll see it labeled as the “Universal Connectivity Charge” on your Xfinity bill. Mine is $1.13 a month. (A spokesperson for Comcast told me the pass-along is permitted by the government and is industry-standard. You’ll see similar charges from providers like Verizon.)

Now, if you’re saying to yourself, But isn’t that just the cost of doing business? — well, yes. It’s clearly an expense Comcast could choose to eat. But it’s just one of many fees the telecom giant charges customers on top of the regular cost of service. Some are government-created; others are to offset Comcast’s own rising costs; still others are just plain head-scratching. Altogether, I pay more than $20 a month in fees to Comcast for voice, internet and cable access.

Comcast can pass surcharges on to consumers without much pushback. But that’s not true of all businesses — especially smaller operations that can’t raise prices and tack on fees for fear of losing customers to the competition. In 2017, the Washington, D.C., outpost of seafood restaurant Oceanaire stuck a three percent service fee on the bottom of its checks, explaining this was due to the “rising costs of doing business in this location, including costs associated with higher minimum wage rates. … ” After public outrage, the fee was removed. But the Washington Post reports that Los Angeles restaurant AOC and a group of eateries in Minnesota have also added surcharges, to help defray the rising costs of employee health care.

(Blood-pressure-check time: You okay?)

Fees also come about because businesses are getting walloped by other businesses. I’m calling this the Food Chain — Fee Edition. Let’s use Philadelphia taxis as an example. A customer gets in a cab, and the meter starts running. When the ride is over — maybe it’s $12, plus tip, to get from Rittenhouse to Fishtown — a driver starts mentally backing out his costs: Gas can be expensive; credit-card transactions cost him an insane five percent; drivers typically have to pay something to the medallion owner to lease the car; medallion owners pay one percent of all fares to the PPA. It’s no wonder some drivers feel like foxes getting hunted down by a pride of lions.

But the fox is hungry, too, which is why it goes searching for a delicious rabbit. Who’s the rabbit? We are. Taxis pass on as many fees to riders as they can. If you’re being picked up at the airport, you’ll pay a $1.50 PHL fee (which the airport charges the drivers to cover, it says, operational costs related to managing taxi stands and such), and you’ll also have to pay a $1-per-person surcharge if there’s more than one adult rider. And since 2012, all rides have had a fuel surcharge, which fluctuates based on the cost of gas (another example of a fee that was instituted to offset the high cost of fuel that isn’t ever coming off).

The drivers have discussed adding even more surcharges, because beyond everything they have to pay out, they also face steep competition from Uber and Lyft. “We are fighting for our economic lives right now,” Ronald Blount, president of the Unified Taxi Workers Alliance of Pennsylvania, told me in early May. “We don’t want to add anything else to this meter. People already believe taxicabs are high compared to some others — sometimes it’s true, sometimes it isn’t. But if it goes out publicly that the price is going up? Riders aren’t going to like that.”

There’s one more reason why fees have become so prolific, and that is — shocker — the internet. The way people search before they buy has sparked a pricing war, and he who has the lowest advertised price often snags the click. That’s why I thought I was getting $199 Lion King tickets on Broadway.com, only to find out (well past the arduous seat-selection process) that the site was charging a $75 per ticket fee. This is called drip pricing, and it’s something that hotels, airlines, retailers, etc., routinely employ these days. “The fact is, comparing prices involves going to specific websites, entering in all the info, and then you see the fees,” says Srivastava. “Well, the deeper you get into the process, the sale is closed out, more often than not.” (Not for this lady — I passed on those show tickets.)

In almost no everyday life situation are consumers confronted with fees more than when they travel. I recently tried to transfer some American Airline miles to my husband and discovered it was going to cost $300 in fees just to move my own miles. On my recent trip to L.A. — where renting a car is as essential as having cool shades — Avis charged me a facility fee (because, as is explained on their site, LAX charges them to operate there) and an energy recovery fee “to help recover the escalating energy costs related to our business operations. … ” I decided not to take the optional e-toll reader, because whether I used it or not, I was going to have to pay $3.50 a day for it. (Also on this trip, I ordered two smoothies at a takeout counter in Studio City and, after looking at the receipt, saw a $1 surcharge that didn’t have an explanation. Really, someone should be paying me to drink goji berries.)

But the most atrocious travel example I can offer up is when we flew Frontier Airlines to visit family in Florida last Christmas. When we went to check in, the airline had given us four separate seats. While I would have loved nothing more than to stick my three-year-old in seat 27C between two strangers while I read a book and sipped a cocktail four rows up, this wasn’t going to work. The woman at the ticket counter said she couldn’t help, and that next time, we should pay the fee to reserve our seats together. Isn’t reserving a seat exactly what my ticket price bought me? Our family vacation started off with me begging people to switch seats so that my toddler and first-grader didn’t have to sit alone. (Shout-out to the sweet mom and son in Eagles shirts who agreed to help us out.)

But for every instance of fee-induced rage, there are 10 times as many people who have come to feel absolutely nothing. Sure, it’s because of the normalization/desensitization thing. But it’s also because sometimes, paying fees gives us something that’s valued even more than money these days: time. A 2017 New York Times article titled “Want to Be Happy? Buy More Takeout and Hire a Maid, Study Suggests” reported that people who spent cash on services that save time — ordering delivery dinner, taking a cab, having someone else run their errands — were, overall, happier. “And it didn’t matter if they were rich or poor: People benefited from buying time regardless of where they fell on the income spectrum,” the story reported.

Some people, though, view services as guilty indulgences. A friend told me she feels bad that the delivery fees she pays on dinner are sometimes more than the actual cost of the food. “Guilt comes in when you have to justify the cost to yourself or someone else,” says Srivastava. “And if you start to do something on a regular basis.” The truth, though: Once you go Caviar delivery, you never go back.

Corporations are all over the consumer-psychology side of this equation. Some brands, like Southwest Airlines, take a Michelle Obama “When they go low, we go high” approach. Southwest has higher base fares (in many cases, barely higher) but doesn’t charge baggage or change fees. The company is banking on this differentiator building brand loyalty.

Local tech company GoPuff, which delivers convenience-store goods with a flat $1.95 fee, believes strongly that transparency and fairness bring repeat customers. “Our customers are vocal, which has enabled us to understand that they are price-conscious with delivery fees,” says Daniel Folkman, vice president of business development. Of course, since GoPuff sells goods rather than just providing a service, like UberEats or Caviar, costs can get built into the products. A bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos runs $2.49 with GoPuff but only $1.89 at Target.

But what GoPuff has tapped into here is, perhaps, a fourth universal life truth: People despise shipping fees. “There’s literature that says a promotion with free shipping is more effective than a discount for the same price,” says Moon. Even, she goes on to explain, if it really doesn’t mean more money off in the end.

It’s also why companies like Amazon have been successful at selling annual memberships that get consumers free shipping for the year. “It might not actually make economic sense, but Amazon has done a nice job of coupling it with videos and all these other things, so you feel like you’re getting value,” says Srivastava. And Jeff Bezos is no dummy: When you’ve paid out a membership fee and perceive that you’re getting free shipping, you’re more likely to return to that same site for subsequent purchases.

There’s another, more insidious emotional factor that plays into what we accept and won’t accept when it comes to fees: the fact that we’ve become a nearly cashless society. “Research has shown that people think of money — particularly when they’re using Venmo or PayPal — almost like Monopoly money,” says Srivastava. “You don’t have the same level of control or the pain of writing a check. That makes people less sensitive to the added fees.” Big purchases have long been cashless (mortgages, car payments, school tuition), but as we start to wave our phones or hit “one-click buy” for smaller purchases more often, we’ve lost the tactile experience of taking actual bills out of our actual pocket and really thinking about what we’re going to fork over our hard-earned money for. When I was growing up — way before the digital age — we would rag on my dad about this. The very generous man wouldn’t negotiate over a big credit-card purchase, like a new TV at Best Buy, but would haggle the hell out of a guy selling a $2 light-up yo-yo on the street.

In 2013, a Minnesota man named Corey Statham was arrested for disorderly conduct. He had $46 on him at the time. He was charged a $25 “booking fee” by the local municipality for being arrested. Charges were dropped, and Statham was released two days later, but he was told that to get the booking fee refunded, he’d have to prove he was innocent. (Seriously.) The county eventually returned $21 of the fee but did so with a debit card; when Statham went to withdraw his money, he got hit with $7.25 in bank fees. Eventually, he sued; his attorney wrote that booking fees had been imposed because local governments were cash-strapped and needed a way to “bridge their budgetary gaps.” He also argued that the fees were motivation to arrest people. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016, but the ruling of a lower court was allowed to stand. Statham lost. Fees won.

When you follow the fee food chain and dig into who gets hurt the most, you arrive at the people who are in the most challenging financial situations. In his 2018 book Land of the Fee, University of Missouri professor of history, black studies and public affairs Devin Fergus argues that the fee economy is another conspicuous example of how middle- and lower-income Americans get screwed. “American capitalism’s most celebrated period of success corresponded with the period, roughly from 1940 to the 1970s, when government was biggest and imposed the highest and most comprehensive regulatory standards on big business,” writes Fergus. “Since then, financial deregulation has coincided with a deteriorating economic situation for working and middle-class Americans.” So: The government not only causes some of these situations, but also fails to regulate how businesses are recouping their costs. As the Comcast spokeswoman repeatedly informed me, the cable giant is allowed to pass along all the fees it does, essentially making some of the fees passed along into a regressive tax. It’s another example of modern-day corporations putting stockholders ahead of everyone else.

Feeling mad yet, or just deflated and helpless? Take some solace in the fact that advocacy groups exist. Consumer Reports magazine has taken on this cause with a vengeance. They’ve conducted research and written dozens of articles that explain the fees that come along with things like car purchases, and they offer advice on how to negotiate cable bills. Their advocacy arm, Consumer Union, has created a digital forum called “What the Fee” where people share horror stories and offer tips. They also put out a survey in 2018 asking which industries and companies seem to have the most unfair pricing structures. More than 115,000 people responded, and around 25 percent named Comcast as their number one source of fee-related ire. (Tell us something we don’t know.) Consumer Union also started a petition calling for cable providers to eliminate add-on fees and be more on the straight-and-narrow with customers. There are currently more than 140,000 signatures.

Now, despite all of this — despite all of the absurd fees I realized I encounter regularly — there was one that came up in my research that was truly jaw-dropping. It’s personal, sure, but also terrifying, because it has whiffs of totalitarianism. In 2018, the New York Times reported that without any announcement or discussion, the Belgian government started charging journalists a fee to cover EU and NATO meetings. Once called out, their defense was that there’s an increased demand for background checks following terrorist attacks and that the fees are similar to those in other industries like finance and health care. Tom Weingaertner, president of the International Press Association in Brussels, protested that this was “a restriction of press freedom and sets a very big precedent.” Thank goodness President Trump doesn’t believe anything he reads in the Times.

Published as “Death by a Thousand Fees” in the July 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.